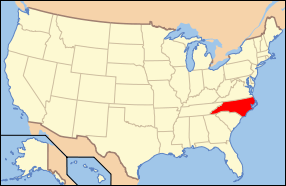

Fort Dobbs (North Carolina)

|

Fort Dobbs | |

|

Detail of a 1770 map of North Carolina by John Collett depicting the locations of Fort Dobbs, the Yadkin and Catawba Rivers, and Salisbury.[1] | |

| |

| Nearest city | Statesville, North Carolina |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°49′18″N 80°53′42″W / 35.82167°N 80.89500°WCoordinates: 35°49′18″N 80°53′42″W / 35.82167°N 80.89500°W |

| Area | 9.5 acres (3.8 ha; 0.0148 sq mi) |

| Built | 1755–1756 |

| Architect | Arthur Dobbs, Hugh Waddell |

| Architectural style | Log blockhouse |

| MPS | Iredell County MRA (AD) |

| NRHP Reference # | 70000458[2] |

| Added to NRHP | September 15, 1970 |

Fort Dobbs was an 18th-century fort in the Yadkin–Pee Dee River Basin region of the Province of North Carolina, near what is now Statesville in Iredell County. Used for frontier defense during and after the French and Indian War, the fort was built to protect the British settlers of the western portion of what was then Rowan County, and served as a vital outpost for soldiers, traders, and colonial officials. Fort Dobbs' primary structure was a blockhouse with log walls, surrounded by a palisade and moat. It was intended to provide protection against Cherokee, Catawba, Shawnee, Delaware and French raids into North Carolina.

The fort's name honored Arthur Dobbs, the colonial Governor of North Carolina from 1754 to 1765, who played a role in designing the fort and authorized its construction. When in use, it was the only fort on the frontier between South Carolina and Virginia. Between 1756 and 1760, the blockhouse was garrisoned by a variable number of soldiers, many of whom were sent to fight in Pennsylvania and the Ohio River Valley during the French and Indian War. On February 27, 1760, the fort was the site of an engagement between Cherokee warriors and provincial soldiers that ended in a victory for the provincials. After this battle and other attacks by Cherokee warriors on British forts and settlements in the Anglo-Cherokee War, the southern British colonies launched a devastating counterattack against the Cherokee in 1760.

Fort Dobbs was abandoned after 1766, and disappeared from the landscape. Archaeological work in the 20th century and historical research in 2005 and 2006 led to the discovery of the fort's exact location and probable appearance. The site on which the fort sat is now operated by North Carolina's Division of State Historic Sites and Properties as Fort Dobbs State Historic Site, and supporters of the site have developed plans for the fort's reconstruction.

Background

Settlement of the Carolina back-country

In 1747, approximately 100 men of suitable age to serve in the colonial militia lived in North Carolina west of present-day Hillsborough. Within three years, most of North Carolina's population increase, driven mainly by the immigration of Scots-Irish and German settlers traveling from Pennsylvania on the Great Wagon Road, was occurring in seven western counties created after 1740.[3] By 1754, six western counties—Orange, Granville, Johnston, Cumberland, Anson, and Rowan—held around 22,000 residents out of the colony's total population of 65,000.[4]

Construction

In 1755, Governor Arthur Dobbs ordered the construction of a fortified log structure for the protection of settlers in Rowan County from various Native American threats, including assaults from Cherokee, Catawba, Shawnee, and Delaware raiding parties.[5] Dobbs stated in a letter on August 24, 1755, to the Board of Trade that the fort was needed "to assist the back settlers and be a retreat to them as it was beyond the well settled Country, only straggling settlements behind them, and if I had placed [Waddell's garrison] beyond the Settlements without a fortification they might be exposed, and be no retreat for the Settlers, and the Indians might pass them and murder the Inhabitants, and retire before they durst go to give them notice".[6][7] The new frontier settlements required regular protection, as the settlers in the area attributed many crimes and forms of harassment to denizens of nearby Catawba and Cherokee towns. Furthermore, Governor Dobbs was concerned for his own investments, as he owned more than 200,000 acres (81,000 ha; 310 sq mi) of land on the Rocky River, approximately 15 miles (24 km) south of the Fourth Creek Meeting House.[8][9]

