Heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs. A heretic is a proponent of such claims or beliefs.[1] Heresy is distinct from both apostasy, which is the explicit renunciation of one's religion, principles or cause,[2] and blasphemy, which is an impious utterance or action concerning God or sacred things.[3]

The term is usually used to refer to violations of important religious teachings, but is used also of views strongly opposed to any generally accepted ideas.[4] It is used in particular in reference to Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.[5]

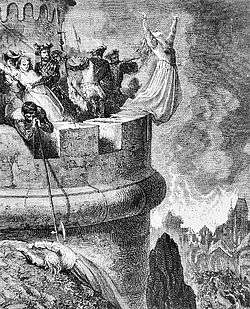

In certain historical Christian, Islamic and Jewish cultures, among others, espousing ideas deemed heretical has been and in some cases still is subjected not merely to punishments such as excommunication, but even to the death penalty.

Etymology

The term heresy is from Greek αἵρεσις originally meant "choice" or "thing chosen",[6] but it came to mean the "party or school of a man's choice"[7] and also referred to that process whereby a young person would examine various philosophies to determine how to live. The word "heresy" is usually used within a Christian, Jewish, or Islamic context, and implies slightly different meanings in each. The founder or leader of a heretical movement is called a heresiarch, while individuals who espouse heresy or commit heresy are known as heretics. Heresiology is the study of heresy.

Christianity

According to Titus 3:10 a divisive person should be warned two times before separating from him. The Greek for the phrase "divisive person" became a technical term in the early Church for a type of "heretic" who promoted dissension.[8] In contrast correct teaching is called sound not only because it builds up the faith, but because it protects it against the corrupting influence of false teachers.[9]

The Church Fathers identified Jews and Judaism with heresy. They saw deviations from orthodox Christianity as heresies that were essentially Jewish in spirit.[10] Tertullian implied that it was the Jews who most inspired heresy in Christianity: "From the Jew the heretic has accepted guidance in this discussion [that Jesus was not the Christ.]" Saint Peter of Antioch referred to Christians that refused to venerate religious images as having "Jewish minds".[10]

The use of the word "heresy" was given wide currency by Irenaeus in his 2nd century tract Contra Haereses (Against Heresies) to describe and discredit his opponents during the early centuries of the Christian community. He described the community's beliefs and doctrines as orthodox (from ὀρθός, orthos "straight" + δόξα, doxa "belief") and the Gnostics' teachings as heretical. He also pointed out the concept of apostolic succession to support his arguments.[11]

Constantine the Great, who along with Licinius had decreed toleration of Christianity in the Roman Empire by what is commonly called the "Edict of Milan",[12] and was the first Roman Emperor baptized, set precedents for later policy. By Roman law the Emperor was Pontifex Maximus, the high priest of the College of Pontiffs (Collegium Pontificum) of all recognized religions in ancient Rome. To put an end to the doctrinal debate initiated by Arius, Constantine called the first of what would afterwards be called the ecumenical councils[13] and then enforced orthodoxy by Imperial authority.[14]

The first known usage of the term in a legal context was in AD 380 by the Edict of Thessalonica of Theodosius I,[15] which made Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire. Prior to the issuance of this edict, the Church had no state-sponsored support for any particular legal mechanism to counter what it perceived as "heresy". By this edict the state's authority and that of the Church became somewhat overlapping. One of the outcomes of this blurring of Church and state was the sharing of state powers of legal enforcement with church authorities. This reinforcement of the Church's authority gave church leaders the power to, in effect, pronounce the death sentence upon those whom the church considered heretical.

Within six years of the official criminalization of heresy by the Emperor, the first Christian heretic to be executed, Priscillian, was condemned in 386 by Roman secular officials for sorcery, and put to death with four or five followers.[16][17][18] However, his accusers were excommunicated both by Ambrose of Milan and Pope Siricius,[19] who opposed Priscillian's heresy, but "believed capital punishment to be inappropriate at best and usually unequivocally evil".[16] The edict of Theodosius II (435) provided severe punishments for those who had or spread writings of Nestorius.[20] Those who possessed writings of Arius were sentenced to death.[21]

For some years after the Reformation, Protestant churches were also known to execute those they considered heretics, including Catholics. The last known heretic executed by sentence of the Catholic Church was Spanish schoolmaster Cayetano Ripoll in 1826. The number of people executed as heretics under the authority of the various "ecclesiastical authorities"[note 1] is not known.[note 2]

