Master Apartments

| Master Apartments | |

|---|---|

Riverside Drive entrance | |

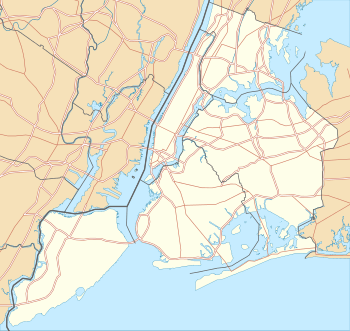

Location within New York City | |

| Former names | Master Building |

| General information | |

| Type | housing cooperative |

| Architectural style | Art Deco |

| Location |

310 Riverside Drive New York, NY, US |

| Coordinates | 40°48′02″N 73°58′17″W / 40.80050°N 73.97126°WCoordinates: 40°48′02″N 73°58′17″W / 40.80050°N 73.97126°W |

| Construction started | 1928-03-24 |

| Opened | 1929-10-17 |

| Cost | $1,925,000 |

| Height | 443 ft (135 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 27 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Harvey Wiley Corbett, Helmle, Corbett & Harrison; and Sugarman & Berger |

|

Master Building | |

| NRHP Reference # | 16000036 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | February 23, 2016 |

| Designated NYCL | December 5, 1989 |

| References | |

| [1] | |

The Master Apartments, officially known as the Master Building, is a landmark[2] 27-story Art Deco skyscraper at 310 Riverside Drive, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, New York City. It sits on the northeast corner of Riverside Drive and West 103rd Street. Built in 1929, it is one of the city's major Art Deco residential buildings and one of its first mixed-use buildings, and is the tallest building on Riverside Drive. It was the first skyscraper in New York City to feature corner windows and the first to employ brick in varying colors for its entire exterior.[3][4] In 2016 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[5]

The Landmarks Preservation Commission report on the building praises its "successful employment of sculptural massing, vertical emphasis, and the minimal, yet elegant, use of surface ornamentation and historically-inspired detailing."[2] Critics have praised the adept handling of the transitions between the base and tower, "as square and chamfered corners established a sprightly syncopation against the more thunderous beat of the central masses."[6]

Naming

Although Master Building is the name that appeared on official documents, the structure had long been known as Master Apartments or The Master. From 1939 onward newspaper advertising used both names constantly.[7] One 1939 ad listed "The Master. Choice 1, 2 room suites, serving pantries, full hotel service, all rooms outside; from $50 month unfurnished; few furnished, $65 month. Popular price restaurant. Home of Riverside Museum. Concerts, lectures, recitals free to residents."[8] The building continued to be called by both names after conversion to a housing cooperative in 1988. At that time it was described as having 335 apartments on 28 floors served by four elevators. Buyers were permitted to finance up to 90% of the purchase price and 28% of the monthly maintenance fee was tax deductible.[9] Since its conversion to a cooperative in 1988, it has continued to be known as either Master Apartments or The Master.

Background

Conception

New York City Parcel Location:

- Borough of Manhattan

- Block 1890

- Lot 40

Building Class:

- Elevator Apartments, Cooperative (D4)

District:

- Community District 107

- City Council District 6

- NYPD 24th Precinct

School:

- PS 145 Bloomingdale School (K-5)

Source:[1]

The skyscraper's first three floors originally held a museum, a school of the fine and performing arts, and an international art center.[4] These three organizations were inspired by Nicholas Roerich and his wife Helena, and were largely funded by a wealthy financier, Louis L. Horch.[10][11] They were the Roerich Museum, the Master Institute of United Arts, and the Corona Mundi International Center of Art.

