History of the Pittsburgh Steelers

This article details the history of the Pittsburgh Steelers. The Steelers are an American football franchise representing Pittsburgh. They are the seventh-oldest club in the National Football League (NFL), which they joined in 1933.[1] The only surviving NFL teams with a longer history are the Chicago Bears, Chicago (Arizona as well as St. Louis) Cardinals, Detroit Lions (then the Portsmouth Spartans), Green Bay Packers, New York Giants and Boston (Washington) Redskins. The Philadelphia Eagles joined the league concurrently with the Steelers in 1933.

The team was founded by Arthur J. "Art" Rooney. The Rooney family has held a controlling interest in the club for almost its entire history. Since its founding the team has captured six league championships and competed in more than a thousand games. In 2008 the Steelers became the first NFL team to capture six Super Bowl titles. Currently the club is fourth in total NFL Championships behind the Packers (13), Bears (9), and Giants (8). Eighteen Steelers players, coaches or administrators have been enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.[2]

Precursors

Art Rooney, who was born and raised in the Pittsburgh area, was an exceptional all-around athlete.[3] Rooney was recruited to play football for Notre Dame, baseball for the Boston Red Sox;[3] and invited to join the 1920 Olympic boxing team.[4] His love of sports would lead to him becoming an organizer and promoter. This included the Hope-Harvey Football Club, a semi-professional American football team which he founded as a teenager.[5] "In a way, I guess that was the start of the Steelers. It grew from that", Rooney said.[5]

The name "Hope-Harvey" was derived from the Hope Fire House, located in the heart of the Pittsburgh's North Side, which served as the team's locker room, and Dr. Harvey, a local physician, who was a sponsor and unofficial team doctor.[6] The Hope-Harvey Majestics competed against other semi-pro or "sandlot" teams; a collection would be raised from the fans in attendance which would be split amongst the players. In addition to being the team's manager and coach, Art Rooney at times played quarterback for the team, which also included his younger brothers, Dan and Jim.[6] Behind the Rooney boys, these teams met a fair amount of success, including at least two Western Pennsylvania Senior Independent Football Conference titles in the early 1930s.[7]

The Hope-Harvey club, which would later come to be known as "Majestic Radio" (when they gained a sponsor) and later the "James P. Rooneys" (to promote the state legislative campaign of the team's quarterback, and Art Rooney's brother, Jimmy Rooney),[8] played most of their home games at Exposition Park in Pittsburgh.[5] These Steeler precursors were composed primarily of players from the local colleges: Pitt, Duquesne and Carnegie Tech, all of which were major college programs of the day.[8]

Although football was popular in Pittsburgh at the time, the city had no fully professional teams due to Pennsylvania's puritanical blue laws, which prohibited athletic competition on Sundays because it was the Sabbath.[5] The teams of the National Football League, which was founded in 1920, played primarily on Sunday to avoid conflicts with college football games which were played on Saturday.

The early years: Decades of futility

In May 1933, in anticipation of the repeal of some of Pennsylvania's restrictive laws in the fall of that year, Rooney applied for a franchise with the NFL.[9] His request was granted on May 19, 1933, and the Pittsburgh Professional Football Club, Inc. joined the NFL in exchange for a US$2,500 franchise fee (roughly $46,000 in today's dollars).[10] The new team was known as the Pirates in reference to their baseball club landlords at Forbes Field. Before settling on Forbes, Rooney considered playing at Greenlee Field, which housed the city's Negro League baseball club.[11] Since the blue laws were not repealed until November's general election, the team was forced to play its first four home games on Wednesday nights.[8]

Over the course of the next four decades, Rooney's new team was a study in frustration. They posted a winning record only eight times in their first 39 NFL seasons and never sniffed a championship.[8]

The 1930s: The Pirates years

.jpg)

In the early years of the franchise, the Pirates were not Rooney's only (or even his primary) focus. Even the office off the lobby of the Fort Pitt Hotel from which he ran the team was shared with the Rooney-McGinley Boxing Club, which promoted fights.[12][13] He also spent a good amount of his time and energy handicapping and placing bets on horse racing, a lifelong hobby. Rooney once won an estimated $250,000 to $300,000 ($4.4 to $5.3 million today) in a single 1936 day of betting.[14] It actually was highly likely that the purchase of the Pittsburgh Steelers was made with horse race gamblings. However, this is becoming an urban legend with the NFL trying to clear their name of such shady early beginnings.[15]

What can safely be said is that Rooney's gambling winnings did help keep the football franchise afloat,[8] because while Rooney fared well off the field, the Pirates struggled on it. Rooney said of those lean years, "In those days, nobody got wealthy in sports. You had two thrills. One came Sunday, trying to win the game. The next came Monday, trying to make the payroll."[16]

Although he strove to field a winning team, Rooney spent a good deal of energy simply trying to keep the franchise in business through its early seasons.[17] During the 1930s, while America was in the depths of the Great Depression, the Pirates were a financial drain on Rooney. Rooney claimed that the team lost nearly $10,000 in 1934 ($177,189 today).[18] Bidding wars for players made it difficult for less established clubs to compete with the more seasoned Giants, Bears and Packers. In 1935, Rooney proposed a restriction on the number of players that could be signed by teams that finished at the top of the league.[18] These ideas eventually lead to the creation of the NFL Draft, which first came into being in 1936.

The Pirates' first uniforms were gold with black stripes and were adorned with the city crest. This color scheme was inspired by Pittsburgh's city flag.[19] The stripes were created with felt overlays, and as such they had functional as well as aesthetic value in that they allowed the ball carrier to hold the ball more securely.[20]

Rooney hired Forrest "Jap" Douds as player-coach.[5] Douds was a three-time All-American and local legend as a player at Washington & Jefferson College,[21] and had been an All-Pro in the NFL.[22] Pittsburgh's inaugural game, against the New York Giants was a 23–2 defeat[23] in front of a crowd of about 20,000.[8] The franchise's first ever points came off a safety which resulted when Pirates center John "Cap" Oehler blocked a punt through the end zone.[24] Rooney wrote of the game, "The Giants won. Our team looks terrible. The fans didn't get their money's worth."[25]

The Pittsburgh Pirates notched their first victory a week later, defeating the Chicago Cardinals[23] 14–13, in front of about 5,000 fans.[8] The team scored its first ever touchdown when Martin "Butch" Kottler returned an interception 99 yards. The other hero that day was Mose Kelsch, who at 36 years of age was the oldest player in the NFL – four years older even than team owner Rooney. Kelsch, a holdover from the sandlot Majestics, kicked the extra point that was the margin of victory.[19]

In their sixth game the Pirates set an NFL record the franchise still shares by combining with the Cincinnati Reds to punt 31 times in a scoreless tie. The Bears and Packers matched the mark in a game played on the same day, but it has never been surpassed.[19]

The total attendance for their five home games in the inaugural season was around 57,000. To put that number into perspective, that year's Pitt-Duquesne college matchup was watched by around 60,000 fans.[19] The team finished their initial season with a 3–6–2 record,[26] after which Coach Douds was not retained as coach, though he stayed with the team two more years as a player.[27]

Rooney pursued Heartley "Hunk" Anderson, who had recently stepped down as head coach at Notre Dame, to replace Douds.[28] After being rebuffed by Anderson in favor of a similar position at North Carolina State,[29] Rooney went after Earle "Greasy" Neale.[30] It speaks to the stature of the professional game relative to college football that Neale turned down the Pirates' offer in order to take an assistant coaching position at Yale University.[31] Neale would later coach the Philadelphia Eagles to two NFL championships and earn a spot in the Hall of Fame.[32]

Luby DiMeolo, who had been rumored as the leading candidate for the Pirates coaching job prior to the team's first season,[33] was eventually hired to replace Douds. He had been captain of the 1929 Pittsburgh Panthers football team on which Jimmy Rooney also starred. DiMeolo hired Jimmy Rooney as an assistant.[34] Following a disappointing 2–10 season in 1934, DiMeolo was dismissed.

Rooney attempted to lure football legend Red Grange, who had just retired as a player, to coach the team the following year.[24] Grange eventually declined the offer in favor of an assistant coaching position with the Chicago Bears.[35] Rooney settled instead on Duquesne coach Joe Bach.[36] Bach was notable as one of Notre Dame's "seven mules", who blocked for the team's famed "Four Horsemen". In Bach's first season the team improved on the previous years two wins, but they still were not very competitive at 4–8.

1936 saw the institution of the National Football League draft as a means of distributing talent more equitably amongst teams. The Pirates saw little initial return, however, as the team's first draft pick, William Shakespeare, would never play in the NFL.[37] The franchise would trade their first round pick multiple times in their first 30 years.

