Allopatric speciation

Allopatric speciation (from the ancient Greek allos, "other" + Greek patris, "fatherland") or geographic speciation is speciation that occurs when biological populations of the same species become vicariant, or isolated from each other to an extent that prevents or interferes with genetic interchange. This can be the result of population dispersal leading to emigration, or by geographical changes such as mountain formation, island formation, or large scale human activities (for example agricultural and civil engineering developments). The vicariant populations then undergo genotypic or phenotypic divergence as: (a) they become subjected to different selective pressures, (b) they independently undergo genetic drift, and (c) different mutations arise in the gene pools of the populations.[1]

The separate populations over time may evolve distinctly different characteristics. If the geographical barriers are later removed, members of the two populations may be unable to successfully mate with each other, at which point, the genetically isolated groups have emerged as different species. Allopatric isolation is a key factor in speciation and a common process by which new species arise.[2] Adaptive radiation, as observed by Charles Darwin in Galapagos finches, is a consequence of allopatric speciation among island populations.

Isolating mechanisms

Allopatric speciation may occur when a species is subdivided into geographically isolated populations. Such separation commonly is referred to as vicariance. Allopatric and allopatry are terms from biogeography, referring to organisms whose ranges are entirely separate such that they do not occur in any one place together. If these organisms are closely related (e.g. sister species), such a distribution is usually the result of allopatric speciation. Separation may be attributed to either geological processes or population dispersal.

Geological processes

Geological processes can fragment a population through such events as emergence of mountain ranges, canyon formation, glacial processes, the formation or destruction of land bridges, or the subsidence of large bodies of water. On a global scale, plate tectonics is a major geological factor that can lead to the separation of populations to result in the distribution of species.

Approximately 50,000 years ago, the Death Valley region of the western United States had a rainy climate which produced an interconnecting system of freshwater rivers and lakes. Climatic changes resulted in a drying trend that has continued for the last 10,000 years. As the lakes and rivers shrank, fish populations became geologically isolated. The few remaining (separated) springs are currently home to a variety of fish, many sharing a close common ancestor; yet each has uniquely adapted to its own particular pool.

The extent to which a geological barrier can effectively isolate a population correlates to the mobility of the organism or its offspring. For example, physical barriers such as canyons may effectively block migration and dispersal of small mammals; however, they have little impact on flying birds or wind-borne seeds.[3]

Population dispersal

Population dispersal is used to describe migratory events, either in the form of range expansion (natural movement away from parents) or jump dispersal (crossing of barriers), which may lead to genetic isolation. If the smaller population fragment becomes genetically isolated from the parental group, it may be subjected to its own unique mutations, selection forces, and genetic drift effects; thus, it will follow its own evolutionary pathway. Migrations or accidental relocations (such as birds being blown off course) may lead to population fragments; whereby groups merely become separated by distance. Once gene flow between the two groups is disrupted, speciation becomes a possibility.

In peripheral populations

When populations become genetically isolated, heritable variations may accumulate so that they become different from the parental population. Given sufficient time, these variations may lead to reproductive isolation.

Portions of a populations that exist along the edges of the parent population's geographic territory have higher likelihood of developing reproductive isolation. Such peripheral populations are likely to possess genes that are different from the parental population. After isolation, the founding population is less likely to represent the gene pool of the parent population. In addition, peripheral isolates are likely to represent a small number of individuals, meaning their gene pool is more susceptible to the effects of genetic drift (random chance). Furthermore, it is likely that the peripheral population will inhabit an environment different from its ancestral gene pool, likely causing it to be subjected to different selective pressures as it colonizes new areas. The outer periphery of a population's habitat tends to be extreme; hence, the reason range expansion is kept in check. For most peripheral isolates, it is more likely that they die off rather than survive and speciate.

Genesis of reproductive barriers

Adaptive divergence may occur when a population becomes geographically divided: followed by an accumulation of genetic differences as they adapt to their own unique environments. Reproductive barriers do not evolve as a consequence of external forces that drive populations toward speciation. Rather, the evolution of reproductive isolation, leading to speciation, is generally thought to be an incidental by-product of genetic divergence, particularly adaptive changes that evolve through natural selection in response to different environmental conditions in separate geographic areas.[4]

The Biological Species Concept, proposed by Ernst Mayr, in 1942, emphasizes reproductive isolation as the basis of defining a species.[5] The definition states: "A species is defined as a population or group of populations whose members have the potential to interbreed with one another in nature and to produce viable offspring, but cannot produce viable, fertile offspring with members of other species." Mayr, a proponent of allopatric speciation, hypothesized that adaptive genetic changes that accumulate between allopatric populations cause negative epistasis in hybrids, resulting in sterility of the offspring.

If there is considerable genetic and phenotypic change without the loss of the capacity for interbreeding, then such hybridization is simply prevented by the geographical separation of populations. In this case the populations are normally regarded as subspecies.

The frequency of other types of speciation, such as sympatric speciation, parapatric speciation, and heteropatric speciation, is debated. Proponents of peripatric speciation contend that small population size in the peripheral isolate (sometimes referred to as a "splinter population") increases genetic drift, which can be a more powerful force than natural selection in small populations. It deconstructs complex genotypes, allowing the creation of novel gene combinations. Both forms need not be mutually exclusive. In practice, passive isolation or fragmentation as well as active dispersal seem to play a role in many cases of speciation.

