Margery Kempe

| Margery Kempe | |

|---|---|

| Born |

1373 Bishop's Lynn (now King's Lynn), Norfolk, England |

| Died | 1438 |

| Occupation | Christian mystic |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | English |

| Notable works | The Book of Margery Kempe |

Margery Kempe (c. 1373–after 1438) was an English Christian mystic, known for dictating The Book of Margery Kempe, a work considered by some to be the first autobiography in the English language. Her book chronicles her domestic tribulations, her extensive pilgrimages to holy sites in Europe and the Holy Land, as well as her mystical conversations with God. She is honoured in the Anglican Communion, but was never made a Roman Catholic saint.

Early life and family

She was born Margery Burnham or Brunham around 1373 in Bishop's Lynn (now King's Lynn), Norfolk, England. Her father, John Brunham, was a merchant in Lynn, mayor of the town and Member of Parliament. His mercantile fortunes may have been negatively affected by downturns in the economy of the 1390s (especially in the wool trade), although he was clearly a successful politician. The first record of her Brunham family is a mention of her grandfather, Ralph de Brunham in 1320 in the Red Register of Lynn. By 1340 he had joined the Parliament of Lynn.[1] Margery’s kinsman, possibly brother, Robert Brunham, became a Member of Parliament for Lynn in 1402 and 1417.[2]

Life

No records remain of any formal education that Margery may have received; and, as an adult, a priest read to her "works of religious devotion" in English, which suggests that she might have been unable to read them herself, although she seems to have learned various texts by heart.[2] Margery appears to have been taught the Pater Noster (the Lord’s Prayer), Ave Maria, the Ten Commandments, and other “virtues, vices, and articles of faith”.[2] At around twenty years of age, Margery married John Kempe, who became a town official in 1394. Margery and John had at least fourteen children, some of whom likely died during infancy. A letter survives from Gdańsk which identifies the name of her eldest son as John and gives a reason for his visit to Lynn in 1431.[3]

Kempe was an orthodox Catholic and, like other medieval mystics, she believed that she was summoned to a “greater intimacy with Christ,” in her case as a result of multiple visions and experiences she had as an adult.[2] After the birth of her first child, Margery went through a period of crisis for nearly eight months.[4] During her illness, Margery claims that she envisioned numerous devils and demons attacking her and commanding her to “forsake her faith, her family, and her friends” and that they even encouraged her to commit suicide.[2] Then, she also claims that she had a vision of Jesus Christ in the form of a man who asked her "Daughter, why have you forsaken me, and I never forsook you?".[2] Margery affirms that she had visitations and conversations with Jesus, Mary, God, and other religious figures and that she had visions of being an active participant during the birth and crucifixion of Christ.[4] These visions and hallucinations physically affected her bodily senses, causing her to hear sounds and smell unknown, strange odours. She also reports hearing a heavenly melody that made her weep and want to live a chaste life. According to Beal, "Margery found other ways to express the intensity of her devotion to God. She prayed for a chaste marriage, went to confession two or three times a day, prayed early and often each day in church, wore a hair shirt, and willingly suffered whatever negative responses her community expressed in response to her extreme forms of devotion".[2] Margery was also known throughout her community for her constant weeping as she begged Christ for mercy and forgiveness.

In Kempe's vision, Christ reassured her that he had forgiven her sins. "He gave her several commands: to call him her love, to stop wearing the hair shirt, to give up eating meat, to take the Eucharist every Sunday, to pray the rosary only until six o'clock, to be still and speak to him in thought…”; He also promised her that He would “give her victory over her enemies, give her the ability to answer all clerks, and that [He] will be with her and never forsake her, and to help her and never be parted from her".[2] Margery did not join a religious order, but carried out "her life of devotion, prayer, and tears in public".[2] Indeed, Margery's visions provoked her public displays of loud wailing, sobbing, and writhing which frightened and annoyed both clergy and laypeople. At one point in her life, she was imprisoned by the clergy and town officials and threatened with the possibility of rape;[4] however, Margery does not record being sexually assaulted.[2] Finally, during the 1420s Margery dictated her Book, known today as The Book of Margery Kempe which illustrates her visions, mystical and religious experiences, as well as her "temptations to lechery, her travels, and her trial for heresy".[5] Margery’s book is commonly considered to be the first autobiography written in the English language.[5]

