List of countries and islands by first human settlement

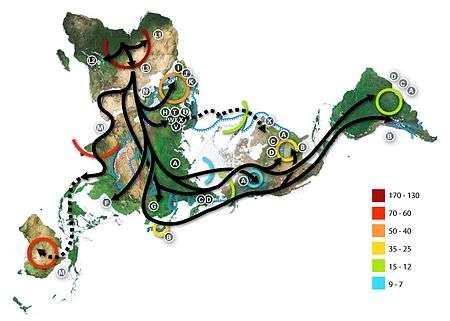

Though fossils of hominids have been found dating back millions of years, the earliest known Homo sapiens remains are considered to be a group of bones found at the Omo Kibish Formation, near the Ethiopian Kibish Mountains. Though believed to be 130,000 years old at their discovery in 1967, recent studies have dated them as far back as 195,000 years old.[1] From this area, humans spread out to cover all continents except Antarctica by 14,000 BP. According to a recent theory, humans may have crossed over into the Arabian Peninsula as early as 125,000 years ago.[2] From the Middle East, migration continued into India around 70,000 years ago, and Southeast Asia shortly after. Settlers could have crossed over to Australia and New Guinea – that were united as one continent at the time due to lower sea levels – as early as 55,000 years ago.[3] Migration into Europe took somewhat longer to occur; the first definite evidence of human settlement on this continent has been discovered in southern Italy, and dates back 43-45,000 years.[4] Settlement of Europe may have occurred as early as 45,000 years ago though, according to genetic research.[5] The Americas were populated by humans at least as early as 14,800 years ago,[6] though there is great uncertainty about the exact time and manner in which the Americas were populated.[7] More remote parts of the world, like Iceland, New Zealand and Madagascar were not populated until the historic era.[8]

The following table shows any geographical region at some point defined as a country – not necessarily a modern-day sovereign state – or any geographically distinct area such as an island, with the date of the first known or hypothesised human settlement. Dates are, unless specifically stated, approximate. Settlements are not necessarily continuous; settled areas in some cases become depopulated due to environmental conditions, such as glacial periods or the Toba volcanic eruption.[9] Where applicable, information is also given on the exact location where the settlement was discovered, and further information about the discovery. Some dates are based on genetic research (mitochondrial, or matrilinear DNA), and not on archaeological finds.

The list

| Country | Date | Place | Notes | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethiopia | 195,000 BP | Omo Kibish Formation | The Omo remains found in 1967 near the Ethiopian Kibish Mountains, have been dated as ca. 195,000 years old, making them the earliest human remains ever found. They are older than the remains found at Herto Bouri, Ethiopia (155–160,000 BP). | [1] |

| Morocco | 90,000–190,000 BP | Jebel Irhoud | Anatomically modern human remains of uncertain date | [10] |

| Sudan | 140,000–160,000 BP | Singa | Anatomically modern human discovered 1924 with rare temporal bone pathology | [11][12] |

| United Arab Emirates | 125,000 BP | Jebel Faya | Stone tools made by anatomically modern humans | [13] |

| South Africa | 125,000 BP | Klasies River Caves | Remains found in the Klasies River Caves in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa show signs of human hunting. There is some debate as to whether these remains represent anatomically modern humans. | [14][15] |

| Israel | 100,000 BP | Skhul/Qafzeh | Discovered in 1929-1935; remains exhibit a mix of archaic and modern traits and may represent an early migration from Africa that died out by 80,000 years ago. | [16] |

| Oman | 75,000–125,000 BP | Aybut | Tools found in the Dhofar Governorate correspond with African objects from the so-called 'Nubian Complex', dating from 75-125,000 years ago. According to archaeologist Jeffrey I. Rose, human settlements spread east from Africa across the Arabian Peninsula. | [2] |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 90,000 BP | Katanda, Upper Semliki River | Semliki harpoon heads carved from bone. | [17] |

| India | 70,000 BP | Jwalapuram, Andhra Pradesh | Recent finds of stone tools in Jwalapuram before and after the Toba supereruption, may have been made by modern humans, but this is disputed. | [3][18] |

| Philippines | 67,000 BP | Callao Cave | Archaeologists, Dr. Armand Mijares with Dr. Phil Piper found bones in a cave near Peñablanca, Cagayan in 2010 have been dated as ca. 67,000 years old. It's the earliest human fossil ever found in Asia-Pacific | [19] |

| Libya | 50,000–180,000 BP | Haua Fteah | Fragments of 2 mandibles discovered in 1953 | [20] |

| Egypt | 50,000–80,000 BP | Taramasa Hill | Skeleton of 8- to 10-year-old child discovered in 1994 | [21] |

| Taiwan | 50,000 BP | Chihshan Rock Site | Chipped stone tool similar to those of the Changpin culture on the east coast. | [22] |

| Brazil | 41,000–56,000 BP | Pedra Furada | Charcoal from the oldest layers yielded dates of 41,000-56,000 BP. | [23] |

