Lactose intolerance

| Lactose intolerance | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | lactase deficiency, hypolactasia |

| |

| Lactose which is made up of two simple sugars | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| ICD-10 | E73 |

| ICD-9-CM | 271.3 |

| OMIM | 223100 150220 |

| DiseasesDB | 7238 |

| MedlinePlus | 000276 |

| eMedicine | med/3429 ped/1270 |

| Patient UK | Lactose intolerance |

| MeSH | D007787 |

Lactose intolerance is a condition in which people have symptoms due to the decreased ability to digest lactose, a sugar found in milk products. Those affected vary in the amount of lactose they can tolerate before symptoms develop. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, gas, and nausea. These typically start between half and two hours after drinking milk. Severity depends on the amount a person eats or drinks.[1] It does not cause damage to the gastrointestinal tract.[2]

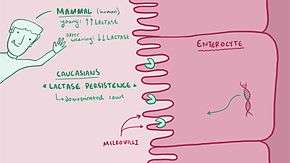

Lactose intolerance is due to not enough of the enzyme lactase in the small intestines to break lactose down into glucose and galactose.[3] There are four types: primary, secondary, developmental, and congenital. Primary lactose intolerance is when the amount of lactase decline as people age. Secondary lactose intolerance is due to injury to the small intestine such as from infection, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or other diseases.[1][4] Developmental lactose intolerance may occur in premature babies and usually improves over a short period of time. Congenital lactose intolerance is an extremely rare genetic disorder in which little or no lactase is made from birth.[1]

Diagnosis may be confirmed if symptoms resolve following eliminating lactose from the diet. Other supporting tests include a hydrogen breath test and a stool acidity test. Other conditions that may produce similar symptoms include irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.[1] Lactose intolerance is different from a milk allergy. Management is typically by decreasing the amount of lactose in the diet or taking lactase supplements.[1] Those affected are usually able to drink at least one cup of milk without developing significant symptoms, with greater amounts tolerated if drunk with a meal or throughout the day.[1][5]

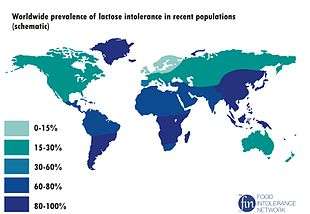

The number of people with lactose intolerance is unknown.[6] The percentage of the population that has a decrease in lactase as they age is less than 10% in Northern Europe and as high as 95% in parts of Asia and Africa.[3] Onset is typically in late childhood or adulthood.[1] The ability to digest lactose into adulthood is believed to have developed among some human populations in the last 10,000 years.[3][7]

Terminology

Lactose intolerance primarily refers to a syndrome having one or more symptoms upon the consumption of food substances containing lactose. Individuals may be lactose intolerant to varying degrees, depending on the severity of these symptoms. "Lactose malabsorption" refers to the physiological concomitant of lactase deficiency (i.e., the body does not have sufficient lactase capacity to digest the amount of lactose ingested).[2] Hypolactasia (lactase deficiency) is distinguished from alactasia (total lack of lactase), a rare congenital defect.

Lactose intolerance is not an allergy, because it is not an immune response, but rather a sensitivity to dairy caused by lactase deficiency. Milk allergy, occurring in only 4% of the population, is a separate condition, with distinct symptoms that occur when the presence of milk proteins trigger an immune reaction.[8]

Signs and symptoms

The principal symptom of lactose intolerance is an adverse reaction to products containing lactose (primarily milk), including abdominal bloating and cramps, flatulence, diarrhea, nausea, borborygmi, and vomiting (particularly in adolescents). These appear one-half to two hours after consumption.[1] The severity of symptoms typically increases with the amount of lactose consumed; most lactose-intolerant people can tolerate a certain level of lactose in their diets without ill effects.[9][10]

Primary congenital alactasia

Primary congenital alactasia, or congenital lactase deficiency (CLD), where the production of lactase is inhibited from birth, can be dangerous in any society because of infants' initial reliance on human breast milk for nutrition until they are weaned onto other foods. Before the 20th century, babies born with CLD often did not survive,[2] but death rates decreased with soybean-derived infant formulas and manufactured lactose-free dairy products.[11]