Catholicism

In the Catholic Church, obstinate and willful manifest heresy is considered to spiritually cut one off from the Church, even before excommunication is incurred. The Codex Justinianus (1:5:12) defines "everyone who is not devoted to the Catholic Church and to our Orthodox holy Faith" a heretic.[27] The Church had always dealt harshly with strands of Christianity that it considered heretical, but before the 11th century these tended to centre around individual preachers or small localised sects, like Arianism, Pelagianism, Donatism, Marcionism and Montanism. The diffusion of the almost Manichaean sect of Paulicians westwards gave birth to the famous 11th and 12th century heresies of Western Europe. The first one was that of Bogomils in modern-day Bosnia, a sort of sanctuary between Eastern and Western Christianity. By the 11th century, more organised groups such as the Patarini, the Dulcinians, the Waldensians and the Cathars were beginning to appear in the towns and cities of northern Italy, southern France and Flanders.

In France the Cathars grew to represent a popular mass movement and the belief was spreading to other areas.[28] The Cathar Crusade was initiated by the Catholic Church to eliminate the Cathar heresy in Languedoc.[29][30] Heresy was a major justification for the Inquisition (Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis, Inquiry on Heretical Perversity) and for the European wars of religion associated with the Protestant Reformation.

Galileo Galilei was brought before the Inquisition for heresy, but abjured his views and was sentenced to house arrest, under which he spent the rest of his life. Galileo was found "vehemently suspect of heresy", namely of having held the opinions that the Sun lies motionless at the centre of the universe, that the Earth is not at its centre and moves, and that one may hold and defend an opinion as probable after it has been declared contrary to Holy Scripture. He was required to "abjure, curse and detest" those opinions.[31]

Pope St. Gregory stigmatized Judaism and the Jewish people in many of his writings. He described Jews as enemies of Christ: "The more the Holy Spirit fills the world, the more perverse hatred dominates the souls of the Jews." He labeled all heresy as "Jewish", claiming that Judaism would "pollute [Catholics and] deceive them with sacrilegious seduction."[32] The identification of Jews and heretics in particular occurred several times in Roman-Christian law.[27][33]

Eastern Christianity

In Eastern Christianity heresy most commonly refers to those beliefs declared heretical by the first seven Ecumenical Councils. Since the Great Schism and the Protestant Reformation, various Christian churches have also used the concept in proceedings against individuals and groups those churches deemed heretical. The Orthodox Church also rejects the early Christian heresies such as Arianism, Gnosticism, Origenism, Montanism, Judaizers, Marcionism, Docetism, Adoptionism, Nestorianism, Monophysitism, Monothelitism and Iconoclasm.

Protestantism

In his work "On the Jews and Their Lies" (1543), German Reformation leader Martin Luther claims that Jewish history was "assailed by much heresy", and that Christ the logos swept away the Jewish heresy and goes on to do so, "as it still does daily before our eyes." He stigmatizes Jewish prayer as being "blasphemous" and a lie, and vilifies Jews in general as being spiritually "blind" and "surely possessed by all devils." Luther calls the members of the Catholic Church "papists" and heretics, and has a special spiritual problem with Jewish circumcision.[34]

In England, the 16th-century European Reformation resulted in a number of executions on charges of heresy. During the thirty-eight years of Henry VIII's reign, about sixty heretics, mainly Protestants, were executed and a rather greater number of Catholics lost their lives on grounds of political offences such as treason, notably Sir Thomas More and Cardinal John Fisher, for refusing to accept the king's supremacy over the Church in England.[35][36][37] Under Edward VI, the heresy laws were repealed in 1547 only to be reintroduced in 1554 by Mary I; even so two radicals were executed in Edward's reign (one for denying the reality of the incarnation, the other for denying Christ's divinity).[38] Under Mary, around two hundred and ninety people were burned at the stake between 1555 and 1558 after the restoration of papal jurisdiction.[38] When Elizabeth I came to the throne, the concept of heresy was retained in theory but severely restricted by the 1559 Act of Supremacy and the one hundred and eighty or so Catholics who were executed in the forty-five years of her reign were put to death because they were considered members of "...a subversive fifth column."[39] The last execution of a "heretic" in England occurred under James VI and I in 1612.[40] Although the charge was technically one of "blasphemy" there was one later execution in Scotland (still at that date an entirely independent kingdom) when in 1697 Thomas Aikenhead was accused, among other things, of denying the doctrine of the Trinity.[41]

Another example of the persecution of heretics under Protestant rule was the execution of the Boston martyrs in 1659, 1660, and 1661. These executions resulted from the actions of the Anglican Puritans, who at that time wielded political as well as ecclesiastic control in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. At the time, the colony leaders were apparently hoping to achieve their vision of a "purer absolute theocracy" within their colony . As such, they perceived the teachings and practices of the rival Quaker sect as heretical, even to the point where laws were passed and executions were performed with the aim of ridding their colony of such perceived "heresies". It should be noticed that the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox communions generally regard the Puritans themselves as having been heterodox or heretical.

