Johnstown (city), New York

| Johnstown, New York | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Johnson Hall, home of Sir William Johnson, New York State Historic Site | |

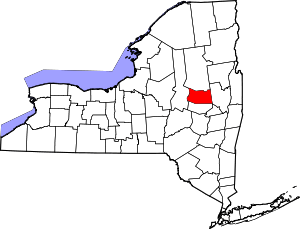

Johnstown Location within the state of New York | |

| Coordinates: 43°0′26″N 74°22′20″W / 43.00722°N 74.37222°WCoordinates: 43°0′26″N 74°22′20″W / 43.00722°N 74.37222°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Fulton |

| Settled | 1758 |

| Incorporated |

1803 (village) 1895 (city) |

| Founded by | Sir William Johnson |

| Government | |

| • Type | (Mayor-Council) |

| • Mayor | Michael Julius (D) |

| • Common Council |

Members' List

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.88 sq mi (12.65 km2) |

| • Land | 4.88 sq mi (12.63 km2) |

| • Water | 0.008 sq mi (0.02 km2) |

| Elevation | 673 ft (205 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 8,743 |

| • Density | 1,793/sq mi (692.4/km2) |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC-5) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) |

| ZIP code | 12095 |

| Area code(s) | 518 |

| FIPS code | 36-38781 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0954147 |

| Website |

cityofjohnstown |

Johnstown is a city and the county seat of Fulton County in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2010 Census, the city had population of 8,743.[1] The city was named after its founder, Sir William Johnson.[2]

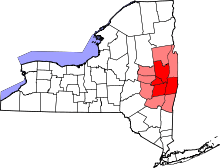

The city of Johnstown is mostly surrounded by the town of Johnstown, of which it was once a part when it was a village. Also adjacent to the city is the city of Gloversville. The two cities are together known as the "Glove Cities". They are known for their history of specialty manufacturing. Johnstown is located approximately 45 miles (72 km) west of Albany, about one-third of the way between Albany and the Finger Lakes region to the west.

History

Early colonial history

Johnstown, originally "John's Town", was founded in 1762 by Sir William Johnson, a Baronet who named it after his son John Johnson.[3] William Johnson came to the British colony of New York from Ireland in 1732.[4] He was a trader who learned American Indian languages and culture, forming close relationships with many Native American leaders. He was appointed as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, as well as a major general in the British forces during the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War). His alliances with the Iroquois were significant to the war.

As a reward for his services, Johnson received large tracts of land in what are now Hamilton and Fulton counties. He established Johnstown and became one of New York's most prosperous and influential citizens. He was the largest landowner in the Mohawk Valley, with an estate of more than 400,000 acres (1,600 km2) before his death. Having begun as an Indian trader, he expanded his business interests to include a sawmill and lumber business, and a flour mill that served the area. Johnson, the largest slaveholder in the county and perhaps in the state of New York, had some 60 enslaved Africans working these businesses. He also recruited many Scots-Irish tenant farmers to work his lands.[5] Observing Johnson's successful business endeavors, the local Native American inhabitants dubbed him Warragghivagey, or "he who does much business."[6]

.jpg)

As the area initially owned and settled by Johnson grew, he convinced the governor, Lord William Tryon, to establish a new county in upstate New York west of Albany County. This new county was named Tryon, after the governor, and Johnstown was made the county seat.[4] The county courthouse, built by William Johnson in Johnstown in 1772, partly at his own expense, still stands today, as the oldest operating courthouse in New York.[7] Sir William Johnson died in 1774 before the American colonies declared their independence from Britain.

Revolutionary War and aftermath

Although the majority of the fighting during the American Revolution raged elsewhere, Johnstown did see its share of fighting late in the war. With area residents not knowing of Cornwallis' defeat and surrender at the Battle of Yorktown in Virginia, about 1,400 soldiers fought at the Battle of Johnstown, one of the last battles of the American Revolution, on October 25, 1781. The Continental forces, led by Col. Marinus Willett of Johnstown, ultimately put the British to flight.[8] During that time, many British Loyalists fled both Johnstown and the surrounding area for Canada, including Johnson's surviving family. Sir William Johnson's home suffered vandalism at the hands of Continental soldiers quartered there.[9]

After the American Revolution, Johnstown became part of Montgomery County when the name of Tryon County was changed to honor the Continental General Richard Montgomery, who died at the Battle of Quebec. All of the Johnson property was forfeited to the state because of the family's Loyalist sentiments and support for the British cause. Sir William Johnson's manor house and estate were subsequently purchased by Silas Talbot, a naval officer and hero of the American Revolution.