The North Carolina Legislature set aside a sum of £10,000 for the construction of the fort in 1755, as well as for the raising of several companies of provincial soldiers to defend the frontier.[10] Provincial soldiers, known by the shortened name "provincials", were soldiers raised, clothed, and paid by the individual British colonies, although they were at various times armed and supplied by the regular British Army.[11] The total cost of the fort was only £1,000.[12] By comparison, Fort Stanwix in New York, begun in 1758 in a then-modern star fort style, cost £60,000 to erect,[13] while the construction of Fort Prince George in South Carolina cost that province's House of Commons £3,000.[14]

Dobbs likely had a role in designing the fort, as he had designed at least one other fort in North Carolina, as well as a number of structures in Ireland.[15][16] Hugh Waddell, a Scotch-Irish soldier who had close ties to Governor Dobbs and who was the commander of a company of provincial soldiers in 1755, built the fort's blockhouse and palisade using labor provided by his soldiers, and named it after the governor. The land on which the fort was to be located was a part of a 560-acre (230 ha; 0.88 sq mi) tract owned first by one James Oliphant, then by a Fergus Sloan. Part of the same tract was used for the Fourth Creek Congregation Meeting House (so named because the settlement was on the fourth creek one would pass traveling west on the South Yadkin River from Salisbury) in 1755, which was the principal structure around which the modern city of Statesville was founded.[8] After construction was completed, Fort Dobbs was the only military installation on the colonial frontier between Virginia and South Carolina.[17]

Description and effectiveness

By June 1756, Waddell had substantially completed construction on the fort. Francis Brown and future governor Richard Caswell, commissioners appointed by Dobbs to inspect frontier defenses,[18] wrote the following report to the North Carolina General Assembly on December 21, 1756:

[Brown and Caswell] had likewise viewed the State of Fort Dobbs and found it to be a good and Substantial Building of the Dimentions [sic] following (that is to say) The Oblong Square fifty three feet by forty, the opposite Angles Twenty four feet and Twenty-Two In height Twenty four and a half feet as by the Plan annexed Appears, The Thickness of the Walls which are made of Oak Logs regularly Diminished from sixteen Inches to Six, it contains three floors and there may be discharged from each floor at one and the same time about one hundred Musketts [sic] the same is beautifully scituated [sic] in the fork of Fourth Creek a Branch of the Yadkin River. And that they also found under Command of Capt Hugh Waddel Forty six Effective men Officers and Soldiers as by the List to the said Report Annexed Appears the same being sworn to by the said Capt in their Presence the said Officers and Soldiers Appearing well and in good Spirits.[19]

The commissioners generally found the defenses of the rest of the North Carolina frontier to be inadequate.[20] In 1756, the North Carolina General Assembly petitioned King George II for assistance, stating that the frontier remained in a relatively defenseless state. The address to the king further noted that after the fall of Fort Oswego to the French and their native allies in that year, the legislators did not believe that Fort Dobbs would provide a substantial defensive advantage.[20] Settlers west of the Yadkin River were subjected to regular attacks so that between 1756 and 1759, even after the construction of Fort Dobbs, the population of settlers in the area declined from approximately 1,500 to 800. Catawba raiding parties even struck as far as the largest western settlement, Salisbury, breaking into a session of court held by Peter Henley, Royal Chief Justice of the Province of North Carolina.[21]

In 1759, Waddell ordered six swivel guns for use by North Carolina's military. Oral tradition in Iredell County holds that two such swivel guns were mounted at Fort Dobbs, but evidence of the exact quantity present at the fort has not been conclusively established.[22][23]

Use and conflict

Early uses

Between 1756 and 1760, Fort Dobbs was used as a base of operations for Waddell's company of provincials.[25] Dobbs also employed Waddell and the fort to conduct diplomacy with the province's native neighbors. The governor gave specific instructions on July 18, 1756, in a letter sent from New Bern to Waddell, who had just finished supervising the construction of the fort, and two other men, stating:

I have given Orders to make you or any two of You a Commission as often as Necessary to go and make complaints to the Chief Sachims of the Cherokee and Catauba Nations when any Murders Robberies or Depredations are made by any of their People upon the English and to know whether it is done by their Orders or Allowance and if not to give up the Delinquents if Known or then when not Known that they should give Strict Orders to their Hnnters [sic] and warriors not to rob Kill or abuse the English Planters their Bretheren and Destroy their Horses cows Swine or Corn and if they should afterwards do it that the English their Bretheren would be Obliged to repell force with force and in Case they dont own to what Nation they belong that they will be treated as other Indian Nations in alliance with our Enemies the French who are now Spiriting them up to make war against us.[26]