In his second season with the Pirates in 1936, Bach had his team in contention for the NFL's Eastern Division title with a 6–3 record through nine games. However, the season fell apart with losses in the final three games. Rooney and Bach each blamed the other for the collapse. Although Rooney and Bach had an agreement for Bach to remain with the club in 1937, Bach decided instead to take the head job at Niagara University, for which Rooney released him from his verbal commitment.[38] Rooney later expressed regret for letting Bach leave.[39]

The Bach era (such as it was) gave way to that of Johnny "Blood" McNally who took over as player-coach in 1937. McNally was an eleven-year NFL veteran who had played for the Pirates in 1934. He was one of the game's most colorful characters,[40] and Rooney hired him with an eye toward increasing ticket sales.[41] After a 2–0 start, the team lost its next five games, finishing at 4–7.

The next season saw the arrival of the franchise's first superstar, Byron "Whizzer" White. The Pirates selected White, the All-America quarterback from the University of Colorado, with the fourth overall selection of the 1938 NFL Draft and offered him an unheard of salary of $15,000 (around $250,000 today) to join the team. White declined the generous offer, in order to continue his education through a Rhodes Scholarship at Oxford University.[42] However, when he was able to arrange to defer his start at Oxford until January, he reconsidered and signed the deal.[43] In addition to the league-high salary,[44] the terms of the deal also included a share of the gate at exhibition games for White,[45] who earned a total of $15,800 (around $270,000 today).[46] In comparison, McNally who served as both coach and player earned just $3,500 (roughly $59,000 today).[44] The big contract Rooney gave White angered several of his fellow owners.[44]

The arrival of White led to much optimism in Pittsburgh – McNally stated that, "We had calculated on a championship without him, and since we have him it looks like we can't miss."[47] White did not disappoint: he led the league in rushing with 567 yards on 152 attempts.[48] However, the team was unable to capitalize on White's performance compiling a record of just two wins against nine losses, including a season-ending string of six straight defeats. After the season, White sailed on to England and never again played for the Pirates. White would go on to become one of the longest serving justices in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court.[49]

After seeing the disappointing results of paying big money for a star player, in 1938 Rooney determined to pursue a star coach. He offered the head coaching job to Jock Sutherland, who was a legendary football coach and "national hero".[50] Sutherland had just stepped down as head coach at the University of Pittsburgh. The offer was to have been in excess of the $13,000 annual salary (roughly $220,000 today) Sutherland earned at Pitt. When Sutherland spurned the offer (due most likely to the disdain in which he held the professional game)[51] McNally was retained as the Pirates' coach, although he announced his retirement as a player.[52]

The 1939 season started just as the previous season had ended: with a string of losses. After the third straight loss (which stretched the two season run of failure to nine games), McNally resigned as coach.[53] Despite compiling a coaching record with the Pirates of just 6–19, Johnny "Blood" McNally would enter the Hall of Fame in 1963.[54]

McNally was replaced by Walt Kiesling, who had been McNally's assistant coach for the previous two seasons.[55] Their seventh season less than half played, the Pirates had just hired their fifth head coach. Kiesling was unable to salvage the season; the team ended 1939 with a worst yet mark of 1–9–1. The season's lone win came in the season's final game against the Philadelphia Eagles, with whom the Steelers shared the league cellar – the Eagles compiled an identical 1–9–1 record with their season's sole bright spot being an earlier triumph over the Steelers. The victory broke a winless streak that had extended to nearly fourteen months.[56]

Through the 1930s the Pirates never finished higher than second place in their division, or with a record better than .500.

1940–41: A new name and a "new" team

In early 1940, Rooney decided that he had had enough of the copycat Pirates moniker. He worked with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette to run a contest to find a new name for the team.[57] Former coach Joe Bach led the panel which selected the name Steelers from amongst the entries.[58] The new name paid homage to the city's largest industry of producing steel.[4]

It's unclear who deserves credit for suggesting the name (which was already being used by at least one local high school team),[59] but it appears there were a total of twenty-one "winners". Each winner received a pair of season tickets to the upcoming season, a prize with a value of about $5 ($85 today).[58] Among them were Joe Santoni, a local restaurateur, who received a pair of season tickets as a prize,[60] and Margaret Elizabeth O'Donnell, the girlfriend (and eventual wife) of the team's business manager, Joe Carr.[61] The first entrant who suggested "Steelers" was Arnold Goldberg, who was sports editor for the Evening Standard of Uniontown, Pennsylvania. Other suggestions were Wahoos, Condors, Pioneers, Triangles, Bridgers, Buckaroos and Yankees, along with such steel-centric possibilities as the Millers, Vulcans, Tubers, Smokers, Rollers, Ingots and Puddlers.[58]

Kiesling continued as coach in 1940. The Steelers started the season at 1–0–2 before falling at home by a score of 10–3 to a Brooklyn Dodgers squad coached by local hero Jock Sutherland. It was the legendary coach's first professional victory after leaving Duquesne University in 1939. He had assumed the head job for the Dodgers that year after spurning a similar offer from the Pirates/Steelers the previous season.[62] The loss to the Dodgers began a six-game losing streak, before the team traded wins with the Philadelphia Eagles to cap a 2–7–2 season in which they scored a total of just 60 points.[57]

Rooney had finally seen enough. Over eight years, the team had compiled a record of 24–62–5 and had lost around $100,000 ($1.7 million today).[57] He was also concerned about the availability of players in the coming seasons due to the ongoing war in Europe and the specter of a military draft.[63] After turning down several earlier offers to relocate or sell the team,[64] in December 1940, Rooney sold the Steelers to Alexis Thompson.[65] Thompson was a 26-year-old, Yale-educated heir to a steel fortune and an entrepreneur living in New York.[66] He had aggressively pursued Rooney to sell the franchise for several months prior to the transaction.[63] The purchase price was reported to be $160,000 ($2.7 million today).[67] This price is less than the $225,000 ($3.8 million today) the Detroit Lions had previously sold for, but the Lions had won an NFL championship.[64] The transaction was completed and announced on the same day that the Chicago Bears pummeled the Washington Redskins by a score of 73–0 in the most lopsided NFL championship game of all time.[68]

Rooney immediately took half of the windfall and invested it in a 50% interest in the Philadelphia Eagles, which were owned by his friend, Bert Bell. It was Bell who had conducted all of the negotiations with Thompson leading up to the sale of the Steelers. Thompson had earlier offered to purchase Bell's franchise.[69]

In an unusual twist Rooney, Bell and Thompson pooled the rosters of the two squads and conducted essentially a mini-draft to distribute the talent. The 51 players which were signed to the Steelers and Eagles at the end of the 1940 season were shuffled between the two teams.[70] In this transaction, the Rooney/Bell team added eleven players from the 1940 Steelers: ends George Platukis, Walt Kichefski and John Klumb; tackles Clark Goff and Ted Doyle; guards Carl Nery and Jack Sanders; and backs Boyd Brumbaugh, John Noppenberg, George Kiick and Rocco Pirro. In exchange, Thompson's team gained seven players: ends Joe Carter and Herschel Ramsey, tackles Phil Ragazzo and Clem Woltman, guard Ted Schmitt, and backs Joe Bukant and Foster Watkins, all of whom had played for Bell's 1940 Eagles the prior year.[71][58]

Thompson hired Greasy Neale, whom Rooney had earlier pursued to coach the Pirates, to conduct this player swap as well as to assist him with the draft which took place the day after the deal with Rooney was finalized.[66] Once he was released from his contract with Yale, Neale became head coach of Thompson's team.[72] In January 1941, Thompson renamed his new squad the Iron Men.[73]

Despite the fact he now was half-owner of a team in based Philadelphia, Rooney had no intention of leaving Pittsburgh.[69] It was thought that Thompson preferred to move his new team to be nearer his New York home, perhaps to Boston, which had been without an NFL team since the Redskins relocated to Washington in 1937.[65] If Thompson had moved the team away from Pittsburgh, Rooney and Bell hatched a plan that would have seen their team split its home games between the two Pennsylvania cities. However, the other league owners blocked both moves.[74]

By early 1941, Rooney was beginning to regret his decision to sell the Pittsburgh team. When he saw that Thompson had not yet established a local office for his team, as he had announced he would do by March 1, Rooney made an offer. He and Bell would trade territories with Thompson. This would put Thompson in Philadelphia, which was much closer to his New York base. It would also ensure that Rooney's team would stay in his hometown. On April 3, 1941, Thompson accepted the deal and Rooney and Bell's Eagles went to Pittsburgh, where they became the Steelers, while Thompson's Iron Men moved to Philadelphia, where they took on the Eagles moniker. This was described at the time as "one of the most unusual swaps in sports history".[75] In fact, though the Pittsburgh team played as the Steelers, they operated under the name the "Philadelphia Eagles Football Club, Inc." for the next several years.[76][77]