Nicholas Roerich was a Russian-born artist, explorer, and spiritual leader who spent much of his life in Central Asia. Helena Roerich, also Russian-born, created a spiritual practice called Living Ethics which she and he promoted during the first half of the twentieth century and which survives in a teaching called Agni Yoga. They had married March 8, 1917, when he was 28 and she 20 years old.[12] When the Roeriches and the Horches first met, Nicholas had already amassed a fortune as a foreign exchange expert, beginning on his own in 1905 and, from 1914 onward, in partnership with Curt N. Rosenthal.[13][14] In 1922, when Louis and Nettie Horch met the Roeriches, Horch's net worth was about $1,500,000.[note 1]

Both the building and the Institute take their name primarily from Master Morya, a non-corporeal spiritual leader from whom Helena Roerich received guidance via clairvoyance.[10][16] A secondary source of the name was Roerich himself who was revered as a theosophist master, able to interpret the wisdom of ancient gurus to modern man.[2]

The Master Institute of United Arts came into being in 1920 as the Master School of United Arts. It struggled to survive until, in 1922, Louis Horch financed its transfer from a single-room, all-in-one studio at 314 West 54th Street to a mansion he bought on the site where the Master Building would later be constructed.[13] Horch's wife, Nettie Horch, was a friend of Frances Grant who directed the Master School for the Roeriches. Nettie and Louis were patrons of the arts and ardent believers in art education as an indirect means of promoting harmony among the peoples of the world.[2] They were attracted to the spiritual quest in which the Roeriches were engaged and participated in sessions during which Helena Roerich would receive instructions from Master Morya (or other esoteric beings) and Nicholas Roerich would record them on scrolls of paper that were later transcribed into a series of texts, the Leaves of Morya's Garden.[17][note 2]

The Master Institute aimed to give students a well-rounded education in the arts and also to "open the gates to spiritual enlightenment" through culture.[18] The mansion where it was located also housed the Roerich Museum, containing many of the thousands of paintings Roerich had created, and Corona Mundi, which arranged for exhibitions of paintings by Roerich and international artists.[19][20]

Preparation for construction

In 1925, while the Roeriches were engaged in a long period of travel in Central Asia, Horch began to acquire the lots surrounding the mansion to construct the Master Building.[21] The Roeriches' extensive travels were almost entirely funded by Louis Horch.[note 3] As is common when assembling adjacent lots for a single purpose, he used dummies as purchasers. In doing this he followed a pattern he had established in providing an organizational structure for the Master Institute when he installed the Roeriches and their close associates as nominal shareholders and corporate officers.[13]

In 1928, Horch formed a corporation, Master Building, Inc., in which he was president. The corporation was appointed to plan and construct a skyscraper to replace the mansion in which the museum, institute, and outreach center were located. The architect was Harvey Wiley Corbett, of the architectural firm Helmle, Corbett & Harrison. Plans filed in January 1928 called for a 24-story apartment hotel, topped by a stupa – a Buddhist shrine in the shape of a staggered pyramid with a spire on top. When the building was constructed, plans for the stupa were scrapped in favor of an additional three stories.[2][18][21][note 4] The building was designed to contain 406 rooms. Its cost was given as about $1,700,000 (equivalent to $23,500,000 in 2015).[21][22]

The building was to house a large and a small auditorium, two art libraries, conference rooms, and studios, in addition to three cultural institutions.[23] These would all be located on the first three floors with the remaining stories containing an apartment hotel complying with New York City tenement laws.[note 5] There were to be 390 apartments, most having one bedroom with a few having two or three.[2][24] An article in the New York Times said the planned building was to be "New York's first skyscraper art gallery" and an art critic for the Washington Post called it "a shrine of art with a truly American architectural expression."[25][26]

On June 15, 1928, Horch arranged for the American Bond and Mortgage Company to underwrite a bond of $1,925,000 to cover costs. The bonds were 6% Guaranteed Sinking Fund Gold Bond Certificates held under a trust mortgage with the Chatham Phenix National Bank and Trust Company (predecessor of Manufacturers Hanover Trust Company).[24][27][note 6] Prospective purchasers of the bonds were told that Horch and an associate guaranteed payment of principal and interest personally and that the income from rentals was expected far to exceed expenses, including both interest costs and amounts to be committed to the sinking fund.[27][note 7]