In addition to warning nearby natives against attacking settlers in the Carolinas, Dobbs also charged Waddell with attempting to keep peace with the Catawba. In one instance, Dobbs instructed Waddell to turn over a settler who had killed a Catawba hunter in order to placate the hunter's tribesmen, in the event assurances that the settler would be brought to justice under the province's laws did not persuade the Catawba to remain friendly with North Carolina.[26]

In 1756, Dobbs also approved the construction of another fort, this time in lands claimed by the Catawba, as well as both Carolinas, near modern-day Fort Mill, South Carolina. Workmen under Waddell's command began construction in 1756, but in 1757, Catawba leaders, influenced by South Carolina Governor William Lyttelton, informed North Carolina's government that they no longer wished for this second fort to be built, and construction of the second fort was permanently halted.[27]

At the commencement of the French and Indian War, settlers in the nearby Fourth Creek Congregation settlement sought protection by remaining in close proximity to the fort.[25] During the early stages of that war, and well into 1759, the fort housed only two soldiers; the remaining members of the frontier company had returned to their homes or, like Waddell, had gone to fight in Pennsylvania.[28] In Waddell's absence, the fort was under the command of Captain Andrew Bailey.[17]

Decline and fall of Anglo-Cherokee relations

During the Anglo-Cherokee War, which occurred during the later years of the French and Indian War, the fort served as the base for a company of North Carolina provincials tasked with repelling Cherokee raids in the western portion of the province when hostilities broke out between that tribe and the British provinces in 1758. The Anglo-Cherokee War began in 1758 after the capture of Fort Duquesne by the British and their native allies, including the Cherokee. After that fort was taken, the focus of combat in the French and Indian War moved northward, further away from the Cherokee homelands, and a number of Cherokee warriors felt that their contributions to the war effort were unappreciated. Several colonies, including Virginia and South Carolina, promised the Cherokee that they would build forts near their lands to protect them from hostile attack in exchange for warriors that had been supplied for the war effort.[29] In Virginia's case, such promises were never fulfilled, and in South Carolina, the promised military presence eventually caused more concern in the Cherokee leadership than it alleviated.[30] Long-term trends in English settlement, which encroached past the border between the Cherokee and South Carolina that had been set by treaty at Long Cane Creek (west of modern-day Greenwood, South Carolina), elevated Cherokee concern that vital hunting grounds would be permanently lost.[31]

Several pro-French and pro-Creek leaders among the Cherokee pushed for violent actions against British settlers, despite the opposition of pro-British Cherokee leaders. Eventually tensions between the Cherokee and the colonists reached a head when Cherokee warriors were attacked by settlers in Virginia, including an unknown number who were ambushed by frontier militia groups who alleged that the Cherokee had slaughtered cattle and stolen horses that belonged to Virginian settlers.[29] The Virginians attempted to sell the massacred Cherokee warriors' scalps to the government of Virginia as the scalps of Shawnee warriors (for which the British had set a bounty), an act that insulted the Cherokee. After this and similar occurrences, younger, pro-French leaders among the Cherokee instigated attacks against settlers throughout the frontier. The colonial military of the South Carolina, which considered the Cherokee towns to be within its sphere of influence, responded by assaulting Cherokees, taking more scalps from the Cherokee and selling them to British authorities, and the colonial government refused to engage in negotiations with even the most sympathetic Cherokee leaders.[32]

War comes to Fourth Creek

Throughout 1759 and 1760, small Cherokee bands attacked homesteads and communities on the frontier, oftentimes taking scalps from the British settlers. In raids on April 25 and 26, 1759, several parties of Cherokee led by Moytoy of Citico struck at settlements on the Yadkin and Catawba Rivers against the wishes of Cherokee leaders such as Attakullakulla, killing around 19 men, women and children, and taking more than 10 scalps from those killed, including eight scalps from settlers living on Fourth Creek.[33] This violence damaged peace talks between Attakullakulla and South Carolina governor William Lyttelton, who considered the territory west of the Yadkin River in North Carolina to be within South Carolina's sphere of influence.[34] The violence committed by the Cherokee against British settlers continued, which in turn caused the colonial authorities to seek better relations with the Creek and Catawba nations.[35] The Catawba, who were allied to the provinces of North and South Carolina, were only able to provide minimal assistance to the English in the defense of their frontiers, as that tribe's settlements had been decimated by smallpox in 1759 and early 1760.[36] During this period of violence, members of Daniel Boone's family, who had settled in the area, took refuge in the fort, although Boone himself went to Culpeper County, Virginia with his wife and children.[37] Several scholars have speculated that Boone himself served under Waddell as a member of the frontier provincial company.[38][39]