Causes

Lactose intolerance is a consequence of lactase deficiency, which may be genetic (primary hypolactasia and primary congenital alactasia) or environmentally induced (secondary or acquired hypoalactasia). In either case, symptoms are caused by insufficient levels of lactase in the lining of the duodenum. Lactose, a disaccharide molecule found in milk and dairy products, cannot be directly absorbed through the wall of the small intestine into the bloodstream, so, in the absence of lactase, passes intact into the colon. Bacteria in the colon can metabolise lactose, and the resulting fermentation produces copious amounts of gas (a mixture of hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane) that causes the various abdominal symptoms. The unabsorbed sugars and fermentation products also raise the osmotic pressure of the colon, causing an increased flow of water into the bowels (diarrhea).[12][13] The LCT gene provides the instructions for making lactase. The specific DNA sequence in the MCM6 gene helps control whether the LCT gene is turned on or off.[14] At least several thousand years ago, some humans developed a mutation in the MCM6 gene that keeps the LCT gene turned on even after breast feeding is stopped.[15] People who are lactose intolerant do not have this mutation. The LCT and MCM6 genes are both located on the long arm (q) of chromosome 2 in region 21. The locus can be expressed as 2q21.[15] The lactase deficiency also could be linked to certain heritages. Seventy-five percent of all African American, Jewish, Mexican American, and Native American adults are lactose intolerant.[16] Analysis of the DNA of 94 ancient skeletons in Europe and Russia concluded that the lactose tolerant mutation appeared about 4,300 years ago and spread throughout the European population.[17]

Some human populations have developed lactase persistence, in which lactase production continues into adulthood probably as a response to the benefits of being able to digest milk from farm animals.[3] Some have argued that this links intolerance to natural selection favoring lactase-persistent individuals, but it is also consistent with a physiological response to decrease lactase production when it is not needed in cultures in which dairy products are not an available food source.[18] Although populations in Europe, India, Arabia, and Africa were first thought to have high rates of lactase persistence because of a single mutation, lactase persistence has been traced to a number of mutations that occurred independently.[19]

Different alleles for lactase persistence have developed at least three times in East African populations, with persistence extending from 26% in Tanzania to 88% in the Beja pastoralist population in Sudan.[20]

Lactose intolerance is classified according to its causes as:

Primary hypolactasia

Primary hypolactasia, or primary lactase deficiency, is genetic, only affects adults, and is caused by the absence of a lactase persistence allele. In individuals without the lactase persistence allele, less lactase is produced by the body over time, leading to hypolactasia in adulthood.[2][21] The frequency of lactase persistence, which allows lactose tolerance, varies enormously worldwide, with the highest prevalence in Northwestern Europe, declines across southern Europe and the Middle East and is low in Asia and most of Africa, although it is common in pastoralist populations from Africa.[3][22]

Secondary hypolactasia

Secondary hypolactasia or secondary lactase deficiency, also called acquired hypolactasia or acquired lactase deficiency, is caused by an injury to the small intestine. This form of lactose intolerance can occur in both infants and lactase persistent adults and is generally reversible.[23] It may be caused by acute gastroenteritis, coeliac disease, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis,[24] chemotherapy, intestinal parasites (such as giardia), or other environmental causes.[2][25][26][27][28]

Primary congenital alactasia

Primary congenital alactasia, also called congenital lactase deficiency, is an extremely rare, autosomal recessive enzyme defect that prevents lactase expression from birth.[2][3] People with congenital lactase deficiency cannot digest lactose from birth, so cannot digest breast milk. This genetic defect is characterized by a complete lack of lactase (alactasia). About 40 cases have been reported worldwide, mainly limited to Finland.[3]

Diagnosis

To assess lactose intolerance, intestinal function is challenged by ingesting more dairy products than can be readily digested. Clinical symptoms typically appear within 30 minutes, but may take up to two hours, depending on other foods and activities.[29] Substantial variability in response (symptoms of nausea, cramping, bloating, diarrhea, and flatulence) is to be expected, as the extent and severity of lactose intolerance varies among individuals.

The next step is to determine whether it is due to primary lactase deficiency or an underlying disease that causes secondary lactase deficiency.[2] Physicians should investigate the presence of undiagnosed coeliac disease, Crohn disease, or other enteropathies when secondary lactase deficiency is suspected and an infectious gastroenteritis has been ruled out.[2]

Lactose intolerance is distinct from milk allergy, an immune response to cow's milk proteins. They may be distinguished in diagnosis by giving lactose-free milk, producing no symptoms in the case of lactose intolerance, but the same reaction as to normal milk in the presence of a milk allergy. A person can have both conditions. If positive confirmation is necessary, four tests are available.[30]

Hydrogen breath test

In a hydrogen breath test, the most accurate lactose intolerance test, after an overnight fast, 25 grams of lactose (in a solution with water) are swallowed. If the lactose cannot be digested, enteric bacteria metabolize it and produce hydrogen, which, along with methane, if produced, can be detected on the patient's breath by a clinical gas chromatograph or compact solid-state detector. The test takes about 2.5 hours to complete. If the hydrogen levels in the patient's breath are high, they may have lactose intolerance. This test is not usually done on babies and very young children, because it can cause severe diarrhea.[31]

Blood test

In conjunction, measuring blood glucose level every 10 to 15 minutes after ingestion will show a "flat curve" in individuals with lactose malabsorption, while the lactase persistent will have a significant "top", with a typical elevation of 50% to 100%, within one to two hours. However, due to the need for frequent blood sampling, this approach has been largely replaced by breath testing.

