Great Smoky Mountains National Park

| Great Smoky Mountains National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

Entrance to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, from Cherokee, North Carolina | |

| |

| Location | Swain & Haywood counties in North Carolina; Sevier, Blount, & Cocke counties in Tennessee, U.S. |

| Nearest city | Cherokee, North Carolina and Gatlinburg, Tennessee |

| Coordinates | 35°41′N 83°32′W / 35.683°N 83.533°WCoordinates: 35°41′N 83°32′W / 35.683°N 83.533°W |

| Area | 522,419 acres (816.280 sq mi; 211,415 ha; 2,114.15 km2)[1] |

| Visitors | 10,712,674 (in 2015)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Great Smoky Mountains National Park |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | VII, VIII, IX, X |

| Designated | 1983 (7th session) |

| Reference no. | 259 |

| State Party |

|

| Region | North America |

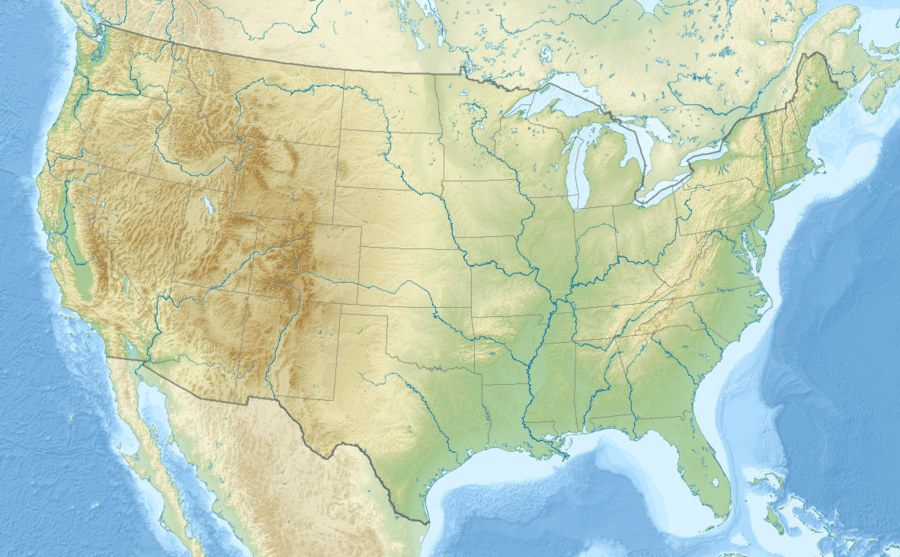

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is a United States National Park and UNESCO World Heritage Site that straddles the ridgeline of the Great Smoky Mountains, part of the Blue Ridge Mountains, which are a division of the larger Appalachian Mountain chain. The border between Tennessee and North Carolina runs northeast to southwest through the centerline of the park. It is the most visited national park in the United States.[3] On its route from Maine to Georgia, the Appalachian Trail also passes through the center of the park. The park was chartered by the United States Congress in 1934 and officially dedicated by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1940.[4] It encompasses 522,419 acres (816.28 sq mi; 211,415.47 ha; 2,114.15 km2),[1] making it one of the largest protected areas in the eastern United States. The main park entrances are located along U.S. Highway 441 (Newfound Gap Road) at the towns of Gatlinburg, Tennessee, and Cherokee, North Carolina. It was the first national park whose land and other costs were paid for in part with federal funds; previous parks were funded wholly with state money or private funds.[5] Due to the 2016 Great Smoky Mountains wildfires, the Park was under evacuation orders, along with some towns and cities located nearby.

History

Before the arrival of European settlers, the region was part of the homeland of the Cherokees. Frontiers people began settling the land in the 18th and early 19th century. In 1830 President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, beginning the process that eventually resulted in the forced removal of all Indian tribes east of the Mississippi River to what is now Oklahoma. Many of the Cherokee left, but some, led by renegade warrior Tsali, hid out in the area that is now the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Some of their descendants now live in the Qualla Boundary to the south of the park.