The Book

Nearly everything that is known of Kempe's life comes from her Book. In the early 1430s, despite her claims to illiteracy, Kempe decided to record her spiritual autobiography. In the preface to the book, she describes how she employed as a scribe an Englishman who had lived in Germany, but he died before the work was completed and what he had written was unintelligible to others. The 1431 letter discovered in Gdańsk lends further credibility to the likelihood that this first scribe was John Kempe, her eldest son.[3] She then persuaded a local priest, who may have been her confessor Robert Springold, to begin rewriting on 23 July 1436, and on 28 April 1438 he started work on an additional section covering the years 1431–4.[3][6]

The narrative of Kempe's Book begins just after her marriage, and relates the experience of her difficult first pregnancy. After describing the demonic torment and Christic apparition that followed, Kempe undertook two domestic businesses: a brewery and a grain mill (both common home-based businesses for medieval women). Both failed after a short period of time. Although she tried to be more devout, she was tempted by sexual pleasures and social jealousy for some years. Eventually turning away from her vocational choices, Kempe dedicated herself completely to the spiritual calling that she felt her earlier vision required. Striving to live a life of commitment to God, Kempe in the summer of 1413 negotiated a chaste marriage with her husband. Although Chapter 15 of The Book of Margery Kempe describes her decision to lead a celibate life, Chapter 21 mentions that she is pregnant once again. It has been speculated that Kempe gives birth to a child, her last, during her pilgrimage; she later relates that she brought a child with her when she returned to England. It is unclear whether the child was conceived before the Kempes began their celibacy, or in a momentary lapse after it.[7]

Sometime around 1413, Kempe visited the female mystic and anchoress Julian of Norwich at her cell in Norwich. According to her own account, Kempe visited Julian and stayed for several days; she was especially eager to obtain Julian's approval for her visions of and conversations with God.[8] The text reports that Julian approved of Kempe's revelations and gave Kempe reassurance that her religiosity was genuine.[9] However, Julian did instruct and caution Kempe to "measure these experiences according to the worship they accrue to God and the profit to her fellow Christians."[10] Julian also confirmed that Kempe's tears are physical evidence of the Holy Spirit in soul.[10] Kempe also received affirmation of her gifts of tears by way of approving comparison to a continental holy woman. In Chapter 62, Kempe describes an encounter with a friar who was relentless in his accusation for her incessant tears. This friar admits to having read of Marie of Oignies and now recognises that Kempe's tears are also a result of similar authentic devotion.[11]

In 1438, the year her book is known to have been completed, a "Margueria Kempe," who may have been Margery Kempe, was admitted to the Trinity Guild of Lynn.[6] It is not known whether this is the same woman, however, and it is unknown when or where after this date Kempe died.

Later influence

The manuscript was copied, probably slightly before 1450, by someone who signed himself Salthows on the bottom portion of the final page, and contains annotations by four hands. The first page of the manuscript contains the rubric, "Liber Montis Gracie. This boke is of Mountegrace," and we can be sure that some of the annotations are the work of monks associated with the important Carthusian priory of Mount Grace in Yorkshire. Although the four readers largely concerned themselves with correcting mistakes or emending the manuscript for clarity, there are also remarks about the Book's substance and some images which reflect Kempe's themes and images.[12]

Kempe's book was essentially lost for centuries, being known only from excerpts published by Wynkyn de Worde in around 1501, and by Henry Pepwell in 1521. However, in 1934 a manuscript (now British Library MS Additional 61823, the only surviving manuscript of Kempe's Book) was found by Hope Emily Allen in the private library of the Butler-Bowdon family.[6] It has since been reprinted and translated in numerous editions.

Kempe's significance

Part of Margery Kempe's significance lies in the autobiographical nature of her book; it is the best insight available of a female, middle class experience in the Middle Ages. Kempe is unusual when compared to contemporaneous holy women, such as Julian of Norwich, because she was a laywoman. Although Kempe has sometimes been depicted as an "oddity" or a "madwoman," recent scholarship on vernacular theologies and popular practices of piety suggest she was not as odd as she might appear. Her Book is revealed as a carefully constructed spiritual and social commentary. Some have suggested that her book is written as fiction and a form of artistry, implying that she intentionally "attempts to create a social reality and to examine that reality in relation to a single individual." By focusing on a single person's experience, Staley suggests, Margery is able to explore the aspects of the society in which she lived in a realistic way. The suggestion that Kempe wrote her book as a work of fiction is supported by the fact that she regards herself as "this creature" throughout the text, dissociating her from her work.[13] Although this is considered by some to be the first autobiography in the English language, there is also evidence that Kempe may have written her book not entirely about herself or to precisely document her personal experiences, but as a work which explores the experience of one person and which sheds light on life in an English Christian society.

