Inulin

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| 9005-80-5 | |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL1201646 |

| DrugBank | DB00638 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.701 |

| PubChem | 24763 |

| UNII | JOS53KRJ01 |

| Properties | |

| C6nH10n+2O5n+1 | |

| Molar mass | Polymer; depends on n |

| Pharmacology | |

| V04CH01 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Inulins are a group of naturally occurring polysaccharides produced by many types of plants,[1] industrially most often extracted from chicory.[2] The inulins belong to a class of dietary fibers known as fructans. Inulin is used by some plants as a means of storing energy and is typically found in roots or rhizomes. Most plants that synthesize and store inulin do not store other forms of carbohydrate such as starch. Using inulin to measure renal function is the "gold standard" for comparison with other means of estimating creatinine clearance.[3]

Origin and history

Inulin is a natural storage carbohydrate present in more than 36,000 species of plants, including wheat, onion, bananas, garlic, asparagus, Jerusalem artichoke and chicory. For these plants, inulin is used as an energy reserve and for regulating cold resistance.[4][5] Because it is soluble in water, it is osmotically active. The plants can change the osmotic potential of cells by changing the degree of polymerization of inulin molecules with hydrolysis. By changing osmotic potential without changing the total amount of carbohydrate, plants can withstand cold and drought during winter periods.[6]

Inulin was discovered in 1804 by German scientist Valentin Rose. He found “a peculiar substance” from Inula helenium roots by boiling water extraction.[6] The substance was named inulin because of I. helenium, but it is also called helenin, alatin, and meniantin. Indigestible polysaccharides were of great scientific concern in the beginning of the 20th century.[7] Irvine used chemical methods like methylation to study the molecular structure of inulin, and designed the isolation method for this new anhydrofructose.[7][8] During studies of renal tubules in the 1930s, researchers searched for a substance that can serve as a biomarker that is not reabsorbed or secreted after introduction into tubules.[9][10] Richards introduced inulin because of its high molecular weight and its resistance to enzymes.[9] Today, inulin is used as an active ingredient for functional foods,[5] and it is also used to determine the glomerular filtration rate.[11]

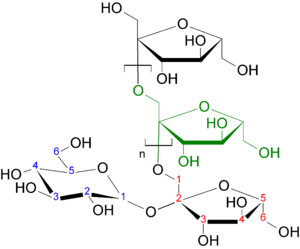

Chemical structure and properties

Inulin is a heterogeneous collection of fructose polymers. It consists of chain-terminating glucosyl moieties and a repetitive fructosyl moiety,[12] which are linked by β(2,1) bonds. The degree of polymerization (DP) of standard inulin ranges from 2 to 60. After removing the fractions with DP lower than 10 during manufacturing process, the remaining product is high performance inulin.[4][5] Some articles considered the fractions with DP lower than 10 as short-chained fructooligosaccharides, and only called the longer-chained molecules inulin.[6]

Because of the β(2,1) linkages, inulin is not digested by enzymes in the human alimentary system, contributing to its functional properties: reduced calorie value, dietary fiber and prebiotic effects. Without color and odor, it has little impact on sensory characteristics of food products. Oligofructose has 35% of the sweetness of sucrose, and its sweetening profile is similar to sugar. Standard inulin is slightly sweet, while high performance inulin is not. Its solubility is higher than the classical fibers. When thoroughly mixed with liquid, inulin forms a gel and a white creamy structure, which is similar to fat. Its three-dimensional gel network, consisting of insoluble submicron crystalline inulin particles, immobilizes large amount of water, assuring its physical stability.[13] It can also improve the stability of foams and emulsions.[5]

Uses

Processed foods

Inulin is increasingly used in processed foods because it has unusually adaptable characteristics. Its flavour ranges from bland to subtly sweet (about 10% of the sweetness of sugar/sucrose). It can be used to replace sugar, fat, and flour. This is advantageous because inulin contains 25-35% of the food energy of carbohydrates (starch, sugar).[14][15] In addition to being a versatile ingredient, inulin has many health benefits. It increases calcium absorption[16] and possibly magnesium absorption,[17] while promoting the growth of beneficial intestinal bacteria. Chicory inulin is reported to increase absorption of calcium in young women with lower calcium absorption[18] and in young men.[1] In terms of nutrition, it is considered a form of soluble fiber and is sometimes categorized as a prebiotic. Conversely, it is also considered a FODMAP, a class of carbohydrates which are rapidly fermented in the colon producing gas and drawing water into the colon which is a problem for individuals with irritable bowel syndrome. The consumption of large quantities (in particular, by sensitive or unaccustomed individuals) can lead to gas and bloating, and products that contain inulin will sometimes include a warning to add it gradually to one's diet.