| Australia | 48,000 BP | Devil's Lair | The oldest human skeletal remains are the 40,000-year-old Lake Mungo remains in New South Wales, but human ornaments discovered at Devil's Lair in Western Australia have been dated to 48,000 BP. Ochre fragments at Malakunanja II in Northern Territory are dated to ca. 45,000 BP. | [24][25][26] |

| Japan | 47,000 BP | Lake Nojiri | Genetic research indicates arrival of humans in Japan by 37,000 BP. Archeological remains at the Tategahana Paleolithic Site at Lake Nojiri have been dated as early as 47,000 BP. | [3][27] |

| Laos | 46,000 BP | Annamite Range | In 2009 an ancient skull was recovered from a cave in the Annamite Mountains in northern Laos which is at least 46,000 years old, making it the oldest modern human fossil found to date in Southeast Asia | [28] |

| Borneo | 46,000 BP | (see Malaysia) | ||

| Greece | 45,000 BP | Mount Parnassus | Geneticist Bryan Sykes identifies 'Ursula' as the first of The Seven Daughters of Eve, and the carrier of the mitochondrial haplogroup U. This hypothetical woman moved between the mountain caves and the coast of Greece, and based on genetic research represent the first human settlement of Europe. | [5] |

| Italy | 43,000–45,000 BP | Grotta del Cavallo, Apulia | Two baby teeth discovered in Apulia in 1964 are the earliest modern human remains yet found in Europe. | [4] |

| Indonesia | 45,000 BP | Early humans travelled by sea and spread from mainland Asia eastward to New Guinea and Australia | [29] | |

| United Kingdom | 41,500–44,200 BP | Kents Cavern | Human jaw fragment found in Torquay, Devon in 1927 | [30] |

| Germany | 42,000–43,000 BP | Geißenklösterle, Baden-Württemberg | Three Paleolithic flutes belonging to the early Aurignacian, which is associated with the assumed earliest presence of Homo sapiens in Europe (Cro-Magnon). It is the oldest example of prehistoric music. | [31] |

| Lithuania | 41,000–43,000 BP | Šnaukštai near Gargždai | A hammer made from reindeer horn similar to those used by the Bromme culture was found in 2016. The discovery pushed back the earliest evidence of human presence in Lithuania by 30,000 years, i.e. to before the last glacial period. | [32] |

| East Timor | 42,000 BP | Jerimalai cave | Fish bones | [33] |

| China | 39,000–42,000 BP | Tianyuan Cave | Bones found in a cave near Beijing in 1958 have been radiocarbon dated at between 39–42,000 years old. | [34] |

| Tasmania | 41,000 BP | Jordan River Levee | Optically stimulated luminescence results from the site suggest a date ca. 41,000 BP. Rising sea level left Tasmania isolated after 8000 BP. | [35] |

| Hong Kong | 39,000 BP | Wong Tei Tung | Optically stimulated luminescence results from the site suggest a date ca. 39,000 BP. | [36] |

| Malaysia | 34,000–46,000 BP | Niah Cave | A human skull in Sarawak, Borneo (Archaeologists have claimed a much earlier date for stone tools found in the Mansuli valley, near Lahad Datu in Sabah, but precise dating analysis has not yet been published.) | [37][38] |

| New Guinea | 40,000 BP | Indonesian Side of New Guinea | Archaeological evidence shows that 40,000 years ago, some of the first farmers came to New Guinea from the South-East Asian Peninsula. | [3] |

| Romania | 37,800–42,000 BP | Peștera cu Oase | Bones dated as 38–42,000 years old are among the oldest human remains found in Europe. | [39][40] |

| Sri Lanka | 34,000 BP | Fa Hien Cave | The earliest remains of anatomically modern man, based on radiocarbon dating of charcoal, have been found in the Fa Hien Cave in western Sri Lanka. | [41] |

| Canada | 25,000–40,000 BP | Bluefish Caves | Human-worked mammoth bone flakes found at Bluefish Caves, Yukon, are much older than the stone tools and animal remains at Haida Gwaii in British Columbia (10-12,000 BP) and indicate the earliest known human settlement in North America. | [42][43] |

| Okinawa | 32,000 BP | Yamashita-cho cave, Naha city | Bone artifacts and an ash seam dated to 32,000±1000 BP. | [44] |

| France | 32,000 BP | Chauvet Cave | The cave paintings in the Chauvet Cave in southern France have been called the earliest known cave art, though the dating is uncertain. | [45] |

| Czech Republic | 31,000 BP | Mladeč | Oldest human bones that clearly represent a human settlement in Europe. | [46] |

| Poland | 30,000 BP | Obłazowa Cave | A boomerang made from mammoth tusk | |

| Buka Island, New Guinea | 28,000 BP | Kilu cave | Flaked stone, bone, and shell artifacts | [47] |

| Russia | 28,000-30,000 BP | Sungir | Burial site | |

| Portugal | 24,500 BP | Abrigo do Lagar Velho | Possible Neanderthal/Cro-Magnon hybrid, the Lapedo child | [48] |

| Sicily | 20,000 BP | San Teodoro cave | Human cranium dated by gamma-ray spectrometry | [49] |