Modern era

The era of mass persecution and execution of heretics under the banner of Christianity came to an end in 1826 with the last execution of a "heretic", Cayetano Ripoll, by the Catholic Inquisition.

Although less common than in earlier periods, in modern times, formal charges of heresy within Christian churches still occur. Issues in the Protestant churches have included modern biblical criticism and the nature of God. In the Catholic Church, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith criticizes writings for "ambiguities and errors" without using the word "heresy".[42]

Perhaps due to the many modern negative connotations associated with the term heretic, such as the Spanish inquisition, the term is used less often today. The subject of Christian heresy opens up broader questions as to who has a monopoly on spiritual truth, as explored by Jorge Luis Borges in the short story "The Theologians" within the compilation Labyrinths.[43]

Islam

The Baha'i Faith is considered an Islamic heresy in Iran.[44] To Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, Sikhs were heretics.

Ottoman Sultan Selim the Grim, regarded the Shia Qizilbash as heretics, reportedly proclaimed that "the killing of one Shiite had as much otherworldly reward as killing 70 Christians."[45] Shia, in general, have often been accused by Sunnis of being heretics.[46][47][48]

Starting in medieval times, Muslims began to refer to heretics and those who antagonized Islam as zindiqs, the charge being punishable by death.[49]

In some modern day nations and regions, heresy remains an offense punishable by death. One example is the 1989 fatwa issued by the government of Iran, offering a substantial bounty for anyone who succeeds in the assassination of author Salman Rushdie, whose writings were declared as heretical.

Judaism

Orthodox Judaism

Orthodox Judaism considers views on the part of Jews who depart from traditional Jewish principles of faith heretical. In addition, the more right-wing groups within Orthodox Judaism hold that all Jews who reject the simple meaning of Maimonides's 13 principles of Jewish faith are heretics.[50] As such, most of Orthodox Judaism considers Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism heretical movements, and regards most of Conservative Judaism as heretical. The liberal wing of Modern Orthodoxy is more tolerant of Conservative Judaism, particularly its right wing, as there is some theological and practical overlap between these groups.

Other religions

Buddhist literature mentions a wrathful conquest of Buddhist heretics (see Padmasambhava) and the existence of a Buddhist theocracy.[51]

Neo-Confucian heresy has been described.[52]

The act of using Church of Scientology techniques in a form different than originally described by Hubbard is referred to within Scientology as "squirreling" and is said by Scientologists to be high treason.[53] The Religious Technology Center has prosecuted breakaway groups that have practiced Scientology outside the official Church without authorization.

Non-religious usage

The term "heresy" is used not only with regard to religion but also in the context of political theory.[54][55][56]

In other contexts the term does not necessarily have pejorative overtones and may even be complimentary when used, in areas where innovation is welcome, of ideas that are in fundamental disagreement with the status quo in any practice and branch of knowledge. Scientist/author Isaac Asimov considered heresy as an abstraction,[57] Asimov's views are in Forward: The Role of the Heretic. mentioning religious, political, socioeconomic and scientific heresies. He divided scientific heretics into endoheretics (those from within the scientific community) and exoheretics (those from without). Characteristics were ascribed to both and examples of both kinds were offered. Asimov concluded that science orthodoxy defends itself well against endoheretics (by control of science education, grants and publication as examples), but is nearly powerless against exoheretics. He acknowledged by examples that heresy has repeatedly become orthodoxy.

The revisionist paleontologist Robert T. Bakker, who published his findings as The Dinosaur Heresies, treated the mainstream view of dinosaurs as dogma.[58] "I have enormous respect for dinosaur paleontologists past and present. But on average, for the last fifty years, the field hasn't tested dinosaur orthodoxy severely enough." page 27 "Most taxonomists, however, have viewed such new terminology as dangerously destabilizing to the traditional and well-known scheme..." page 462. This book apparently influenced Jurassic Park. The illustrations by the author show dinosaurs in very active poses, in contrast to the traditional perception of lethargy. He is an example of a recent scientific endoheretic.

