Tombstone, Arizona

| Tombstone | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| Tombstone, Arizona | ||

| ||

| Motto: The Town Too Tough To Die | ||

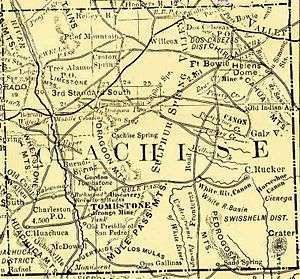

Location in Cochise County and the state of Arizona | ||

| Coordinates: 31°42′57″N 110°3′53″W / 31.71583°N 110.06472°WCoordinates: 31°42′57″N 110°3′53″W / 31.71583°N 110.06472°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Arizona | |

| County | Cochise | |

| Founded | 1879 | |

| Incorporated | 1881 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Dusty Escapule | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 4.3 sq mi (11.2 km2) | |

| • Land | 4.3 sq mi (11.2 km2) | |

| • Water | 0.0 sq mi (0.0 km2) | |

| Elevation | 4,541 ft (1,384 m) | |

| Population (2010)[1] | ||

| • Total | 1,380 | |

| • Estimate (2014)[2] | 1,322 | |

| • Density | 320/sq mi (120/km2) | |

| Time zone | MST (no DST) (UTC-7) | |

| ZIP code | 85638 | |

| Area code | 520 | |

| FIPS code | 04-74400 | |

| GNIS feature ID | 12590 | |

| Website |

www | |

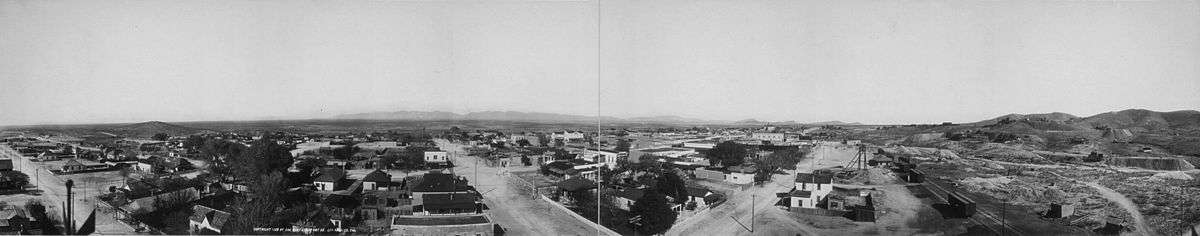

Tombstone is a historic western city in Cochise County, Arizona, United States, founded in 1879 by Ed Schieffelin in what was then Pima County, Arizona Territory. It was one of the last wide-open frontier boomtowns in the American Old West. The town prospered from about 1877 to 1890, during which time the town's mines produced US$40 to $85 million in silver bullion, the largest productive silver district in Arizona. Its population grew from 100 to around 14,000 in less than seven years. It is best known as the site of the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral and now draws most of its revenue from tourism.

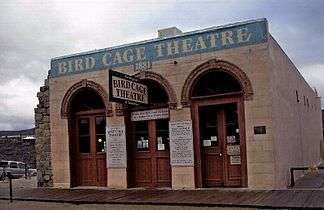

The town was established on a mesa above the Tough Nut Mine. Within two years of its founding, although far distant from any other metropolitan area, Tombstone boasted a bowling alley, four churches, an ice house, a school, two banks, three newspapers, and an ice cream parlor, alongside 110 saloons, 14 gambling halls, and numerous dance halls and brothels. All of these were situated among and on top of a large number of dirty, hardscrabble mines. The gentlemen and ladies of Tombstone attended operas presented by visiting acting troupes at the Schieffelin Hall opera house, while the miners and cowboys saw shows at the Bird Cage Theatre, "the wildest, wickedest night spot between Basin Street and the Barbary Coast".

Under the surface were tensions that grew into deadly conflict. The mining capitalists and the townspeople were largely Republicans from the Northern states. Many of the ranchers (some of whom—like the Clantons—were also rustlers and/or other criminal varieties) were Confederate sympathizers and Democrats. The booming city was only 30 miles (48 km) from the U.S.–Mexico border and was an open market for beef stolen from ranches in Sonora, Mexico, by a loosely organized band of outlaws known as The Cowboys. The Earp brothers—Virgil, Wyatt, Morgan and Warren—arrived in December 1879 and mid-1880. They had ongoing conflicts with Ike, Billy Clanton, Frank, Tom McLaury, and other Cowboys members. The Cowboys repeatedly threatened the Earps over many months until the conflict escalated into a shootout on October 26, 1881. The now-famous gunfight is often portrayed as occurring at the O.K. Corral, but the actual gunfight was on Fremont Street a block or two away.

In the mid-1880s, the silver mines penetrated the water table and the mining companies made significant investments in specialized pumps. A fire in 1886 destroyed the Grand Central hoist and the pumping plant, and it was unprofitable to rebuild the costly pumps. The city nearly became a ghost town, saved only because it was the Cochise County seat until 1929. The city's population dwindled to a low of 646 in 1910, but grew to 1,380 by 2010.[3] It has frequently been noted on lists of unusual place names.[4][5]

History

.jpg)

Founding

Ed Schieffelin was briefly a scout for the U. S. Army headquartered at Camp Huachuca. Schieffelin frequently searched the wilderness looking for valuable ore samples. At the Santa Rita mines in nearby Santa Cruz Valley, three superintendents had been killed by Indians. When friend and fellow Army Scout Al Sieber learned what Schieffelin was up to, he is quoted as telling him, "The only rock you will find out there will be your own tombstone".[6] Another account reported Schieffelin's friends told him, "Better take your coffin with you; you will find your tombstone there, and nothing else."[7]

