Systematics

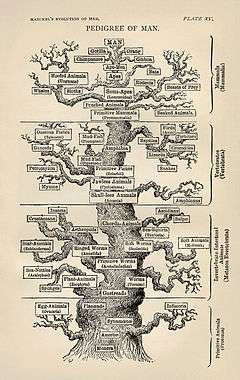

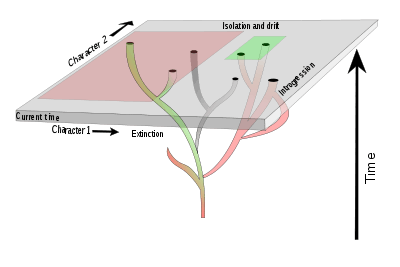

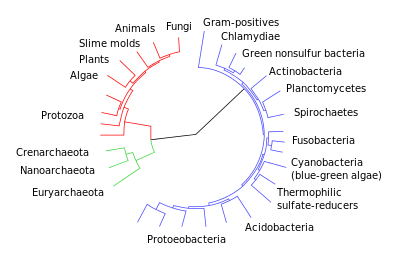

Biological systematics is the study of the diversification of living forms, both past and present, and the relationships among living things through time. Relationships are visualized as evolutionary trees (synonyms: cladograms, phylogenetic trees, phylogenies). Phylogenies have two components, branching order (showing group relationships) and branch length (showing amount of evolution). Phylogenetic trees of species and higher taxa are used to study the evolution of traits (e.g., anatomical or molecular characteristics) and the distribution of organisms (biogeography). Systematics, in other words, is used to understand the evolutionary history of life on Earth.

Definition and relation with taxonomy

John Lindley provided an early definition of systematics in 1830, although he wrote of "systematic botany" rather than using the term "systematics".[1]

In 1970 Michener et al. defined "systematic biology" and "taxonomy" (terms that are often confused and used interchangeably) in relationship to one another as follows:[2]

Systematic biology (hereafter called simply systematics) is the field that (a) provides scientific names for organisms, (b) describes them, (c) preserves collections of them, (d) provides classifications for the organisms, keys for their identification, and data on their distributions, (e) investigates their evolutionary histories, and (f) considers their environmental adaptations. This is a field with a long history that in recent years has experienced a notable renaissance, principally with respect to theoretical content. Part of the theoretical material has to do with evolutionary areas (topics e and f above), the rest relates especially to the problem of classification. Taxonomy is that part of Systematics concerned with topics (a) to (d) above.

Taxonomy, systematic biology, systematics, biosystematics, scientific classification, biological classification, phylogenetics: At various times in history, all these words have had overlapping meanings — sometimes the same, sometimes slightly different, but always overlapping and related. However, in modern usage, they can all be considered synonyms of each other.

For example, Webster's 9th New Collegiate Dictionary of 1987 treats "classification", "taxonomy", and "systematics" as synonymous. According to this work the terms originated in 1790, c. 1828, and in 1888 respectively. Some claim systematics alone deals specifically with relationships through time, and that it can be synonymous with phylogenetics, broadly dealing with the inferred hierarchy of organisms, which means it would be as subset of taxonomy as it is sometimes regarded, but the inverse is claimed by others.

Europeans tend to use the terms "systematics" and "biosystematics" for the field of the study of biodiversity as a whole, whereas North Americans tend to use "taxonomy" more frequently.[3] However, taxonomy, and in particular alpha taxonomy, is more specifically the identification, description, and naming (i.e. nomenclature) of organisms,[4] while "classification" focuses on placing organisms within hierarchical groups that show their relationships to other organisms. All of these biological disciplines can deal both with extinct and with extant organisms.

Systematics uses taxonomy as a primary tool in understanding, as nothing about an organism's relationships with other living things can be understood without it first being properly studied and described in sufficient detail to identify and classify it correctly. Scientific classifications are aids in recording and reporting information to other scientists and to laymen. The systematist, a scientist who specializes in systematics, must, therefore, be able to use existing classification systems, or at least know them well enough to skilfully justify not using them.

Phenetics was an attempt to determine the relationships of organisms through a measure of overall similarity, making no distinction between plesiomorphies (shared ancestral traits) and apomorphies (derived traits). From the late-20th century onwards, it was superseded by cladistics, which rejects plesiomorphies in attempting to resolve the phylogeny of Earth's various organisms through time. Today's systematists generally make extensive use of molecular biology and of computer programs to study organisms.

Taxonomic characters

Taxonomic characters are the taxonomic attributes that can be used to provide the evidence from which relationships (the phylogeny) between taxa are inferred. [5] Kinds of taxonomic characters:[6]

|

|

See also

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

|

History of evolutionary theory |

|

Fields and applications

|

|

- Biological classification

- Cladistics - a methodology in systematics

- Evolutionary systematics - a school of systematics

- Global biodiversity

- Phenetics - a methodology in systematics that does not infer phylogeny

- Phylogeny - the historical relationships between lineages of organism

- 16S ribosomal RNA - an intensively studied nucleic acid that has been useful in phylogenetics

- Phylogenetic comparative methods - use of evolutionary trees in other studies, such as biodiversity, comparative biology. adaptation, or evolutionary mechanisms

- Scientific classification and Taxonomy - the result of research in systematics

References

Notes

- ↑ Wilkins, J. S. What is systematics and what is taxonomy?. Available on http://evolvingthoughts.net

- ↑ Michener, Charles D., John O. Corliss, Richard S. Cowan, Peter H. Raven, Curtis W. Sabrosky, Donald S. Squires, and G. W. Wharton (1970). Systematics In Support of Biological Research. Division of Biology and Agriculture, National Research Council. Washington, D.C. 25 pp.

- ↑ Brusca, R. C., & Brusca, G. J. (2003). Invertebrates (2nd ed.). Sunderland, Mass. : Sinauer Associates, p. 27

- ↑ Fortey, Richard (2008), Dry Store Room No. 1: The Secret Life of the Natural History Museum, London: Harper Perennial, ISBN 978-0-00-720989-7

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst (1991). Principles of Systematic Zoology. New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 159.

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst (1991), p. 162.

Further Reading

- Schuh, Randall T. and Andrew V. Z. Brower. 2009. Biological Systematics: Principles and Applications, 2nd edn. ISBN 978-0-8014-4799-0

- Simpson, Michael G. 2005. Plant Systematics. ISBN 978-0-12-644460-5