Her autobiography begins with "the onset of her spiritual quest, her recovery from the ghostly aftermath of her first child-bearing" (Swanson, 2003, p. 142). There is no firm evidence that Margery Kempe could read or write, but Leyser notes how religious culture was informed by texts. She had such works read to her as the Incendium Amoris by Richard Rolle; Walter Hilton has been cited as another possible influence on Kempe. Among other books that Kempe had read to her were, repeatedly, the Revelationes of Bridget of Sweden and her pilgrimages were related to those of that married saint, who had had eight children.

Kempe and her Book are significant because they express the tension in late medieval England between institutional orthodoxy and increasingly public modes of religious dissent, especially those of the Lollards.[14] Throughout her spiritual career, Kempe was challenged by both church and civil authorities on her adherence to the teachings of the institutional Church. The Bishop of Lincoln and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Arundel, were involved in trials of her allegedly teaching and preaching on scripture and faith in public, and wearing white clothes (interpreted as hypocrisy on the part of a married woman). Kempe proved her orthodoxy in each case. In his efforts to suppress heresy, Arundel had enacted laws that forbade allowing women to preach.

In the 15th century, a pamphlet was published which represented Kempe as an anchoress, and which stripped from her "Book" any potential heterodoxical thought and dissenting behaviour. Because of this, later scholars believed that she was a vowed religious holy woman like Julian of Norwich. They were surprised to encounter the psychologically and spiritually complex woman revealed in the original text of the "Book."

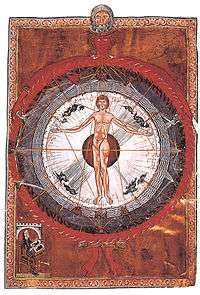

Mysticism

During the fourteenth century, the task of interpreting the Bible and God through the written word was restricted to men, specifically ordained priests; to interpret God through the senses and the body became the domain of women, primarily women mystics, especially in the late Middle Ages.[15] Mystics directly experienced God in three classical ways: first, bodily visions, meaning to be aware with one's senses—sight, sound, or others; second, ghostly visions, such as spiritual visions and sayings directly imparted to the soul; and lastly, intellectual enlightenment, where her mind came into a new understanding of God.[16]

Pilgrimage

Kempe was motivated to make a pilgrimage by hearing or reading the English translation of Bridget of Sweden's Revelations. This work promotes the purchase of indulgences at holy sites; these were pieces of paper representing the pardoning by the Church of purgatorial time otherwise owed after death due to sins. Margery Kempe went on many pilgrimages and has been known to have purchased indulgences for friends, enemies, the souls trapped in Purgatory and herself.[17]

In 1413, soon after her father's death, Margery left her husband to take a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.[18] During the winter, she spent thirteen weeks in Venice[18] but she talks little about her observations of Venice in her book.[18] At the time Venice was at "the height of its medieval splendor, rich in commerce and holy relics."[18] From Venice, Kempe travelled to Jerusalem via Ramlah.[18]

Kempe's voyage from Venice to Jerusalem is not a large part of her story overall. It is thought that she passed through Jaffa, which was the usual port for people who were heading inland.[18] One vivid detail that she recalls was her riding on a donkey when she saw Jerusalem for the first time, probably from Nabi Samwil,[19] and that she nearly fell off of the donkey because she was in such shock from the vision in front of her.[18] During her pilgrimage Kempe visited places that she saw to be holy. She was in Jerusalem for three weeks and went to Bethlehem where Christ was born.[18] She visited Mount Zion, which was where she believed Jesus had washed his disciples' feet. Kempe visited the burial places of Jesus, his mother Mary and the cross itself.[18] Finally, she went to the River Jordan and Mount Quarentyne, which was where they believed Jesus had fasted for forty days and Bethany where Martha, Mary and Lazarus had lived.[18]