Due to the body's limited ability to process fructans, inulin has minimal increasing impact on blood sugar. It is considered suitable for diabetics and potentially helpful in managing blood sugar-related illnesses.

Industrial use

Nonhydrolyzed inulin can also be directly converted to ethanol in a simultaneous saccharification and fermentation process, which may have great potential for converting crops high in inulin into ethanol for fuel.[19]

Medical

Inulin and its analog sinistrin are used to help measure kidney function by determining the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which is the volume of fluid filtered from the renal (kidney) glomerular capillaries into the Bowman's capsule per unit time.[20] Inulin is of particular use as it is not secreted or reabsorbed in any appreciable amount at the nephron, allowing GFR to be calculated. However, due to clinical limitations, inulin and sinistrin, although characterised by better handling features, are rarely used for this purpose and creatinine values are the standard for determining an approximate GFR.

Inulin enhances the growth and activities of bacteria or inhibits growth or activities of certain pathogenic bacteria.[21]

Results of human studies are controversial. A study of healthy young men showed reduction for triglycerides and cholesterol individually.[22] However, no differences of triglycerides and cholesterol were seen in a study on 64 young women.[23]

Inulin received no-objection status as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) from the US Food and Drug Administration,[24] including long-chain inulin as GRAS.[25]

Diet

The side effects of inulin dietary fiber diet which may occur in sensitive persons are:[26]

- Intestinal discomfort, including flatulence, bloating, stomach noises, belching, and cramping

- Diarrhea

- Anaphylactic allergic reaction (rare) - inulin is used for GFR testing, and in some isolated cases has resulted in an allergic reaction, possibly linked to a food allergy response.[27]

Biochemistry

Inulins are polymers composed mainly of fructose units, and typically have a terminal glucose. The fructose units in inulins are joined by a β(2→1) glycosidic bond. In general, plant inulins contain between 20 and several thousand fructose units. Smaller compounds are called fructooligosaccharides, the simplest being 1-kestose, which has 2 fructose units and 1 glucose unit.

Inulins are named in the following manner, where n is the number of fructose residues and py is the abbreviation for pyranosyl:

- Inulins with a terminal glucose are known as alpha-D-glucopyranosyl-[beta-D-fructofuranosyl](n-1)-D-fructofuranosides, abbreviated as GpyFn.

- Inulins without glucose are beta-D-fructopyranosyl-[D-fructofuranosyl](n-1)-D-fructofuranosides, abbreviated as FpyFn.

Hydrolysis of inulins may yield fructooligosaccharides, which are oligomers with a degree of polymerization (DP) of <= 10.

Calculation of glomerular filtration rate

Inulin is uniquely treated by nephrons in that it is completely filtered at the glomerulus but neither secreted nor reabsorbed by the tubules. This property of inulin allows the clearance of inulin to be used clinically as a highly accurate measure of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) — the rate of plasma from the afferent arteriole that is filtered into Bowman's capsule measured in mL/min.

It is informative to contrast the properties of inulin with those of para-aminohippuric acid (PAH). PAH is partially filtered from plasma at the glomerulus and not reabsorbed by the tubules, in a manner identical to inulin. PAH is different from inulin in that the fraction of PAH that bypasses the glomerulus and enters the nephron's tubular cells (via the peritubular capillaries) is completely secreted. Renal clearance of PAH is thus useful in calculation of renal plasma flow (RPF), which empirically is (1-hematocrit) times renal blood flow. Of note, the clearance of PAH is reflective only of RPF to portions of the kidney that deal with urine formation, and, thus, underestimates the actual RPF by about 10%.[28]

The measurement of GFR by inulin or sinistrin is still considered the gold-standard. However, it has now been largely replaced by other, simpler measures that are approximations of GFR. These measures, which involve clearance of such substrates as EDTA, iohexol, Cystatin C, 125I-iothalamate (sodium radioiothalamate), the chromium radioisotope 51Cr (chelated with EDTA), and creatinine, have had their utility confirmed in large cohorts of patients with chronic kidney disease.