As white settlers arrived, logging grew as a major industry in the mountains, and a rail line, the Little River Railroad, was constructed in the late-19th Century to haul timber out of the remote regions of the area. Cut-and-run-style clearcutting was destroying the natural beauty of the area, so visitors and locals banded together to raise money for preservation of the land. The U.S. National Park Service wanted a park in the eastern United States, but did not have much money to establish one. Though Congress had authorized the park in 1926, there was no nucleus of federally owned land around which to build a park. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., contributed $5 million, the U.S. government added $2 million, and private citizens from Tennessee and North Carolina pitched in to assemble the land for the park, piece by piece. Slowly, mountain homesteaders, miners, and loggers were evicted from the land. Farms and timbering operations were abolished to establish the protected areas of the park. Travel writer Horace Kephart, for whom Mount Kephart was named, and photographer George Masa were instrumental in fostering the development of the park.[5] Former Governor Ben W. Hooper of Tennessee was the principal land purchasing agent for the park,[6] which was officially established on June 15, 1934. During the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Works Progress Administration, and other federal organizations made trails, fire watchtowers, and other infrastructure improvements to the park and Smoky Mountains.

It was also a site for filming of parts of Disney's hit 1950s TV series, Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier.

This park was designated an International Biosphere Reserve in 1976, was certified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983, and became a part of the Southern Appalachian Biosphere Reserve in 1988.[7]

A 75th anniversary re-dedication ceremony was held on September 2, 2009. Among those in attendance were all four US Senators, the three US Representatives whose districts include the park, the governors of both states, and Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar. Tennessee native, singer, and actress Dolly Parton also attended and performed.[8]

Geology

The majority of rocks in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park are Late Precambrian rocks that are part of the Ocoee Supergroup. This group consists of metamorphosed sandstones, phyllites, schists, and slate. Early Precambrian rocks are not only the oldest rocks in the park but also the dominant rock type in sites such as the Raven Fork Valley and upper Tuckasegee River between Cherokee and Bryson City. They primarily consist of metamorphic gneiss, granite, and schist. Cambrian sedimentary rocks can be found among the bottom of the Foothills to the northwest and in limestone coves such as Cades Cove.[9] One of the most visited attractions in the mountains is Cades Cove which is a window or an area where older rocks made out of sandstone surround the valley floor of younger rocks made out of limestone.

The oldest rocks in the Smokies are the Precambrian gneiss and schists which were formed over a billion years ago from the accumulation of marine sediments and igneous rock. In the Late Precambrian, the primordial ocean expanded and the more recent Ocoee Supergroup rocks formed from the accumulation of eroding land mass onto the continental shelf. In the Paleozoic Era, the ocean deposited a thick layer of marine sediments which left behind sedimentary rock. During the Ordovician Period, the collision of the North American and African tectonic plates initiated the Alleghenian orogeny that created the Appalachian range. During the Mesozoic Era rapid erosion of softer sedimentary rocks re-exposed the older Ocoee Supergroup formations.[10]

Natural features

Elevations in the park range from 876 feet (267 m) at the mouth of Abrams Creek to 6,643 feet (2,025 m) at the summit of Clingmans Dome. Within the park a total of sixteen mountains reach higher than 6,000 feet (1,830 m).[11]

The wide range of elevations mimics the latitudinal changes found throughout the entire eastern United States. Indeed, ascending the mountains is comparable to a trip from Tennessee to Canada. Plants and animals common in the country's Northeast have found suitable ecological niches in the park's higher elevations, while southern species find homes in the balmier lower reaches.