After an overnight fast, blood is drawn and then 50 grams of lactose (in aqueous solution) are swallowed. Blood is then drawn again at the 30-minute, 1-hour, 2-hour, and 3-hour marks. If the lactose cannot be digested, blood glucose levels will rise by less than 20 mg/dl.[32]

Stool acidity test

This test can be used to diagnose lactose intolerance in infants, for whom other forms of testing are risky or impractical.[33] The infant is given lactose to drink. If the individual is tolerant, the lactose is digested and absorbed in the small intestine; otherwise, it is not digested and absorbed, and it reaches the colon. The bacteria in the colon, mixed with the lactose, cause acidity in stools. Stools passed after the ingestion of the lactose are tested for level of acidity. If the stools are acidic, the infant is intolerant to lactose.[34] Stool pH in lactose intolerance is less than 5.5.

Intestinal biopsy

An intestinal biopsy can confirm lactase deficiency following discovery of elevated hydrogen in the hydrogen breath test.[35] Modern techniques have enabled a bedside test, identifying presence of lactase enzyme on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy instruments.[36] However, for research applications such as mRNA measurements, a specialist laboratory is required.

Stool sugar chromatography

Chromatography can be used to separate and identify undigested sugars present in faeces. Although lactose may be detected in the faeces of people with lactose intolerance, this test is not considered reliable enough to conclusively diagnose or exclude lactose intolerance.

Genetic diagnostic

Genetic tests may be useful in assessing whether a person has primary lactose intolerance.[37] Lactase activity persistence in adults is associated with two polymorphisms: C/T 13910 and G/A 22018 located in the MCM6 gene.[38] These polymorphisms may be detected by molecular biology techniques at the DNA extracted from blood or saliva samples; genetic kits specific for this diagnosis are available. The procedure consists of extracting and amplifying DNA from the sample, following with a hybridation protocol in a strip. Colored bands are obtained as final result, and depending on the different combination, it would be possible to determine whether the patient is lactose intolerant. This test allows a noninvasive definitive diagnostic.

Management

When lactose intolerance is due to secondary lactase deficiency, treatment of the underlying disease allows lactase activity to return to normal levels.[39] In people with coeliac disease, lactose intolerance normally revert or improve several months after starting a gluten-free diet, but temporary dietary restriction of lactose may be needed.[4][40]

Lactose intolerance due to primary lactase deficiency is not considered a condition that requires treatment in societies where the diet contains relatively little dairy. However, those living among societies that are largely lactose-tolerant may find lactose intolerance troublesome. Although no way to reinstate lactase production had been found, some individuals have reported their intolerance varies over time, depending on health status and pregnancy.[41] Some lactose-intolerant women may improve the ability to digest lactose during pregnancy. This might be caused by colonic flora changes during pregnancy.[42] Lactose intolerance can also be managed by ingesting live yogurt cultures containing lactobacilli that are able to digest the lactose in other dairy products. This may explain why many South Asians, though genetically lactose intolerant, are able to consume large quantities of milk without many symptoms of lactose intolerance, since consuming live yogurt cultures is very common among the South Asian population.[43] Lactose intolerance is not usually an absolute condition: the reduction in lactase production, and the amount of lactose that can therefore be tolerated, varies from person to person. Since lactose intolerance poses no further threat to a person's health, the condition is managed by minimizing the occurrence and severity of symptoms. Berdanier and Hargrove recognize four general principles in dealing with lactose intolerance — avoidance of dietary lactose, substitution to maintain nutrient intake, regulation of calcium intake and use of enzyme substitute.[35]

Diet

Individuals vary in the amount of lactose they can tolerate.[1] Label reading is essential, as commercial terminology varies according to language and region.[35]

Lactose is present in two large food categories: conventional dairy products, and as a food additive (casein, caseinate, whey), which may contain traces of lactose.