After she visited the Holy Land, Kempe returned to Italy and stayed in Assisi before going to Rome.[18] Like many other medieval English pilgrims, Kempe resided at the Hospital of Saint Thomas of Canterbury in Rome.[18] During her stay, she visited many churches including San Giovanni in Laterano, Santa Maria Maggiore, Santi Apostoli, San Marcello and St Birgitta's Chapel.[18] She did not leave Rome until Easter 1415.[18]

When Kempe returned to Norwich, she passed through Middelburg (in today's Netherlands).[18] In 1417, she set off again on pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, travelling via Bristol, where she stayed at Henbury with Thomas Peverel, bishop of Worcester. On her return from Spain she visited the shrine of the holy blood at Hailes Abbey, in Gloucestershire, and then went on to Leicester. Kempe recounts several public interrogations during her travels. One followed her arrest by the Mayor of Leicester who accused her, in Latin, of being a "cheap whore, a lying Lollard," and threatened her with prison. After Kempe was able to insist on the right of accusations to be made in English and to defend herself she was briefly cleared, but then brought to trial again by the Abbot, Dean and Mayor, and imprisoned for three weeks.[20] She returned to Lynn some time in 1418.

She visited important sites and religious figures in England, including Philip Repyngdon (the Bishop of Lincoln), Henry Chichele, and Thomas Arundel (both Archbishops of Canterbury). During the 1420s Kempe lived apart from her husband. When he fell ill, however, she returned to Lynn to be his nursemaid. Their son, who lived in Germany, also returned to Lynn with his wife. However, both her son and husband died in 1431.[21] The last section of her book deals with a journey, beginning in April 1433, aiming to travel to Danzig with her daughter-in-law.[22] From Danzig, Kempe visited the Holy Blood of Wilsnack relic. She then travelled to Aachen, and returned to Lynn via Calais, Canterbury and London (where she visited Syon Abbey).

Veneration

Kempe is honoured in the Church of England on 9 November and in the Episcopal Church in the United States of America together with Richard Rolle and Walter Hilton on 28 September.

References

- ↑ Goodman, Anthony. Margery Kempe and Her World.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Beal, Jane. "Margery Kempe." British Writers: Supplement 12. Ed. Jay Parini. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2007. Scribner Writers Series. n.pag. Web. 23 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 Sobecki, Sebastian (2015). ""The writyng of this tretys": Margery Kempe's Son and the Authorship of Her Book". Studies in the Age of Chaucer. 37: 257–83. doi:10.1353/sac.2015.0015.

- 1 2 3 Torn, Alison. "Medieval Mysticism Or Psychosis?." Psychologist 24.10 (2011): 788–790. Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection. Web. 8 October 2013.

- 1 2 Drabble, Margaret. "Margery Kempe." The Oxford Companion to English Literature. 6th ed. New York: Oxford UP, 2000. 552. Print.

- 1 2 3 Felicity Riddy, 'Kempe, Margery (b. c.1373, d. in or after 1438)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2009).

- ↑ Howes, Laura (November 1992). "On the Birth of Margery Kempe's Last Child". Modern Philology. 90 (2): 220–223. doi:10.1086/392057. JSTOR 438753.

- ↑ Julian of Norwich. Revelation of Love. Trans. John Skinner. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. 1996.

- ↑ Hirsh, John C. The Revelations of Margery Kempe: Paramystical Practices in Late Medieval England.Leiden: E. J. Brill. 1989.

- 1 2 Lochrie, Karma. Margery Kempe and Translations of the Flesh. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 1991.

- ↑ Spearing, Elizabeth. Medieval Writings on Female Spirituality. New York: Penguin Books, 2002. pg. 244.

- ↑ Fredell, Joel. “Design and Authorship in the Book of Margery Kempe.” Journal of the Early Book Society, 12 (2009): 1-34.

- ↑ Staley, Lynn. Margery Kempe's Dissenting Fictions. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994. Print.

- ↑ John Arnold (2004). "Margery's Trials: Heresy, Lollardy and Dissent". A Companion to The Book of Margery Kempe. D.S. Brewer. pp. 75–94.

- ↑ Roman, Christopher. Domestic Mysticism in Margery Kempe and Dame Julian on Norwich: The Transformation of Christian Spirituality in the Late Middle Ages. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press. 2005.