During the most recent ice age, the northeast-to-southwest orientation of the Appalachian mountains allowed species to migrate southward along the slopes rather than finding the mountains to be a barrier. As climate warms, many northern species are now retreating upward along the slopes and withdrawing northward,[12] while southern species are expanding.[13]

The park normally has very high humidity and precipitation, averaging from 55 inches (1,400 mm) per year in the valleys to 85 inches (2,200 mm) per year on the peaks. This is more annual rainfall than anywhere in the United States outside the Pacific Northwest and parts of Alaska and Hawaii. It is also generally cooler than the lower elevations below, and most of the park has a humid continental climate more comparable to locations much farther north, as opposed to the humid subtropical climate in the lowlands. The park is almost 95 percent forested, and almost 36 percent of it, 187,000 acres (76,000 ha), is estimated by the Park Service to be old growth forest with many trees that predate European settlement of the area.[14] It is one of the largest blocks of deciduous, temperate, old growth forest in North America.

The variety of elevations, the abundant rainfall, and the presence of old growth forests give the park an unusual richness of biota. About 10,000 species of plants and animals are known to live in the park, and estimates as high as an additional 90,000 undocumented species may also be present.

Park officials count more than 200 species of birds, 50 species of fish, 39 species of reptiles, and 43 species of amphibians, including many lungless salamanders. The park has a noteworthy black bear population, numbering about 1,500.[15] An experimental re-introduction of elk (wapiti) into the park began in 2001.

It is also home to species of mammals such as the raccoon, bobcat, two species of fox, river otter, woodchuck, beaver, two species of squirrel, opossum, coyote, white-tailed deer, chipmunk, two species of skunk, and various species of bats.

Over 100 species of trees grow in the park. The lower region forests are dominated by deciduous leafy trees. At higher altitudes, deciduous forests give way to coniferous trees like Fraser fir. In addition, the park has over 1,400 flowering plant species and over 4,000 species of non-flowering plants.

Attractions and activities

As of Nov. 29, 2016, The Great Smoky Mountain National Park was under evacuation orders, along with some towns and cities located nearby. Before hiking or participating in any activities, it is suggested that people look at all advisory information concerning the area.

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is a major tourist attraction in the region. Over 9 million tourists and 11 million non-recreational visitors traveled to the park in 2010, more than twice as many visitors as the Grand Canyon, the second most visited national park.[16] Surrounding towns, notably Gatlinburg, Pigeon Forge, Sevierville, and Townsend, Tennessee, and Cherokee, Sylva, Maggie Valley, and Bryson City, North Carolina receive a significant portion of their income from tourism associated with the park.

The two main visitors' centers inside the park are Sugarlands Visitors' Center near the Gatlinburg entrance to the park and Oconaluftee Visitor Center near Cherokee, North Carolina at the eastern entrance to the park. These ranger stations provide exhibits on wildlife, geology, and the history of the park. They also sell books, maps, and souvenirs. Unlike most other national parks, there is no entry fee to the park.[17]

U.S. Highway 441 (known in the park as Newfound Gap Road) bisects the park, providing automobile access to many trailheads and overlooks, most notably that of Newfound Gap. At an elevation of 5,048 feet (1,539 m), it is the lowest gap in the mountains and is situated near the center of the park, on the Tennessee/North Carolina state line, halfway between the border towns of Gatlinburg and Cherokee. It was here that in 1940, from the Rockefeller Memorial, Franklin Delano Roosevelt dedicated the national park. On clear days Newfound Gap offers arguably the most spectacular scenes accessible via highway in the park.

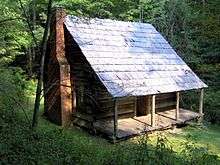

The park has a number of historical attractions. The most well-preserved of these (and most popular) is Cades Cove, a valley with a number of preserved historic buildings including log cabins, barns, and churches. Cades Cove is the single most frequented destination in the national park. Self-guided automobile and bicycle tours offer the many sightseers a glimpse into the way of life of old-time southern Appalachia. Other historical areas within the park include Roaring Fork, Cataloochee, Elkmont, and the Mountain Farm Museum and Mingus Mill at Oconaluftee.