19th century to the present

In 1803 the community of Johnstown was incorporated as a village. In 1838, Johnstown's county affiliation changed yet again when what by then remained of Mongomery County was divided into two separate counties: Montgomery and Fulton. While the village of Fonda became the new county seat of Montgomery County, Johnstown became the county seat of Fulton County. The village of Johnstown became a city in 1895, becoming separate from the surrounding town.

In 1889, shortly after the Johnstown Flood in Pennsylvania, Johnstown New York suffered a similarly devastating flood. Cayadutta Creek rampaged, Schreiber's Skin Mill was swept away, as was the State Street bridge, and over twenty people were drowned or missing when the flood carried away the Perry Street bridge.

Johnson Hall was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960. It is operated by New York State as an historic site, with regularly scheduled special events.

Notable people

Silas Talbot

Silas Talbot moved with his family to Johnstown, where he purchased Sir William Johnson's estate and manor house. A hero of the American Revolution, he later served as a member of the New York Assembly (1792–1793) and as a congressman in the U.S. House of Representatives (1793–1794) from that district.

In 1797 he supervised the building of the USS Constitution ("Old Iron Sides") at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston, Massachusetts.[10] Talbot commanded the USS Constitution, largely in the West Indies, from 1799 to 1801, when he retired from the U.S. Navy.[11]

Daniel Cady

One of the men instrumental in shaping Fulton County was Judge Daniel Cady, a prominent Johnstown resident. Sometimes called "the father of Fulton County", Cady named the new county after Robert Fulton, who was related by marriage to Cady's wife, Margaret Livingston. Robert Fulton, an inventor, is perhaps best known for devising the improvements that made steamboats commercially viable.[12]

Judge Daniel Cady was one of Johnstown's most important citizens. With indirect connections by marriage to John Jacob Astor and that family's lucrative fur business interests, Daniel Cady, adept at managing these connections and his own business interests, joined the ranks of the wealthiest landowners in New York. After moving to Johnstown in 1799, he married Margaret Livingston, whose father, Col. James Livingston, fought in the Continental Army at the battles of Quebec and Saratoga during the American Revolution. Col. Livingston is credited with frustrating Benedict Arnold's attempted treason by firing on The Vulture, the boat intended to carry Arnold to safety.[13] A public servant as well as astute lawyer and businessman, Judge Cady served in the New York state legislature from 1808 until 1814. In 1814 he was elected as a Federalist to one term in the United States House of Representatives. In 1816, he returned to Johnstown from Washington and resumed his legal practice. He later served as a judge on the New York Supreme Court, Fourth District, from 1847 until 1855. Cady died in Johnstown in 1859 and is buried in the cemetery there.[14]

John D. McDonald

John D. McDonald (1816-1900) was born in Johnstown. He was a farmer and served in the Wisconsin State Assembly in 1870 and 1871.[15]

Israel T. Hatch

Hatch was born in Johnstown. He went on to become mayor of Buffalo, New York, and was also elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. He was law partners with Henry K. Smith, who also became a mayor of Buffalo.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Daniel Cady is today perhaps best known as the father of the prominent women's rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was born in Johnstown in 1815. Stanton, who later worked in partnership with Susan B. Anthony and served for many years as president of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), spent her childhood in Johnstown, where she studied at the Johnstown Academy. It was one of the first schools in New York to receive a teaching certificate issued by the newly formed state education system in the later 19th century.[16] After leaving to continue her education in Troy, New York, Stanton returned to Johnstown with her husband Henry Brewster Stanton, a lawyer and abolitionist who studied law under her father, Daniel Cady.[17] Because of her role, Johnstown, together with Seneca Falls, New York, where Elizabeth Cady Stanton helped organize the first Women's Rights Convention held in 1848, lays claim to being the birthplace of the women's rights movement in the United States.[18] Stanton's speech, the Declaration of Sentiments, given at the Seneca Falls convention and modeled on the Declaration of Independence, is generally credited with instigating the women's suffrage movement in the United States.

Peter Yost

Peter Yost was born in Saxe-Coburg, Germany, in 1740, and was part of the population that fled the German Palatinate when Louis XIV's French armies invaded at the end of the 17th century. He settled in Johnstown where, backed by Sir William Johnson, he became a successful tanner. Peter's descendant Charles Woodruff Yost became one of the 20th century's most important diplomats and was a founder of the United Nations.