For both inulin and creatinine, the calculations involve concentrations in the urine and in the serum. However, unlike creatinine, inulin is not naturally present in the body. This is an advantage of inulin (because the amount infused will be known) and a disadvantage (because an infusion is necessary.)

Metabolism in vivo

Inulin is indigestible by the human enzymes ptyalin and amylase, which are adapted to digest starch. As a result, inulin passes through much of the digestive system intact. It is only in the colon that bacteria metabolise inulin, with the release of significant quantities of carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and/or methane. Inulin-containing foods can be rather gassy, in particular for those unaccustomed to inulin, and these foods should be consumed in moderation at first.

Inulin is a soluble fiber, one of three types of dietary fiber including soluble, insoluble, and resistant starch. Soluble fiber dissolves in water to form a gelatinous material. Some soluble fibers may help lower blood cholesterol and glucose levels.

Because normal digestion does not break inulin down into monosaccharides, it does not elevate blood sugar levels and may, therefore, be helpful in the management of diabetes. Inulin also stimulates the growth of bacteria in the gut.[4] Inulin passes through the stomach and duodenum undigested and is highly available to the gut bacterial flora. This makes it similar to resistant starches and other fermentable carbohydrates.

Some traditional diets contain over 20 g per day of inulin or fructooligosaccharides. The diet of the prehistoric hunter-forager in the Chihuahuan Desert has been estimated to include 135 g per day of inulin-type fructans.[29] Many foods naturally high in inulin or fructooligosaccharides, such as chicory, garlic, and leek, have been seen as "stimulants of good health" for centuries.[30]

Natural sources

Plants that contain high concentrations of inulin include:

- Agave (Agave spp.)

- Banana/Plantain (Musaceae)

- Burdock (Arctium lappa)

- Camas (Camassia spp.)

- Chicory (Cichorium intybus)

- Coneflower (Echinacea spp.)

- Costus (Saussurea lappa)

- Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

- Elecampane (Inula helenium)

- Garlic (Allium sativum)

- Globe artichoke (Cynara scolymus, Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus)

- Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

- Jicama (Pachyrhizus erosus)

- Leopard's-bane (Arnica montana)

- Mugwort Root (Artemisia vulgaris)

- Onion (Allium cepa)

- Wild yam (Dioscorea spp.)

- Yacón (Smallanthus sonchifolius spp.)

References

- 1 2 Roberfroid, M. B. (2003). "Introducing inulin-type fructans". Br. J. Nutr. 93: 13–26. doi:10.1079/bjn20041350. PMID 15877886.

- ↑ Roberfroid MB (2007). "Inulin-type fructans: functional food ingredients". Journal of Nutrition. 137 (11 suppl): 2493S–2502S. PMID 17951492.

- ↑ Hsu, CY; Bansal, N (August 2011). "Measured GFR as "gold standard"--all that glitters is not gold?". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 6 (8): 1813–4. doi:10.2215/cjn.06040611. PMID 21784836.

- 1 2 3 Niness, KR (July 1999). "Inulin and oligofructose: what are they?". The Journal of Nutrition. 129 (7 Suppl): 1402S–6S. PMID 10395607.

- 1 2 3 4 Kalyani Nair, K.; Kharb, Suman; Thompkinson, D. K. (18 March 2010). "Inulin Dietary Fiber with Functional and Health Attributes—A Review". Food Reviews International. 26 (2): 189–203. doi:10.1080/87559121003590664.

- 1 2 3 Boeckner, LS; Schnepf, MI; Tungland, BC (2001). "Inulin: a review of nutritional and health implications.". Advances in Food and Nutrition Research. 43: 1–63. doi:10.1016/s1043-4526(01)43002-6. PMID 11285681.

- 1 2 Irvine, James Colquhoun; Soutar, Charles William (1920). "CLXV. The constitution of polysaccharides. Part II. The conversion of cellulose into glucose". Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions. 117: 1489. doi:10.1039/CT9201701489.

- ↑ Irvine, James Colquhoun; Stevenson, John Whiteford (July 1929). "The molecular structure of inulin. Isolation of a new anhydrofructose.". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 51 (7): 2197–2203. doi:10.1021/ja01382a035.