Early years

Construction

Helmle, Corbett & Harrison teamed with another architectural firm, Sugarman & Berger. Henry Sugarman, of the latter organization, advised in the building's design and supervised interior construction work.[2] The cornerstone was laid on March 24, 1929.[29] It has an all-black irregular shape stepped like the building. On it are inscribed the year 1929 and a symbol designed by Roerich consisting of a circle enclosing three dots together with a monogram. The monogram, showing the letter R within the letter M, stands for the Roerich Museum. The circle and the three dots are the symbol of Roerich's Banner of Peace. He once said the circle represents eternity and unity and the dots the triune nature of existence.[30] On another occasion he said the symbol has two meanings: that the circle represents the totality of culture and the dots are art, science, and religion (or philosophy); and that the circle symolizes the endlessness of time and the dots are the past, the present, and the future.[31] The cornerstone contains a 400-year-old casket from the Rajput dynasty of northern India. Made of iron with inlays of gold and silver, the casket contains photographs taken during the Roeriches' expedition to Central Asia.[32] It is also said to contain Jacob's Pillow or the Stone of Scone.[33] Prominent politicians participated in the cornerstone-laying ceremony and among messages read from prominent Americans was a letter from Albert Einstein in which he praised the cultural goals of the building's directors.[34]

Horch expended $2,497,164 for land and construction costs. He used $1,790,500 of the mortgage bond issue, $64,500 of a second mortgage, and made up the rest from a loan he himself made. The completed structure had 233 one-room, 63 two-room, and two three-room apartments as well as a penthouse suite of seven rooms.[13] It had a series of recessions and terraces beginning at the sixteenth story which culminate in a tower. Its steel skeleton was interior, lacking the corner columns that were present in other buildings of the time.[35] It had a brick exterior that was deep purple in its lower stories gradually growing lighter in color until at the top a faint lavender blended into pure white. Harvey Wiley Corbett said the coloration gave the skyscraper a "feeling of growth." He said, "this colored brick exterior, which rises from a low, dark ground to a gleaming, white pinnacle, gives the building a dynamic quality. The play of sunlight on the many hues will make the building a beautiful spectacle of changing colors."[4]

At its opening, press reports emphasized the opportunity for people to rent apartments in a building devoted to the arts and drew attention to the rapid growth of the Institute's cultural ideal of united arts, over seven years, from being housed in a single classroom to moving to a skyscraper. However, many reports did not describe religious factors, with one source saying that "the institution had nothing to do with cults and only with culture."[36]

Financial problems

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 occurred only weeks after the building was completed. At that time more than 80% of the apartments were rented and some 300 students had signed up to take classes at the Institute. However, both rentals and student fees soon dried up and the nonprofit corporation that ran the building was unable to meet its payments. On April 6, 1932, this organization was sued for nonpayment of taxes and sinking fund payments due on the mortgage bonds. At that time it was alleged that the building was being mismanaged, the principal evidence offered being the provision of free living quarters to the Roeriches and their followers.[37] Horch successfully contested the suit partly on a technicality[note 8] and partly by explaining that the 20 rooms occupied rent-free were used by management as partial compensation to employees of the corporation.[13][38] Representatives of the bond holders had argued that the parts of the building that did not produce rental income—that is the museum, institute, and other cultural spaces—should be converted to apartments but Horch successfully countered that the museum et al. were an asset that generated a substantial tax exemption and that, in normal times, they led to higher rental rates from the existing apartments than would comparable apartments. He also pointed out that the demanded conversion would be expensive (about $100,000). In June 1932, the foreclosure case ended with Horch being named one of two receivers tasked with clearing the building's debts.[13]

In 1934, Horch arranged to have Master Institute of United Arts, Inc., the educational corporation he had created in 1923, take over responsibility for the building from the organization he had previously used to run it.[13][note 9] The organization that had previously run the building was called Roerich Museum, Inc. Roerich Museum, Inc. is now the organization that operates the Nicholas Roerich Museum at 319 West 107th Street.[note 10] He did this because the Institute was free of debt and, due to its status as an educational organization, was tax-exempt.[13]