Because the entire strange turn of events all took place during the off-season and the Steelers never actually missed a game in Pittsburgh, the NFL considers the Rooney reign unbroken.[76] The transaction, which amounted in the end to Bell selling the Eagles and purchasing half-interest in the Steelers, has been termed the "Pennsylvania Polka".[78]

1941–44: The war years

Rooney and Bell conducted a coaching search seeking "one of the top men of the profession."[79] Among the men interviewed was Pete Cawthon who had recently left Texas Tech after a successful 12-year stint.[80] Bell and Rooney also considered Aldo "Buff" Donelli, who was the head man for Duquesne University's football team.[81]

In the end, Bell, who had coached the Eagles to five straight losing seasons, named himself head coach of the team. This move was made in part because the owners were hesitant to offer a binding contract to a coach due to the specter of the country possibly entering the war.[81] Kiesling, who had led the Steelers the previous season, was retained as Bell's assistant.[82] The Steelers began the 1941 season with two straight losses, after which Rooney tried to convince Bell to step down as coach. Bell agreed to do so only if Rooney could convince Buff Donelli to take over the reins.[80][83]

Donelli, however, already held the head coaching position at Duquesne University, for which he was under contract for another full season. Donelli and Rooney worked out a deal with the Duquesne administrators whereby Donelli retained his position as head coach at Duquesne, with the intent of coaching the Steelers in his "spare moments".[84] He would accomplish this by coaching the pro team in the morning and the college team in the afternoon; he would spend Saturday on the sidelines for the Dukes and Sunday with the Steelers.[85]

This was a highly unusual situation, and it did not sit well with new NFL commissioner Elmer Layden (for whom Donelli had played when Layden was the coach at Duquesne).[85] Layden was convinced that it was "impossible, physically and mentally, to direct two major football teams at the same time."[86] Donelli stepped down as coach at Duquesne to assuage Layden.[86] However, he retained the title of athletic director at the school and his schedule changed little, if at all. He continued to attend all of Duquesne's practices and games and continued to be acknowledged as the coach, if not in title.[87][88]

Donelli replaced the single-wing offense the Steelers had employed since their founding with his "wing-T", which was a variation on the T formation.[89][90] He coached the Steelers to five straight losses, even while his college team flourished. In early November Donelli faced a dilemma: Duquesne was scheduled to play Saint Mary's College of California on the same weekend the Steelers had a contest in Philadelphia. Layden ordered Donelli to appear on the sidelines in Philly. Donelli chose to stick with the undefeated college squad, and stepped down as head coach of the winless Steelers.[87][91]

The Steelers' coaching position was once more handed over to Kiesling. In Kiesling's second game of this second stint as the Steelers' leader, he led the team to a victory over Jock Sutherland's Brooklyn Dodgers. This would be the only victory in a 1–9–1 season, which matched the team's worst record to date. In a small bright spot, this was the franchise's first campaign in which they were never shut out.[92]

Perhaps the most enduring event of the 1941 season was an off-hand remark that Rooney made to a reporter during the team's training camp. Rooney was visiting camp and quipped to a reporter, "They look like the Steelers to me—in green jerseys."[93] This was taken as a reference to the club's poor performance throughout its existence. The remark would morph into the slogan "Same Old Steelers,"[94] which would be applied by fans as a sort of unofficial team motto throughout the team's consistent struggles over the subsequent thirty years.[95]

Within weeks of the end of the 1941 season, America would enter World War II, which would have a huge impact on the nation, but also on the NFL and its teams. Although the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 had instituted conscription in late 1940, the NFL was not significantly impacted until after the United States joined the war following Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941.

Rooney and Bell lobbied to delay the 1942 NFL Draft due to the uncertainty of the war situation, but they were overruled by their fellow owners. The Steelers had the first overall selection, due to their last-place showing the previous season. They made Virginia halfback "Bullet" Bill Dudley the first pick. They then rounded out the draft by choosing as many married players as possible with an eye toward the likelihood those players could avoid the military draft, at least for the upcoming season.[96][97]

The team lost several players who had filled key roles the previous year to the military, including quarterbacks Johnny Patrick and Rocco Pirro, leading runner Art Jones and budding tackle Joe Coomer.[98] The team's first-round pick, Bill Dudley, intended as well to join the military rather than play football, but when he enlisted in September 1942 there was such a backlog of recruits that his induction was delayed by a few months. This gave him the opportunity to sign with the Steelers for $5,000 ($72,536 today).[99]

After a slow start, in which they lost their first two games, the 1942 squad then won seven of their next eight contests.[100] They fell to the Green Bay Packers in their final game to cap a 7–4 season. They finished in second place in the Eastern Division behind the Washington Redskins, who went on to capture the league title. It was the first winning record the club had recorded in its ten-year history.[99] Dudley became the second Steeler to lead the league in rushing with 696 yards on 162 attempts.[101] The "triple-threat" back also tallied 35 passes for 438 yards and 18 punts and was runner-up to Green Bay's Don Hutson for the Joe F. Carr Trophy which is awarded to the league's most valuable player.[102]

Steagles

At the annual league meeting held on the weekend of the 1942 NFL Championship Game, the league's owners discussed canceling the upcoming 1943 season due to concerns of player availability due to the war. Instead they chose to delay the decision, along with the college draft, until the following April.[103] At the April meeting roster sizes were reduced from 33 to 25 players. Additionally, the Cleveland Rams announced that they would suspend operations for the season since the team's two top executives were serving in the military.[104]

The Steelers' roster continued to be decimated throughout the off-season. By late May, they were down to just five players under contract who would be available to play in the upcoming season. Rooney and Bell reached out to Alexis Thompson's Philadelphia Eagles to discuss the possibility of combining the two squads.[105] A proposal to combine was submitted to the league and was slated for discussion at league meetings in mid-June.[106] At the confab the Chicago Bears and Chicago Cardinals sprung a similar request of their own. The league owners voted down the two mergers on the basis that by combining resources the merged clubs would gain an unfair advantage. Rooney and Bell then lobbied the Chicago clubs to withdraw their request, which they eventually agreed to do. After a contentious debate the owners then voted by a narrow 5–4 margin to allow the Steelers and Eagles to merge operations for the upcoming season and retain their players thereafter.[107]

Although the combined team was officially the Eagles and would have no city designation, it became known familiarly as the Phil-Pitt "Steagles". The club split its home dates between the two cities with four games played in Philadelphia and two in Pittsburgh. Walt Kiesling shared coaching duties with Eagles coach Greasy Neale[107] and the club adopted the T formation which had been used very effectively by the Chicago Bears for the past several seasons. Many of the Steagles players were classified 4-F by the Selective Service, meaning they were judged as unfit for military service.[108] Common ailments were ulcers, perforated eardrums and poor eyesight or hearing.[109]

Co-coaches Neale and Kiesling disliked each other immensely. In order to avoid coaching together, they split coaching responsibility along the lines of offense and defense. This accommodation presaged the rise of the modern offensive and defensive coordinator positions that are near universal in the modern game.[108]

The team ended the season with a 5–4–1 record which was the first winning record in the Eagles' history and just second the Steelers had enjoyed. They missed the playoffs and disbanded into separate franchises immediately upon the season's end.

Card-Pitt

In 1944 they merged with the Chicago Cardinals and were known as "Card-Pitt" and informally known as the "Car-Pitts" or "Carpets." They went winless through the season. The Steelers went solo again for the 1945 season and went 2–8. Dudley was back from the war by the 1946 season and became league MVP. The rest of team did no better as the Steelers stumbled down the stretch and finished 5–5–1.

The 1940s and '50s: "Same Old Steelers"

The Steelers made the playoffs for the first time in 1947, tying for first place in the division at 8–4 with the Philadelphia Eagles. This forced a tie-breaking playoff game at Forbes Field, which the Steelers lost 21–0. Because of the Steelers and Eagles being placed in different conferences after the 1970 merger between the NFL and the AFL, the game marks the only time that the two major Pennsylvania cities have played each other in the NFL playoffs. Quarterback Johnny Clement actually finished second in the league in rushing yardage with 670.

That would be Pittsburgh's last playoff game for 25 years. In the 1948 off season, coach Jock Sutherland died. The team struggled through the season (one quarterback, Ray Evans, threw 17 interceptions to only five touchdowns) and finished 4–8. The team once again faded down the stretch in 1949 after a strong start, ending with a 6–5–1 record. That was followed up in 1950 with a 6–6 season, and consecutive losing seasons in 1951 (4–7–1) and 1952 (5–7).

After a 6–6 season in 1953 and 5–7 season in 1954, the Steelers drafted Johnny Unitas in 1955. Cut by the Steelers in training camp, Unitas later resurfaced as a Super Bowl hero – with the Baltimore Colts. Pittsburgh suffered through yet two more losing seasons before a 6–6 campaign in 1957 in the first season for coach Buddy Parker. 1957 saw one other highlight, the hiring of the NFL's first African American coach, Lowell Perry as the Steelers receivers coach.