All remaining goodwill was lost between Lyttelton's government in Charleston, the North Carolina government, and the pro-peace Cherokee when Lyttelton ordered the detention of several peace delegations led by headmen Oconostota, Tistoe, and "Round O", despite having previously guaranteed them safe passage. Lyttelton had the delegations put under armed guard, and secured them at Fort Prince George.[40] A peace arrangement was agreed upon in December, 1759, although the Cherokee agreed under duress, and the pro-war faction of the Cherokee did not obey its terms. Several of the signatories for the Cherokee intended to disavow their promises as soon as they were able, in order to seek retribution for the capture of their peace delegations.[41]

Full-blown war broke out across the Carolina frontier by January, 1760. Between January and February, 1760, more than 77 settlers on the Carolina frontier were killed by Cherokee war parties, and the British settlement boundaries had been effectively pushed back by more than 100 miles.[42] Many of the Cherokee captives held at Fort Prince George were massacred in mid-February, 1760 after an attempt was made to rescue them, in which Ensign Richard Coytmore, the commanding officer of that fort who was much maligned by the Cherokee, was killed.[43] Lyttelton, who was soon appointed Governor of Jamaica, requested assistance from Dobbs, but North Carolina's militia could not be convinced to serve outside of its home province due to long-standing custom.[44]

Battle

Waddell and his provincials returned to Fort Dobbs after the fall of Fort Duquesne.[17] The fort's sole engagement occurred when a band of Cherokee warriors attacked on the night of February 27, 1760. During that battle, approximately 10 to 13 warriors died, and one or two provincial soldiers were wounded, while one young boy was killed.[45] Future American Revolutionary War officer and North Carolina politician Griffith Rutherford, at the time a Captain, may have fought as during the battle under Waddell's command.[46] The Cherokee made off with several horses belonging to Waddell's company, but were ultimately repulsed. Waddell described the action in an official report to the Governor on February 29, 1760:

For several days I observed that a small party of Indians were constantly about the fort, I sent out several small parties after them to no purpose, the evening before last between 8 and 9 o'clock I found by the dogs making an uncommon noise there must be a party nigh a spring which we sometimes use. As my garrison is but small, and I was apprehensive it might be a scheme to draw out the garrison, I took out Captain Bailie who with myself and party made up ten; we had not marched 300 yards from the fort when we were attacked by at least 60 or 70 Indians. I had given my party orders not to fire until I gave the word, which they punctually observed: we received the Indians [sic] fire: when I perceived they had almost all fired, I ordered my party to fire which we did not further than 12 steps each loaded with a bullet and seven buck shot, they had nothing to cover them as they were advancing either to tomahawk or make us prisoners: they found the fire very hot from so small a number which a good deal confused them; I then ordered my party to retreat, as I found the instant our skirmish began another party had attacked the fort, upon our reinforcing the garrison the Indians were soon repulsed with I am sure a considerable loss, from what I myself saw as well as those I can confide in they could not have had less than 10 or 12 killed or wounded, and I believe they have taken six of my horses to carry off their wounded ... On my side I had 2 men wounded one of whom I am afraid will die as he is scalped, the other is in a way of recovery and one boy killed near the fort whom they durst not advance to scalp. I expected they would have paid me another visit last night, as they attack all fortifications by night, but they did not like their reception.[45]

At around the same time as this attack occurred, Cherokee war parties attacked Fort Loudoun, Fort Prince George, and Ninety-Six, South Carolina.[42] After this wave, Cherokee war parties continued to threaten Bethabara in the Wachovia Tract, Salisbury, and other settlements in the Yadkin, Catawba, and Broad river basins.[47] The engagement at Fort Dobbs and settlements in the North Carolina Piedmont led the government of North Carolina to join South Carolina and Virginia in their campaign against the Cherokee in their own settlements in North and South Carolina, known as the "Middle" and "Lower Towns". Initially, though, Governor Dobbs notified Governor Lyttelton of South Carolina that the North Carolina militia would be unable to assist because it could not be compelled to leave the province.[48][49] The following year, in 1761, various delays hampered the movement of North Carolina troops.[50] In the meantime, approximately 15 Cherokee towns of between 350 and 600 inhabitants were destroyed.[51][52] The campaign against the Cherokees displaced approximately 5,000 tribe members,[51] and permanently pushed that tribe's zone of control west, across the Appalachian Mountains.[53]