In 1877, Schieffelin used Brunckow's Cabin as a base of operations to survey the country. After many months, while working the hills east of the San Pedro River, he found pieces of silver ore in a dry wash[8] on a high plateau called Goose Flats.[9] It took him several more months to find the source. When he located the vein, he estimated it to be fifty feet long and twelve inches wide.[10] Schieffelin's legal mining claim was sited near Lenox's grave site, and on September 21, 1877, Schieffelin filed his first claim and fittingly named his stake Tombstone.[8][11]

When the first claims were filed, the initial settlement of tents and wooden shacks was located at Watervale, near the Lucky Cuss mine, with a population of about 100.[12] Former Territorial Governor Anson P. K. Safford offered financial backing for a share of the mining claim, and Schieffelin, his brother Al, and their partner Richard Gird formed the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company and built a stamping mill. When the mill was being built, U.S. Deputy Mineral Surveyor Solon M. Allis finished surveying the new town's site, which was revealed on March 5, 1879, to an eager public.[13] The tents and shacks near the Lucky Cuss were moved to the new town site on Goose Flats, a mesa above the Toughnut at 4,539 feet (1,383 m) above sea level and large enough to hold a growing town. Lots were immediately sold on Allen Street for $5.00 each. The town soon had some 40 cabins and about 100 residents. At the town's founding in March 1879, it took its name from Schieffelin's initial mining claim. By fall 1879, a few thousand hardy souls were living in a canvas and matchstick camp perched amidst the richest silver strike in the Arizona Territory.[12]

When Cochise County was formed from the eastern portion of Pima County on February 1, 1881, Tombstone became the new county seat. Telegraph service to the town was established that same month. In early March 1880, the Schieffelins' Tombstone Mining and Milling Company which owned the Tough Nut Mine, among others, was sold to investors from Philadelphia.[14] Two months later, it was reported that the Tough Nut Mine was working a vein of silver ore 90 feet (27 m) across that assayed at $170 per ton, with some ore assaying at $22,000 a ton.[14]

On September 9, 1880, the richly appointed Grand Hotel was opened, adorned with fine oil paintings, thick Brussels carpets, toilet stands, elegant chandeliers, silk-covered furniture, walnut furniture, and a kitchen with hot and cold running water.[15] At the height of the silver mining boom, when the population was about 10,000, the city was host to Kelly's Wine House, featuring 26 varieties of wine imported from Europe, a beer imported from Colorado named "Coors", cigars, a bowling alley, and many other amenities common to large cities.

Early conflicts

Under the surface were other tensions aggravating the simmering distrust. Most of the Cowboys were Confederate sympathizers and Democrats from Southern states, especially Texas. The mine and business owners, miners, townspeople and city lawmen including the Earps were largely Republicans from the Northern states. There was also the fundamental conflict over resources and land, of traditional, Southern-style, "small government" agrarianism of the rural Cowboys contrasted to Northern-style industrial capitalism.[16]

In the early 1880s, smuggling and theft of cattle, alcohol, and tobacco across the U.S./Mexico border about 30 miles (48 km) from Tombstone were common. The Mexican government taxed these items heavily and smugglers earned a handsome profit by sneaking these products across the border. The illegal cross-border smuggling contributed to the lawlessness of the region. Many of these crimes were carried out by outlaw elements labeled "Cow-boys", a loosely organized band of friends and acquaintances who teamed up for various crimes and came to each other's aid. The San Francisco Examiner wrote in an editorial, "Cowboys [are] the most reckless class of outlaws in that wild country...infinitely worse than the ordinary robber."[17] At that time during the 1880s in Cochise County it was an insult to call a legitimate cattleman a "Cowboy". Legitimate cowmen were referred to as cattle herders or ranchers.[18] The Cowboys were nonetheless welcome in town because of their free-spending habits, but shootings were common.

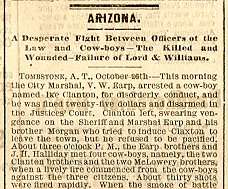

Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

On the evening of March 15, 1881, three Cowboys attempted to rob a Kinnear & Company stagecoach carrying US$26,000 in silver bullion (about $639,000 in today's dollars) en route from Tombstone to Benson, Arizona, the nearest railroad freight terminal.[19]:180 Near Drew's Station, just outside Contention City, the popular and well-known driver Eli "Budd" Philpot and a passenger named Peter Roerig riding in the rear dickey seat were both shot and killed. Deputy U.S. Marshal Sheriff Virgil Earp and his temporary deputies and brothers Wyatt Earp and Morgan Earp pursued the Cowboys suspected of the murders. This set off a chain of events that culminated on October 26, 1881 in the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, during which the lawmen killed Tom McLaury, Frank McLaury, and Billy Clanton.