Early in the 1958 season the Steelers traded for quarterback Bobby Layne, who led the Detroit Lions to two NFL championships. The results were immediate, with the Steelers posting a winning record (7–4–1) for the first time in nine years – though they were still two games out of a playoff spot. 1958 also saw the first Steelers home games at Pitt Stadium, although their primary venue continued to be Forbes Field.

The Steelers finished above .500 again with a 6–5–1 record in 1959. After a 5–6–1 season in 1960, Rudy Bukich took over the starting QB job during the 1961 season, but fared no better. Pittsburgh finished 6–8.

The 1960s

The Steelers introduced the famous "astroid" logo, based on that of the Steelmark used by the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI), in time for the 1962 season. Bobby Layne returned to the full-time starting quarterback position, and running back John Henry Johnson had the best season of his career with 1,141 yards (second in the NFL). Pittsburgh shored up on defense too, picking up Clendon Thomas from the Los Angeles Rams; he led the team with seven interceptions. Ernie Stautner anchored the defensive line. The Steelers had their best season yet, finishing 9–5. This was good for second place in the division, and a spot in the Playoff Bowl, which matched up the No. 2 teams in the NFL's two divisions. The Steelers lost that game, 17–10, to the Detroit Lions.

Ed Brown became quarterback in time for the 1963 season after Layne retired. Pittsburgh finished 7–4–3, but in a hotly contested Eastern Division, that only allowed the Steelers a 4th-place showing. Ernie Stautner retired after the season. 1963 also resulted in a change of venue for the Steelers, who split their home schedule between Forbes Field and Pitt Stadium, moving exclusively to Pitt in 1964.

The next few years were total disasters for the Steelers. Another 1,000-yard season for John Henry Johnson was the only bright spot in a lackluster 1964 season that ended in a 5–9 record. Another retirement stung the team, this one of coach Buddy Parker. The wheels totally fell off in 1965, when the team finished at a league-worst 2–12. Over the next four years, the Steelers never finished higher than 5–8–1 (1966), with the team using eight quarterbacks between 1965 and 1969.

Indicative of the Steelers' struggles is the fact that Western Pennsylvania has long been an area producing fine quarterbacks, but the Steelers had never managed to keep them. Unitas was a native of Pittsburgh, making his later success even more jarring to Steeler fans. George Blanda came from the Pittsburgh area, but the Steelers never signed him. The nearby town of Beaver Falls produced Babe Parilli and later Joe Namath, who became stars in the American Football League. The Steelers never signed the Beaver Falls natives, either. They did sign another future Hall-of-Famer, Ohio native Len Dawson, but would let him go as well, before he began a great career with the Kansas City Chiefs. Jack Kemp, a Los Angeles native, was also on the Steelers' roster before being cut. Like Blanda, Parilli, Namath, and Dawson, he became a star in the AFL in the 1960s, as the Steelers went downhill until finally drafting and signing Louisiana native Terry Bradshaw in 1970. By the time Western Pennsylvania had also produced future Hall-of-Famers Joe Montana, Dan Marino and Jim Kelly, Bradshaw and his teammates had long since turned the Steelers from a laughingstock into one of the NFL's most successful and beloved franchises.

The 1970s: The Steel Curtain dynasty

1970–71: Initial Struggles

The Steelers' luck began to take a turn for the better with the hiring of coach Chuck Noll in early 1969, though he too won only a single game in his inaugural season (their worst since 1941), defeating the Detroit Lions in the season opener before losing the next 13 games. Joe Paterno had turned down the job before it was offered to Noll.

The team's luck also continued when they won a coin toss with the Chicago Bears after the 1969 season (both teams went 1–13 in the 1969 season, with the Bears' lone win coming at the Steelers' expense) to gain the rights to draft Louisiana Tech superstar Terry Bradshaw with the first selection in the 1970 NFL Draft. As poor as the 1969 season was, it turned out to be a springboard for one of the most successful decades any NFL team has ever had.

Noll's most remarkable talent was in his draft selections, taking "Mean" Joe Greene in 1969, Terry Bradshaw and Mel Blount in 1970, Jack Ham in 1971, Franco Harris in 1972, and Mike Webster, Lynn Swann, John Stallworth, and Jack Lambert in 1974. According to the NFL Network 1974 is the best draft class in the history of the NFL with Webster, Swann, Stallworth, & Lambert all in the Hall of Fame, and all four won four Super Bowl Championships.[110] This group of players formed the base of one of the greatest teams in NFL history.

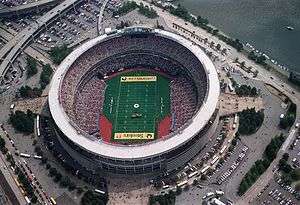

1970 was a turning point year for the Steelers. The team, along with the Cleveland Browns (with whom the intense "Turnpike Rivalry" developed) and the Baltimore Colts, joined the former American Football League (AFL) teams in the new American Football Conference (AFC), following the AFL–NFL merger that year. The team also received a $3 million relocation fee, which was a windfall for them; for years they rarely had enough to build a true contending team.[111] The Steelers moved into Three Rivers Stadium, and Terry Bradshaw, picked first overall in the draft, started at quarterback. Myron Cope, thought by many as a Pittsburgh institution, entered the broadcast booth for a 35-year career as a Steelers radio commentator. The initial results, though an improvement over the late 1960s, were still unimpressive. Pittsburgh lost its season opener against the Oilers and Terry Bradshaw struggled for much of the season, being sacked for a safety in each of his first three games and throwing 24 interceptions on the way to a 5–9 record. The local media subjected him to harsh criticism for a long time. In 1971, Bradshaw threw 22 interceptions during a 6–8 season.

1972–73: The Immaculate Reception

1972, however, was the breakthrough year, and the beginning of an NFL dynasty. Rookie Franco Harris joined the team and ran for 1,055 yards and scored 11 touchdowns. Pittsburgh finished 11–3, first place in the AFC Central, and made the playoffs for the first time since 1947.

Their first playoff game, against the Oakland Raiders, at Three Rivers Stadium, featured one of the best-known plays in league history: the Immaculate Reception. On 4th down from the Pittsburgh 40-yard line with 22 seconds left and trailing 7–6, Bradshaw threw a pass intended for John "Frenchy" Fuqua. Raiders defensive back Jack Tatum knocked it away, but it was scooped up at ankle-height before hitting the turf by Franco Harris, who took it into the end zone for the winning touchdown and a 13–7 victory. In the AFC Championship the following week, the Steelers lost 21-17 to the "perfect" Miami Dolphins, who finished the season 17–0. It was a disappointing finish, but it started a run of eight straight playoff appearances. Arguably the most defining and memorable play in the history of the NFL, the Immaculate Reception thrust the Steelers into its glory years of the '70s.

After an 8–1 start in 1973, a losing streak late in the season cost the Steelers several home games during the playoffs, and they lost a tiebreaker to the Cincinnati Bengals for first place in the division at 10–4. The Steelers traveled to Oakland for the first round of the playoffs and lost 33–14.

1974: First Super Bowl

The Steelers selected the nucleus of the "Steel Curtain" defense in the 1974 draft. This allowed the team to reach the top for the first time. Terry Bradshaw was benched for poor performance early in the season and replaced as starter by Joe Gilliam, but eventually was reinstated after Gilliam did no better. The Steelers finished 10–3–1 and walked away with the division title, with "Mean" Joe Greene winning Defensive Player of the Year honors.

After defeating Buffalo Bills and Oakland Raiders with relative ease in the AFC playoffs, the Steelers met the Minnesota Vikings in New Orleans for Super Bowl IX. The game was a defensive struggle: the only scoring in the first half was a safety scored by the Steelers when Minnesota quarterback Fran Tarkenton was sacked in the end zone. In the second half, the Steelers scored a touchdown after a fumbled kickoff and clinched it with a late Larry Brown touchdown. The Steelers won 16–6, and had finally earned a championship after 42 years of futility.

1975: Second Super Bowl

The team had an even better 1975 season. Pittsburgh ran off an 11-game winning streak and gave up more than twenty points in only two games. Mel Blount was named AFC Defensive Player of the Year, Franco Harris had 1,246 rushing yards (second behind O.J. Simpson), and Lynn Swann caught 11 touchdown passes. Terry Bradshaw delivered a much better performance than in his previous seasons, with 2,055 passing yards, 18 TDs, and only nine interceptions. The Steelers finished 12–2, best in the AFC. In the playoffs, Pittsburgh defeated the Baltimore Colts 28–10 in the first round, and survived a late scare from the Oakland Raiders (and a concussion by Swann) to win 16–10 in the AFC Championship.

