History of Cape Verde

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Cape Verde |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Religion |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Media |

| Sport |

|

Monuments |

|

The recorded history of Cape Verde begins with Portuguese discovery in 1460. Possible early references go back around 2000 years.

Possible classical references

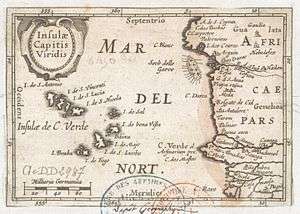

Cape Verde may be referred to in the works "De choreographia" by Pomponius Mela and "Historia naturalis" by Pliny the Elder. They called the islands "Gorgades" in remembering the home of the mythical Gorgons killed by Perseus and afterwards - in typically ancient euhemerism - interpreted (against the written original statement) as the site where the Carthaginian Hanno the Navigator slew two female "Gorillai" and brought their skins into the temple of the female deity Tanit (the Carthaginian Juno) in Carthage.

According to Pliny the Elder, the Greek Xenophon of Lampsacus states that the Gorgades (Cape Verde) are situated two days from "Hesperu Ceras" - today called Cap-Vert, the westernmost part of the African continent. According to Pliny the Elder and his citation by Gaius Julius Solinus, the sea voyage time from Atlantis crossing the Gorgades to the islands of the Ladies of the West (Hesperides) is around 40 days.

The Isles of the Blessed written of by Marinos of Tyre and referenced by Ptolemy in his Geographia may have been the Cape Verde islands.[1]

Possible visits from Africa

The Portuguese explorers discovered the islands in 1456 and described the islands as uninhabited. However, given the prevailing winds and ocean currents in the region, the islands may well have been visited by Moors or Wolof, Serer, or perhaps Lebou fishermen from the Guinea (region) coast.

Folklore suggests that the islands may have been visited by Arabs, centuries before the arrival of the Europeans. The Portuguese writer and historian Jaime Cortesão (1884—1960) reported a story that Arabs were known to have visited an island which they referred to as "Aulil" or "Ulil" where they took salt from naturally occurring salinas. Some believe they may have been referring to Sal Island.

European discovery and settlement

In 1456, at the service of prince Henry the Navigator, Alvise Cadamosto, Antoniotto Usodimare (a Venetian and a Genoese captains, respectively) and an unnamed Portuguese captain, jointly discovered some of the islands. In the next decade, Diogo Gomes and António de Noli, also captains in the service of prince Henry, discovered the remaining islands of the archipelago. When these mariners first landed in Cape Verde, the islands were barren of people but not of vegetation. The Portuguese returned six years later to the island of São Tiago to found Ribeira Grande (now Cidade Velha), in 1462—the first permanent European settlement city in the tropics.

In Spain the Reconquista movement was growing in its mission to recover Catholic lands from the Muslim Moors who had first arrived as conquerors in the 8th century. In 1492 the Spanish Inquisition also emerged in its fullest expression of anti-Semitism. It spread to neighboring Portugal where King João II and especially Manuel I in 1496, decided to exile thousands of Jews to São Tomé, Príncipe, and Cape Verde.

The Portuguese soon brought slaves from the West African coast. Positioned on the great trade routes between Africa, Europe, and the New World, the archipelago prospered from the transatlantic slave trade, in the 16th century.

The islands' prosperity brought them unwanted attention in the form of a sacking at the hands of many pirates including England's Sir Francis Drake, who in 1582 and 1585 sacked Ribeira Grande. After a French attack in 1712, the city declined in importance relative to Praia, which became the capital in 1770.

Colonial Period

Droughts and famines

In 1747 the islands were hit with the first of the many droughts that have plagued them ever since, with an average interval of five years. The situation was made worse by deforestation and overgrazing, which destroyed the ground vegetation that provided moisture. Three major droughts in the 18th and 19th centuries resulted in well over 100,000 people starving to death. The Portuguese government sent almost no relief during any of the droughts.

Abolition of the slave trade

The 19th-century decline of the lucrative slave trade was another blow to the country's economy. The fragile prosperity slowly vanished. Cape Verde's colonial heyday was over.

Emigration to USA

It was around this time that Cape Verdeans started emigrating to New England. This was a popular destination because of the whales that abounded in the waters around Cape Verde, and as early as 1810 whaling ships from Massachusetts and Rhode Island in the United States (U.S.) recruited crews from the islands of Brava and Fogo.

Mindelo's Harbour

At the end of the 19th century, with the advent of the ocean liner, the island's position astride Atlantic shipping lanes made Cape Verde an ideal location for resupplying ships with fuel (imported coal), water and livestock. Because of its excellent harbour, Mindelo (on the island of São Vicente) became an important commercial centre during the 19th century, mainly because the British used Cape Verde as a storage depot for coal which was bound for the Americas. The harbour area at Mindelo was developed by the British for this purpose.