Industry in Johnstown

Glove industry and related enterprise

With plentiful forests and the wood bark they produced, Johnstown became a center for tanning of leather during the late 19th century. By the early 20th century Johnstown, along with neighboring Gloversville, became known as the glove-making capital of the world. Nicknamed the "Glove Cities", the two cities are still called that today.[16] Many fringe business once existed to support the glove and leather industries around Johnstown. Box manufacturers, thread dealers, sewing machine repairmen, chemical companies and many others made a living helping to supply and service the industry.[16]

Johnstown and Gloversville were home to numerous glove manufacturing companies and dozens of leather tanners and finishers. Thousands of people were employed by or affiliated with the glove and leather industries, making them a major part of the economic history of the two cities.

Throughout most of the history of the glove industry in Johnstown, most companies used home workers to sew the gloves. Men cut the gloves from leather in factories, and women hand-sewed the gloves at home. Later when the sewing machine was developed, many women moved to the factories to work. Until the last years of the 20th century, home glove workers were still working in the area.

The glove-making industry, together with its related businesses, had its ups and downs. It was directly affected by tax and tariff laws. The tanneries and glove shops flourished during World War II when most of the "Military Black" leather gloves worn by American servicemen were produced in Fulton County. During the last half of the 20th century, however, the cities' economies steadily declined as business was lost to low-wage manufacturing operations overseas. Today countries such as China and the Philippines produce most of the world's gloves. While some companies still remain in the Glove Cities, just a few manufacture their product in the United States. The others use overseas labor to sew gloves. Today only one glove manufacturer is located in Johnstown, while a few operate in Gloversville.

Although the leather industry has declined, some local companies have survived by developing leather products suited to niche markets. The remaining businesses concentrate on one or two types of leather. They remain ready to adapt to changes in trends. There are still two tanneries operating in Johnstown and a few more in Gloversville. Another handful of state-of-the-art leather finishing facilities can be found there, as well as a dozen or so leather dealers.

Knox Gelatine

One of the early industries to establish itself in Johnstown was the Knox gelatine plant. It was built in 1890 by Charles B. Knox, a prominent Johnstown resident, who developed the granulated, unflavored gelatin still used in food preparation today.[19][20] When Knox died in 1908, his wife Rose Knox assumed management of the business. She became one of the earliest successful American businesswomen. The Knox family and its philanthropic foundation were generous to the city. Results of their philanthropy can still be found there today. They gave the city the block of land known as Knox Field, where the playgrounds, athletic fields, and bridle path are located. Knox Junior High School was named in honor of the family. The Knox Gelatin plant, once a major employer in Johnstown, closed in 1975 following the sale of the company to the Lipton Tea Company.[21]

Geography

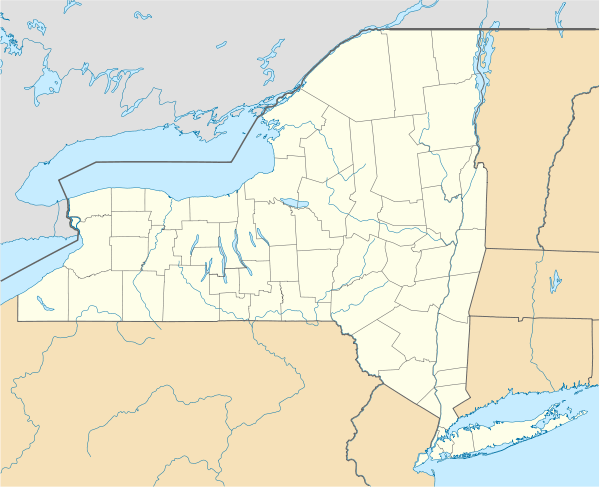

Johnstown is located along the southern edge of Fulton County, in the picturesque Mohawk Valley of upstate New York. It is slightly north of the route developed for the Erie Canal through what is now Montgomery County. Although not a hilltown, Johnstown is close to the Adirondack Mountains that stretch across the northern portion of Fulton County. It is situated near the southern border of the Adirondack Park.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 4.88 square miles (12.65 km2), of which 4.88 square miles (12.63 km2) is land and 0.01 square miles (0.02 km2), or 0.17%, is water.[1] The city is bordered to the north, east, and west by the town of Johnstown, to the northeast by the city of Gloversville, and to the south by the town of Mohawk in Montgomery County.

Cayadutta Creek which runs through the city provided water power needed to generate the electricity required by the various industries that grew up in Johnstown.[22] The creek flows south to join the Mohawk River at Fonda.