In 1935, the receivership ended and control over the Master Building and the cultural organizations it contained was turned over to the Master Institute of United Arts, Inc. with Horch as its president.[39] At this time Horch arranged for the Institute to give a five-year mortgage for $1,674,800 to the entity that managed the building (now organized as the Riverside Drive & 103d Street Corporation) at five and one-half percent interest.[40]

Horch, who had remained a devoted follower of the Roeriches since his acceptance of their spiritual quest as his own in 1923, started to fall out with them for unclear reasons. The Roeriches maintained that Horch's motives were base: through guile and deception they said he had taken control of the Master Building, closed the cultural institutions it contained, and severed them and their associated from everything connected with the building and its contents. Horch countered that the Roeriches had improperly attempted to countermand his decisions as building owner and director of the cultural organizations it contained. He said they had shown bad faith when they asserted that they alone could receive and interpret the commands of the supreme being whom they all worshiped. On June 8, 1935, he wrote Helena Roerich to say he feared that the Roeriches had lost confidence in himself and his wife Nettie. Then, on July 13, 1935, Nettie wrote Helena of her and Horch's "fourteen years of complete devotion in heart and in deed" and of their enduring "loyalty and selfless sacrifice" over that period. She reaffirmed their "flaming devotion" which they continued to hold in their hearts. And she said the Roeriches' attempt to exert unilateral control over their affairs had caused them to "contemplate, review and think of matters in a new light."[13] These letters explain actions that Horch took on June 5, 1936, to sever relations between the Institute and the other cultural organizations housed at the Master Building and discharge all their employees. The employees who occupied rent-free apartments were told to vacate immediately.[13]

In February 1936, the Roeriches and their associates had attempted to obtain an injunction to prevent these actions.[41] When the attempt failed, they sued Horch to regain what they believed to be their rightful authority to participate in the operation of the building and its component organizations. This case was settled on February 9, 1938, in favor of Horch. George Frankenthaler, the referee who decided the case, found that the Roeriches never possessed the authority they claimed. Horch alone administered the corporation that had the building constructed, ran the organizations that it housed, and obtained all the needed financing. In addition, he donated more than a million dollars of his own, while the Roeriches and their associates had contributed no money at all. Regarding allegations of deception, he found Horch to be the more creditable witness.[13][note 11]

Riverside Museum

Not long afterwards, Horch closed the Roerich Museum and, in the Roerich Museum's former space, established the Riverside Museum. He became president of the new museum and appointed Vernon C. Porter as its director. Open to the public free of charge, the new museum was devoted mainly to exhibitions of contemporary art by American artists.[42][note 12] At its opening in on June 4, 1938, the museum showed modern American paintings and work by native Americans as well as Tibetan art objects that Roerich had given to Horch. The American artists included Stuart Davis, Bernard Karfiol, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Jack Levine, Marsden Hartley, George Luks, John Sloan, Philip Evergood, Reginald Marsh, Charles Burchfield, and Rockwell Kent.[44]

In 1939 the museum began hosting the annual exhibitions of American Abstract Artists, a group devoted to expanding appreciation of non-objective art that had been formed in 1936. The show included more than 300 oils, watercolors, pastels, collages, drawings, constructions, and sculpture.[45] That year it also began hosting exhibitions held by the New York Society of Women Artists, a group that had been founded in 1926 to promote the work of avant garde women artists.[46] Other 1939 shows included contemporary works by artists from Poland,[note 13] documentary photographs of child laborers by Lewis Hine, an international exhibition of works by women artists, and a large display of Pan-American art.[47][48] Over the next few decades the museum would specialize in exhibitions by members of artists' groups. In addition to the two already named, these included the Silvermine Guild of Artists (a Connecticut summer art colony), the Manhattan Camera Club, the Photo-Engravers' Art Society, the Brooklyn Society of Artists, the Artists Equity Group, and USCO (a collective from the Woodstock, New York, art colony).[note 14] The museum was organized as a unit of the Master Institute of United Arts. As it had previously done, the institute gave art classes, provided studio space, and sponsored lectures, concerts, poetry readings, art clinics, and other cultural events.