Dairy products

Lactose is a water-soluble substance. Fat content and the curdling process affect tolerance of foods. After the curdling process, lactose is found in the water-based portion (along with whey and casein), but not in the fat-based portion. Dairy products that are "reduced-fat" or "fat-free" generally have slightly higher lactose content. Low-fat dairy foods also often have various dairy derivatives added, such as milk solids, increasing the lactose content.

- Milk

Human milk has a high lactose content, around 9%. Unprocessed cow milk is about 4.7% lactose. Unprocessed milk from other bovids contains a similar fraction of lactose (goat milk 4.7%,[44] buffalo 4.86%,[45] yak 4.93%,[46] sheep 4.6%)

- Butter

The butter-making process separates the majority of milk's water components from the fat components. Lactose, being a water-soluble molecule, will largely be removed, but will still be present in small quantities in the butter unless it is also fermented to produce cultured butter. Clarified butter, however, contains very little lactose and is safe for most lactose-intolerant people.

- Yogurt

People can be more tolerant of traditionally made yogurt than milk, because it contains lactase produced by the bacterial cultures used to make the yogurt. Frozen yogurt will contain similarly reduced lactose levels. Greek yogurt is better for lactose intolerant people as more lactose is removed during processing.[47]

- Cheeses

Traditionally made hard cheeses, and soft-ripened cheeses may create less reaction than the equivalent amount of milk because of the processes involved. Fermentation and higher fat content contribute to lesser amounts of lactose. Traditionally made Emmental or Cheddar might contain 10% of the lactose found in whole milk. In addition, the ageing methods of traditional cheeses (sometimes over two years) reduce their lactose content to practically nothing.[48] Commercial cheeses, however, are often manufactured by processes that do not have the same lactose-reducing properties. Ageing of some cheeses is governed by regulations;[49] in other cases, no quantitative indication of degree of ageing and concomitant lactose reduction is given, and lactose content is not usually indicated on labels.

- Sour cream

If made in the traditional way, this may be tolerable, but most modern brands add milk solids.[50]

- Examples of lactose levels in foods

As industry standardization has not been established concerning lactose content analysis methods (nonhydrated form or the monohydrated form),[51] and considering that dairy content varies greatly according to labeling practices, geography, and manufacturing processes, lactose numbers may not be very reliable. The following table contains a guide to the typical lactose levels found in various foods.[52]

Dairy product Serving size Lactose content Percentage Milk, regular 250 ml/g 12 g 4.80% Milk, reduced fat 250 ml/g 13 g 5.20% Yogurt, plain, regular 200 g 9 g 4.50% Yogurt, plain, low-fat 200 g 12 g 6.00% Cheddar cheese 30 g 0.02 g 0.07% Cottage cheese 30 g 0.1 g 0.33% Butter 5 g 0.03 g 0.6% Ice cream 50 g 3 g 6.00%

Lactose in nondairy products

Lactose (also present when labels state lactoserum, whey, milk solids, modified milk ingredients, etc.) is a commercial food additive used for its texture, flavor, and adhesive qualities, and is found in foods such as processed meats[53] (sausages/hot dogs, sliced meats, pâtés), gravy stock powder, margarines,[54] sliced breads,[55][56] breakfast cereals, potato chips,[57] processed foods, medications, prepared meals, meal replacements (powders and bars), protein supplements (powders and bars), and even beers in the milk stout style. Some barbecue sauces and liquid cheeses used in fast-food restaurants may also contain lactose. Lactose is often used as the primary filler (main ingredient) in most Prescription and non-prescription solid pill form medications, though product labeling seldom mentions the presence of 'lactose' or 'milk', and neither do product monograms provided to Pharmacists, and most Pharmacists are unaware of the very wide scale yet common use of lactose in such medications until they contact the supplier or manufacturer for verification.

Kosher products labeled pareve or fleishig are free of milk. However, if a "D" (for "dairy") is present next to the circled "K", "U", or other hechsher, the food product likely contains milk solids,[53] although it may also simply indicate the product was produced on equipment shared with other products containing milk derivatives.

Alternative products

Plant-based "milks" and derivatives such as soy milk, rice milk, almond milk, coconut milk, hazelnut milk, oat milk, hemp milk, and peanut milk are inherently lactose-free. Low-lactose and lactose-free versions of foods are often available to replace dairy-based foods for those with lactose intolerance.