East-west highways, New York State Route 29 and New York State Route 67, intersect in the city and also cross the north-south highway New York State Route 30A. NY 29 leads east 32 miles (51 km) to Saratoga Springs and northwest 8 miles (13 km) to Rockwood. NY 67 leads southeast 11 miles (18 km) to Amsterdam and west 18 miles (29 km) to St. Johnsville. NY 30A leads northeast 4 miles (6 km) to Gloversville and 10 miles (16 km) to Mayfield, as well as south 4.5 miles (7.2 km) to Fonda and 6 miles (10 km) to the New York Thruway.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 3,282 | — | |

| 1880 | 5,013 | 52.7% | |

| 1890 | 7,768 | 55.0% | |

| 1900 | 10,130 | 30.4% | |

| 1910 | 10,447 | 3.1% | |

| 1920 | 10,908 | 4.4% | |

| 1930 | 10,801 | −1.0% | |

| 1940 | 10,666 | −1.2% | |

| 1950 | 10,923 | 2.4% | |

| 1960 | 10,390 | −4.9% | |

| 1970 | 10,045 | −3.3% | |

| 1980 | 9,360 | −6.8% | |

| 1990 | 9,058 | −3.2% | |

| 2000 | 8,511 | −6.0% | |

| 2010 | 8,743 | 2.7% | |

| Est. 2015 | 8,345 | [23] | −4.6% |

As of the census[25] of 2000, there were 8,511 people, 3,579 households, 2,208 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,751.1 people per square mile (676.2/km²). There were 3,979 housing units at an average density of 818.7 per square mile (316.1/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 96.57% White, 0.62% Black or African American, 0.32% Native American, 0.99% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.41% from other races, and 1.06% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.08% of the population.

There were 3,579 households out of which 29.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.1% were married couples living together, 13.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.3% were non-families. 33.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 16.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 2.91.

In the city the population was spread out with 24.4% under the age of 18, 7.2% from 18 to 24, 27.6% from 25 to 44, 21.6% from 45 to 64, and 19.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females there were 87.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 82.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $32,603, and the median income for a family was $39,909. Males had a median income of $30,636 versus $22,272 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,324. About 9.3% of families and 13.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.5% of those under age 18 and 8.2% of those age 65 or over.

Footnotes

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), Johnstown city, New York". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 170.

- ↑ Decker, back cover

- 1 2 Decker, p.7

- ↑ Williams-Myers, p. 24; 29-30

- ↑ Decker, p. 29

- ↑ Decker, p.8

- ↑ Historic Johnstown, New York (Battle of Johnstown)

- ↑ Decker pp 32-33; 116

- ↑ Mystic Seaport Library (Silas Talbot); Decker p. 31

- ↑ Mystic Seaport Library (Silas Talbot)

- ↑ Decker, p 33

- ↑ Griffith, p 4

- ↑ Griffith, p 5

- ↑ Wisconsin Blue Book 1871, "Biographical Sketch of John D. McDonald", pg. 386

- 1 2 3 Decker

- ↑ Griffith

- ↑ Decker, pp 16 & 33

- ↑ "Charles B Knox Gelatine Co. Inc. Edition of The Old Mohawk-Turnpike Book". Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Knox® History". Retrieved June 9, 2016.

More than one hundred years since the brand was first introduced, Knox® Unflavoured Gelatine is still as timely as ever.

- ↑ Decker, pp 53-66

- ↑ Decker, p. 66

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

References

- Decker, Lewis G. Images of America: Johnstown. Arcadia Publishing (an imprint of Tempus Publishing, Inc.); Charlestown, SC. 1999. ISBN 0-7385-0174-3.

- Griffith, Elizabeth. In Her Own Right: The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Oxford University Press; New York, NY. 1984. ISBN 0-19-503729-4.

- Historic Johnstown, New York, accessed September 19, 2006.

- Mystic Seaport Library; Manuscripts Collection (Silas Talbot) accessed September 19, 2006.

- Williams-Myers, A.J. Long Hammering: Essays on the Forging of an African American Presence in the Hudson River Valley to the Early Twentieth Century. Africa World Press, Inc.; Trenton, NJ. 1994. ISBN 0-86543-303-8.

External links

- City of Johnstown official website

- "Glovers, Tanners & Leather Dressers of Fulton County, New York"

- Fulton-Montgomery Photographic Archives

- Fulton County Historical Society & Museum

- Darci's Place (Biography of Charles Knox, founder of Knox Gelatin in Johnstown, NY)

- "Battle of Johnstown", Historic Johnstown, New York

- "Rose Knox, First Lady of Johnstown", Historic Johnstown, New York

- Revolutionary Day (narrative and walking tour of historic sites of the American Revolutionary period in Johnstown, NY)

- "Sir William Johnson & Johnson Hall", Historic Johnstown

- "Steam Engine Library" (biography of Robert Fulton), University of Rochester