| United States | 16,000 BP | Meadowcroft Rockshelter | Stone, bone, and wood artifacts and animal and plant remains found in Washington County, Pennsylvania. (Earlier claims have been made, but not corroborated, for sites such as Topper, South Carolina.)[50] | [51] |

| Chile | 14,800 BP | Monte Verde | Carbon dating of remains from this site represent the oldest known settlement in South America. | [52] |

| Peru | 14,000 BP | Pikimachay | Stone and bone artifacts found in a cave of the Ayacucho complex | [53] |

| Santa Rosa Island | 13,000 BP | Arlington Springs site | Arlington Springs Man discovered in 1959. The four northern Channel Islands of California were once conjoined into one island, Santa Rosae | |

| Cyprus | 12,500 BP | Aetokremnos | Burned bones of megafauna | [54] |

| Colombia | 12,400 BP | El Abra | Stone, bone and charcoal artifacts | |

| Norway | 9,200 BC | Aukra | The oldest remnants of the so-called Fosna culture were found in Aukra in Møre og Romsdal, and date from this period. | [55] |

| Argentina | 9,000 BC | Piedra Museo | Spear heads and human fossils | [56] |

| Bioko | 8,000 BC | Early Bantu migration | [57] | |

| Ireland | 7,700 BC | Mount Sandel | Carbon dating of hazel nut shells reveals this place to have been inhabited for 9,700 years. | [58][59] |

| Estonia | 7,600 BC | Pulli | The Pulli settlement on the bank of the Pärnu River briefly pre-dates that at Kunda, which gave its name to the Kunda culture. | [60] |

| Cambodia | 7,000 BC | Laang Spean | Laang Spean cave in the Stung Sangker River valley, Battambang Province | [61] |

| Zhokhov Island | 6,300 BC | Hunting tools and animal remains in the High Arctic | [62][63] | |

| Tuvalu | 6,000 BC | Caves of Nanumanga | Evidence of fire in a submerged cave last accessible 8000 BP | [64] |

| Malta | 5,200 BC | Għar Dalam | Settlers from Sicily brought agriculture and impressed ware pottery. | [65] |

| Trinidad | 5,000 BC | Banwari Trace | Stone and bone artifacts mark the oldest archaeological site in the Caribbean. | [66] |

| Puerto Rico | 4,000 BC | Angostura site | Carbon dating of burial site | [67] |

| Mariana Islands | 3,000 BC | Carbon dating of charcoal | [68] | |

| Greenland | 2,000 BC | Saqqaq | Saqqaq culture was the first of several waves of settlement from northern Canada and from Scandinavia. | [69] |

| Baffin Island, Canada | 2,000 BC | Pond Inlet | In 1969, Pre-Dorset remains were discovered, with seal bones radiocarbon dated to 2035 BC | [70] |

| Wrangel Island | 1,400 BC | Chertov Ovrag | Sea-mammal hunting tools | [71] |

| Tonga | 1,180 BC | Pea village on Tongatapu | Radiocarbon dating of a shell found at the site dates the occupation at 3180±100 BP. | [72] |

| Fiji | 1,095 BC | Bourewa | Radiocarbon dating of a shell midden at Bourewa on Viti Levu Island shows earliest inhabitation at 1220-970 BC. | [73] |

| Canary Islands | 1,000 BC | Genetic studies show relation to Moroccan Berbers, but precise date uncertain. | [74] | |

| Vanuatu | 1,000 BC | Teouma etc. | Lapita pottery found at Teouma cemetery on Efate and on several other islands. | [75] |

| Samoa | 1,000 BC | Mulifanua | Lapita site found at Mulifanua Ferry Berth Site by New Zealand scientists in the 1970s. | [76] |

| Hawaii | 290 AD | Ka Lae | Early settlement from the Marquesas Islands | [77] |

| Madagascar | 500 AD | The population of Madagascar seems to have derived in equal measures from Borneo and East Africa. | [78] | |

| Comoros | 550 AD | |||

| Faroe Islands | 600 AD | Agricultural remains from three locations were analysed and dated to as early as the sixth century A.D. | [79] | |

| Bahamas | 850 AD | Three Dog Site (SS21), San Salvador Island | Excavated midden includes quartz and Ostionoid ceramic artifacts, wood and seed remains, etc., dated to 800-900 AD. | [80] |

| Iceland | 874 AD | Reykjavík | Ingólfr Arnarson, the first known Norse settler who came from mainland Norway, built his homestead in Reykjavík this year, though Norse or Hiberno-Scottish monks might have arrived up to two hundred years earlier. | [8] |

| Huahine, French Polynesia | 960 AD | Fa'ahia | Bird bones dated to 1140±90 BP | [81] |

| Raiatea, French Polynesia | 1000 AD | Taputapuatea marae | Stone religious structures established by 1000 AD. | |

| Pitcairn Island | 1050 AD | Settled by Polynesians in the 11th century, later abandoned. Resettled by British and Polynesians 1790. | ||

| Easter Island | 500-1200 AD | Anakena | Settled by voyagers from the Marquesas Islands, possibly as early as 300 AD. | [82] |