Lactase supplementation

When lactose avoidance is not possible, or on occasions when a person chooses to consume such items, then enzymatic lactase supplements may be used.[58][59]

Lactase enzymes similar to those produced in the small intestines of humans are produced industrially by fungi of the genus Aspergillus. The enzyme, β-galactosidase, is available in tablet form in a variety of doses, in many countries without a prescription. It functions well only in high-acid environments, such as that found in the human gut due to the addition of gastric juices from the stomach. Unfortunately, too much acid can denature it,[60] so it should not be taken on an empty stomach. Also, the enzyme is ineffective if it does not reach the small intestine by the time the problematic food does. Lactose-sensitive individuals can experiment with both timing and dosage to fit their particular needs.

While essentially the same process as normal intestinal lactose digestion, direct treatment of milk employs a different variety of industrially produced lactase. This enzyme, produced by yeast from the genus Kluyveromyces, takes much longer to act, must be thoroughly mixed throughout the product, and is destroyed by even mildly acidic environments. Its main use is in producing the lactose-free or lactose-reduced dairy products sold in supermarkets.

Rehabituation to dairy products

For healthy individuals with primary lactose intolerance, it may be possible in some cases for the bacteria in the large intestine to adapt to an altered diet and break down small quantities of lactose more effectively[61] by habitually consuming small amounts of dairy products several times a day over a period of time. This is not suitable for people who have an underlying or chronic illness which may have damaged the intestinal tract in a way which prevents the lactase enzyme from being expressed.

Environmental factors—more specifically, the consumption of lactose—may "play a more important role than genetic factors in the etio-pathogenesis of milk intolerance".[62]

Epidemiology

Overall, about 65% of people experience some form of lactase intolerance as they age past infancy, but there are significant differences between populations and regions, with rates as low as 5% among Northern Europeans and as high as more than 90% of adults in some communities of East Asia (see Figure).[63]

History

Lactase persistence is the phenotype associated with various autosomal dominant alleles prolonging the activity of lactase beyond infancy; conversely, lactase nonpersistence is the phenotype associated with primary lactase deficiency. Among mammals, lactase persistence is unique to humans — it evolved relatively recently (in the last 10,000 years) among some populations, and the majority of people worldwide remain lactase nonpersistent.[22] For this reason, lactase persistence is of some interest to the fields of anthropology, human genetics, and archeology, which typically use the genetically derived persistence/non-persistence terminology.[64]

Genetic analysis shows lactase persistence has developed several times in different places independently in an example of convergent evolution.[65]

Recognition of the extent and genetic basis of lactose intolerance is relatively recent. Though its symptoms were described as early as Hippocrates (460-370 BC),[66] until the 1960s, the prevailing assumption in the medical community was that tolerance was the norm and intolerance was either the result of milk allergy, an intestinal pathogen, or else was psychosomatic (it being recognised that some cultures did not practice dairying, and people from those cultures often reacted badly to consuming milk).[67][68] Two reasons were given for this perception. Firstly, many Western countries have a predominantly European heritage, so have low frequencies of lactose intolerance,[69] and have an extensive cultural history of dairying. Therefore, tolerance actually was the norm in most of the societies investigated by medical researchers at that point. Secondly, within even these societies, lactose intolerance tends to be under-reported: genetically lactase nonpersistent individuals can tolerate varying quantities of lactose before showing symptoms, and their symptoms differ in severity. Most are able to digest a small quantity of milk, for example in tea or coffee, without suffering any adverse effects.[9] Fermented dairy products, such as cheese, also contain dramatically less lactose than plain milk. Therefore, in societies where tolerance is the norm, many people who consume only small amounts of dairy or have only mild symptoms, may be unaware that they cannot digest lactose. Eventually, however, lactose intolerance was recognised in the United States to be correlated with race.[70][71][72] Subsequent research revealed intolerance was more common globally than lactase persistence,[73][74][75][76][77] and that the variation was genetic.[68][78]

Other animals

Most mammals normally cease to produce lactase and become lactose intolerant, after weaning.[79]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Lactose Intolerance". NIDDK. June 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Heyman MB (2006). "Lactose Intolerance in Infants, Children, and Adolescents". Pediatrics (Review). 118 (3): 1279–1286. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1721. PMID 16951027.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Deng Y, Misselwitz B, Dai N, Fox M (2015). "Lactose Intolerance in Adults: Biological Mechanism and Dietary Management". Nutrients (Review). 7 (9): 8020–35. doi:10.3390/nu7095380. PMC 4586575

. PMID 26393648.

. PMID 26393648. - 1 2 Berni Canani R, Pezzella V, Amoroso A, Cozzolino T, Di Scala C, Passariello A (Mar 10, 2016). "Diagnosing and Treating Intolerance to Carbohydrates in Children". Nutrients (Review). 8 (3): pii: E157. doi:10.3390/nu8030157. PMC 4808885

. PMID 26978392.