The gunfight was the result of a personal, family, and political feud. Three months later on the evening of December 28, 1881, Virgil Earp was ambushed and seriously wounded on the streets of Tombstone by hidden assailants shooting from the second story of an unfinished building. Although identified, the suspects provided witnesses who supplied alibis, and the men were not prosecuted. On March 18, 1882, Morgan Earp was killed by a shot that struck his spine while playing billiards at 10:00 p.m. Once again, the assailants were named but escaped arrest due to legal technicalities. Wyatt Earp, concluding that legal justice was out of reach, led a posse that pursued and killed four of the men they held responsible on what became known as the Earp Vendetta Ride.[20]

After the Earp family left Arizona, much of the Cowboy related crime subsided. John Slaughter was elected Cochise County Sheriff in 1886 and served two terms. He hired Burt Alford, who as a 15-year-old boy had witnessed the shootout between the Earps and Cowboys. Alford served very effectively for three years until he began to drink heavily and began to associate with outlaws.[21]

Boothill Graveyard

Tom McLaury, Frank McLaury, and Billy Clanton, killed in the O.K. Corral shootout, are among those buried in the town's Boothill Graveyard. Of the number of pioneer Boot Hill cemeteries in the Old West, so named because most of those buried in them had "died with their boots on", Boothill in Tombstone is one of the best-known.[22]

Silver mining

Tombstone boomed, but founder Ed Schieffelin was more interested in prospecting than owning a mine. Ed was one-third partners with his brother Al Schieffelin and Richard Gird. There were several hundred mining claims near Tombstone, although the most productive were immediately south of town. These included the Contention, Grand Central, Lucky Cuss, Emerald, Silver Thread, and Toughnut. Due to the lack of readily available water near town, mills were built along the San Pedro River about 9 miles (14 km) away, leading to the establishment of several small mill towns, including Charleston, Contention City, and Fairbank.[23]

Schieffelin left Tombstone to find more ore and when he returned four months later,[24] Gird had lined up buyers for their interest in the Contention claim, which they sold for $10,000. It would later yield millions in silver. They sold a half-interest in the Lucky Cuss, and the other half turned into a steady stream of money. Al and Ed Schieffelin later sold their two-thirds interest in the Tough Nut for US$1 million, and sometime later Gird sold his one-third interest for the same amount.[25]:20

There are widely varying estimates of the value of gold and silver mined during the course of Tombstone's history. The Tombstone mines produced 32 million troy ounces (1,000 metric tons) of silver, more than any other mining district in Arizona.[26] In 1883, writer Patrick Hamilton estimated that during the first four years of activity the mines produced about USD $25,000,000 (approximately $636 million today). Other estimates include USD $40[9] to USD $85 million[27] (about $1.06 billion to $2.24 billion today). Renewed mining is planned for the area.[28]

One of the byproducts of the vast riches being produced, lawsuits became very prevalent. Between 1880 and 1885 the courts were clogged with a large number of cases, many of them about land claims and properties. As a result, lawyers began to settle in Tombstone and became even wealthier than the miners and those who financed the mining. In addition, because many of the lawsuits required expert analysis of the underground, many geologists and engineers found employment in Tombstone and settled there. In the end, a thorough mapping of the area was completed by experts which resulted in maps documenting Tombstone's mining claims better than any other mining district of the West.[29]

Mining was an easy task at Tombstone in the early days, ore being rich and close to the surface. One man could pull out ore equal to what three men produced elsewhere.[30] Some residents of Tombstone became quite wealthy and spent considerable money during its boom years. Tombstone's first newspaper, the Nugget, was established in the fall of 1879. The Tombstone Epitaph was founded on May 1, 1880. As the fastest growing boomtown in the American Southwest, the silver industry and attendant wealth attracted many professionals and merchants who brought their wives and families. With them came churches and ministers. They brought a Victorian sensibility and became the town's elite. Many citizens of Tombstone dressed well, and up-to-date fashion could be seen in this growing mining town.[31] Visitors expressed their amazement at the quality and diversity of products that were readily available in the area. The men who worked the mines were largely European immigrants. The Chinese did the town's laundry and provided other services. The Cowboys ran the countryside and stole cattle from haciendas across the international border in Sonora, Mexico.

When the railroad was not built into Tombstone as had been planned, the increasingly sophisticated city of Tombstone remained relatively isolated, deep in a Federal territory that was largely an unpopulated desert and wilderness. Tombstone and its surrounding countryside also became known as one of the deadliest regions in the West. Water was hauled in until the Huachuca Water Company, funded in part by investors like Dr. George E. Goodfellow, built a 23-mile-long (37 km) pipeline from the Huachuca Mountains in 1881. No sooner was a pipeline completed than Tombstone's silver mines struck water.[12]

City growth and decline

Due to poor building practices and poor fire protection common to boomtown construction, Tombstone was hit by two major fires. On June 22, 1881, the first fire destroyed 66 businesses making up the eastern half of the business district. The fire began when a lit cigar ignited a barrel of whiskey in the Arcade Saloon.[32][33]

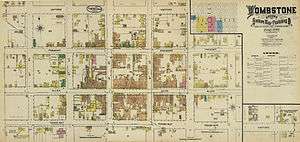

By mid-1881 there were fancy restaurants, Vogan's Bowling Alley,[34] four churches—Catholic, Episcopal, Presbyterian, and Methodist[12]—an ice house, a school, the Schieffelin Hall opera house, two banks, three newspapers, and an ice cream parlor, alongside 110 saloons, 14 gambling halls,[35][36] several Chinese restaurants, French, two Italian, numerous Mexican, several upscale "Continental" establishments, and many "home cooking" hot spots including Nellie Cashman's famous Rush House and numerous brothels all situated among and on top of a number of dirty, hardscrabble mines.[37] The Arizona Telephone Company began installing poles and lines for the city's first telephone service on March 15, 1881.[38]

Capitalists from the northeastern United States bought many of the leading mining operations. The mining itself was carried out by immigrants from Europe, chiefly Cornwall, Ireland and Germany.[39] Chinese and Mexican labor provided services including laundry, construction, restaurants, hotels, and more.