Immanuel Velikovsky is an example of a recent scientific exoheretic; he did not have appropriate scientific credentials or did not publish in scientific journals. While the details of his work are in scientific disrepute, the concept of catastrophic change (extinction event and punctuated equilibrium) has gained acceptance in recent decades.

The term heresy is also used as an ideological pigeonhole for contemporary writers because, by definition, heresy depends on contrasts with an established orthodoxy. For example, the tongue-in-cheek contemporary usage of heresy, such as to categorize a "Wall Street heresy" a "Democratic heresy" or a "Republican heresy," are metaphors that invariably retain a subtext that links orthodoxies in geology or biology or any other field to religion. These expanded metaphoric senses allude to both the difference between the person's views and the mainstream and the boldness of such a person in propounding these views.

Selected quotations

- Thomas Aquinas: "Wherefore if forgers of money and other evil-doers are forthwith condemned to death by the secular authority, much more reason is there for heretics, as soon as they are convicted of heresy, to be not only excommunicated but even put to death." (Summa Theologica, c. 1270)

- Isaac Asimov: "Science is in a far greater danger from the absence of challenge than from the coming of any number of even absurd challenges."[57]

- Gerald Brenan: "Religions are kept alive by heresies, which are really sudden explosions of faith. Dead religions do not produce them." (Thoughts in a Dry Season, 1978)

- Geoffrey Chaucer: "Thu hast translated the Romance of the Rose, That is a heresy against my law, And maketh wise folk from me withdraw." (The Prologue to The Legend of Good Women, c. 1386)

- G. K. Chesterton: "Truths turn into dogmas the instant that they are disputed. Thus every man who utters a doubt defines a religion." (Heretics, 12th Edition, 1919)

- G. K. Chesterton: "But to have avoided [all heresies] has been one whirling adventure; and in my vision the heavenly chariot flies thundering through the ages, the dull heresies sprawling and prostrate, the wild truth reeling but erect." (Orthodoxy, 1908)

- Benjamin Franklin: "Many a long dispute among divines may be thus abridged: It is so. It is not. It is so. It is not." (Poor Richard's Almanack, 1879)

- Helen Keller: "The heresy of one age becomes the orthodoxy of the next." (Optimism, 1903)

- Lao Tzu: "Those who are intelligent are not ideologues. Those who are ideologues are not intelligent." (Tao Te Ching, Verse 81, 6th century BCE)

- James G. March on the relations among madness, heresy, and genius: "... we sometimes find that such heresies have been the foundation for bold and necessary change, but heresy is usually just new ideas that are foolish or dangerous and appropriately rejected or ignored. So while it may be true that great geniuses are usually heretics, heretics are rarely great geniuses."[59]

- Montesquieu: "No kingdom has ever had as many civil wars as the kingdom of Christ." (Persian Letters, 1721)

- Friedrich Nietzsche: "Whoever has overthrown an existing law of custom has hitherto always first been accounted a bad man: but when, as did happen, the law could not afterwards be reinstated and this fact was accepted, the predicate gradually changed; - history treats almost exclusively of these bad men who subsequently became good men!" (Daybreak, § 20)[60]

See also

Bibliography

- John B. Henderson: The Construction of Orthodoxy and Heresy: Neo-Confucian, Islamic, Jewish, and Early Christian Patterns, SUNY Press 1998.

Notes

- ↑ An "ecclesiastical authority" was initially an assembly of bishops, later the Pope, then an inquisitor (a delegate of the Pope) and later yet the leadership of a Protestant church (which would itself be regarded as heretical by the Pope). The definitions of "state", "cooperation", "suppress" and "heresy" were all subject to change during the past 16 centuries.