- 1 2 Richards, A. N.; Westfall, B. B.; Bott, P. A. (1 October 1934). "Renal Excretion of Inulin, Creatinine and Xylose in Normal Dogs". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 32 (1): 73–75. doi:10.3181/00379727-32-7564P.

- ↑ Shannon, JA; Smith, HW (July 1935). "The excretion of inulin, xylose and urea by normal and phlorinzinized man". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 14 (4): 393–401. doi:10.1172/JCI100690. PMID 16694313.

- ↑ Coulthard, MG; Ruddock, V (February 1983). "Validation of inulin as a marker for glomerular filtration in preterm babies.". Kidney International. 23 (2): 407–9. doi:10.1038/ki.1983.34. PMID 6842964.

- ↑ Barclay, Thomas, et al. Inulin-a versatile polysaccharide with multiple pharmaceutical and food chemical uses. Diss. International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council, 2010.

- ↑ Franck, A. (9 March 2007). "Technological functionality of inulin and oligofructose". British Journal of Nutrition. 87 (S2): S287. doi:10.1079/BJN/2002550.

- ↑ "Caloric value of inulin and oligofructose"

- ↑ "Caloric Value of Inulin and Oligofructose"

- ↑ Abrams S, Griffin I, Hawthorne K, Liang L, Gunn S, Darlington G, Ellis K (2005). "A combination of prebiotic short- and long-chain inulin-type fructans enhances calcium absorption and bone mineralization in young adolescents". Am J Clin Nutr. 82 (2): 471–6. PMID 16087995.

- ↑ Coudray C, Demigné C, Rayssiguier Y (2003). "Effects of dietary fibers on magnesium absorption in animals and humans". J Nutr. 133 (1): 1–4. PMID 12514257.

- ↑ Griffin, I. J.; P. M. . Hicks; R. P. Heaney; S. A. Abrams (2003). "Enriched chicory inulin increases calcium absorption mainly in girls with lower calcium absorption". Nutr. Res. 23: 901–909. doi:10.1016/s0271-5317(03)00085-x.

- ↑ Kazuyoshi Ohta; Shigeyuki Hamada; Toyohiko Nakamura (1992). "Production of High Concentrations of Ethanol from Inulin by Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation Using Aspergillus niger and Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 59 (3): 729–733. PMC 202182

. PMID 8481000.

. PMID 8481000. - ↑ Physiology: 7/7ch04/7ch04p11 - Essentials of Human Physiology - "Glomerular Filtration Rate"

- ↑ Saad, N.; C. Delattre; M. Urdaci; J. M. Schmitter; P. Bressollier (2013). "An overview of the last advances in probiotic and prebiotic field". LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 50: 1–16.

- ↑ Cho, S. S. (2009). Handbook of prebiotics and probiotics ingredients: health benefits and food applications. CRC Press.

- ↑ Pedersen, Anette; Sandström, Brittmarie; Van Amelsvoort, Johan M. M. (1997). "The effect of ingestion of inulin on blood lipids and gastrointestinal symptoms in healthy females". British Journal of Nutrition. 78 (2): 215–222. doi:10.1079/bjn19970141.

- ↑ Rulis, Alan M (5 May 2003). "Agency Response Letter GRAS Notice No. GRN 000118". US Food and Drug Administration.

- ↑ Keefe, Dennis M (9 December 2015). "Agency Response Letter GRAS Notice No. GRN 000576". US Food and Drug Administration.

- ↑ Coussement, Paul AA. "Inulin and oligofructose: safe intakes and legal status." The Journal of nutrition 129.7 (1999): 1412S-1417s.

- ↑ "'Renal hypersensitivity' to inulin and IgA nephropathy". Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ↑ Costanzo, Linda. Physiology, 4th Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2007. Page 156-160.

- ↑ Leach, JD; Sobolik, KD (2010). "High dietary intake of prebiotic inulin-type fructans in the prehistoric Chihuahuan Desert.". Br J Nutr. 103 (11): 1558–61. doi:10.1017/S0007114510000966. PMID 20416127.

- ↑ Coussement P (1999). "Inulin and oligofructose: safe intakes and legal status". J Nutr. 129 (7 Suppl): 1412S–7S. PMID 10395609. Text