Hiking

There are 850 miles (1,370 km) of trails and unpaved roads in the park for hiking, including seventy miles of the Appalachian Trail.[18] Mount Le Conte is one of the most frequented destinations in the park. Its elevation is 6,593 feet (2,010 m) — the third highest summit in the park and, measured from its base to its highest peak, the tallest mountain east of the Mississippi River. Alum Cave Trail is the most heavily used of the five paths en route to the summit. It provides many scenic overlooks and unique natural attractions such as Alum Cave Bluffs and Arch Rock. Hikers may spend a night at the LeConte Lodge, located near the summit, which provides cabins and rooms for rent (except during the winter season). Accessible solely by trail, it is the only private lodging available inside the park.

Another popular hiking trail leads to the pinnacle of the Chimney Tops, so named because of its unique dual-humped peaktops. This short but strenuous trek rewards nature enthusiasts with a spectacular panorama of the surrounding mountain peaks.

Both the Laurel Falls and Clingman's Dome trails offer relatively easy, short, paved paths to their respective destinations. The Laurel Falls Trail leads to a powerful 80-foot (24 m) waterfall, and the Clingman's Dome Trail takes visitors on an uphill climb to a fifty-foot observation deck, which on a clear day offers views for many miles over the Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia mountains.

In addition to day hiking, the national park offers opportunities for backpacking and camping. Camping is allowed only in designated camping areas and shelters. Most of the park's trail shelters are located along the Appalachian Trail or a short distance away on side trails. In addition to the Appalachian Trail shelters used mostly for extended backpacking trips there are three shelters in the park that are not located on the Appalachian Trail.

- The Mt. LeConte Shelter is located a short distance east of LeConte Lodge on The Boulevard Trail. It can accommodate 12 people per night, and is the only backcountry site in the entire park that has a permanent ban on campfires.

- The Kephart Shelter is located at the terminus of the Kephart Prong Trail which begins upstream of the Collins Creek Picnic Area. The shelter, situated along a tributary of the Oconaluftee River can accommodate 14 people.

- Laurel Gap Shelter is one of the more remote shelters in the park. Situated in a Beech forest swag between Balsam High Top and Big Cataloochee Mountain, the Laurel Gap Shelter can accommodate up to 14 people per night. This shelter is a popular base camp for peakbaggers exploring the heart of the Smokies wilderness.

Designated backcountry campsites are scattered throughout the park. A permit, available at ranger stations and trailheads, is required for all backcountry camping. Additionally, reservations are required for many of the campsites and all of the shelters. A maximum stay of one night, in the case of shelters, or three nights, in the case of campsites, may limit the traveler's itinerary.

Other activities

After hiking and simple sightseeing, fishing (especially fly fishing) is the most popular activity in the national park. The park's waters have long had a reputation for healthy trout activity as well as challenging fishing terrain. Brook trout are native to the waters, while both brown and rainbow were introduced to the area. Partially due to the fact of recent droughts killing off the native fish, there are strict regulations regarding how fishing may be conducted. Horseback riding (offered by the national park and on limited trails), bicycling (available for rent in Cades Cove) and water tubing are all also practiced within the park.

Historic areas within the national park

The park service maintains four historic districts and one archaeological district within park boundaries, as well as nine individual listings on the National Register of Historic Places. Notable structures not listed include the Mountain Farm Museum buildings at Oconaluftee and buildings in the Cataloochee area. The Mingus Mill (in Oconaluftee) and Smoky Mountain Hiking Club cabin in Greenbrier have been deemed eligible for listing.