| New Zealand | 1250–1300 AD | Wairau Bar | Though some researchers suggest settlements as early as 50–150 AD, that later became extinct, it is generally accepted that the islands were permanently settled by Eastern Polynesians (the ancestors of the Māori) who arrived about 1250–1300 AD. | [83][84] |

| Norfolk Island | 1300 AD | Emily Bay | Settled by Polynesians, later abandoned. Resettled by British 1788. | [85][86] |

| Auckland Islands | 1300 AD | Sandy Bay, Enderby Island | Settled by Polynesians, later abandoned. Resettled from the Chatham Islands in 1842, later abandoned. | [86] |

| Kermadec Islands | 1400 AD | Settled by Polynesians, later abandoned. Resettled by Europeans in 1810, later abandoned. | ||

| Madeira | 1420 AD | Settlers from Portugal. | ||

| Azores | 1439 AD | Santa Maria Island | Settlers from Portugal led by Gonçalo Velho Cabral. | [87] |

| Cape Verde | 1462 AD | Cidade Velha | Settlers from Portugal. | |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | 1485 AD | São Tomé | Portuguese settlement in 1485 failed but was followed in 1493 by a successful settlement led by Álvaro Caminha. | [88] |

| Saint Helena | 1516 AD | Settled by Fernão Lopes (soldier). Later populated by escaped slaves from Mozambique and Java, then by English in 1659. | [89] | |

| Annobón | 1543 AD | Alvaro da Cunha requested Portuguese royal charter in 1543 and by 1559 had settled Africans slaves there. | [90] | |

| Chatham Islands | 1550 AD | Moriori settlers from New Zealand. This was the last wave of Polynesian migrations. | [91] | |

| Bermuda | 1609 AD | Settled by English survivors of the Sea Venture shipwreck, led by George Somers. | ||

| Svalbard | 1619 AD | Smeerenburg | Settled by Dutch and Danish whalers 1619-1657. Longyearbyen founded 1906 and continuously inhabited except for World War II. | [92] |

| Mauritius | 1638 AD | Vieux Grand Port | First settled by Dutch under Cornelius Gooyer. | [93] |

| Réunion | 1642 AD | Settled 1642 by a dozen deported French mutineers from Madagascar, who were returned to France several years later. In 1665 the French East India Company started a permanent settlement. | ||

| Rodrigues | 1691 AD | Settled 1691 by a small group of French Huguenots led by François Leguat; abandoned 1693. The French settled slaves there in the 18th century. | [94] | |

| Falkland Islands | 1764 AD | Puerto Soledad | Settled by French during the expedition of Louis Antoine de Bougainville. | [95] |

| Seychelles | 1770 AD | Ste. Anne Island | Although visited earlier by Maldivians, Malays and Arabs, the first known settlement was a spice plantation established by the French, first on Ste. Anne Island, then moved to Mahé. | [96] |

| Tristan da Cunha | 1810 AD | First settled by Jonathan Lambert and two other men. Continuously inhabited since then except 1961-1963 evacuation due to volcano. | [97] | |

| Ascension Island | 1815 AD | Settled as a British military garrison. | ||

| Bonin Islands | 1830 AD | Port Lloyd, Chichi-jima | Some evidence of early settlement from the Marianas, but the islands were abandoned except for occasional shipwrecks until a group of Europeans, Polynesians, and Micronesians settled Chichi-jima in 1830. | [98] |

| Lord Howe Island | 1834 AD | Blinky Beach | Whaling supply station. | [86] |

| Île Saint-Paul | 1843 AD | Although now uninhabited, there have been attempts at settlement. In June, 1843, a French garrison was established under the command of Polish-born Captain Adam Mierolawski, but it was soon abandoned. In 1928, a spiny lobster cannery was established, with the last two or three settlers rescued in 1934. | [99][100] | |

| Île Amsterdam | 1871 AD | Camp Heurtin | Following various shipwrecks and visits by sealers and scientists in the 18th and 19th century, a short-lived settlement was made in 1871 by Heurtin, a French resident of Réunion Island. A French scientific base has been maintained since 1949. | [101] |

| South Orkney Islands | 1903 AD | Orcadas Base | Visited by sealers and whalers in the 19th century. Scientific base founded by Scottish National Antarctic Expedition and sold to Argentina in 1904. | |

| South Georgia | 1904 AD | Grytviken | Visited by sealers in the 19th century. Carl Anton Larsen founded a permanent whaling station in 1904. | |

| Jan Mayen | 1921 AD | Eggøya | Visited by whalers in the 17th century, with some overwinter sojourns in 1633, 1882, and 1907. Weather station at Eggøya established 1921, followed by other weather and military stations. The current station, Olonkinbyen, has been continuously inhabited since 1958. | [102] |

| Kerguelen Islands | 1927 AD | Port-Couvreux | After occasional sojourns and shipwrecks in the 19th century, three families settled in a sheep-farming colony but were evacuated in 1934. Scientific station at Port-aux-Français has been continuously inhabited since 1950. | |