Post-war history

At the conclusion of the conflict between the French and the British, and after hostilities between the provincials and Cherokee ended with the rolling back of Cherokee boundaries in western North Carolina, the fort quickly became obsolete. On March 7, 1764, the North Carolina General Assembly's Committee on Public Claims recommended to Governor Dobbs that stores and supplies be removed from the fort to spare the government further expense in upkeep.[54] By 1766, the fort was formally abandoned.[55]

Site preservation and archaeology

Archaeological exploration of the site first occurred in 1847, when a group of local residents attempted to locate a rumored original cannon on the site. Evidence of this dig was discovered in the 21st century in a later archaeological study.[56] In 1909, local residents established the Fort Dobbs Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. That same year, the owners of the parcel of land on which the Fort Dobbs site was located donated 1,000 square feet (93 m2) containing the fort's remains to the Fort Dobbs Chapter. By 1910, the Chapter erected a stone marker at the site, and in 1915, it purchased the 10 acres of land surrounding the original donated parcel. In 1969, the North Carolina General Assembly appropriated $15,000 to purchase the property, to be matched by funds raised locally by the Iredell County Historical Society; these purchases were made in 1971 and 1973. By 1976, the land was opened as a historic site.[57]

By 2006, archaeologists and historical researchers had determined the exact location of Fort Dobbs, and had located the post-hole foundations of the former log structure. Excavation began in 1967, and by 1968, the site of the fort was confirmed. In 1967, Stanley South, an archaeologist and proponent of processual archaeology, discovered that by overlaying a transparency depicting a survey of the Fort Dobbs site done in the mid-18th-century on a modern aerial photograph, evidence of the surveyed lines could still be discerned in the modern terrain. Additionally, excavations revealed a moat that surrounded the blockouse, as well as trash in the moat contemporary with the fort.[58] Early archaeological work concentrated specifically on the moat and a depression called the "cellar", which South believed served as a storage space in the middle of the fort grounds, and which later researchers believe was directly underneath the blockhouse.[59] Archaeological work has unearthed evidence of a palisade surrounding the blockhouse, in a similar fashion to other French and Indian War-era forts such as Fort Shirley near Heath, Massachusetts, and Fort Prince George.[60]

In 2006, a researcher affiliated with East Carolina University, Lawrence Babits, presented a study and a reconstruction plan that has been accepted by the Friends of Fort Dobbs, the 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that supports the site, and the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.[61] In his plan, Babits postulated that Dobbs most likely played a role in designing the fort, basing the design on forts with which Dobbs had first-hand experience as an administrator in Scotland, such as Bernera Barracks near Glenelg and Ruthven Barracks near Kingussie.[62] From these comparisons, the contemporary description of the fort, and the soil record, Babits concluded that the "opposite angles" described by Francis Brown in 1756 actually referred to "flankers", or square wooden structures attached to the corner of the fort that would have allowed defending soldiers to shoot into the flank of any attacking forces surrounding the building.[63]

Historic site

The State of North Carolina maintains and operates the area as Fort Dobbs State Historic Site. The visitor center, located in a log cabin constructed from parts of local, 19th-century log structures, features displays about both the colonial fort and the French and Indian War period.[64] Outdoor trails lead visitors through the excavated ruins of the fort. Events, including many living history demonstrations, are held throughout the year at the fort.[65] The Fort Dobbs site remains the only historic site in the state related to the French and Indian War.[66]

Yearly attendance at the site is about 27,000 people. As of 2013, a campaign to renovate the site and restore much of Fort Dobbs is underway with the goal of raising $2.6 million for the project. A grant of $150,000 was given by the Institute of Museum and Library Services for the design of the project.[67] In 2010, the Friends of Fort Dobbs pledged $500,000 to the North Carolina Historic Sites program for the reconstruction of the fort.[68] On January 5, 2013, Governor Bev Perdue signed a lease on behalf of the State to the Friends organization, allowing the nonprofit group to hire a private contractor for the fort's reconstruction.[69]

See also

- Colonial American military history

- Fort Johnston (North Carolina)—contemporary colonial North Carolina fort

- French and Indian Wars

References

Footnotes

- ↑ "A Compleat map of North Carolina from an actual survey". North Carolina Maps. UNC Digital Collections. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ↑ National Park Service (July 9, 2010). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Ramsey 1964, p. 23.