Historic districts

- Cades Cove Historic District

- Elkmont Historic District

- Oconaluftee Archaeological District

- Noah Ogle Place

- Roaring Fork Historic District

Individual listings

- Alex Cole Cabin

- Clingmans Dome Observation Tower

- Hall Cabin (in Hazel Creek area)

- John Messer Barn

- John Ownby Cabin

- Oconaluftee Baptist Church (also called Smokemont Baptist Church)

- Tyson McCarter Place

- Mayna Treanor Avent Studio

- Little Greenbrier School

- Walker Sisters Place

Electric vehicles

The National Park Service (NPS) announced in late 2001 that it would use electric vehicles (EVs) provided by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) for a research project in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park to evaluate the vehicles' performance in mountainous terrain. The NPS said the EVs will be on loan from TVA for two years and will be used by park service staff at Cades Cove and the Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont to determine the benefits provided by these vehicles versus standard gasoline-fueled vehicles.[19]

Air pollution

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is considered the most polluted national park according to a 2004 report by the National Parks Conservation Association. From 1999 to 2003, the park recorded approximately 150 unhealthy air days, the equivalent of about one month of unhealthy air days per year.[20][21] In 2013, Colorado State University reported that, due to the passing of the United States Clean Air Act in 1970 and the subsequent implementation of the Acid Rain Program there was a "significant improvement" to the air quality in the Great Smoky Mountains from 1990 to 2010.[22][23]

See also

- Great Smoky Mountains Association

- Great Smoky Mountains Heritage Center

- Wildflowers of the Great Smoky Mountains

Notes

- 1 2 "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ↑ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ↑ GSMNP main page - National Park Service

- ↑ GSMNP stories - National Park Service

- 1 2 The National Parks: America's Best Idea. Ken Burns, broadcast on PBS.

- ↑ "Ben W. Hooper". tennesseeencyclopedia.net. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ MAB Biosphere Reserves Directory - UNESCO

- ↑ "Wide-ranging celebration to honor 75th anniversary of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park". Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- ↑ Moore, Harry (1988). A Roadside Guide to the Geology of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. p. 32.

- ↑ Houk, Rose, 1993, Great Smoky Mountains: A Natural History Guide, Mariner Books, pp 10-17, ISBN 978-0395599204

- ↑ "Natural Features & Ecosystems". US National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Becky Johnson. "A sanctuary for scientists: Smokies' slopes seen as frontier in global warming research". Smoky Mountain News. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ "Climate Change in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park" (PDF). Macalester College. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ Mary Byrd Davis (23 January 2008). "Old Growth in the East: A Survey. North Carolina" (PDF).

- ↑ "Black Bears - Great Smoky Mountains National Park". National Park Service.

- ↑ "Park Statistics - Great Smoky Mountains National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ Why No Entrance Fee? National Park Service.

- ↑ GSMNP Just for Fun, National Park Service

- ↑ "NPS Launches Program to Study EVs in Park.(National Park Service using electric vehicles)(Brief Article)". 13 December 2001. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ Feanny, Camille (2004-06-24). "Smokies top list of most polluted parks". CNN. Retrieved 2009-12-28.

- ↑ "New Report Ranks Five Most-Polluted National Parks". National Parks Conservation Association. 2004-06-24. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ↑ Wenzler, Mark (12 March 2013). "New Report: Air Quality in the Smokies Is Headed in the Right Direction · National Parks Conservation Association". Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Dimas, Jennifer (7 March 2013). "Reducing Pollution at National Parks: Colorado State University Scientists Demonstrate Significant Improvements in Air Quality, Visibility - News & Information - Colorado State University". Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

References

- Saferstein, Mark. 2004. Great Smoky Mountains. 22nd ed. American Parks Network.

- Tilden, Freeman. 1970. The National Parks

- "Old-Time Smoky Mountain Music: 34 Historic Songs, Ballads, and Instrumentals Recorded in the Great Smoky Mountains by 'Song Catcher' Joseph S. Hall" (CD released by the Great Smoky Mountains Association, 2010).

- Pierce, Daniel S. The Great Smokies: From Natural Habitat to National Park. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2000.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Great Smoky Mountains National Park. |

- Official site: Great Smoky Mountains National Park

- Species Mapper

- Lookout Rock webcam and current air quality data

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park at NASA Earth Observatory

- Official Nonprofit Expert Nature Hikes

- Guide to records (general administrative files) from the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

- Great Smoky Mountains Association — Nonprofit Partner of the Park, videos, photos, maps, and more