Le Père Duchesne

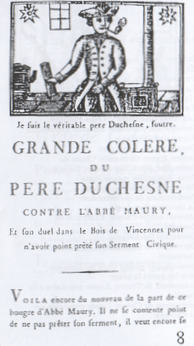

Cover of issue no. 25 of Hébert's Le Père Duchesne | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Editor | Jacques Hébert |

| Founded | 1790 |

| Political alignment |

Hebertism, Political radicalism |

| Language | French |

| Ceased publication | 24 March 1794 |

| Headquarters | Paris, French Republic |

| Circulation | unknown |

Le Père Duchesne (French pronunciation: [lə pɛʁ dyʃɛn], Old Man Duchesne or Father Duchesne) was an extreme radical newspaper during the French Revolution, edited by Jacques Hébert, who published 385 issues from September 1790 until eleven days before his death by guillotine, which took place on March 24, 1794. The title was used again hundreds of times afterwards, mainly during revolutionary periods, for publications with no direct connection to the original: for example, during the July Revolution of 1830, the Revolution of 1848, and during the Paris Commune (1871).

History

To be denounced as an enemy of the Republic by Le père Duchesne often led to the guillotine. The journal never hesitated to ask, in its own words, that the "carriage with thirty-six doors" lead such and such a "toad of the Marais", "to sneeze in the bag", "to ask the time from the fanlight", "to try on Capet's necktie".

Born in the fairs of the 18th century, Père Duchesne was a character representing the man of the people, always moved to denounce abuses and injustices. This imaginary character is found in a text entitled le plat de Carnaval ("the Carnival dish"), as well as an anonymous minor work in February 1789 called "Journey of Père Duchesne to Versailles" or "Père Duchesne's Anger at the Prospect of Abuses" in the same year.

In 1789, several pamphlets had been published under this name. In 1790, an employee of the post office by the name of Antoine Lemaire and Abbé Jean-Charles Jumel had been attacked in newspapers resorting to the fictional pseudonym Père Duchesne, but the Père Duchesne of Hébert, the one whom the street-criers sold by yelling, "Père Duchesne's damn angry today!" was distinguished by the violence which characterized his style.

From 1790 to 1791, Père Duchesne represented the constitutional faction, and eulogized King Louis XVI and the Marquis de La Fayette, blaming, on the one hand, Marie Antoinette and, on the other, Jean-Paul Marat, and saving his fire for Jean-Sifrein Maury, the great defender of papal authority against the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. In 1792, the government printed certain issues of Père Duchesne at the expense of the Republic, in order to distribute them to the army to rouse soldiers from a torpor considered dangerous to public safety.

Originally, the publication, begun by the printer Tremblay, was made up of 8 pages in unnumbered octavo format, and appeared three times a week. The first page was headed with a scene representing Père Duchesne with a pipe in one hand and a cone of tobacco in the other, accompanied by the caption: "I am the true fucking Père Duchesne!" with Maltese crosses on each side. The numbering of the newspaper began with the first issue in January 1791. Beginning with issue number 13, it copied a scene from another Père Duchesne which was published in the Rue Vieux-Colombier, which represented a man with a moustache, saber at his side and a hatchet raised to a priest to whom he utters a menacing memento mori: "Remember your mortality!". Beginning with issue 138, Hébert left his editor Tremblay, who would himself publish several counterfeits.

As soon as Hébert was guillotined, these counterfeit Père Duchesnes had a field day, producing parodies such as The great anger of Père Duchesne seeing his head fall from the national window. Others, such as Saint-Venant, would try, with Moustache without fear, to write new parodies in the spirit of the time and in the same lewd gutter style that characterized Hébert. Lebon published one of them in 1797, and Damane published 32 issues under the name Père Duchesne in Lyon.

The title was reprised numerous times in the 19th century.

Notes

- ^ [tr.:] A reference to the Revolutionary tumbrels. Originally tumbrels (or tumbrils) were farmers' carts that were used for dumping – particularly manure. This was the name given to the carts that carried prisoners to their death at the guillotine.

- ^ [tr.:] Marais means marsh (where toads could be found.) "During the French Revolution, "le Marais" (also called "La Plaine") was the name given to the most moderate, but most numerous, group of deputies in the National Convention. This alluded [to the fact that they sat] in the middle of the assembly, as well as [to] their indecision. ["Le marais" was] a "marsh" where law projects got bogged down." (It is also a very old district of Paris.)

- ^ [tr.:] A gruesome reference to the fact that the heads of the guillotined were thrown into a sack.

- ^ [tr.:] Another lurid reference to the fact that the executioner would pick up the head of a guillotined person and hold it up high for the crowd to see. This would put the executed's face at the same height as the fanlight windows on top of entry doors, conjuring up the grisly idea that the head would then be able to ask the high window what time it was.

- ^ [tr.:] Capet was the family name of the Kings of France (descendants of the medieval Hugh Capet) and was frequently used in the Revolutionary period as a derogatory name for the King and Queen, to bring them down to the common level. Capet's necktie is clearly a reference to the guillotine, where both King and Queen ended their lives.

- ^ [tr.:] A law passed on July 12, 1790 by the National Constituent Assembly, profoundly reorganizing the Church of France and making parish priests "ecclesiastical public officials".

- ^ [tr.:] Lyon was called Commune-Affranchie – or "Liberated City" – during the Revolution, and the pamphlets were published under that name.