- ↑ Lefler & Powell 1973, p. 218.

- ↑ Lefler & Powell 1973, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Miller 2011, p. 26.

- ↑ Saunders 1887, p. 357, Letter from Arthur Dobbs to the Board of Trade of Great Britain, August 24, 1755

- 1 2 Ramsey 1964, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Clarke 1957, p. 120, noting that Dobbs had approximately 75 families on his lands, of which between 30 and 40 were Scotch–Irish, and 22 were German or Swiss.

- ↑ Waddell 1890, p. 31.

- ↑ Brumwell 2002, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Saunders 1887, p. 572, Letter from Arthur Dobbs to the Board of Trade of Great Britain, March 15, 1756

- ↑ Greene 1925, pp. 604–608.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Babits & Pecoraro 2008, pp. 3, 15.

- ↑ Saunders 1887, pp. 597–98, Letter from Arthur Dobbs to John Campbell, Earl of Loudoun, July 10, 1756

- 1 2 3 Walbert, David. "8.2 Fort Dobbs and the French and Indian War in North Carolina". LearnNC.org. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Education. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ↑ Saunders 1887, p. xlviii, Preface to Volume 5

- ↑ Saunders 1887, p. 849, Minutes of the Lower House of the North Carolina General Assembly, May 20, 1757

- 1 2 Saunders 1887, p. xlix, Preface to Volume 5

- ↑ Lefler & Powell 1973, p. 143.

- ↑ Keever 1976, p. 57.

- ↑ Babits & Pecoraro 2008, pp. 17.

- ↑ Waddell 1890.

- 1 2 Branch 1996, p. 459.

- 1 2 Saunders 1887, pp. 604–605, Letter of Arthur Dobbs to Hugh Waddell, [Alexander Osborne], and Colonel Alexander of July 18, 1756

- ↑ Cashion 1996, p. 104.

- ↑ Ramsey 1964, p. 196.

- 1 2 Perdue 1985, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, p. 22.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, pp. 72–78.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, p. 76.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, pp. 77–87.

- ↑ Lee 2011, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Lofaro 2010, p. 17.

- ↑ Lofaro 2010, p. 18.

- ↑ Draper 1998, p. 157.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, pp. 102–104, 109.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, p. 109.

- 1 2 Oliphant 2001, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, p. 111.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, p. 112.

- 1 2 Ramsey 1964, p. 197.

- ↑ MacDonald 2006, p. 30.

- ↑ Lee 2011, p. 80.

- ↑ Nester 2000, p. 194.

- ↑ Tortora 2015, p. 131-32.

- ↑ Maass 2013, p. 112-14.

- 1 2 Anderson 2006, p. 402.

- ↑ Oliphant 2001, pp. 2–4, Oliphant estimates total Cherokee population at the time to have been between 9,000 and 11,000, with about 3,000 warriors

- ↑ Ramsey 1964, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ Clark 1907, p. 839, Report by the Committee of both Houses of the North Carolina General Assembly concerning public claims of March 7, 1764

- ↑ Lefler & Powell 1973, p. 149.

- ↑ Babits & Pecoraro 2008, p. 47.

- ↑ McCullough 2001, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ South 2005, pp. 191–192.

- ↑ Babits & Pecoraro 2008, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Coe 2006, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ "Archaeology". Fort Dobbs website. Friends of Fort Dobbs, Inc. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ↑ Babits & Pecoraro 2008, pp. 21–26.

- ↑ Babits & Pecoraro 2008, pp. 230–234, Appendix II, "Reconstructing Fort Dobbs"

- ↑ "Hours, Daily Programs, Facilities". Fort Dobbs website. Friends of Fort Dobbs, Inc. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- ↑ McCullough, Gary (November 10, 2012). "Fort Dobbs shows life on early frontier". Raleigh News & Observer. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ↑ "Public Hearing on Fort Dobbs, Commissioners Want Further Input from Supporters, Opponents". Charlotte Observer. January 23, 2005. p. 2J.