- ↑ Only very fragmentary records have been found of the executions carried out under Christian "heresy laws" during the first millennium. Somewhat more complete records of such executions can be found for the second millennium. To estimate the total number of executions carried out under various Christian "heresy laws" from 385 AD until the last official Catholic "heresy execution" in 1826 AD would require far more complete historical documentation than is currently available. The Catholic Church by no means had a monopoly on the execution of heretics. The charge of heresy was a weapon that could fit many hands. A century and a half after heresy was made a state crime, the Vandals(a heretical Christian Germanic tribe), used the law to prosecute thousands of (orthodox) Catholics with penalties of torture, mutilation, slavery and banishment.[22] The Vandals were overthrown; orthodoxy was restored; "No toleration whatsoever was to be granted to heretics or schismatics."[23] Heretics were not the only casualties. 4000 Roman soldiers were killed by heretical peasants in one campaign.[24] Some lists of heretics and heresies are available. About seven thousand people were burned at the stake by the Catholic Inquisition, which lasted for nearly seven centuries.[25] From time to time, heretics were burned at the stake by an enraged local populace, in a certain type of "vigilante justice" , without the official participation of the Church or State.[26] Religious Wars slaughtered millions. During these wars, the charge of "heresy" was often leveled by one side against another as a sort of propaganda or rationalization for the undertaking of such wars.

References

- ↑ "Heresy | Define Heresy at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- ↑ "Apostasy | Learn everything there is to know about Apostasy at". Reference.com. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- ↑ "Definitions of "blasphemy" at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ↑ "heresy - definition of heresy in English from the Oxford dictionary". oxforddictionaries.com.

- ↑ Daryl Glaser, David M. Walker (editors), Twentieth-Century Marxism (Routledge 2007 ISBN 978-1-13597974-4), p. 62

- ↑ Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Heresy". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Bruce, F.F. The Spreading Flame, Exeter: Paternoster 1964, p. 249

- ↑ The NIV Study Bible, Zondervan Corporation, Hodder & Stoughton, London 1987—footnote to Titus 3:10

- ↑ The NIV Study Bible, Zondervan Corporation, Hodder & Stoughton, London 1987—footnote to Titus 1:9

- 1 2 Michael, Robert (2011). A history of Catholic antisemitism : the dark side of the church (1st Palgrave Macmillan pbk. ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-0230111318. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ W.H.C. Frend (1984). The Rise of Christianity. Chapter 7, The Emergence of Orthodoxy 135-93. ISBN 978-0-8006-1931-2. Appendices provide a timeline of Councils, Schisms, Heresies and Persecutions in the years 193-604. They are described in the text.

- ↑ Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Milan, Edict of". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Chadwick, Henry. The Early Christian Church, Pelican 1967, pp 129-30

- ↑ Paul Stephenson (2009). Constantine: Roman Emperor, Christian Victor. Chapter 11. ISBN 978-1-59020-324-8. The Emperor established and enforced orthodoxy for domestic tranquility and the efficacy of prayers in support of the empire.

- ↑ Charles Freeman (2008). A.D. 381 - Heretics, Pagans, and the Dawn of the Monotheistic State. ISBN 978-1-59020-171-8. As Christianity placed its stamp upon the Empire, the Emperor shaped the church for political purposes.

- 1 2 Everett Ferguson (editor), Encyclopedia of Early Christianity (Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-1-13661158-2), p. 950

- ↑ John Anthony McGuckin, The Westminister Handbook to Patristic Theology (Westminster John Knox Press 2004 ISBN 978-0-66422396-0), p. 284

- ↑ "Priscillian". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Chadwick, Henry. The Early Church, Pelican, London, 1967. p.171

- ↑ Jay E. Thompson (1 September 2009). A Tale of Five Cities: A History of the Five Patriarchal Cities of the Early Church. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-4982-7447-0.

- ↑ María Victoria Escribano Paño (2010). "Chapter Three. Heretical texts and maleficium in the Codex Theodosianum (CTh. 16.5.34)". In Richard Lindsay Gordon; Francisco Marco Simón. Magical Practice in the Latin West: Papers from the International Conference Held at the University of Zaragoza, 30 Sept. – 1st Oct. 2005. BRILL. pp. 135–136. ISBN 90-04-17904-6.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon. History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Chapter 37, Part III.

- ↑ W.H.C. Frend (1984). The Rise of Christianity. page 833. ISBN 978-0-8006-1931-2.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon. History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Chapter 21, Part VII.

- ↑ James Carroll (2001). Constantine's Sword. page 357. ISBN 0-618-21908-0.

- ↑ Will & Ariel Durant (1950). The Age of Faith. page 778.

- 1 2 Michael, Robert (2011). A history of Catholic antisemitism : the dark side of the church (1st Palgrave Macmillan pbk. ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 219. ISBN 978-0230111318. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "Massacre of the Pure." Time. April 28, 1961.