The Steelers made their second straight Super Bowl, this one against the Dallas Cowboys in Miami. Down 10–7 in the fourth quarter, Roy Gerela kicked two field goals and Bradshaw threw a 64-yard touchdown pass to Swann to put Pittsburgh in the lead for good. After the Cowboys came back with a touchdown of their own, Roger Staubach threw a last-second interception that sealed a 21–17 win for the Steelers. Lynn Swann had returned from his injuries and racked up four receptions for 161 yards and a TD in the Super Bowl, earning him the title of game MVP.

1976–77: Playoff losses

The two-time defending champions got off to a rough start in 1976, losing four of their first five games. The team regrouped and, based on their powerful defense, won their last nine regular season games, five of which were shutouts. For the third consecutive year, a Steelers player (this time Jack Lambert) won the AFC Defensive Player of the Year award. Pittsburgh finished 10–4 and blew out the Colts 40–14 in the divisional playoffs. In the AFC Championship, an injury-plagued Steeler team lost 24–7 to their perennial playoff nemeses and eventual Super Bowl champions, the Raiders.

Pittsburgh's 1977 campaign was a relative disappointment. Bradshaw threw more interceptions than touchdowns, fullback Rocky Bleier had only half as productive a season as he did in 1976, and the famed Steel Curtain defense gave up nearly twice as many points. The team still won the division at 9–5, but lost 34–21 to the Denver Broncos in the divisional playoff.

1978: Third Super Bowl

The Steelers kicked off 1978 with controversy, when during a post-draft mini camp they were caught wearing shoulder pads in violation of league rules. They would lose a draft pick the following year for the infraction. Pittsburgh posted a 14–2 regular season record, best in the NFL. In the playoffs, the Steelers blew away the Denver Broncos and Houston Oilers by a combined score of 67–15 en route to Super Bowl XIII.

That game, a rematch with the Cowboys, is considered by many to be one of the greatest Super Bowls of all time. Bradshaw threw four touchdowns, but the Cowboys never were out of it, thanks in part to a fumble recovery for a touchdown by Mike Hegman. After Swann and Harris scored touchdowns 19 seconds apart in the fourth quarter, the Cowboys countered with scores of their own by Billy Joe Dupree and Butch Johnson to pull within four points with 22 seconds left. The Steelers recovered the onside kick and pulled off a 35–31 win. Terry Bradshaw was named game MVP.

1979: Fourth Super Bowl

The 1979 season was the last season of the dynasty. Bradshaw threw for over 3,700 yards and 26 touchdowns and John Stallworth had 1183 yards receiving. The Steelers finished 12–4, once again tops in the AFC Central. In the playoffs they defeated the Dolphins 34–14 and the Oilers 27–13, to meet the Los Angeles Rams in their fourth Super Bowl.

The Rams had a number of ex-Steelers staff members, and thus knew all of their opponent's plays, audibles. and hand signs. With this knowledge, they played the Steelers hard for three quarters. Bradshaw threw three interceptions, but also had two long touchdown passes in the second half (one to Swann and one to Stallworth). The Rams couldn't recover and Pittsburgh won 31–19.

The team's success in this era led to the expansion of its fanbase beyond its geographic region. Today, Pittsburgh remains among the league leaders in merchandise sales, and draws fans from across the country to its games. This loyal fan following is sometimes called Steeler Nation (predating the similarly popular '70s powerhouse, the Oakland Raiders Raider Nation) [Birth of a Nation: Capturing The Identity of a Region. byline, John Mehno], the term was coined by NFL Films as the producers studied the phenomenon of fans swarming Three Rivers from all directions and pronounced them the 'Steeler Nation'. They are known for employing the terrible towel (a bright yellow cloth) as its unofficial symbol (created by Myron Cope), and as a rallying sign during Steelers' games.

1980–1991: Decade of decline

The Steelers were hit with the retirements of all their key players from the Super Bowl years, with Rocky Bleier after the 1980 season, "Mean Joe" Greene and L. C. Greenwood after the 1981 season, Lynn Swann and Jack Ham after 1982, Terry Bradshaw and Mel Blount after 1983, Jack Lambert and Franco Harris after 1984 and John Stallworth after 1987.

1980–1981: Missing the playoffs

"One for the thumb in '81" was the rallying cry of the Steelers during the 1980 season as they began their quest for a fifth Super Bowl Ring.[112] It was not so. Hard luck, age, injuries, and an off year by Terry Bradshaw left the Steelers with a 9–7 record, missing the playoffs. This marked the end of the dynasty. They finished the 1981 season with an 8–8 record.

1982–83: Losses to Chargers and Raiders

Major changes were made to the Steelers during the next season, including coach Chuck Noll's installment of a 3–4 defense to deal with the league's new pass-oriented rules changes and the departure of Joe Greene and L. C. Greenwood. Pittsburgh managed a 6–3 record nonetheless in 1982 (which was shortened due to a players' strike) and made it to the playoffs for the first time since 1979. In the playoffs they lost when Kellen Winslow caught two touchdowns in the 4th quarter of their first playoff game, a 31–28 loss to the San Diego Chargers.

Bradshaw was sidelined with an elbow injury for most of the 1983 season (his last), with Cliff Stoudt picking up the reins behind center. Franco Harris ran for 1,007 yards in his last season in Pittsburgh (he wound up with the Seattle Seahawks for his final year), and Keith Willis recorded a career-best 13 sacks. The streaky Steelers lost four of their last five regular season games, but their 10–6 record was still good for a division title. The Steelers closed the regular season with an emotional victory against the New York Jets in the last football game ever played at Shea Stadium. Bradshaw, returning from injury, led the Steelers to the lead with two touchdown passes. He left the game in the first half after hearing a "pop" in his elbow when making his final pass, a touchdown. The Steelers made another quick first-round playoff exit, a 38–10 embarrassment against the Los Angeles Raiders.

1984: Loss to Marino's Dolphins

1984 was supposed to be a rebuilding year. Mark Malone and David Woodley split quarterbacking duties, with Frank Pollard taking over at running back and Offensive Rookie of the Year Louis Lipps shining at wide receiver. The Steelers' 9–7 record won them another division title. Among the nine victories, the Steelers handed San Francisco its only loss of the season, en route to an impressive 18 win season and Super Bowl championship. In the divisional playoff against the Denver Broncos, the Steelers came back in the fourth quarter to win 24–17, but they lost the AFC Championship to Dan Marino (the Pittsburgh native whom the Steelers passed up in the 1983 Draft) and the Dolphins, 45–28.

1985–1987: Brief Collapse

Despite career seasons from Lipps and Pollard, the Steelers' 1985 campaign collapsed in December, with them losing four of their last five to finish at 7–9. In 1986, Malone took over the QB job by himself and Earnest Jackson (who came off back-to-back 1000-yard seasons with the Philadelphia Eagles) was added to the offensive backfield, but the team fared no better, at 6–10. An 8–7 record in 1987 was not enough to save Malone's job in Pittsburgh. Bubby Brister became the Steelers' new starting quarterback.

1988–89: 5–11, Loss to Elway

The 1988 season was the worst for the Steelers in twenty years, with a 5–11 record. Mike Webster was cut during the offseason. The 1989 team also got rough start, but won five of their last six to finish 9–7, enough for a wild card playoff spot. In the wild-card playoff game against the Houston Oilers, the Steelers staged a desperate fourth-quarter comeback to win 26–23 in overtime on a 50-yard field goal by Gary Anderson. The game cost Houston coach Jerry Glanville his job. However, in their divisional game against the Denver Broncos, it was John Elway who staged the last-minute comeback and the Steelers went home with a 24–23 loss. Defensive back Rod Woodson, in his third season, made the first of seven consecutive Pro Bowls.

1990–91: 9–7, 7–9

The Steelers finished 9–7 in 1990 led by the No. 1 defense in the NFL in terms of yards allowed. The defense was led by the secondary (mainly the superb Rod Woodson) which was particularly effective limiting opposing passers to just 9 touchdown passes while intercepting 19 (the Steelers intercepted 24 total as a team). The 1990 season ended with another disappointment however as the Steelers lost twice in three weeks to the Cincinnati Bengals, and lost the season's final game on the road to the Houston Oilers to miss out on the playoffs.

The 1991 season saw rookie quarterback Neil O'Donnell show some flashes of brilliance, but the rest of the team faltered and the Steelers finished 7–9.

1992–2006: Cowher's Years

Chuck Noll, the Steelers' coach since 1969, retired at the end of the 1991 season. Noll was replaced by Kansas City Chiefs defensive coordinator Bill Cowher, a native of the Pittsburgh suburb of Crafton. Cowher led the Steelers to the playoffs in each of his first six seasons as coach, a feat that had only previously been accomplished by legendary coach Paul Brown of the Cleveland Browns.

1992: Upset by Buffalo

Cowher made an immediate impact in the 1992 season, as did third-year running back Barry Foster whose 1,690 yards was second in the NFL behind Emmitt Smith. Woodson recorded six sacks, a career high. The Steelers' 11–5 record won them the AFC Central title and a first-round playoff bye. Their hopes, however, came to a crashing end against the surging Buffalo Bills, in a 24–3 loss.