| South Shetland Islands | 1947 AD | Captain Arturo Prat Base | Visited by sealers and explorers in the 19th century. Chilean naval base staffed continuously 1947-2004. | |

| Prince Edward Islands | 1947 AD | Transvaal Cove | Visited by sealers and shipwrecks in the 19th century. South Africa occupied the islands in 1947 and established a meteorological station. | [103] |

| Antarctica | 1948 AD | Base General Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme | First permanent base in mainland Antarctica, operated by the Chilean Army. | |

| Macquarie Island | 1948 AD | Macquarie Island Station | Occasional sojourns and shipwrecks in the 19th century, continuously inhabited since 1948. | |

| Crozet Islands | 1963 AD | Alfred Faure | Occasional shipwrecks and visiting sealers and whalers in the 19th century, continuously inhabited since 1963. |

See also

- Early human migrations

- Historical migration

- Human evolution

- List of human evolution fossils

- Timeline of human evolution

References

- 1 2 "The Oldest Homo Sapiens: Fossils Push Human Emergence Back To 195,000 Years Ago". Science Daily. 28 February 2005. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- 1 2 "125,000 years ago first human settlement began in Sultanate". Oman Daily Observer. 7 April 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Stanyon, Roscoe; Marco Sazzini; Donata Luiselli (2009). "Timing the first human migration into eastern Asia". Journal of Biology. 8 (2): 18. doi:10.1186/jbiol115. ISSN 1475-4924. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- 1 2 Benazzi, Stefano; et al. (24 Nov 2011). "Early dispersal of modern humans in Europe and implications for Neanderthal behaviour". Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 479 (7374): 525–528. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..525B. doi:10.1038/nature10617. PMID 22048311. Retrieved 2012-04-19. Lay summary – BBC News (2011-11-02).

- 1 2 Sykes, Bryan (2002). The Seven Daughters of Eve. London: Corgi. p. 202. ISBN 0-552-15218-8.

- ↑ Wilford, John Noble (4 April 2008). "In Oregon, a Clue on Earliest Americans". The New York Times. p. 17. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ↑ "First Americans". Southern Methodist University-David J. Meltzer, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. Archived from the original on 2009-11-01.

- 1 2 Logan, F. Donald (2005). The Vikings in history. Taylor & Francis. pp. 49–50. ISBN 9780415327565. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ↑ Whitehouse, David (9 June 2003). "When humans faced extinction". BBC Online. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ↑ Max Planck Institute, Department of Human Evolution, Field Projects - Jebel Irhoud

- ↑ http://in-africa.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Spoor-et-al-1998-AJPA-path-SINGA.pdf

- ↑ http://in-africa.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Late-Middle-early-Upper-Pleistocene-African-human-fossils.pdf

- ↑ Kamrani, Kambiz (January 27, 2011). "125,000 Year Old Hand Axes From Jebel Faya, UAE". Anthropology.net. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ↑ Hirst, K. Kris. "Klasies River Caves – Middle Paleolithic South Africa". About.com. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Churchill, SE; Pearson, OM; Grine, FE; Trinkaus, Erik; Holliday, TW (1996). "Morphological affinities of the proximal ulna from Klasies River main site: archaic or modern?". Journal of Human Evolution. 31 (3): 213. doi:10.1006/jhev.1996.0058.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, S. (2003). Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World. ISBN 1841196975.

- ↑ Yellen, JE; Brooks, AS; Cornelissen, E; Mehlman, MJ; Stewart, K (28 April 1995). "A middle stone age worked bone industry from Katanda, Upper Semliki Valley, Zaire". Science. 268 (5210): 553–556. Bibcode:1995Sci...268..553Y. doi:10.1126/science.7725100. PMID 7725100.

- ↑ Balter, Michael (5 March 2010). "Of Two Minds About Toba's Impact," Science 327 (5970): 1187-1188

- ↑ Mijares, Armand. "Callao Man". University of the Philippines Diliman. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ↑ http://www.academia.edu/369255/The_Cyrenaican_Prehistory_Project_2010_the_fourth_season_of_investigations_of_the_Haua_Fteah_cave_and_its_landscape_and_further_results_from_the_2007-2009_fieldwork

- ↑ http://in-africa.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Vermeersch-et-al-1998-Antiq-Taramsa-Hill.pdf

- ↑ "Archaeological Theory; Taiwan Seen As Ancient Pacific Rim". Free China Journal [a.k.a. Taiwan Journal, Taiwan Today]. 19 November 1990. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ↑ Santos, G.M.; et al. (2003). "A revised chronology of the lowest occupation layer of Pedra Furada Rock Shelter, Piauı́, Brazil: the Pleistocene peopling of the Americas". Quaternary Science Reviews. 22 (21–22): 2303–2310. Bibcode:2003QSRv...22.2303S. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(03)00205-1. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ↑ Bowler JM, Johnston H, Olley JM, Prescott JR, Roberts RG, Shawcross W, Spooner NA.; Johnston; Olley; Prescott; Roberts; Shawcross; Spooner (2003). "New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia". Nature. 421 (6925): 837–40. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..837B. doi:10.1038/nature01383. PMID 12594511.