Porter served as the museum's director through the 1940s.[49] He was succeeded by Nettie Horch, who had been in charge of the Institute's cultural events since the building opened.[50][51] She was assisted by her daughter, Oriole, who took over direction of the museum and cultural events in the late 1960s.[52][53]

Role of Nettie Horch

In addition to running the museum, Nettie had a large role in running the Master Building as a whole; however, the exact division of responsibilities between Nettie and her husband is unclear. She was secretary of the corporation, although this may have been a nominal position as Louis and his lawyer prepared most of the corporation's correspondence and its filings. She also probably helped her husband decide to provide more than one million dollars toward achieving the Roeriches' spiritual and cultural ambitions. She met with the Roeriches and their other supporters in making plans for the Roerich Museum, Master Institute, Corona Mundi, and the other organizations housed in the Master Building. She was active as president of the Roerich Society and, after its demise, directed the Riverside Museum for many years.[13][50][51][54][note 15]

Later years

Neighborhood decline

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Manhattan Valley neighborhood (then known as Bloomingdale), where the Master Building is located, saw its culturally-oriented middle class renters depart, many of them, it was said, opting to buy houses in the suburban New York metropolitan area. As a consequence, the museum and cultural center lost their audience and in 1971 they were forced to close.[note 16] Their holdings were donated to Brandeis University and cultural initiatives such as the Master Institute Chorus, founded in 1960, either folded, or, as in the case of the chorus, became affiliated with other organizations, such as the New Amsterdam Singers.[56][57][58] The Horches' daughter, Oriole, became advisory consultant for the collection at Brandeis.[59] The building's auditorium continued to present concerts, plays, readings, and lectures in the 1940s and into the 1950s. From 1961 through 1978 the Equity Library Theater leased it for productions showcasing the talents of New York actors.[2][60][61]

Bloomingdale went into decline in the late 20th century, as did the rest of the city. During the white flight of the 1950s, as middle-class residents left for the suburbs, buildings were allowed to fall into disrepair and were divided into small units for new low-rent tenants, many of them originally from Puerto Rico. The 1965 completion of the Frederick Douglass Houses, a high-rise housing project, greatly increased the density of low-income renters without providing much in the way of amenities (food shops, clubs, restaurants, and open space) for them to use.[62] The crime rate increased dramatically, along with drug use and poverty.[63] By 1960, the Bloomingdale neighborhood had the highest juvenile delinquency rate in Manhattan and the second highest number of welfare cases per 1,000 residents.[64] New investment in the area in the 1980s was followed by wavering property prices in the late 1980s and early 1990s, combined with the rise of crack use and dealers in the area, which gave Manhattan Valley the reputation as one of the easiest places in the city to get drugs.[65]

As chair of Bloomington Conservation Project, Horch and the Master Institute of United Arts led an effort to improve deteriorated housing by converting single-family brownstone buildings into rent-subsidized apartments.[66][67][68] Efforts like those of this project ameliorated conditions to some extent, but the Bloomingdale area did not return to prosperity until the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the city as a whole experienced an economic rebound.[69][note 17] As high-paying white-collar employment in financial institutions and other service industries replaced long-departed blue-collar jobs in the industrial sector, real estate speculators found that they could profit from new condos and co-ops either by replacing old buildings or by renovating them.[70][71]

Master Apartments co-op and renovations

In 1958, Louis Horch made his son Frank manager of the building, which continued until Frank was murdered during a 1975 robbery.[72] In 1970–71, Louis transferred partial ownership of the building to Frank and Oriole.[73][74] In 1971 Louis and Nettie Horch moved to Florida, when he was 83 years old and she was 76.[75]