- ↑ Julian of Norwich. Revelations of Love. Trans. John Skinner. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. 1996.

- ↑ Webb, Diana. Medieval European Pilgrimage

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Kempe, Margery (c. 1373 – c. 1440 )." British Writers: Supplement 12. Ed. Jay Parini. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2007. 167–183. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 23 October 2013.

- ↑ http://rememberedplaces.wordpress.com/2014/01/21/mount-joy-the-view-from-palestine/

- ↑ Prudence Allen The Concept of Woman: The Early Humanist Reformation, 1250–1500 2006 Page 469 "In one of her first public interrogations, Margery defended herself against the Mayor of Leicester who had arrested her, saying, "You, you're a cheap whore, a lying Lollard, and you have an evil effect on others—so I'm going to have you put in."

- ↑ Phillips, Kim. "Margery Kempe and The Ages of Woman", in A Companion to The Book of Margery Kempe. Ed. John Arnold and Kathleen Lewis. Woodbridge: D.S. Brewer. 2004. 17–34.

- ↑ Phillips, Kim. "Margery Kempe and the ages of Woman." A Companion to The Book of Margery Kempe. Ed. John Arnold and Katherine Lewis. Woodbridge: D.S. Brewer. 2004. 17–34.

Modern Editions

- The Book of Margery Kempe: A Facsimile and Documentary Edition, ed. Joel Fredell. Online edition.

- The Book of Margery Kempe, ed. Lynn Staley. Kalamazoo: MIP, 1996, and online via the University of Rochester.

- The Book of Margery Kempe, trans. Anthony Bale. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- The Book of Margery Kempe, ed. Sanford Brown Meech, with prefatory note by Hope Emily Allen. EETS. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1940.

- The Book of Margery Kempe: A New Translation, Contexts and Criticism, trans. Lynn Staley. New York: Norton, 2001.

Further reading

- Arnold, John and Katherine Lewis (1994). A Companion to the Book of Margery Kempe, Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell and Brewer.

- Bhattacharji, Santha (1997). God Is An Earthquake: The Spirituality of Margery Kempe, London: Darton, Longman and Todd.

- Cooper, Christine (2004). "Miraculous Translation in The Book of Margery Kempe". Studies in Philology. 101 (3): 270–298. doi:10.1353/sip.2004.0012. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Glenn, Cheryl (2001). “Popular Literacy in the Middle Ages: The Book of Margery Kempe.” In Popular Literacy: Studies in Cultural Practices and Poetics, ed. John Trimbur. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Glück, Robert (1994). Margery Kempe, New York/London: High Risk Books/Serpent's Tail. ISBN 185242334X / ISBN 9781852423346

- Leyser, H. (2003). "Women and the word of God", In D. Wood (ed.). Women and Religion in Medieval England. Oxford: Oxbow. pp 32–45. ISBN 1-84217-098-8

- Lochrie, Karma (1991). Margery Kempe and Translations of the Flesh. The University of Pennsylvania Press. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Renevey, Denis (2000). "Margery's Performing Body: the Translation of Late Medieval Discursive Religious Practices". Writing Religious Women: Female Spiritual and Textual Practice in Late Medieval England: 197–216.

- Sobecki, Sebastian (2015). ""The writyng of this tretys": Margery Kempe's Son and the Authorship of Her Book". Studies in the Age of Chaucer. 37: 257–83. doi:10.1353/sac.2015.0015. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- Staley, Lynn (1994). Margery Kempe's Dissenting Fictions. The Pennsylvania State University Press. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Thornton, Martin. Margery Kempe: An Example in the English Pastoral Tradition (1960)

- Watt, Diane (1997). "A Prophet in Her Own Country: Margery Kempe and the Medieval Tradition" in Secretaries of God. Cambridge, UK: D.S. Brewer.

- Watt, Diane (2006). "Faith in the Landscape: Overseas Pilgrimages in the Book of Margery Kempe". In Clare A. Lees and Gillian R. Overing. A Place to Believe In: Locating Medieval Landscapes. Penn State Press.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Margery Kempe |

- British Library MS Add. 61823: The Margery Kempe Manuscript

- Middle English Text of The Book of Margery Kempe

- Mapping Margery Kempe, a site including the full text of her book with explanations

- The Book of Margery Kempe at Google Books

- The Soul a City: Margery and Julian