- ↑ Turney, C. S. M., M. I. Bird, L. K. Fifield, R. G. Roberts, M. Smith, C. E. Dortch, R. Grun, E. Lawson, L. K. Ayliffe, G. H. Miller, J. Dortch and R.G. Cresswell (2001). "Early Human Occupation at Devil's Lair, Southwestern Australia 50,000 Years Ago". Quaternary Research. 55 (1): 3–13. Bibcode:2001QuRes..55....3T. doi:10.1006/qres.2000.2195.

- ↑ Hiscock, Peter (2008). The Archaeology of Ancient Australia. Taylor & Francis. p. 44. ISBN 9780415338103.

- ↑ Norton, Christopher J.; David R. Braun (2010). Asian Paleoanthropology: From Africa to China and Beyond. Springer. p. 194. ISBN 9789048190942.

- ↑ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/08/120820152204.htm

- ↑ Gugliotta, Guy (July 2008). "The Great Human Migration". Smithsonian: 2.

- ↑ Higham, Tom; Compton, Tim; Stringer, Chris; Jacobi, Roger; Shapiro, Beth; Trinkaus, Eric; Chandler, Barry; Gröning, Flora; Collins, Chris; Hillson, Simon; O’Higgins, Paul; FitzGerald, Charles; Fagan, Michael (24 Nov 2011). "The earliest evidence for anatomically modern humans in northwestern Europe". Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 479 (7374): 521–524. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..521H. doi:10.1038/nature10484. PMID 22048314. Retrieved 2012-04-19. Lay summary – BBC News (2011-11-02).

- ↑ Wilford, John Noble (29 May 2012). "Flute's Revised Age Dates the Sound of Music Earlier". New York Times. p. D4. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ↑ Kniežaitė, Milda (2016-06-29). "Šnaukštų karjere – sensacingas radinys". Lietuvos žinios (in Lithuanian).

- ↑ O'Connor, Sue; Rintaro Ono; Chris Clarkson (25 Nov 2011). "Pelagic Fishing at 42,000 Years Before the Present and the Maritime Skills of Modern Humans". Science Magazine. 334 (6059): 1117–1121. doi:10.1126/science.1207703. Retrieved 8 Dec 2013.

- ↑ "Ancient human unearthed in China". BBC News. 2 April 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ↑ Paton, Robert. "Draft Final Archaeology Report on the Test Excavations of the Jordan River Levee Site Southern Tasmania" (PDF). DPIWE. p. 2. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ↑ Ng, Stephen. "Hong Kong Archaeology". HKAS. p. 1. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Barker, Graeme; et al. (2007). "The 'human revolution' in lowland tropical Southeast Asia: the antiquity and behavior of anatomically modern humans at Niah Cave (Sarawak, Borneo)". Journal of Human Evolution. Elsevier. 52 (3): 243–261. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.08.011. PMID 17161859. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ↑ Fong, Durie Rainer (10 April 2012). "Archaeologists hit 'gold' at Mansuli". The Star. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ↑ Trinkaus, E; Moldovan, O; Milota, S; Bîlgăr, A; Sarcina, L; Athreya, S; Bailey, SE; Rodrigo, R; et al. (2003). "An early modern human from the Peştera cu Oase, Romania". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (20): 11231–11236. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10011231T. doi:10.1073/pnas.2035108100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 208740

. PMID 14504393.

. PMID 14504393. - ↑ Wilford, John Noble (2 Nov 2011). "Fossil Teeth Put Humans in Europe Earlier Than Thought". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ↑ Deraniyagala, Siran U. "Pre- and Protohistoric settlement in Sri Lanka". XIII U. I. S. P. P. Congress Proceedings- Forli, 8 – 14 September 1996. International Union of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ↑ Cinq-Mars, Jacques. "Significance of the Bluefish Caves in Beringian Prehistory". Canadian Museum of Civilization. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ↑ "Canada's First Nations: Habitation and Settlement". University of Calgary. 2000. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Suzuki, Hisashi; Kazuro Hanihara; et al. (1982). "The Minatogawa Man: The Upper Pleistocene Man from the Island of Okinawa". Bulletin of the University Museum. University of Tokyo. 19. Chapter 1.

- ↑ Clottes, Jean (2003). Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times. Paul G. Bahn (translator). University of Utah Press. ISBN 0874807581.

- ↑ Lovgren, Stefan (19 May 2005). "Prehistoric Bones Point to First Modern-Human Settlement in Europe". National Geographic. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ↑ Wickler, Stephen; Matthew Spriggs (1988). "Pleistocene human occupation of the Solomon Islands, Melanesia". Antiquity. 62 (237): 703–706. Retrieved 18 Nov 2012.