- ↑ "Restoration planned for Fort Dobbs". Triad Business Journal. June 29, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ↑ Fuller, Bethany (September 22, 2010). "Fort Dobbs supporters raise $500K for project". Mooresville Tribune. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ↑ Spencer, Preston (January 18, 2013). "Fort Dobbs clears hurdle to building structure". Statesville Record & Landmark. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

Bibliography

- Anderson, William (2006). "Etchoe, Battle of". In Powell, William S. Encyclopedia of North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3071-0.

- Babits, Lawrence E.; Pecoraro, Tiffany A. (2008). Fort Dobbs, 1756–1763: Iredell County, North Carolina : final archaeological report. Greenville, NC: East Carolina University. OCLC 240386230.

- Branch, Paul (2006). "Fort Dobbs". In Powell, William S. Encyclopedia of North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3071-0.

- Brumwell, Stephen (2002). Redcoats: The British Soldier and War in the Americas, 1755–1763. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67538-3.

- Cashion, Jerry C. (1996). "Waddell, Hugh". In Powell, William S. Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. Volume 6 (T–Z). Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-6699-3.

- Clark, Walter, ed. (1907). Colonial and State Records of North Carolina. Volume 22. Raleigh, NC: State of North Carolina. OCLC 1969836.

- Clarke, Desmond, ed. (1957). Arthur Dobbs, Esquire, 1689-1765: Surveyor-General of Ireland, Prospector and Governor of North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. OCLC 192097083.

- Coe, Michael (2006). The Line of Forts: Historical Archaeology on the Colonial Frontier of Massachusetts. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England. ISBN 978-1-58465-542-8.

- Draper, Lyman Copeland (1998). The Life of Daniel Boone. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0979-5.

- Greene, Nelson (1925). History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614–1925: Covering the Six Counties of Schenectady, Schoharie, Montgomery, Fulton, Herkimer, and Oneida. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co. OCLC 2495714.

- Keever, Homer (1976). Iredell, Piedmont County. Statesville, NC: Iredell County Bicentennial Commission. OCLC 3187215.

- Lee, E. Lawrence (2011). Indian Wars in North Carolina: 1663–1763. Raleigh, NC: Office of Archives and History, NC Dept. of Cultural Resources. ISBN 978-0-86526-084-9.

- Lefler, Hugh T.; Powell, William S. (1973). Colonial North Carolina: A History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-13536-1.

- Lofaro, Michael (2010). Daniel Boone: An American Life. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2278-3.

- McCullough, Gary L. (2001). North Carolina's State Historic Sites. Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair. ISBN 0-89587-241-2.

- MacDonald, James M. (2006). Politics of the Personal in the Old North State: Griffith Rutherford in Revolutionary North Carolina (PDF) (Ph.D.). Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College. OCLC 75633820. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- Maass, John R. (2013). The French and Indian War in North Carolina: The Spreading Flames of War. Charleston, SC: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60949-887-0.

- Miller, David W. (2011). The Taking of American Indian Lands in the Southeast: A History of Territorial Cessions and Forced Relocation, 1607–1840. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-6277-3.

- Nester, William R. (2000). The First Global War: Britain, France, and the Fate of North America, 1756–1775. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96771-9.

- Oliphant, John (2001). Peace and War on the Anglo-Cherokee Frontier, 1756–1763. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2637-3.

- Perdue, Theda (1985). Native Carolinians: The Indians of North Carolina. Raleigh, NC: Division of Archives and History, N.C. Dept. of Cultural Resources. ISBN 0-86526-217-9.

- Ramsey, Robert (1964). Carolina Cradle: Settlement of the Northwest Carolina Frontier, 1747–1762. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4189-1.

- Saunders, William L., ed. (1887). Colonial and State Records of North Carolina. Volume 5. Raleigh, NC: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State. OCLC 1969836.

- South, Stanley A. (2005). An Archaeological Evolution. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, Inc. ISBN 0-387-23401-2.

- Tortora, Daniel J. (2015). Carolina in Crisis: Cherokees, Colonists, and Slaves in the American Southeast, 1756–1763. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-2122-7.

- Waddell, Alfred (1890). A Colonial Officer and His Times, 1754–1773: A Biographical Sketch of Hugh Waddell. Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Co. OCLC 16153240.

External links

- Friends of Fort Dobbs, Inc.

- North Carolina State Historic Sites page

- North Carolina History Project, "Fort Dobbs"