. PMID 26978392. - ↑ Suchy FJ, Brannon PM, Carpenter TO, Fernandez JR, Gilsanz V, Gould JB; et al. (2010). "NIH consensus development conference statement: Lactose intolerance and health.". NIH Consens State Sci Statements (Consensus Development Conference, NIH. Review). 27 (2): 1–27. PMID 20186234.

- ↑ "How many people are affected or at risk for lactose intolerance?". NICHD. 6 May 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ↑ Ingram, Catherine J. E.; Mulcare, Charlotte A.; Itan, Yuval; Thomas, Mark G.; Swallow, Dallas M. (2008-11-26). "Lactose digestion and the evolutionary genetics of lactase persistence". Human Genetics. 124 (6): 579–591. doi:10.1007/s00439-008-0593-6. ISSN 0340-6717.

- ↑ Bahna SL (2002). "Cow's milk allergy versus cow milk intolerance.". Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol (Review. Comparative Study.). 89 (6 Suppl 1): 56–60. PMID 12487206.

- 1 2 Savaiano DA, Levitt MD (1987). "Milk intolerance and microbe-containing dairy foods". J. Dairy Sci. 70 (2): 397–406. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(87)80023-1. PMID 3553256.

- ↑ Mądry, E.; Krasińska, B.; Woźniewicz, M. G.; Drzymała-Czyż, S. A.; Bobkowski, W.; Torlińska, T.; Walkowiak, J. A. (2011). "Tolerance of different dairy products in subjects with symptomatic lactose malabsorption due to adult type hypolactasia". Gastroenterology Review. 5: 310–315. doi:10.5114/pg.2011.25381.

- ↑ name="Sinden, A.A 1991 Emedicine|PED|1270|Lactose Intolerance" Guandalini S, Frye R, Rivera-Hernández D, Miller L, Borowitz S

- ↑ Lactose intolerance~overview at eMedicine

- ↑ Genetics of lactose intolerance

- ↑ Genetics Home Reference. "MCM6". Genetics Home Reference.

- 1 2 Benjamin Phelan (23 October 2012). "Evolution of lactose tolerance: Why do humans keep drinking milk?". Slate Magazine.

- ↑ "Lactose Intolerance". Johns Hopkins Health Library. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ↑ Gibbons, Ann (2 April 2015) How Europeans evolved white skin Science, Retrieved 13 April 2015

- ↑ Beja-Pereira A, et al. (2003). "Gene-culture coevolution between cattle milk protein genes and human lactase genes". Nat Genet. 35: 311–313. doi:10.1038/ng1263.

- ↑ Ingram CJ, Mulcare CA, Itan Y, Thomas MG, Swallow DM (Jan 2009). "Lactose digestion and the evolutionary genetics of lactase persistence". Hum Genet. 124 (6): 579–91. doi:10.1007/s00439-008-0593-6.

- ↑ Tishkoff et al. 2006.

- ↑ Enattah NS, Sahi T, Savilahti E, Terwilliger JD, Peltonen L, Järvelä I (2002). "Identification of a variant associated with adult-type hypolactasia". Nat. Genet. 30 (2): 233–7. doi:10.1038/ng826. PMID 11788828.

- 1 2 Swallow DM (2003). "Genetics of lactase persistence and lactose intolerance". Annual Review of Genetics. 37: 197–219. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143820. PMID 14616060.

- ↑ "Lactose intolerance".

- ↑ Secundary lactase deficiency causes

- ↑ Swagerty DL, Walling AD, Klein RM (2002). "Lactose intolerance". Am Fam Physician. 65 (9): 1845–50. PMID 12018807.

- ↑ Lawson, Margaret; Bentley, Donald; Lifschitz, Carlos (2002). Pediatric gastroenterology and clinical nutrition. London: Remedica. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-901346-43-5.

- ↑ Pediatric Lactose Intolerance at eMedicine

- ↑ Swagerty DL, Walling AD, Klein RM (2002). "Lactose intolerance". Am Fam Physician (Review). 65 (9): 1845–50. PMID 12018807.

- ↑ R. Bowen (December 28, 2006). "Lactose Intolerance (Lactase Non-Persistence)". Pathophysiology of the Digestive System. Colorado State University.

- ↑ Olivier CE, Lorena SL, Pavan CR, dos Santos RA, dos Santos Lima RP, Pinto DG, da Silva MD, de Lima Zollner R (2012). "Is it just lactose intolerance?". Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 33 (5): 432–6. doi:10.2500/aap.2012.33.3584. PMID 23026186.