The mines and stamping mills ran three shifts.[12] Miners were paid union wages of USD$4.00 per day working six 10-hour shifts per week. The approximately 6,000 men working in Tombstone generated more than $168,000 a week (approximately $4,273,800 today) in income.[40] The mostly young, single, male population spent their hard-earned cash on Allen Street, the major commercial center, open 24 hours a day.

The respectable folks saw traveling theater shows at Schieffelin Hall, opened on June 8, 1881. On December 25, 1881, the Bird Cage Theatre opened on Allen Street, offering the miners and Cowboys their kind of bawdy entertainment. In 1882, The New York Times reported that "the Bird Cage Theatre is the wildest, wickedest night spot between Basin Street and the Barbary Coast."[41] The Bird Cage remained open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year until it closed its doors in 1889.[42] Respectable women stayed on the north side of Allen Street. The prostitutes worked the saloons on the south side and in the southeast quarter of the town, as far as possible from the proper residential section north of Fremont Street.[12]

By late 1881 Tombstone had more than 7,000 citizens, excluding all Chinese, Mexicans, women and children residents. At the height of the town's boom, the official population reached about 10,000, with several thousand more uncounted.[12] In 1882, the Cochise County Courthouse was built at a cost of around $45,000.[42]

On May 25, 1882, another, more destructive fire started in a Chinese laundry on Fifth Street between Toughnut and Allen streets. It destroyed the Grand Hotel and the Tivoli Saloon before it jumped Fremont Street, destroying more than 100 businesses and most of the business district. Lacking enough water to put out the flames, buildings in the fire's path were dynamited to deny the fire fuel. Total damages were estimated to be USD $700,000, far more than the estimated $250,000 insurance coverage. But rebuilding started right away nonetheless.[33][43]

In March 1883, along one short stretch of Allen Street, there were drinking establishments in two principal hotels, the Eagle Brewery, Cancan Chop-House, French Rotisserie, Alhambra, Maison Dore, City of Paris, Brown's Saloon, Fashion Saloon, Miners' Home, Kelly's Wine-House, the Grotto, the Tivoli, and two more unnamed saloons.[44]

Mines strike water

The Tough Nut Mine first experienced seepage in 1880. In March 1881, the Sulphuret Mine struck water at 520 feet (160 m). A year later, in March 1882, miners in a new shaft of the Grand Central Mine hit water at 620 feet (190 m). The flow wasn't at first large enough to stop work, but experienced miners thought the water flow would increase, and it did. Soon constant pumping with a 4 inches (100 mm) pump was insufficient. The silver ore deposits they sought were soon underwater.[43]

Several mine managers traveled to San Francisco and met with the principal owners of the Contention Mine. They talked about options for draining the mines, and found the only system available for pumping water out of mines below 400 feet (120 m) was the Cornish engine which had been used at the Comstock Lode in the 1870s.[43] They bought and installed the huge Cornish engines in the Contention and Grand Central mines. By mid-February 1884, the engines were removing 576,000 US gallons (2,180,000 l; 480,000 imp gal) of water every twenty-four hours. The city merchants celebrated the continued success of mining and the transfer of funds to their businesses.[43] The Contention and the Grand Central found that their pumps were draining the mining district, benefiting other mines as well, but the other companies refused to pay a proportion of the expense.[45]

On May 26, 1886, the Grand Central hoist and pumping plant burned. The fire was so intense that the metal components of the Cornish engine melted and warped. The headworks of the main mine shaft were also destroyed. Shortly afterward, the price of silver slid to 90 cents an ounce. The mines that remained operational laid off workers. Individuals who had thought about leaving Tombstone when the mine flooding started now took action. The price of silver briefly recovered for a while and a few mines began producing again, but never at the level reached in the early 1880s.[43]

Tourism

The U.S. census recorded fewer than 1,900 residents in 1890 and fewer than 700 residents in 1900. Tombstone was saved from becoming a ghost town partly because it remained the Cochise County seat until 1929, when county residents voted to move county offices to nearby Bisbee. The classic Cochise County Courthouse and adjacent gallows yard in Tombstone are preserved as a museum.

Currently, tourism and western memorabilia are the main commercial enterprises; a July 2005 CNN article notes that Tombstone receives approximately 450,000 tourist visitors each year. This is about 300 tourists/year for each permanent resident. In contrast to its heyday, when it featured saloons open 24 hours and numerous houses of prostitution, Tombstone is now a staid community with few businesses open late. Tombstone and surrounding areas have a variety of lodging options, restaurants, and attractions. The town is located near other historic sites of interest, including Bisbee and the San Pedro Riparian area. Tombstone is a short drive away from Sierra Vista, which is considered the shopping hub of Cochise County.[46]

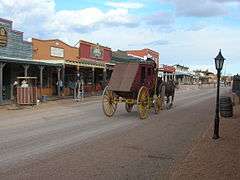

East Allen Street is the center of Tombstone's tourist attractions, featuring three blocks of shaded boardwalks lined with gift shops, saloons, and eateries. Allen Street's historic district is closed to motor traffic from 3rd Street, the location of the city park and OK Corral, to 6th Street, where the Bird Cage Theatre is located. Additional sites of interest can be found throughout the city, even out on Highway 80, where Boot Hill Cemetery is found.

The Tombstone Western Film Festival was held there from 2001-2005.

Performance events

The historic O.K. Corral has been preserved but is now surrounded by a wall. Mannequins are used to depict the location of the participants as recorded by Wyatt Earp. Visitors may pay to see a reenactment of the gunfight. Until April 2013, the reenactment was performed at 2:00 p.m. each day,[47] but a new version is now performed three times daily at 12:00, 2:00, and 3:30 PM. Fremont Street (modern Arizona Highway 80), where portions of the gunfight took place, is open to the public.