The island was made a coaling and submarine cable station, and there was plenty of work for local labourers. This was the golden period of the city, where it gained the cultural characteristics that made it the current cultural capital of the country. During World War II, the economy collapsed as the shipping traffic was drastically reduced. As the British coal industry went into decline in the 1980s, this source of income dried up, and Britain had to abandon its Cape Verdean interests — which ended up being the final strike to the highly dependent local economy.

Independence movement

Although the Cape Verdeans were treated badly by their colonial masters, they fared slightly better than Africans in other Portuguese colonies because of their lighter skin. A small minority received an education and Cape Verde was the first African-Portuguese colony to have a school for higher education. By the time of independence, a quarter of the population could read, compared to 5% in Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau).

This largesse ultimately backfired on the Portuguese, however, as literate Cape Verdeans became aware of the pressures for independence building on the mainland, while the islands continued suffering from frequent drought and famine, at times from epidemic diseases and volcanic eruptions, and the Portuguese government did nothing. Thousands of people died of starvation during the first half of the 20th century. Although the nationalist movement appeared less fervent in Cape Verde than in Portugal's other African holdings, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC, acronym for the Portuguese Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde) was founded in 1956 by Amílcar Cabral and other pan-Africanists, and many Cape Verdeans fought for independence in Guinea-Bissau.[2]

In 1926 Portugal had become a rightist dictatorship which regarded the colonies as an economic frontier, to be developed in the interest of Portugal and the Portuguese. Frequent famine, unemployment, poverty and the failure of the Portuguese government to address these issues caused resentment. The Portuguese dictator António de Oliveira Salazar wasn't about to give up his colonies as easily as the British and French had given up theirs.

After World War II, Portugal was intent to hold on to its former colonies, since 1951 called overseas territories. When most former African colonies gained independence in 1957/1964, the Portuguese still held on. Consequently, following the Pijiguiti Massacre, the people of Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau fought one of the longest African liberation wars.

After the fall (April 1974) of the regime in Portugal, widespread unrest forced the government to negotiate with the PAIGC, and on July 5, 1975, Cape Verde gained independence from Portugal.

Post-Independence (1975)

.svg.png)

Immediately following a November 1980 coup in Guinea-Bissau (Portuguese Guinea declared independence in 1973 and was granted de jure independence in 1974), relations between the two countries became strained. Cape Verde abandoned its hope for unity with Guinea-Bissau and formed the African Party for the Independence of Cape Verde (PAICV). Problems have since been resolved, and relations between the countries are good. The PAICV and its predecessor established a one-party state and ruled Cape Verde from independence until 1990.

Responding to growing pressure for a political opening, the PAICV called an emergency congress in February 1990 to discuss proposed constitutional changes to end one-party rule. Opposition groups came together to form the Movement for Democracy (MpD) in Praia in April 1990. Together, they campaigned for the right to contest the presidential election scheduled for December 1990. The one-party state was abolished September 28, 1990, and the first multi-party elections were held in January 1991.

The MpD won a majority of the seats in the National Assembly, and the MpD presidential candidate António Mascarenhas Monteiro defeated the PAICV's candidate by 73.5% of the votes cast to 26.5%. He succeeded the country's first President, Aristides Pereira, who had served since 1975.

Legislative elections in December 1995 increased the MpD majority in the National Assembly. The party held 50 of the National Assembly's 72 seats. A February 1996 presidential election returned President António Mascarenhas Monteiro to office. The December 1995 and February 1996 elections were judged free and fair by domestic and international observers.

In the presidential election campaign of 2000 and 2001, two former prime ministers, Pedro Pires and Carlos Veiga were the main candidates. Pires was the Prime Minister during the PAICV regime, while Veiga served as prime minister during most of Monteiro's presidency, stepping aside only when it came time for campaigning. In what might have been one of the closest races in electoral history, Pires won by 12 votes, he and Veiga each receiving nearly half the votes.

See also

- History of Africa

- History of Guinea-Bissau

- History of West Africa

- List of heads of government of Cape Verde

- List of heads of state of Cape Verde

- Politics of Cape Verde

Footnotes

- ↑ Analysis of Ptolemy's Geographia

- ↑ See, for instance, Kevin Shillington, History of Africa, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 1989, p. 399.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Cape Verde. |

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "São Thiago de Cabo Verde". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "São Thiago de Cabo Verde". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Cape Verde Historical Timeline by Raymond Almeida. alternative site