1993: Upset by Chiefs

The Steelers collapsed near the end of the 1993 season, starting 6–3 but finishing 9–7. They clinched the final playoff spot at 9–7, and travelled to Arrowhead Stadium to face the Kansas City Chiefs in the wild card round. Leading 24–17 with two minutes left, the Steelers defense gave up a Joe Montana fourth-down touchdown pass to little-known Tim Barnett to tie the game. In overtime, the Chiefs won on a Nick Lowery field goal.

1994: Upset by Chargers

The 1994 season brought back memories of the 1970s Steeler teams. Barry Foster was joined in the backfield by rookie Bam Morris, and together they gained almost 1,700 rushing yards. The "Steel Curtain" defense made a resurgence, with Kevin Greene responsible for 14 sacks and Greg Lloyd tacking on 10 more. The Steelers' 12–4 record clinched them home-field advantage throughout the AFC playoffs. In the divisional playoff Pittsburgh walloped the Cleveland Browns 29–9, and were heavily favored in the conference championship against the San Diego Chargers. The Steelers seemed to dominate when the numbers were crunched: O'Donnell passed for 349 yards to Stan Humphries' 165, and had a nearly 2–1 edge in time of possession. But they gave up a 13–3 lead in the 3rd quarter when Alfred Pupunu and Tony Martin caught touchdowns of 43 yards each, and it was the Chargers who advanced to Super Bowl XXIX, by the score of 17–13. The 1994 Steelers finished their disappointing season three yards away from their first Super Bowl appearance since 1980 as an O'Donnell pass to Foster was batted down. This play epitomized the Steelers' season – incomplete. AFC Championship collapses, unfortunately for the Steelers, would become a hallmark of the Cowher era.

1995: Loss in the Super Bowl

The Steelers' 1995 campaign was no less dominant. Foster left the team, but Erric Pegram (picked up from the Atlanta Falcons) made up for it with an 800-yard season. Yancey Thigpen amassed 1,307 receiving yards and Willie Williams had seven interceptions. The Steelers' 11–5 record once again won them the division and a first-round bye. As in 1994, the Steelers dominated in the divisional playoff (a 40–21 win over the Buffalo Bills), but the cinderella Indianapolis Colts put up a fight in the AFC championship. There were four lead changes, the last when Bam Morris scored a one-yard touchdown with 1:34 remaining. Colts quarterback Jim Harbaugh threw a "hail mary" that was dropped by Aaron Bailey in the end zone. The Steelers narrowly won, 20–16, and went on to play the Dallas Cowboys in Super Bowl XXX.

The Cowboys, a team that thought themselves to be just as dominant in the 1990s as the Steelers were in the 1970s heyday, jumped to a quick 13–0 lead. Pittsburgh showed some signs of life, such as a Yancey Thigpen touchdown before halftime, and a surprise onside kick recovery that led to a Bam Morris touchdown run narrowing the score to 20–17, late in the 4th quarter. The Steeler defense quickly forced Dallas into punting the ball back to the Steeler offense and Neil O'Donnell threw his second and worst interception of the game, similar to his first, halting the Steelers come from behind win. Both interceptions gave Dallas easy touchdown situations. O'Donnell's three interceptions contributed heavily to the Steelers' 27–17 loss.

1996: Wild Card Year

Super Bowl XXX was O'Donnell's last game as a Steeler, as he signed with the New York Jets as a free agent in the offseason. Pittsburgh had drafted Kordell Stewart in 1995, but he remained a backup through the 1996 season. Mike Tomczak received the starting duties. The Steelers also traded for running back Jerome Bettis from the St. Louis Rams, who ran for 1,400 yards in his first year in the Steel City. A late-season decline was hurting the Steelers Super Bowl chances, but their 10–6 record still won them the division. Pittsburgh won their wild-card playoff game handily (42–14 over the Colts), but lost just as handily, 28–3, to the New England Patriots in the divisional playoff.

1997: Comeback Contained

Stewart was given the starting quarterback job in 1997 after Tomczak failed to impress. Stewart did impress fans, however, in his first full season: 3,000 passing yards and 21 touchdowns. Bettis had another 1,000-yard rushing season, and Thigpen had 1,000 yards receiving to boot. The Steelers once again won the AFC Central, but their 11–5 record also gave them a first-round playoff bye. They narrowly won a 7–6 defensive struggle against the Patriots in the divisional playoff, setting the stage for an AFC Championship showdown at Three Rivers Stadium against the Denver Broncos. Kordell Stewart scored early, going for 33 yards with one of his well-known scrambles, but the Broncos exploded in the second quarter (aided by two questionable interference calls). A late Steelers comeback was squashed and the eventual Super Bowl champion Broncos went on to win 24–21.

1998: "Hea-tails"

It looked like the Steelers would be back in the playoffs for most of the 1998 regular season, going 7–4 in their first eleven games. But two losses to the Cincinnati Bengals and a loss on Thanksgiving to the Detroit Lions kept the Steelers out of the playoffs. The Thanksgiving game against the Detroit Lions in 1998 is most known for the infamous coin flip call before overtime. The game was tied 16–16 at the end of regulation when the referee told team captain Jerome Bettis to call "heads" or "tails" as he flipped the coin in the air. Bettis stammered while making the call, and referee (Phil Luckett) stated "the Steelers called heads; it's tails." This caused an uproar from Bettis and the Steelers, as replays seemed to show that Bettis clearly called "tails." Contrary to many press reports, Luckett did not make a mistake in this incident. A week after the game, the tape was enhanced by local Pittsburgh TV station KDKA-TV and Bettis is clearly heard saying "hea-tails." A sideline microphone enhancement also clearly had Bettis telling Coach Bill Cowher that (Bettis) had said "hea-tails." The Steelers never got to touch the ball again and went on to lose 19–16. They would lose their next four games and would end up finishing 7–9.

1999: 6–10

The Steelers fell into turmoil in 1999. Stewart was benched partway through the season and Tomczak was given back his starting job. Pittsburgh's mostly new receiving corps (including future star Hines Ward) showed their inexperience at times, and the team finished 6–10, their worst showing in eleven years.

It has become an article of faith among NFL pundits that the Steelers do not have a bad team two years in a row—they have never lost 10 or more in consecutive years since the 1970 AFL-NFL Merger.

2000: 9–7, playoffs missed

In the 2000 season, the last one at Three Rivers Stadium, Kent Graham was given a chance to start at quarterback. His below average play and nagging injuries early in the season gave Kordell Stewart another chance to reclaim the starting quarterback role. The Steelers started to improve by teamwork alone. Jerome Bettis had a 1,341-yard season. Rookie wide receiver Plaxico Burress joined the team to complement Hines Ward. Linebacker Jason Gildon, the team's only Pro Bowler, had a career-best 13.5 sacks. Up and coming linebacker Joey Porter posted 10.5 sacks as the team finished back above .500 with a 9–7 record. The defense did not allow a touchdown in 20 consecutive quarters during one stretch, just two shy of the NFL record set by the 1976 Steelers, also known as the Steel Curtain. After a hard fought season, exacerbated by a 0–3 start, the Steelers failed to make the playoffs for the third consecutive season under Bill Cowher. The Steelers did win their final game at Three Rivers Stadium by defeating the Washington Redskins 24–3, ending the season with a 9–7 record. In an unusual move, the NFL formally apologized to the team three times for missed or blown calls in games against Cleveland, Tennessee, and Philadelphia that may have contributed to the team's losses.

2001: Loss to New England

The Steelers opened Heinz Field in the 2001 season. Both Ward and Burress had 1,000-yard receiving seasons, and linebacker Kendrell Bell was named NFL Defensive Rookie of the Year. Bettis had to sit out the last five games of the regular season and start of the playoffs with a knee injury, but Chris Fuamatu-Ma'afala and Amos Zereoue ably filled in. The Steelers' 13–3 record got them home field advantage throughout the playoffs.

Zereoue, filling in for Bettis, scored two touchdowns in the divisional playoff against the defending Super Bowl champion Baltimore Ravens, which the Steelers won 27–10. Pittsburgh then hosted its fourth AFC championship game in eight years, this one against the New England Patriots. Optimism was high as Bettis made his return. The Patriots jumped out to a big lead thanks to two special teams touchdowns, but the Steelers tried a third-quarter comeback with rushing touchdowns by Bettis and Zereoue. Kordell Stewart's final two drives both ended in interceptions, however, and the eventual Super Bowl champion Patriots won the game 24–17.

2002: Narrow Loss to Titans

Stewart's inability to win big games and tendency to throw interceptions cost him the starting job once again early in the 2002 season. Journeyman Tommy Maddox, who won the XFL MVP after the league's only season, became the starting quarterback. Maddox lost only three games as the Steelers finished 10–5–1, tops in the new AFC North division. (Stewart, who made a short comeback after Maddox was injured later in the year, was cut and later resurfaced with the Chicago Bears.)