Performance events help preserve the town's Wild West image and expose it to new visitors. Helldorado Days is Tombstone's oldest festival[48] and celebrates the community's wild days of the 1880s. Started in 1929 (coincidentally the year Wyatt Earp died), the festival is held on the third weekend of every October, near the anniversary date of the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, and consists of gunfight reenactment shows, street entertainment, fashion shows and a family-oriented carnival. Tombstone's Main Event: A Tragedy at the O.K. Corral, a stage play by Stephen Keith, was presented inside the O.K. Corral until 2013. It depicted the Cowboys' version of events in which the Earps shot the Cowboys as they attempted to surrender. The new reenactment, titled simply "The Gunfight", began its run in May 2013. The show runs thirty minutes, three times daily. "The Gunfight", written and directed by Wyatt Earp historian Timothy W. Fattig, portrays the infamous shootout as an inevitable consequence of the protagonists' bravado. Performers from all local stage shows can be seen on and around Allen Street every day.

World's largest rose bush

According to Guinness, the world's largest rosebush was planted in Tombstone in 1885 and still flourishes in the city's sunny climate. The Lady Banksia rose originated in Scotland. Mary Gee was the wife of mining engineer Henry Gee, who worked for the Vizina Mining Co. Mary's family sent the homesick bride a box of rooted cuttings from her home country. She planted one of the roses by the patio of the Vizina Mining Company's boarding house, the first adobe building in town, located at 4th and Toughnut Street across from the later site of the railroad depot. She and Henry lived in the boarding house when they first arrived in Tombstone.[49][50]

The building was later renamed the Cochise House Hotel, and from 1909 to 1936 it was known as the Arcade Hotel. By the 1930s, the rose bush had grown to shade the entire patio and became a popular site for tourists. The hotel was later renamed the Rose Tree Inn and then the Rose Tree Inn Museum. The museum curator tells visitors that all Banks roses growing in the U.S. today are descendants of the Tombstone rose.[49]

In 1940, the Lady Banksia rose covered about 4,000 sq ft (370 m2).[51] As of 2014, the rose bush covered more than 8,000 sq ft (740 m2) of the roof and garden trellis of the inn, and has a 12 ft (3.7 m) circumference trunk. The rose bush is walled off, and the inn charges admission to view it.[50]

Historic district

The Tombstone Historic District is a National Historic Landmark District. The town's focus on tourism has threatened the town's designation as a National Historic Landmark District, a designation it earned in 1961 as "one of the best preserved specimens of the rugged frontier town of the 1870s and '80s". In 2004, the National Park Service declared that the Tomb's historic designation was threatened, and asked the community to develop an appropriate stewardship program.

31°42′43″N 110°04′08″W / 31.711944°N 110.068889°W

The National Park Service noted inappropriate alterations to the district included:

- Placing "historic" dates on new buildings

- Failing to distinguish new construction from historic structures

- Covering authentic historic elevations with inappropriate materials

- Replacing historic features instead of repairing them

- Replacing missing historic features with conjectural and unsubstantiated materials

- Building incompatible additions to existing historic structures and new incompatible buildings within the historic district

- Using illuminated signage, including blinking lights surrounding historic signs

- Installing hitching rails and Spanish tile-covered store porches when such architectural features never existed within Tombstone

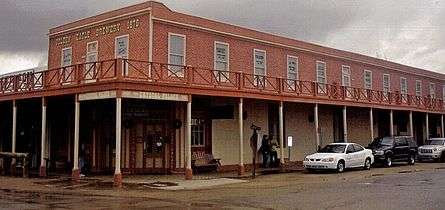

Historical buildings include Schieffelin Hall, the opera house built by Al Schieffelin in 1881, and the Cochise County Courthouse. The courthouse was largely unused and then vacant after the county seat was moved to Bisbee. An attempt was made to turn it into hotel in the 1940s, and when that failed it stood empty until 1955. The Tombstone Restoration Commission acquired the courthouse and developed it as a historical museum that opened in 1959. It features exhibits and thousands of artifacts documenting Tombstone's past.[52]

The Crystal Palace Saloon, including its 45 feet (14 m) long mahogany bar, was rebuilt based on photographs of the original saloon was restored in May 1964 to its 1881 condition. This included large Victorian ceiling lamps and the inlaid‐patterned wood floor.[53]

Geography and geology

The Tombstone District located at 31°42′57″N 110°3′53″W / 31.71583°N 110.06472°W (31.715940, -110.064827)[54] sits atop a mesa (elevation 4,539 feet (1,383 m)) in the San Pedro River valley between the Huachuca Mountains and Whetstone Mountains to the west, and the Mules and the Dragoon Mountains to the east. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 4.3 square miles (11.2 km2), all land.[3]

The silver-bearing Tombstone Hills around the city are caused by a local upheaval of porphyry through a limestone capping.[12]

When actively mined, the silver vein of argentiferous galena (silver-bearing lead) was large and well defined. The silver and lead was easily milled and smelted. The lead content sometimes was as much as 50 per cent of the ore, and assays proved the silver content ran as high as $105.00 per ton in 1881 dollars.[55]

The underlying basement rocks are fine-grained Pinal Schist which is intruded by gneissic granite. The outcrop is in a small area south of the principal mines. The overlying Paleozoic quartzite and limestones rock lies on an unconformity with a total thickness ranging from 4,000 to 5,000 feet (1,200 to 1,500 m), and contains 2,500 to 3,500 feet (760 to 1,070 m) of Mississippian Escabrosa Limestone and the Naco Formation limestone of Pennsylvanian age in the upper formations.[56]

Overlying the Naco Limestone is an unconformable Mesozoic series of conglomerate, thick-bedded quartzites, and shales, with two or three lenses of soft, bluish-gray limestone. Into these formations intrude intruded great bodies of quartz monzonite and by dikes of quartz monzonite-porphyry and diorite-porphyry. Structural faulting occurs throughout the district especially immediately south of Tombstone, where the strata are closely folded.[57]

Tombstone District ores have been produced geologically in three or more ways.