- ↑ Duarte; Maurício, J; Pettitt, PB; Souto, P; Trinkaus, E; Van Der Plicht, H; Zilhão, J; et al. (1999). "The early Upper Paleolithic human skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and modern human emergence in the Iberian Peninsula". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. PNAS. 96 (13): 7604–7609. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.7604D. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7604. PMC 22133

. PMID 10377462. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

. PMID 10377462. Retrieved 2009-06-21. - ↑ Sineo, Luca; et al. (2002). "I resti umani della Grotta di S. Teodoro (Messina): datazione assoluta con il metodo della spettrometria gamma diretta (U/Pa)". Antropo. 2: 9–16. Retrieved 18 Dec 2012.

- ↑ University Of South Carolina (2004). "New Evidence Puts Man In North America 50,000 Years Ago". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 15 Apr 2014.

- ↑ Heinz History Center: Rockshelter Artifacts, Heinz History Center. Pittsburgh, PA. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ↑ "Monte Verde Archaeological Site". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Bonavia, Duccio (1991). Perú, hombre e historia. I. Edubanco. p. 89.

- ↑ Simmons, Alan H. (2001). "The first humans and last pygmy hippopotami of Cyprus". In Swiny, Stuart. The earliest prehistory of Cyprus: From colonization to exploitation (PDF). Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute Monograph Series. 2. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research. pp. 1–18. Retrieved 2012-04-24.

- ↑ Fugelsnes, Elin. "I Fred Flintstones rike" (in Norwegian). Forskning.no (NTNU). Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ↑ Welcome Argentina: Expediciones Arqueológicas en Los Toldos y en Piedra Museo (Spanish)

- ↑ Mateu; et al. (1997). "A tale of two islands: population history and mitochondrial DNA sequence variation of Bioko and São Tomé, Gulf of Guinea". Annals of Human Genetics. 61 (6): 507–518. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.1997.6160507.x. PMID 9543551.

- ↑ "Mount Sandel, County Londonderry". BBC Online. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ↑ "Mount Sandel – earliest human settlement in Ireland" (PDF). University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ↑ Poska, Anneli; Leili Saarse (1996). "Prehistoric human disturbance of the environment induced from Estonian pollen records: a pilot study". Proceedings of the Estonian Academy of Sciences, Geology. Estonian Academy Publishers. 45 (3): 152. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ↑ Mourer, C. & R.; Leili Saarse (1977). "Laang Spean and the prehistory of Cambodia". Modern Quaternary Research in Southeast Asia. 3: 29–56.

- ↑ Pitul'ko, V. V. (1993). "An Early Holocene Site in the Siberian High Arctic". Arctic Anthropology. 30 (1): 13–21. JSTOR 40316326.

- ↑ Pitul'ko, V. V.; Kasparov, A. V. (1996). "Ancient arctic hunters: material culture and survival strategy". Arctic Anthropology. 33 (1): 1–36. JSTOR 40316394.

- ↑ "The Fire Caves of Nanumaga". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. 13 April 1987.

- ↑ "Ghar Dalam Phase," Malta National Museum of Archeology

- ↑ Rouse, Irving; Louis Allaire (1978). "Caribbean Chronology". In RE Taylor and CW Meighan. Chronologies in New World Archaeology. New York: Academic Press. pp. 431–481. ISBN 0126857504.

- ↑ Siegel, Peter E.; et al. (2005). "Environmental and Cultural Correlates in the West Indies: A View from Puerto Rico". In Peter E. Siegel. Ancient Borinquen: Archaeology and Ethnohistory of Native Puerto Rico. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. p. 113. ISBN 0817352384.

- ↑ Childress, David Hatcher (1998). Ancient Micronesia & the Lost City of Nan Madol: Including Palau, Yap, Kosrae, Chuuk & the Marianas. Adventures Unlimited Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-932813-49-7.

- ↑ "Ancient human genome sequence of an extinct Palaeo-Eskimo". Nature Publishing Group. 2010. pp. 463, 757–762. doi:10.1038/nature08835. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- ↑ Mary-Rousselière, Guy (1976). "The Paleoeskimo in Northern Baffinland". Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology. Society for American Archaeology. 31: 40–41. JSTOR 40495394.

- ↑ Dikov, N. N. (1988). "The Earliest Sea Mammal Hunters of Wrangell Island". Arctic Anthropology. 25 (1): 80–93. JSTOR 40316156.

- ↑ Kirch, Patrick Vinton (1997). The Lapita Peoples: Ancestors of the Oceanic World. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers. p. 273. ISBN 9781577180364.

- ↑ Nunn, Patrick D.; et al. (Oct 2004). "Early Lapita settlement site at Bourewa, southwest Viti Levu Island, Fiji". Archaeology in Oceania. 39 (3): 139–143. JSTOR 40387292.

- ↑ Maca-Meyer N, Arnay M, Rando JC, et al. (February 2004). "Ancient mtDNA analysis and the origin of the Guanches". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 12 (2): 155–62. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201075. PMID 14508507.

- ↑ Bedford, Stuart (2006). Pieces of the Vanuatu Puzzle: Archaeology of the North, South and Centre. Canberra: Pandanus Books. p. 273. ISBN 1-74076-093-X.