- ↑ "Lactose Intolerance Tests and Results". WebMD.

- ↑ "Lactose tolerance tests". 3 May 2011.

- ↑ National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (March 2006). "Lactose Intolerance — How is lactose intolerance diagnosed?". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

- ↑ "Stool Acidity Test". Jay W. Marks, M.D. Retrieved 2011-05-20.

- 1 2 3 Hargrove, James L.; Berdanier, Carolyn D. (1993). Nutrition and gene expression. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-6961-4.

- ↑ Kuokkanen M, Myllyniemi M, Vauhkonen M, Helske T, Kääriäinen I, Karesvuori S, Linnala A, Härkönen M, Järvelä I, Sipponen P (2006). "A biopsy-based quick test in the diagnosis of duodenal hypolactasia in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy". Endoscopy. 38 (7): 708–12. doi:10.1055/s-2006-925354. PMID 16761211.

- ↑ Deng Y, Misselwitz B, Dai N, Fox M (2015). "Lactose Intolerance in Adults: Biological Mechanism and Dietary Management". Nutrients (Review). 7 (9): 8020–35. doi:10.3390/nu7095380. PMC 4586575

. PMID 26393648.

. PMID 26393648. - ↑ Enattah NS, Sahi T, Savilahti E, Terwilliger JD, Peltonen L, Järvelä I (2002). "Identification of a variant associated with adult-type hypolactasia". Nature Genetics. 30 (2): 233–7. doi:10.1038/ng826. PMID 11788828.

- ↑ Vandenplas Y (2015). "Lactose intolerance.". Asia Pac J Clin Nutr (Review). 24 Suppl 1: S9–13. doi:10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.s1.02. PMID 26715083.

- ↑ Levy J, Bernstein L, Silber N (Dec 2014). "Celiac disease: an immune dysregulation syndrome". Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care (Review). 44 (11): 324–7. doi:10.1016/j.cppeds.2014.10.002. PMID 25499458.

Initially, reduced levels of lactase and sucrase activities might necessitate further dietary restrictions until the villi have healed and those sugars are better tolerated.

- ↑ Lactose Intolerance at eMedicine Roy, Barakat, Nwakakwa, Shojamanesh, Khurana, July 5, 2006

- ↑ Szilagyi A (2015). "Adaptation to Lactose in Lactase Non Persistent People: Effects on Intolerance and the Relationship between Dairy Food Consumption and Evalution [sic] of Diseases". Nutrients (Review). 7 (8): 6751–79. doi:10.3390/nu7085309. PMC 4555148

. PMID 26287234.

. PMID 26287234. - ↑ http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/doc/1763.pdf

- ↑ Gary Pfalzbot (25 December 2003). "Composition of Human, Cow, and Goat Milks - Goat Milk - GOATWORLD.COM".

- ↑ Peeva (2001). "Composition of buffalo milk. Sources of specific effects on the separate components". Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 7: 329–35.

- ↑ C:\JAG2\Jiang.vp

- ↑ "Can a Lactose Intolerant Eat Some Yogurt & Aged Cheese?".

- ↑ "Dairy Good: Home".

- ↑ "PDO - Our Provenance, speciality fine cheese : West Country Farmhouse Cheesemakers : Handmade Westcountry Farmhouse Cheeses".

- ↑ Reger, Combs, Coulter and Koch (February 1, 1951). "A Comparison of Dry Sweet Cream Buttermilk and Non-Fat Dry Milk Solids in Breadmaking". Journal of Dairy Science. 34 (2): 136–44. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(51)91682-7.

- ↑ "Goat Dairy Foods".

- ↑ "Diet for Lactose Intolerance".

- 1 2 "General guidelines for milk allergy". Oregon Health & Science University.

- ↑ "Margarine Regulations".

- ↑ "Enriched White Bread in Canada". The Canadian Celiac Association.

- ↑ Riggs, Lloyd K; Beaty, Annabel; Johnson, Arnold H (December 1946). "Influence of Nonfat Dry Milk Solids on the Nutritive Value of Bread". Journal of Dairy Science. 29 (12): 821–9. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(46)92546-5.

- ↑ "Bartek, food additive company" (PDF).

- ↑ Montalto M, Curigliano V, Santoro L, Vastola M, Cammarota G, Manna R, Gasbarrini A, Gasbarrini G (2006). "Management and treatment of lactose malabsorption". World J. Gastroenterol. 12 (2): 187–91. PMID 16482616.