They faced their longtime rivals, the Cleveland Browns, in the wild card playoff game. The Steelers were down 24–7 in the third quarter, but Maddox led them on a wild comeback. Jerame Tuman, Hines Ward, and Chris Fuamatu-Ma'afala all scored fourth-quarter touchdowns to win the game 36–33. The divisional playoff against the Tennessee Titans was just as dramatic. Hines Ward tied the game early in the fourth quarter with a 21-yard touchdown, and the game eventually went to overtime. Tennessee won the toss and Titans kicker Joe Nedney lined up for a field goal, which he made. But the Steelers called timeout so the field goal did not count. Nedney's second try went wide right, but the Steelers were called for running into the kicker on Dewayne Washington. The third try was good and officially counted as the game winner, but over protests by Bill Cowher who thought he called another timeout first. The 34–31 loss was another disappointing end to the season for the Steelers.

2003: 6–10

2003 was an overall disappointment. Due to injuries on the offensive line, and Maddox's previous success in the passing game, the Steelers strayed from their typical run-heavy offense. However, Maddox threw only 18 touchdowns to 17 interceptions, causing fans to wonder if the previous season was a fluke. Jerome Bettis and Plaxico Burress both failed to reach 1,000 yards. The Steelers collapsed to 6–10.

2004 season: 15–1

In the 2004 draft, the Steelers took quarterback Ben Roethlisberger from Miami University (Ohio) in the first round. Maddox kept the starting job until he was injured in the second game of the season, in Baltimore, against the Ravens. Roethlisberger was pushed into action and immediately wowed fans. "Big Ben" did not lose a game during the entire regular season, setting a record for most consecutive games won with a rookie quarterback to start a career. Included were back-to-back convincing wins over the New England Patriots (breaking their record 21-game winning streak) and eventual NFC champion Philadelphia Eagles. By the end of the season, Roethlisberger and the rest of the Steelers were starting to show signs of wear, but they still escaped with victories every time. The Steelers completed the 2004 regular season with the best record in the NFL at 15–1, which is also their best 16-game season.

After 2003's failed attempt to focus on the passing game, the 2004 team returned to the typical Steelers formula, a run-heavy offense (61/39 run-pass ratio) and a strong defense. The team's dominant running game, featuring Jerome Bettis and Duce Staley (acquired prior to the season in free agency), was bolstered by an efficient and often explosive passing attack led by Roethlisberger and receivers Burress, Ward, and Antwaan Randle El. The defense, one of the league's best, was anchored by Pro Bowl linebackers James Farrior and Joey Porter and Pro Bowl safety Troy Polamalu. Only three previous teams (The '84 49ers, the '85 Bears, & the '98 Vikings) have had a 15-win season, with the Steelers being the first AFC team to accomplish this feat. As a result of this dominant season, the Steelers received home field advantage throughout the AFC playoffs.

Their divisional playoff game was against the Wild Card New York Jets. Roethlisberger threw two interceptions, one of which was returned for a touchdown by Reggie Tongue, but a Hines Ward touchdown catch tied the game at 17–17 in the fourth quarter. Jets kicker Doug Brien had two chances to win the game with a field goal in the final two minutes of regulation, but one kick hit the crossbar, while the other went wide left. Jeff Reed kicked a field goal 11:04 into the extra period to win the game, 20–17.

The Steelers were back in the AFC Championship, once again in Pittsburgh, for a rematch with the Patriots. New England went out to a big lead early after two first-quarter turnovers by the Steelers. In the second quarter, Rodney Harrison intercepted Roethlisberger (who had three picks overall) and returned it for a touchdown. The Steelers showed some signs of life in the third quarter, but it was not enough. The Patriots, another dynasty team that has been compared with the 1970s Steelers, won 41–27. This defeat marked the fourth time in ten years that the Steelers had lost the conference title game at home under Bill Cowher.

2005 season: Fifth Super Bowl

Despite losing Plaxico Burress to free agency (he ended up with the New York Giants), the Steelers took some steps to ensure a return to the postseason. They first selected TE Heath Miller from the University of Virginia in the 2005 NFL Draft. Other picks included Florida State CB Bryant McFadden, Northwestern University OG Trai Essex, Georgia University WR Fred Gibson, and Temple University LB Rian Wallance.

In 2005, the Steelers hoped to make another post-season run. Injuries to Jerome Bettis and Duce Staley caused Willie Parker to become the Steelers' starter at running back, and he acquitted himself very well in two convincing wins against the Tennessee Titans (34–7) and Houston Texans (27–7) to open the season. In the next game, however, the visiting New England Patriots handed Ben Roethlisberger his first regular-season loss as the Steelers lost the much-hyped rematch of the 2004 AFC Championship Game 23–20. Two weeks later, Pittsburgh came back to defeat the throwback-clad San Diego Chargers 24–22 on a 40-yard field goal by Jeff Reed. The victory proved costly as Roethlisberger suffered an injury when he was hit on his left knee by the helmet of Chargers rookie lineman Luis Castillo. So Tommy Maddox was named starter for their home game against the Jacksonville Jaguars. The Steelers struggled throughout the game, as Maddox threw two interceptions through regulation, but they managed to tie at 17 going into OT. Maddox threw an interception to Jags DB Rashean Mathis, who returned it 41 yards for a touchdown, as the Steelers fell, 23–17. Maddox's off-field arguments with head coach Bill Cowher cost him his No. 1 back-up spot. Roethlisberger was able to play in their next road game against their division rival, the Cincinnati Bengals. Despite winning 27–13, his left knee needed surgery. Roethlisberger fought through a lot of pain in the Steelers' 20–19 Monday Night victory over the Baltimore Ravens but reaggravated his knee injuries. Charlie Batch was named the starter, and he provided victories over the struggling Green Bay Packers (20–10 on the road), and against their rust belt rival, the Cleveland Browns (34–21 at home), where during the game, wide receiver Hines Ward set the Steelers record for most career receptions (543), breaking John Stallworth's mark of 537. Batch broke his hand, which sent him to the sidelines. Tommy Maddox was given the start for their road game against the Ravens, but again, he showed his inefficiency, as the Steelers fell in overtime 16–13. After Roethlisberger's return, the Steelers lost their first two games against the then-undefeated Indianapolis Colts (26–7 on the road) and at home against the resurgent Bengals (38–31), but recovered to win the last four regular-season games (21–9 vs. Bears, 18–3 @ Vikings, 41–0 @ Browns, and 35–21 vs. Lions) to clinch the sixth and last seed in the AFC playoffs.

During the last game of the regular season in Pittsburgh, the Steelers fans gave Jerome Bettis a standing ovation when he was taken out of the game in the fourth quarter by Bill Cowher. It was the last game in Pittsburgh for Bettis, as he announced his retirement after the Steelers' ultimate victory in Super Bowl XL. Bettis finished the game with 41 yards rushing and 3 touchdowns, and gave the team a boost after the Lions had taken a 14–7 first quarter lead.

| Wikinews has related news: Steelers defeat Lions to advance to NFL playoffs |

On Sunday, January 8, 2006, the Steelers traveled to Paul Brown Stadium for their Wild Card match-up against the Cincinnati Bengals. On the Bengals' second offensive play, Bengal quarterback Carson Palmer launched a 66-yard completion – the longest in Bengals' playoff history – to receiver Chris Henry while Steelers defensive tackle Kimo von Oelhoffen tried to sack him. Many Bengals fans believed von Oelhoffen's hit to Palmer's leg, striking his left knee from the side and was carted off the field, was intentional. A magnetic resonance imaging test revealed that both Palmer's anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligaments were torn by von Oelhoffen's contact, which also caused cartilage and meniscus damage. Von Oelhoffen's hit did not generate a defensive penalty because Bengals guard Eric Steinbach pushed von Oelhoffen into Palmer.

Backup quarterback Jon Kitna filled in for Palmer and threw 1 touchdown pass and two interceptions. Despite trailing after the first quarter, the Steelers came within three points, trailing 17–14 at the half. Eventually, they shut out the Bengals in the second half and scored 17 points to win, 31–17.