Following the death of Louis in 1979, the Horch family sold the Master Building to a real estate investor, Sol Goldman, who was then the city's largest private landlord.[73][76] Goldman continued to operate the building as rental apartments until 1982 when he formed a company, Manhattan Master Apartment Associates, to convert it to a housing co-operative. The conversion was completed in 1988 when that company transferred control to a new organization, Master Apartments, Inc.[73]

After renovations were finished in 2005, the number of two- and three-bedroom units was increased dramatically, due to the combination of the building's original studio apartments. The larger layouts attracted more families to the cooperative community. In recent years the lobby has been restored, hallways remodeled, and amenities increased, including larger storage areas, a bike room, and an improved laundry facility. The building is now said to be luxurious as measured both by residents' quality of living and by the purchase prices they pay.[77]

See also

- List of buildings, sites, and monuments in New York City

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 59th to 110th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan above 59th to 110th Streets

Notes

- ↑ Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department.[15]

- ↑ Entry number 46, which follows, appears to encourage the construction of a building, such as the Master Building, as an educational center for spiritual enlightenment:

Learn to approach Our Heights pure of heart. Our Ray will shine upon you and exalt your daily life. You carry stones for the raising of My new Temple. Teach others My Word, and wisdom will flourish; And a new Temple will be raised. Do not regard Me as a magician, yet can I lead you upward upon the ladder of Beauty beheld only in dreams. Wafting to you the fragrance from the mountains of Tibet, We bring the message of a new religion of the pure spirit to humanity. It is coming; and you, united here in search of light, bear the precious stone. To you is revealed the miracle of creating harmony in life. It will reveal to the world a new Teaching.

— Leaves of Morya's Garden (self published, New York, 1923) - ↑ ROERICH v. HELVERING No. 7578. 115 F.2d 39 (1940), Commissioner of Internal Revenue. United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. Decided September 3, 1940.

- ↑ The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission report on the building states that the building is 29 stories high. The web site of Master Apartment, Inc. gives 28. However, all news accounts state that it has only 27 stories.

- ↑ Apartment hotels were not subject to tenement-law height restrictions. They provided some minimal amenities of hotels such as the availability of maids and an on-site restaurant. They also provided small kitchens, called "pantries," in each unit.

- ↑ The tombstone ad for the issue said it consisted of a 6% first mortgage of 12-year sinking fund bond certificates denoted "Series A." They were dated June 15, 1928, and were to mature on June 15, 1940. The certificates were secured by a first mortgage of $2,075,000 of which $150,000 was designated as Series "B" and was subordinate to the bond issue. The corporate trustee was Chatham Phenix National Bank and Trust Co.[28]

- ↑ The associate listed with Horch as guarantor, Maurice Lictmann, had little net worth and Horch himself was actually the only guarantor. The tombstone ad said the property on completion had been appraised at $2,900,000 and land valued at $610,000. The ad also said "The first three floors have been leased at an annual rental of $65,000 for 21 years. Net income estimated at $249,620 or over twice the heaviest annual interest requirements on this issue."

- ↑ The suit was mistakenly taken in a Bronx court rather than one in Manhattan.

- ↑ Master Institute of United Arts, Inc. had as its (nominally participating) officers the same people who were officers of the museum.

- ↑ Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, First Department. ROERICH v. HORCH. 254 App. Div. 663 (N.Y. App. Div. 1938). NICHOLAS ROERICH, HELENA ROERICH, MAURICE M. LICHTMANN, SINA LICHTMANN and FRANCES R. GRANT, Appellants, v. LOUIS L. HORCH, NETTIE S. HORCH, and MASTER INSTITUTE OF UNITED ARTS, INC., Respondents. April 22, 1938.

- ↑ George Frankenthaler (1886–1968) was a justice of the Supreme Court of New York State. He was the brother of justice Alfred Frankenthaler of the same court (and thus uncle of the abstract expressionist painter Helen Frankenthaler.