- ↑ Green, Roger C.; Leach, Helen M. (1989). "New Information for the Ferry Berth Site, Mulifanua, Western Samoa". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 98 (3): 319–330. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- ↑ Kirch, Patrick Vinton (1997). Feathered Gods and Fishhooks: An Introduction to Hawaiian Archaeology and Prehistory. University of Hawaii Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-8248-1938-1.

- ↑ "The cryptic past of Madagascar – Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute". Sanger Institute. 4 May 2005. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ↑ Hannon, G; Bradshaw, Richard H.W. (2000). "Impacts and Timing of the First Human Settlement on Vegetation of the Faroe Islands". Quaternary Research. 54 (3): 404–413. Bibcode:2000QuRes..54..404H. doi:10.1006/qres.2000.2171. ISSN 0033-5894.

- ↑ Berman, Mary Jane; Pearsall, Deborah M. (2000). "Plants, People, and Culture in the Prehistoric Central Bahamas: A View from the Three Dog Site, an Early Lucayan Settlement on San Salvador Island, Bahamas". Latin American Antiquity. 11 (3): 223–225. doi:10.2307/972175. JSTOR 972175.

- ↑ Steadman, D. W.; Pahlavan, D. S. (Oct 1992). "Extinction and biogeography of birds on Huahine, Society Islands, French Polynesia". Geoarchaeology. 7 (5): 449–483. doi:10.1002/gea.3340070503.

- ↑ Hunt, T. L., Lipo, C. P., 2006. Science, 1121879. See also "Late Colonization of Easter Island" in Science Magazine. Entire article is also hosted by the Department of Anthropology of the University of Hawaii.

- ↑ Irwin, Geoff; Walrond, Carl (4 March 2009). "When was New Zealand first settled? – The date debate". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Buckley, H.; Tayles, N.; Halcrow, S.; Robb, K.; Fyfe, R. (2009). "The People of Wairau Bar: a Re-examination". Journal of Pacific Archaeology. 1 (1): 1–20.

- ↑ Anderson, Atholl; White, Peter (2001). "Prehistoric Settlement on Norfolk Island and its Oceanic Context" (PDF). Records of the Australian Museum (Supplement 27): 135–141. doi:10.3853/j.0812-7387.27.2001.1348. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- 1 2 3 Macnaughtan, Don (2001). "Bibliography of Prehistoric Settlement on Norfolk Island, the Kermadecs, Lord Howe, and the Auckland Islands". Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ Rodrigues, João Damião (1995). "Sociedade e administração nos Açores (século XV-XVIII) : o caso de Santa Maria" (PDF). Arquipélago. História (in Portuguese) (2 ed.). Ponta Delgada (Azores), Portugal: University of the Azores. 1 (2): 33–63. ISSN 0871-7664.

- ↑ Newitt, M. D. D. (2005). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400-1668. Psychology Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780415239806.

- ↑ http://sainthelenaisland.info/briefhistory.htm

- ↑ de Wulf, Valérie (2014). Histoire de l'île d'Annobon (Guinée Equatoriale) et de ses habitants: du XVè au XIXè siècle, Volume 1. Editions L'Harmattan. p. 338. ISBN 9782343033976.

- ↑ McFadgen, B. G. (March 1994). "Archaeology and Holocene sand dune stratigraphy on Chatham Island". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 24 (1): 17–44. doi:10.1080/03014223.1994.9517454.

- ↑ Ellis, Richard (1991). Men & Whales. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 62. ISBN 1-55821-696-0.

- ↑ "Cultural Heritage Structures and Sites in Mauritius". Portal of the Republic of Mauritius. Government of Mauritius. 2005. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ↑ Leguat, François (1891). The voyage of François Leguat of Bresse, to Rodriguez, Mauritius, Java, and the Cape of Good Hope. 1. Edited and annotated by Samuel Pasfield Oliver. London: Hakluyt Society. p. 55.

- ↑ Goebel, Julius (August 1971). The struggle for the Falkland Islands: a study in legal and diplomatic history. Kennikat Press. ISBN 978-0-8046-1390-3. Retrieved 17 March 2011. pp. 226

- ↑ McAteer, William (1991). Rivals in Eden: a history of the French settlement and British conquest of the Seychelles Islands, 1742-1818. Book Guild. ISBN 0863324967. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ "Tristan d'Acunha, etc.: Jonathan Lambert, late Sovereign thereof". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. 4 (21): 280–285. Dec 1818.

- ↑ Oda, Shizuo (1984). "Archaeology of the Ogasawara Islands" (PDF). Asian Perspectives. 24 (1): 111–138.

- ↑ "Chronique Geographique". Bulletin de géographie d'Aix-Marseille. Société de Géographie de Marseille. 17: 184. 1893. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ Les oubliés de l'île Saint-Paul, by Daniel Floch. 1982.

- ↑ Headland, R. K. (1989). Chronological List of Antarctic Expeditions and Related Historical Events. Cambridge University Press. p. 188. ISBN 9780521309035.

- ↑ Jan Mayen Information by Rolf Stange

- ↑ Mills, William J. (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 531. ISBN 1576074226. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

External links

- Atlas of the Human Journey – National Geographic

- Journey of Mankind – Genetic Map – Bradshaw Foundation