They may have been formed in argentiferous (silver bearing) lead sulfide containing spotty amounts of copper and zinc. These deposits are usually deeply oxidized and enriched by irregular replacement bodies along mineralized fissure zones and anticlinal rolls cut by Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary formations. Ore bodies are often closely associated with newer cross-cutting intrusive dikes of Laramide.

Ore deposits were formed by base metal mineralization occurs with oxidation found in fault and fracture zones in Laramide volcanics and quartz latite porphyry intrusive.

Silver ore was also formed in manganese oxides with some argentiferous deposits in lenticular or pipe-like replacement bodies along fracture and fault zones, usually in Pennsylvanian-Permian era Naco Group limestones.[56][57]

Climate

Tombstone has a typical Arizona semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk/BSh) with three basic seasons. Winter, from October to March, features mild to warm days and chilly nights, with minima falling to under 32 °F or 0 °C on 28.4 nights, although snowfall is almost unknown, with the median being zero and the heaviest monthly fall 14.0 inches or 0.36 metres in January 1916, of which 12.0 inches (0.30 m) fell on January 16. The coldest temperature record in Tombstone has been 3 °F or −16.1 °C on December 8, 1978.

The summer season from April to June is extremely dry and gradually heats up – the hottest temperature on record being 112 °F or 44.4 °C on July 4 of 1989 – before the monsoon season from July to September brings the heaviest rainfall, averaging 6.39 inches (162.3 mm) out of an annual total of 14.10 inches (358.1 mm). The wettest month has been July 2008 when 11.53 inches or 292.9 millimetres fell[58] and fifteen days saw at least 0.04 inches (1.0 mm) of rainfall – though the most such days in a month is eighteen in July 1930. Since 1893 the wettest calendar year has been 1905 with 27.84 inches or 707.1 millimetres and the driest 1924 with 7.36 inches or 186.9 millimetres.[58]

| Climate data for Tombstone, Arizona (1971-2000; extremes 1893-2001) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

96 (36) |

92 (33) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

110 (43) |

112 (44) |

106 (41) |

106 (41) |

100 (38) |

91 (33) |

84 (29) |

112 (44) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 59.5 (15.3) |

63.5 (17.5) |

68.8 (20.4) |

76.6 (24.8) |

85.0 (29.4) |

94.5 (34.7) |

93.3 (34.1) |

90.5 (32.5) |

87.6 (30.9) |

78.3 (25.7) |

67.6 (19.8) |

59.8 (15.4) |

77.1 (25.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 36.1 (2.3) |

38.5 (3.6) |

41.9 (5.5) |

47.3 (8.5) |

54.8 (12.7) |

63.1 (17.3) |

66.5 (19.2) |

65.2 (18.4) |

61.4 (16.3) |

52.4 (11.3) |

42.6 (5.9) |

36.7 (2.6) |

50.5 (10.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 6 (−14) |

11 (−12) |

12 (−11) |

23 (−5) |

31 (−1) |

41 (5) |

50 (10) |

53 (12) |

43 (6) |

27 (−3) |

18 (−8) |

3 (−16) |

3 (−16) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 1.03 (26.2) |

0.74 (18.8) |

0.71 (18) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.27 (6.9) |

0.62 (15.7) |

2.82 (71.6) |

3.07 (78) |

1.54 (39.1) |

1.29 (32.8) |

0.69 (17.5) |

1.08 (27.4) |

14.1 (358.1) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 4.0 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 5.0 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 51.3 |

| Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration[59] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 3,423 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,875 | −45.2% | |

| 1900 | 646 | −65.5% | |

| 1910 | 1,582 | 144.9% | |

| 1920 | 1,178 | −25.5% | |

| 1930 | 849 | −27.9% | |

| 1940 | 822 | −3.2% | |

| 1950 | 910 | 10.7% | |

| 1960 | 1,283 | 41.0% | |

| 1970 | 1,241 | −3.3% | |

| 1980 | 1,632 | 31.5% | |

| 1990 | 1,220 | −25.2% | |

| 2000 | 1,504 | 23.3% | |

| 2010 | 1,380 | −8.2% | |

| Est. 2015 | 1,312 | [60] | −4.9% |

| source:[61] 2014 Estimate[2] | |||

As of the census[63] of 2000, there were 1,504 people, 694 households, and 419 families residing in the city. The population density was 349.8 per square mile (135.0/km²). There were 839 housing units at an average density of 195.1 per square mile (75.3/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 87.37% White, 0.60% Black or African American, 1.00% Native American, 0.33% Asian, 8.18% from other races, and 2.53% from two or more races. 24.14% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 694 households out of which 20.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.6% were married couples living together, 7.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.5% were non-families. 32.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 15.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.17 and the average family size was 2.73.