On Sunday, January 15, the Steelers traveled to the RCA Dome in Indianapolis, Indiana where they faced the No. 1 seeded Colts, and defeated them 21–18 in spite of a highly improbable fourth quarter—including a controversial call reversal that turned a crucial Troy Polamalu interception into an incomplete pass—which found the suddenly revitalized Colts offense with a chance to turn the game around. After recovering an unlikely Jerome Bettis fumble on the Colts 1 with just over a minute remaining, Colts cornerback Nick Harper sped downfield toward what would have been a game-winning touchdown, only to be tripped up by Steelers quarterback Ben Roethlisberger in a shoe-string tackle. This heads-up play probably prevented a game-winning touchdown for the Colts. The Steelers defense held their ground on the ensuing Colts drive, leaving the Colts with just one last chance to tie and send the game into overtime. But Colts kicker Mike Vanderjagt, one of the most accurate kickers in NFL history, missed a 46-yard field goal attempt—wide right—with :18 left in the fourth quarter. The game was the first time in NFL history that a sixth seed (Pittsburgh) defeated a first seed (Indianapolis Colts) in the playoffs. It also marked the first time that a sixth seed would get to play in a Conference Championship game.

On Sunday January 22, 2006, the Steelers won their 6th AFC Championship at INVESCO Field at Mile High in Denver, Colorado when they beat the Denver Broncos 34–17. Quarterback Ben Roethlisberger completed a 21 out of 29 passes, 2 of which were touchdowns. He also ran for another touchdown as he led the team to victory. It marked the 1st time since the 1985–'86 New England Patriots and the second time in NFL history that a Wild Card team would get to the Super Bowl after winning the Wild Card Round, the Divisional Round, and the Conference Championship on the road. It also marked the first time that a sixth-seeded team would get to play in the Super Bowl.

In the Steelers' first trip to the Super Bowl since the 1995 season, they defeated the Seattle Seahawks 21–10 in Super Bowl XL on February 5, 2006, at Ford Field in Detroit, Michigan. The game had been hyped as a homecoming for Detroit native Jerome Bettis. Records were set for longest run from scrimmage (75 yards for touchdown by Willie Parker of the Steelers), longest interception return (76 yards by Seahawks CB Kelly Herndon), and the first touchdown pass by a wide receiver (thrown by Antwaan Randle El to Hines Ward on a reverse).

The Steelers become the first 6th-seeded team, since the NFL changed to a 12-team playoff format in 1990, to go to the Super Bowl and win. Their playoff campaign included defeating the first (Indianapolis), second (Denver), and third (Cincinnati) seeded AFC teams en route to the Super Bowl victory against the first seeded Seahawks from the NFC. Also, they are the first NFL team to win 9 road games. Roethlisberger became the youngest QB to win a Super Bowl. They successfully tied with the San Francisco 49ers and the Dallas Cowboys for the most Super Bowl titles with five.

2006: 8–8, missed playoffs

The 2006 Pittsburgh Steelers season began with the team trying to improve on their 11–5 record from 2005 and trying to defend their Super Bowl XL championship. They finished the season 8–8 and did not make it to the playoffs.

Hoping to end their season on a high note, the Steelers flew to Paul Brown Stadium for an AFC North rematch with the Cincinnati Bengals. After a scoreless first quarter, Pittsburgh drew first blood in the second quarter with RB Willie Parker getting a 1-yard TD run. Afterwards, the Bengals would manage to salvage a 34-yard field goal by kicker Shayne Graham. After a scoreless third quarter, Cincinnati took the lead by getting a Willie Parker fumble and ending it with QB Carson Palmer completing a 66-yard TD pass to WR Chris Henry. Parker managed to make amends with another 1-yard TD run. However, the Bengals went back into the lead with Palmer completing a 5-yard TD pass to TE Tony Stewart. The Steelers would manage to tie the game late in the game with kicker Jeff Reed nailing a 35-yard field goal. Cincinnati quickly managed to get into field goal range, but Graham's 39-yard field goal went wide right. In overtime, Pittsburgh took advantage and won with QB Ben Roethlisberger's 67-yard TD pass to rookie WR Santonio Holmes. With the win, not only did the Steelers end their season at 8–8, but they also wiped out any hope that the Bengals had of reaching the playoffs.

2007–present: Mike Tomlin's reign

2007: 10–6, Division Winners

The 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers season saw the team improve upon their 8–8 record from 2006, finish with a record of 10–6, and win the AFC North Division. The season marked the 75th anniversary of the Steelers franchise.The Steelers' 2007 schedule included two notable playoff rematches. The Steelers played the New England Patriots December 9 for the first time in the regular season since 2005, when they lost at home on a last-second Adam Vinatieri field goal 23–20. The 34–13 loss was also the Steelers' first visit to Foxboro, Massachusetts since 2002. The Steelers defeated the Seattle Seahawks 21–0 in week 5 on October 7, the teams' first meeting since the Steelers' 21–10 victory in Super Bowl XL 20 months earlier. The week 5 match was the Steelers' and Seahawks' first meeting in Pittsburgh since 1999 as well as the Seahawks' first-ever visit to Heinz Field. Another notable game occurred December 20 when the Steelers defeated the St. Louis Rams, 41–24, for their first-ever road win over the Cleveland/Los Angeles/St. Louis Rams (1–9–1). It was the two teams' first-ever meeting in St. Louis, a city the Steelers last visited in 1979 (a 24–21 win over the then-St. Louis Cardinals at Busch Memorial Stadium).

Six players from the Steelers were selected to play in the 2007 Pro Bowl. Two started, two were selected to the reserve squad, and two did not play due to injury.

- 7 Ben Roethlisberger – Quarterback (reserve)

- 39 Willie Parker – Running back (injured, did not play)

- 43 Troy Polamalu – Strong safety (injured, did not play)

- 66 Alan Faneca – Offensive guard

- 92 James Harrison – Outside linebacker

- 98 Casey Hampton – Defensive tackle (reserve)

2008: Sixth Super Bowl

Entering the 2008 season, the Pittsburgh Steelers lost Alan Faneca, after his contract expired and he signed with the New York Jets. The Steelers also signed quarterback Ben Roethlisberger to an eight-year, $102 million contract, the largest in franchise history. The Steelers also drafted Rashard Mendenhall, running back from Illinois, with the 23rd overall pick in the 2008 NFL Draft as well as top wide receiver prospect Limas Sweed of Texas with the 53rd overall pick. With injury to Willie Parker and uncertainty about his future production, Mendenhall was drafted to be the next Steelers running back of the future. The regular season went well with the team winning twelve games and losing four, all to strong opponents, with their only losses going to the Philadelphia Eagles, the New York Giants, the Indianapolis Colts, and the Tennessee Titans (who had the best record in the league). The team thus earned a first-round bye and home advantage through the playoffs. James Harrison was voted as the 2008 AP Defensive Player of the Year with a monstrous regular season performance with 16 sacks (fourth in league) and 7 forced fumbles (first in the league). Troy Polamalu also had a great season, gaining seven interceptions which was tied for second in the league, trailing only Ed Reed of the Baltimore Ravens who had 9. Beating San Diego in the divisional round, they faced their AFC North rival Baltimore in the conference championship and soundly defeated them. Thus, the Steelers made it to their seventh Super Bowl. Their opponent was the Arizona Cardinals, a team that had not appeared in any league championship since 1948.

Super Bowl XLIII was played on February 1, 2009 at the Buccaneers' Raymond James Stadium. By halftime, the Steelers were ahead at 17–7. Arizona's effort was hampered by penalties, in particular three personal fouls, but they managed to get ahead after WR Larry Fitzgerald scored a 63-yard touchdown, bringing the score to 23–20. But Pittsburgh's Santonio Holmes was able to convert a 6-yard TD in the final two minutes. With that, the game ended 27–23 and the Steelers gained their sixth championship, becoming the first team to win six Super Bowls since the start of the Super Bowl era.

2009: 9–7, playoffs missed

The defending champions began the 2009 campaign in good form, winning six of their first eight matches. However, a major loss came as the Steelers lost Troy Polamalu in Week 1 against the Tennessee Titans. Troy came back in Week 6 against the Browns and played until Week 10 against the Bengals when he reinjured himself in the game. This effectively ended the rest of Troy's season. But starting in Week 10, things crumbled as Pittsburgh dropped five in a row, including losses to Kansas City and Oakland, two of the league's weakest teams. The ultimate disaster came in Week 14, when an unprepared, injury-compromised Steelers team lost to the 1–11 Cleveland Browns for the first time since 2003. Pittsburgh managed to snap its losing streak in the next game, where they beat Green Bay by one point with Ben Roethlisberger throwing a career-best 504 passing yards. They then won against Baltimore the following week, and on the season ender defeated Miami to finish 9–7. However, the Ravens' victory over Oakland later that day kept Pittsburgh from the playoffs. Throughout the season, the Steelers struggled harshly on special teams, giving up four kickoff return touchdowns. The Steelers sent 4 players to the Pro Bowl: Tight end Heath Miller (76 receptions, 789 receiving yards, and 6 touchdowns), nose tackle Casey Hampton (43 tackles/23 solo, and 2 sacks), and linebackers James Harrison (79 tackles/60 solo, 10 sacks, and 5 forced fumbles) and LaMarr Woodley (62 tackles/50 solo, 13 sacks, and 1 forced fumble).

2010: Upset by Packers