First Hungarian Republic

The First Hungarian Republic[4] (Hungarian: Első magyar köztársaság) or by its contemporary name Hungarian People's Republic (Hungarian: Magyar Népköztársaság) was a short-lived people's republic that existed, apart from a 133-day interruption, from late 1918 until mid-1919. It was established in the wake of the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire following World War I. The Hungarian People's Republic replaced the Kingdom of Hungary and was in turn replaced by another short-lived state.

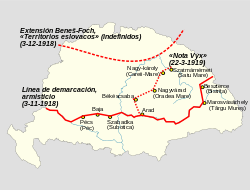

During this period, Hungary was forced to cede lands for the formation of nations based on majority-ethnic groups, who formed Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia, made up of Serbians, Croatians and Slovenes.

Name

"Hungarian People's Republic" was adopted as the official name of the country on 16 November 1918[1][5] and remained in use until the overthrow of the Dénes Berinkey government on 21 March 1919. Following the collapse of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, the Gyula Peidl government restored the pre-communist name of the state on 2 August 1919.[6][7] The government of István Friedrich changed the name to "Hungarian Republic" on 8 August;[8][9][10][11][12] however, the denomination "Hungarian People's Republic"[13][14] appeared on some government-issued decrees during this period.

History

Károlyi era (1918–1919)

The Hungarian People's Republic was created by the Aster Revolution, which started in Budapest on 31 October 1918. That day, King Charles IV appointed the revolt's leader, Mihály Károlyi, as Hungarian prime minister. Almost his first act was to formally terminate the personal union between Austria and Hungary.

On 13 November, Charles issued a proclamation withdrawing from Hungarian politics. A few days later the provisional government proclaimed Hungary a people's republic,[1] with Károlyi as both prime minister and interim president. This event ended 400 years of rule by the House of Habsburg.

The Károlyi government's measures failed to stem popular discontent, especially when the Entente powers began distributing slices of what many considered Hungary's traditional territory to the majority ethnic groups in Romania, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (colloquially Yugoslavia until the name became formal in 1929), and Czechoslovakia. The new government and its supporters had pinned their hopes for maintaining Hungary's territorial integrity on the abandonment of Austria and Germany, the securing of a separate peace, and exploiting Károlyi's close connections in France.

The Entente considered Hungary a partner in the defeated Dual Monarchy, and dashed the Hungarians' hopes with the delivery of successive diplomatic notes. Each demanded the surrender of more land to other ethnic groups. On 20 March 1919, the French head of the Entente mission in Budapest gave Károlyi a note delineating the final postwar boundaries, which the Hungarians found unacceptable.[15] Károlyi and Prime Minister Dénes Berinkey were now in an impossible position. They knew accepting the French note would endanger the country's territorial integrity, but were in no position to reject it. In protest, Berinkey resigned.

Károlyi turned power over to a coalition of Social Democrats and Communists; the latter promised that Soviet Russia would help Hungary to restore its original borders. Although the Social Democrats held a majority in the coalition, the Communists led by Béla Kun immediately seized control and announced the establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic on 21 March 1919.

Re-establishment and dissolution (1919)

After the fall of the Soviet Republic on 1 August 1919, a social democratic government (the so-called "trade union government") came to power under the leadership of Gyula Peidl.[16] A decree was issued on 2 August restoring the form of government and the official state name back to "People's Republic".[6] During its brief existence, the Peidl government began to abrogate the edicts passed by the communist regime.[17]

On 6 August István Friedrich, leader of the White House Comrades Association (a right-wing, counter-revolutionary group), seized power in a bloodless coup with the backing of the Royal Romanian Army.[7] The next day, Joseph August declared himself regent of Hungary (he held the position until 23 August, when he was forced to resign)[18] and appointed Friedrich as Prime Minister. The state was formally dissolved by the new government on 8 August 1919.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 "1918. évi néphatározat" (in Hungarian). hu.wikisource.org. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ Pölöskei, Ferenc; Gergely, Jenő; Izsák, Lajos (1995). Magyarország története 1918–1990 (in Hungarian). Budapest: Korona Kiadó. p. 17. ISBN 963-8153-55-5.

- ↑ Kollega Tarsoly, István, ed. (1995). "Magyarország". Révai nagy lexikona (in Hungarian). Volume 20. Budapest: Hasonmás Kiadó. pp. 595–597. ISBN 963-8318-70-8.

- ↑ "The First Hungarian Republic". The Orange Files.

- ↑ "Minisztertanácsi jegyzőkönyvek: 1918. november 16." (in Hungarian). DigitArchiv. p. 4. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- 1 2 "A Magyar Népköztársaság Kormányának 1. számu rendelete Magyarország államformája tárgyában" (in Hungarian). hu.wikisource.org. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- 1 2 Pölöskei, Ferenc; Gergely, Jenő; Izsák, Lajos (1995). Magyarország története 1918–1990 (in Hungarian). Budapest: Korona Kiadó. pp. 32–33. ISBN 963-8153-55-5.

- ↑ "Minisztertanácsi jegyzőkönyvek: 1919. augusztus 8." (in Hungarian). DigitArchiv. p. 10. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ "Minisztertanácsi jegyzőkönyvek: 1919. augusztus 16." (in Hungarian). DigitArchiv. p. 12. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ "A Magyar Köztársaság miniszterelnökének 1. számu rendelete a sajtótermékekről" (in Hungarian). hu.wikisource.org. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ "A Magyar Köztársaság kormányának 4072/1919. M. E. számu rendelete a rotációs ujságpapirkészletek bejelentése, zár alá vétele és igénybevétele, valamint forgalombahozatala tárgyában" (in Hungarian). hu.wikisource.org. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ Raffay, Ernő (1990). Trianon titkai, avagy hogyan bántak el országunkkal.. (in Hungarian). Budapest: Tornado Damenia Kft. p. 125. ISBN 963-02-7639-9.

- ↑ "A magyar népköztársaság kormányának 3923/1919. M. E. számu rendelete a műtárgyak kivitelének megtiltásáról" (in Hungarian). hu.wikisource.org. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ "A magyar népköztársaság kereskedelemügyi miniszterének 70762/1919. K. M. számu rendelete a Malomüzemi Központ megszüntetéséről" (in Hungarian). hu.wikisource.org. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ Romsics, Ignác (2004). Magyarország története a XX. században (in Hungarian). Budapest: Osiris Kiadó. p. 123. ISBN 963-389-590-1.

- ↑ Romsics, Ignác (2004). Magyarország története a XX. században (in Hungarian). Budapest: Osiris Kiadó. p. 132. ISBN 963-389-590-1.

- ↑ "Minisztertanácsi jegyzőkönyvek: 1919. augusztus 3." (in Hungarian). DigitArchiv. p. 6. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ "Die amtliche Meldung über den Rücktritt" (in German). Neue Freie Presse, Morgenblatt. 1919-08-24. p. 2.

Further reading

- Richard Overy. History of the 20th Century, The Times, Mapping History. London, 2003

- Peter Rokai; Zoltan Đere; Tibor Pal; Aleksandar Kasaš. Istorija Mađara. Beograd, 2002

- András Siklós. "Revolution in Hungary and the Dissolution of the Multinational State. 1918", Studia Historica, Vol. 189. Budapest: Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 1988

External links

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies document "Hungary" by Stephen R. Burant.

Coordinates: 47°29′N 19°02′E / 47.483°N 19.033°E

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies document "Hungary" by Stephen R. Burant.

Coordinates: 47°29′N 19°02′E / 47.483°N 19.033°E

.svg.png)

.svg.png)