- ↑ Joseph Reese Strayer (1992). The Albigensian Crusades. University of Michigan Press. p. 143. ISBN 0-472-06476-2

- ↑ Will & Ariel Durant (1950). The Age of Faith. Chapter XXVIII, The Early Inquisition: 1000-1300.

- ↑ Fantoli (2005, p. 139), Finocchiaro (1989, pp. 288–293).

- ↑ Michael, Robert (2011). A history of Catholic antisemitism : the dark side of the church (1st Palgrave Macmillan pbk. ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 76. ISBN 978-0230111318. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ Constitutio Sirmondiana, 6 + 14; Theodosius II - Novella 3; Codex Theodosianus 16:5:44, 16:8:27, 16:8:27; Codex Justinianus 1:3:54, 1:5:12+21, 1:10:2; Justinian, Novellae 37 + 45

- ↑ Luther, Martin; Rydie, Coleman, ed. (February 18, 2009). On The Jews and Their Lies. lulu.com. ISBN 978-0557050239. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia of Tudor England". google.com.

- ↑ Ron Christenson, Political Trials in History (Transaction Publishers 1991 ISBN 978-0-88738406-6), p. 302

- ↑ Oliver O'Donovan, Joan Lockwood O'Donovan, From Irenaeus to Grotius (Eerdmans 1999 ISBN 978-0-80284209-1), p. 558

- 1 2 Dickens, A.G. The English Reformation Fontana/Collins 1967, p.327/p.364

- ↑ Neill, Stephen. Anglicanism Pelican, pp.96,7

- ↑ MacCullough, Diarmaid. Thomas Cranmer Yale 1996, p.477

- ↑ MacCulloch, Diarmaid. The Reformation Penguin 2003, p. 679

- ↑ An example is the Notification regarding certain writings of Fr. Marciano Vidal, C.Ss.R.

- ↑ Borges, Jorge Luis (1962). Labyrinths. New York: New Directions Publishing Corporation. pp. 119–126. ISBN 978-0-8112-0012-7.

- ↑ Sanasarian, Eliz (2000). Religious Minorities in Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-521-77073-4.

- ↑ Jalāl Āl Aḥmad (1982). Plagued by the West. Translated by Paul Sprachman. Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University. ISBN 978-0-88206-047-7.

- ↑ John Limbert (2009). Negotiating with Iran: Wrestling the Ghosts of History. US Institute of Peace Press. p. 29. ISBN 9781601270436.

- ↑ Masooda Bano (2012). The Rational Believer: Choices and Decisions in the Madrasas of Pakistan. Cornell University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780801464331.

- ↑ Johnson, Thomas A., ed. (2012). Power, National Security, and Transformational Global Events: Challenges Confronting America, China, and Iran (illustrated ed.). CRC Press. p. 162. ISBN 9781439884225.

- ↑ John Bowker. "Zindiq." The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. 1997

- ↑ The Limits of Orthodox Theology: Maimonides' Thirteen Principles Reappraised, by Marc B. Shapiro, ISBN 1-874774-90-0, A book written as a contentious rebuttal to an article written in the Torah u'Maddah Journal.

- ↑ (Buddhism Five precepts)

- ↑ John B. Henderson (1998). The construction of orthodoxy and heresy: Neo-Confucian, Islamic, Jewish, and early Christian patterns. ISBN 978-0-7914-3760-5.

- ↑ Welkos, Robert W.; Sappell, Joel (29 June 1990). "When the Doctrine Leaves the Church". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ "Religion: Anti-Religion". TIME.com. 6 May 1940.

- ↑ Ludwig von Mises, Trotsky's Heresy - Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis

- ↑ "Exploring the high moments and small mountain roads of Marxism". isreview.org.

- 1 2 Donald Goldsmith (1977). Scientists Confront Velikovsky. ISBN 0-8014-0961-6.

- ↑ Robert T. Bakker (1986). The Dinosaur Heresies. ISBN 978-0-8065-2260-9.

- ↑ Coutou, Diane. Ideas as Art. Harvard Business Review 84 (2006): 83–89.

- ↑ Daybreak, R.J. Hollingdale trans., Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 18. Available at http://www.scribd.com/doc/37646181/Nietzsche-Daybreak

External links

| Look up heresy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heresy. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Heresy |

- Some quotes and information in this article came from the Catholic Encyclopedia.

- (French) Cathars of the middle age, Philosophy and History.

- What Is Heresy? by Wilbert R. Gawrisch (Lutheran)