In the city the age distribution of the population shows 19.3% under the age of 18, 4.9% from 18 to 24, 19.9% from 25 to 44, 32.5% from 45 to 64, and 23.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 49 years. For every 100 females there were 94.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $26,571, and the median income for a family was $33,750. Males had a median income of $26,923 versus $18,846 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,447. About 13.0% of families and 17.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.6% of those under age 18 and 13.1% of those age 65 or over.[64] In 2010, the total population was 1,380.

Education

Tombstone Unified School District serves Tombstone. The district schools in Tombstone are Walter J. Meyer Elementary School and Tombstone High School.[65][65][66] Residents of the Tombstone school district are within the Cochise Technology District.[67]

Historic properties

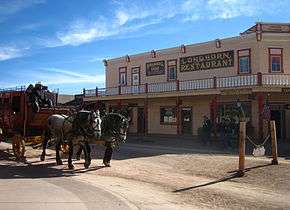

Several properties in Tombstone have been included in the National Register of Historic Places.[68] The following are images of some of these properties:

O.K. Corral frontage on Allen Street

O.K. Corral frontage on Allen Street Schiefflin's Mine

Schiefflin's Mine Schiefflin Hall

Schiefflin Hall Longhorn Restaurant

Longhorn Restaurant Cochise County Courthouse

Cochise County Courthouse- City Hall

Big Nose Kate's Saloon

Big Nose Kate's Saloon Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace

Silver Nugget Bed and Breakfast

Silver Nugget Bed and Breakfast Entrance to Boot Hill Graveyard

Entrance to Boot Hill Graveyard Graves of Billy Clanton, and Frank and Tom McLaury

Graves of Billy Clanton, and Frank and Tom McLaury

In popular culture

Tombstone's western heritage has made the town popular in film, music, and television.

Film

Tombstone has lent its name to many Western movies over the years, including but not limited to Frontier Marshal (1939), Sheriff of Tombstone (1941), My Darling Clementine (1946), Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), Hour of the Gun (1967),Tombstone (1993), and Wyatt Earp (1994).

Music

Bob Dylan wrote a song named "Tombstone Blues" that appears on the album Highway 61 Revisited. Singer/songwriter Carl Perkins wrote a song titled "The Ballad Of Boot Hill" about Billy Clanton's role in the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. It was recorded by Johnny Cash in 1959 and released on his 1965 Columbia Records album Sings the Ballads of the True West. The first line of the Mason Proffit song "Two Hangmen" includes the phrase, "As I rode into Tombstone..." The Brazilian countrycore quartet Matanza published a song named "Tombstone City".

Television

- The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, originally set in Kansas and later in Tombstone, featured Hugh O'Brian as Wyatt Earp from 1955 to 1961.

- The Doctor Who serial The Gunfighters is set in Tombstone.

- From 1957 to 1960, Tombstone was featured in the ABC and later syndicated Western television series Tombstone Territory starring Pat Conway as Sheriff Clay Hollister and Richard Eastham as Harris Claibourne, editor of The Tombstone Epitaph newspaper.

- On October 25, 1968, the Star Trek episode "Spectre of the Gun" premiered. James Kirk, Spock, Montgomery Scott, Leonard McCoy, and Pavel Chekov are forced to fight as the Clanton Gang on the day of the famous shootout at the O.K. Corral.

- Grace Lee Whitney played Nellie Cashman, then a restaurateur in Tombstone, in "The Angel of Tombstone", a 1969 episode of Death Valley Days. In the story line, Cashman and several men travel from Tombstone to Baja California in search of gold found by a Mexican prospector. On reaching the site, Cashman learns how a Catholic mission has been quietly financing its charitable work. Gregg Barton, Tris Coffin, and Joaquin Martinez also guest starred in this episode.[69]

- On October 11, 2006, Tombstone was featured in episode #301 of the Syfy series Ghost Hunters. The TAPS crew led by Jason Hawes and Grant Wilson visit the Birdcage Theatre, which was a popular night spot frequently visited by legends such as Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp. TAPS tries to determine if the place is haunted by spirits of old patrons of the Old West.

- On July 3, 2009, the Birdcage Theatre was once again investigated for paranormal activity by the Travel Channel series Ghost Adventures crew. Ghost hunters Zak Bagans, Nick Groff, and Aaron Goodwin investigate the building while being locked in overnight to find any evidence of its reported ghostly occupants.

- On October 13, 2009, Discovery Channel aired a Tombstone episode of Ghost Lab in which Everyday Paranormal investigated the Birdcage Theater, the Crystal Palace, and Boothill cemetery, as well as looked in a silver mine for a possible source of energy to fuel the large amount of paranormal activity in the city. In the Boothill cemetery, they captured a picture of an alleged "shadow person".

- On November 16, 2011, SyFy featured a landmark in Tombstone on the series Fact or Faked: Paranormal Files, in which the team investigated the Bird Cage Theatre, apparently haunted by a coffin-shaped apparition. The theatre was known for over 26 deaths. SyFy has aired two episodes on two different series investigating the theatre, the other series being Ghost Hunters.

References

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2014-08-31.

- 1 2 "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Tombstone city, Arizona". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ↑ Thompson, George E. (2009). You Live Where?: Interesting and Unusual Facts about where We Live. iUniverse. p. 5.

- ↑ Gallant, Frank K. (2012). A Place Called Peculiar: Stories about Unusual American Place-Names. Courier Dover Publications. p. 15.

- ↑ Beebe, Lucius Morris; Clegg, Charles. The American West: the Pictorial Epic of a Continent.