Alternative modes of speciation

Sympatric speciation represents an alternative method of speciation that does not require physical separation; instead speciation occurs within a population sharing the same geographic boundaries.[6] For example, the development of polyploidy in plant species can lead to a new species arising within the geographic range of its parent population.

In parapatric speciation there is no physical barrier to gene exchange within the population. Instead, the population is continuous; however, mating is not random. Individuals mate with their closest neighbors rather than with individuals in a more distant location. Divergence may occur as a consequence of both reduced gene flow and natural selection, imposed by the large distance between individuals within a population's habitat.[7]

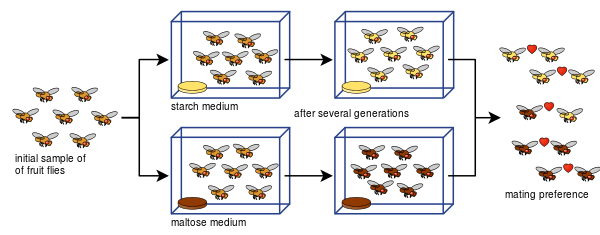

Behavioural changes can also create isolation that leads to speciation. Also called ethological Isolation, the phenomena can be seen in birds with different call patterns, lightning bugs with different flash patterns and monkeys with facial markings. All are selective in which individuals they breed with to the point of isolation. .[8]

Allopatric speciation is thought to be the dominant mode of speciation.[9]

Examples

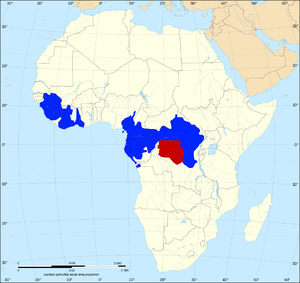

The African elephant has always been regarded as a single species but, because of morphological and DNA differences, some scientists classify them into three subspecies. Researchers at the University of California, San Diego have argued that divergence due to geographical isolation has gone further, and the elephants of West Africa should be regarded as a separate species from both the savanna elephants of Central, Eastern and Southern Africa, and the forest elephants of Central Africa. A similar situation exists with the Asian elephant, which has four distinct living sub-species.[10] The definition of what causes two organisms to be different species is quite ambiguous but the simplest definition is that if the two organisms cannot interbreed they are different species.

Other cases arise where two populations that are quite distinct morphologically, and are native to different continents, have been classified as different species; but when members of one species are introduced into the other's range, they are found to interbreed freely, showing that they were in fact only geographically isolated subspecies. This was found to be the case when the mallard was introduced into New Zealand and interbred freely with the native grey duck, which had been classified as a separate species. It is controversial whether its specific status can now be retained. Mallards interbreed similarly and aggressively with the southern African yellow-billed duck.

See also

- Disjunct distribution

- Habitat fragmentation

- Sympatric

- Ecological speciation

- River barrier hypothesis

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Hoskin 2005, p. 1353

- ↑ Lande 1980, p. 463

- ↑ Campbell 2002, p. 469

- ↑ Gavrilets 1998, p. 1483

- ↑ Mayr 1970, p. 13

- ↑ Rivas 1964, p. 42

- ↑ Campbell 2002, p. 473

- ↑ Comba, Livio (1999). "Patch use by bumblebees (Hymenoptera Apidae): temperature, wind, flower density and traplining". Ethology Ecology & Evolution. 11 (3): 243–264. doi:10.1080/08927014.1999.9522826. Retrieved 2015. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Futuyma 1980, p. 254

- ↑ Fickel 2007

Bibliography

- Campbell, Neil; Reece, Jane (2002). Biology (6th ed.). Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-6624-5.

- Fickel, Joerns; Lieckfeldt, Dietmar; Ratanakorn, Parntep; Pitra, Christian (2007). "Distribution of haplotypes and microsatellite alleles among Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) in Thailand" (PDF). European Journal of Wildlife Research. 53 (4): 298–303. doi:10.1007/s10344-007-0099-x. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- Futuyma, Douglas J.; Mayer, Gregory C. (1980). "Non-Allopatric Speciation in Animals". Systematic Zoology. 29 (3): 254. doi:10.2307/2412661. JSTOR 2412661.

- Gavrilets, Sergey; Li, Hai; Vose, Michael (1998). "Rapid parapatric speciation on holey adaptive landscapes" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 265 (1405): 1483–1489. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0461. PMC 1689320

. PMID 9744103.

. PMID 9744103. - Hoskin, Conrad J; Higgie, Megan; McDonald, Keith R; Moritz, Craig (2005). "Reinforcement drives rapid allopatric speciation". Nature. 437 (7063): 1353–1356. doi:10.1038/nature04004. PMID 16251964.

- Lande, Russell (1980). "Genetic Variation and Phenotypic Evolution During Allopatric Speciation". The American Naturalist. 116 (4): 463–479. doi:10.1086/283642. JSTOR 2460440.

- Mayr, Ernst (1970). Populations, Species, and Evolution. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-69013-3. Retrieved 2010-12-11.

- Rivas, Luis R (1964). "A Reinterpretation of the Concepts "Sympatric" and "Allopatric" with Proposal of the Additional Terms "Syntopic" and "Allotopic"". Systematic Biology. 13(1-4): 42–43. doi:10.2307/sysbio/13.1-4.42.