- ↑ He M, Yang Y, Bian L, Cui H (1999). "[Effect of exogenous lactase on the absorption of lactose and its intolerance symptoms]". Wei Sheng Yan Jiu (in Chinese). 28 (5): 309–11. PMID 12712706.

- ↑ O'Connell S, Walsh G (2006). "Physicochemical characteristics of commercial lactases relevant to their application in the alleviation of lactose intolerance". Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 134 (2): 179–91. doi:10.1385/ABAB:134:2:179. PMID 16943638.

- ↑ Lactose intolerant? Drink more milk Steve Tally

- ↑ Yoshida Y, Sasaki G, Goto S, Yanagiya S, Takashina K (1975). "Studies on the etiology of milk intolerance in Japanese adults". Gastroenterol. Jpn. 10 (1): 29–34. PMID 1234085.

- ↑ "Lactose intolerance". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ Curry, Andrew (31 July 2013). "Archaeology: The milk revolution". Nature.

- ↑ Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Ranciaro A, Voight BF, Babbitt CC, Silverman JS, Powell K, Mortensen HM, Hirbo JB, Osman M, Ibrahim M, Omar SA, Lema G, Nyambo TB, Ghori J, Bumpstead S, Pritchard JK, Wray GA, Deloukas P (10 December 2006). "Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe". Nature Genetics. 39 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1038/ng1946. PMC 2672153

. PMID 17159977. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

. PMID 17159977. Retrieved 18 April 2013. - ↑ Wilson J (December 2005). "Milk Intolerance: Lactose Intolerance and Cow's Milk Protein Allergy". Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews. 5 (4): 203–7. doi:10.1053/j.nainr.2005.08.004.

- ↑ Auricchio S, Rubino A, Landolt M, Semenza G, Prader A (1963). "Isolated intestinal lactase deficiency in the adult". Lancet. 2 (7303): 324–6. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(63)92991-x. PMID 14044269.

- 1 2 Simoons FJ (December 1969). "Primary adult lactose intolerance and the milking habit: a problem in biological and cultural interrelations. I. Review of the medical research". Am J Dig Dis. 14 (12): 819–36. doi:10.1007/bf02233204. PMID 4902756.

- ↑ Itan Y, Jones BL, Ingram CJ, Swallow DM, Thomas MG (2010). "A worldwide correlation of lactase persistence phenotype and genotypes". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10: 36. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-36. PMC 2834688

. PMID 20144208.

. PMID 20144208. - ↑ Bayless TM, Rosensweig NS (1966). "A racial difference in incidence of lactase deficiency. A survey of milk intolerance and lactase deficiency in healthy adult males". JAMA. 197 (12): 968–72. doi:10.1001/jama.1966.03110120074017. PMID 5953213.

- ↑ Welsh JD, Rohrer V, Knudsen KB, Paustian FF (1967). "Isolated Lactase Deficiency: Correlation of Laboratory Studies and Clinical Data.". Archives of Internal Medlit. 120 (3): 261–269. doi:10.1001/archinte.1967.00300030003003.

- ↑ Huang SS, Bayless TM (1968). "Milk and lactose intolerance in healthy Orientals". Science. 160 (3823): 83–4. doi:10.1126/science.160.3823.83-a. PMID 5694356.

- ↑ Cook GC, Kajubi SK (1966). "Tribal incidence of lactase deficiency in Uganda". Lancet. 1 (7440): 725–9. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(66)90888-9. PMID 4159716.

- ↑ Jersky J, Kinsley RH (1967). "Lactase Deficiency in the South African Bantu". South African Medical Journal. 41 (Dec): 1194–1196.

- ↑ Bolin TD, Crane GG, Davis AE (1968). "Lactose intolerance in various ethnic groups in South-East Asia". Australas Ann Med. 17 (4): 300–6. PMID 5701921.

- ↑ Flatz G, Saengudom C, Sanguanbhokhai T (1969). "Lactose intolerance in Thailand". Nature. 221 (5182): 758–9. doi:10.1038/221758b0. PMID 5818369.

- ↑ Elliott RB, Maxwell GM, Vawser N (1967). "Lactose maldigestion in Australian Aboriginal children". Med. J. Aust. 1 (2): 46–9. PMID 6016903.

- ↑ Flatz G, Rotthauwe HW (1971). "Evidence against nutritional adaption of tolerance to lactose". Humangenetik. 13 (2): 118–25. doi:10.1007/bf00295793. PMID 5114667.

- ↑ Swallow DM (2003). "Genetics Oflactasepersistence Andlactoseintolerance". Annual Review of Genetics. 37: 197–219. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143820. PMID 14616060.