- ↑ Bishop, William Henry (1888). Mexico, California and Arizona. New York and London: Harper and Brothers. p. 468. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- 1 2 Hendricks, Janice. "Thirty Cents and a Hunch". Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- 1 2 "Silver in the Tombstone Hills". Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ↑ Moore, Richard E. (Winter 1986). "The Silver King: Ed Schieffelin, Prospector". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 87 (4): 367–387. JSTOR 20614087.

- ↑ Horn pp. 26–27

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior National Park Service. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Solon Allis". The Mineralogical Record. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- 1 2 "Engineering and Mining Journal". 29. New York: Scientific Publishing Company. January–June 1880.

- ↑ "Tombstone History - The Grand Hotel". Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ↑ "The O.K. Corral Documents". April 28, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ Linder, Douglas O. (2005). "The Earp-Holliday Trial: An Account".

- ↑ "History of Old Tombstone". Discover Arizona. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ↑ O'Neal, Bill (1979). Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2335-6.

- ↑ "Wyatt Earp's Vendetta Posse". January 29, 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ↑ Weiser, Kathy (June 2010). "Burton Alvord - Lawman Turned Outlaw". LegendsofAmerica.com. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ↑ "Tombstone's Boot Hill". LegendsofAmerica.com. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ↑ Ascarza, William. "Mine Tales: Rich Tombstone mines were a lure for prospectors". Tucson. Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ Trimble, Marshall (1986). Roadside History of Arizona. Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 0-87842-197-1.

- ↑ Walter Noble Burns (September 1, 1999). Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest. UNM Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-8263-2154-1. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ↑ Keane, Melissa; Rogge, A. E. (1992). Gold & Silver Mining in Arizona, 1848-1945. Arizona State Preservation Office. pp. 14–15.

- ↑ "The Story of Edward Schieffelin". March 24, 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Tombstone Mining". Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ↑ Faulk, O. B., (1972) Tombstone. Oxford University Press: New York, pp. 70.

- ↑ Bailey, Lynn R. (2004). Tombstone, Arizona, Too Tough To Die The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Silver Camp; 1878-1990. Tucson, Ariz.: Westernlore Press. ISBN 978-0-87026-115-2. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ↑ Burns, W. N., (1951) Tombstone. Doubleday & Company Inc.: New York, pp. 33-34.

- ↑ "Tombstone, Arizona". The Wild West. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- 1 2 Eppinga, Jane. "Tombstone: Fighting frontier fires". AzCapitalTimes.com. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Losing Gambler". Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Tombstone, Arizona—Boothill". Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ↑ "The History of The Tombstone Epitaph Newspaper". TheTombstoneEpitaph.com. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ↑ WGBH American Experience: Wyatt Earp, Complete Program Transcript. January 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Contention City and Its Mills". Wyatt Earp Explorers. Retrieved May 27, 2011.

- ↑ Rowse, A.L. The Cousin Jacks, The Cornish in America

- ↑ "Tombstone Memories by Harry H. Bishop". Tombstone Epitaph. September 27, 1934. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ↑ "This Month in History", p. 10, Arizona Highways, December 2008.

- 1 2 "A Brief History of Tombstone". Goose Flats Graphics. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Author, Desert (September 30, 2008). "Reverend Endicott Peabody: Tombstone's Quiet Hero". Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ↑ Bishop, William H. (March 1883). "A Traveler in Tombstone". Across Arizona. Harper's Magazine. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Tombstone's Riches". Legends of America. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ↑ Hess, Bill. "Hobby Lobby celebrates enthusiastic opening". Sierra Vista Herald. Wick Communications. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ↑ "O.K. Corral Famous Gunfight Site, Tombstone AZ".

- ↑ "Helldoradodays.com".

- 1 2 "Lady Banks Rose Rosa banksiae". Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Everything is 'Rosey' in Tombstone". Mediterranean Garden Society. Archived from the original on July 2, 2004. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ↑ Arizona: A State Guide. North American Book Dist LLC. January 1, 1940. p. 249.

- ↑ "Tombstone Courthouse State Historic Park". Arizona State Parks. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ↑ Becker, Bill (May 3, 1964). "A RELIC OF THE DAYS WHEN THE WEST WAS WILD". New York Times. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Tombstone, Cochise County". Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- 1 2 "Tombstone District, Tombstone Hills, Cochise Co., Arizona, USA". mindat.org.

- 1 2 Ransome, F.L. (1920). Deposits of Manganese Ore in Arizona. United States Geological Service Bulletin 710. pp. 101–103.

- 1 2 National Weather Service Tucson; NOW Data

- ↑ "TOMBSTONE, AZ" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2001. Retrieved on May 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ Moffatt, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850-1990. Lanham: Scarecrow, 1996, 16.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Population for All Incorporated Places in Arizona" (CSV). 2005 Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. June 21, 2006. Retrieved November 15, 2006.

- 1 2 Home "Walter J. Meyer Elementary School" Check

|url=value (help). Retrieved July 28, 2010. - ↑ "Tombstone High School". Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ↑ Governing Board "Cochise Technology District" Check

|url=value (help). Retrieved July 28, 2010. - ↑ "National Register of Historical Places - ARIZONA (AZ), Maricopa County".

- ↑ "The Angel of Tombstone on Death Valley Days". Internet Movie Data Base. March 8, 1969. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tombstone, Arizona. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tombstone. |

- City of Tombstone official website

- Tombstone Arizona Information and Business Directory

- Tombstone Chamber of Commerce

- Boothill Graveyard in the 1950s

- A tombstone in Boot Hill Cemetery in Tombstone

Additional reading

- Horn, Tom. Life of Tom Horn, Government Scout and Interpreter. (1964, 1973) University of Oklahoma Press. Originally published in 1904 by John C. Coble. ISBN 978-0-8061-1044-8.