- ↑ The Roerich Museum reopened in 1949 with a small portion of the works by him that had been displayed in the Master Building. The new Nicholas Roerich Museum is located at 319 West 107th Street, a few blocks uptown.[43]

- ↑ These are said to be the last group of paintings to leave Poland before it was devastated by Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia.

- ↑ This list comes from contemporary reports in New York newspapers.

- ↑ From 1937 to 1954 Nettie Horch was also fine arts chairman of the National Council of Women of the United States.[55]

- ↑ See also: History of New York City (1946–77)

- ↑ See also: History of New York City (1978–present) and New York City#Modern history.

References

- 1 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Betsy Bradley; ed. by Jay Shockley and Elisa Urbanelli (1989-12-05). "NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission Report on the Master Apartments" (PDF). Master Building, 310-312 Riverside Drive, Borough of Mahnattan. New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved 2015-01-06. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Christopher Gray (1995-01-29). "A Restoration for the Home of a Russian Philosopher: Riverside Drive Co-op Once Housed Museum of Nicholas Roerich". New York Times. p. R7.

- 1 2 3 "First Skyscraper Entirely of Brick; Master Building at Riverside Drive and 103d St. will Have Unique Facade; Of Varying Colors". New York Evening Post. 1929-04-13. p. 13.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places listings for March 4, 2016". U.S. National Park Service. March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Master Building Review". CityRealy.com. Retrieved 2015-01-26.

quoting: New York 1930, Architecture and Urbanism Between The Two World Wars by Robert A. M. Stern, Gregory Gilmartin and Thomas Mellins (Rizzoli International Publications, 1987)

- ↑ "Shoots Wife, Child and Kills Himself". New York Times. 1939-12-29. p. 16.

- ↑ "Classified Ads". New York Times. 1939-01-24. p. 18.

- ↑ "MASTER BUILDING at 310 Riverside Drive in Upper West Side: Sales, Rentals, Floorplans". StreetEasy. Retrieved 2015-01-15.

- 1 2 "Secondat: Master Institute". Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- ↑ "Louis L. Horch, 90, Founder of Museum; Set Up Master Institute of Arts—Foreign-Exchange Expert". New York Times. 1979-04-16. p. D13.

- ↑ "Person Details for Nettie S Horch, "United States Social Security Death Index"". FamilySearch.org. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Roerich v. Horch, May 25, 1938. Appelate Division, First Department, Supreme Court, State of New York. pp. passim.

- ↑ "Financial Notes". Wall Street Journal. 1914-11-03. p. 8.

- ↑ ROERICH v. HORCH. 254 App. Div. 663 (N.Y. App. Div. 1938). NICHOLAS ROERICH, HELENA ROERICH, MAURICE M. LICHTMANN, SINA LICHTMANN and FRANCES R. GRANT, Appellants, v. LOUIS L. HORCH, NETTIE S. HORCH, and MASTER INSTITUTE OF UNITED ARTS, INC., Respondents. April 22, 1938.

- ↑ Alexandre Andreyev (8 May 2014). The Myth of the Masters Revived: The Occult Lives of Nikolai and Elena Roerich. BRILL. p. 329. ISBN 978-90-04-27043-5.

The 29-story Skyscraper Master—named so after the Roerich's Invisible Teacher, Master Morya,—was designed and developed by Harvey Wiley Corbett of the firm of Helmle, Corbett & Harrison in association with Sugarman & Berger.

- ↑ Elena Ivanovna Roerich (1923). Leaves of Morya's Garden. Self published, New York.

- 1 2 Jacqueline Decter (1989). Nicholas Roerich: The Life and Art of a Russian Master. Inner Traditions Bear and Company, London.

- ↑ "Inventory to the Papers of Frances R. Grant". Rutgers University Archives. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- ↑ "Next Come The Water Colorists". Globe and Sun, New York. 1923-12-22. p. 5.

- 1 2 3 "Art Centre for Drive; One-quarter of Tall Hotel Will Be Occupied by Institute". New York Times. 1928-01-17. p. 51.

- ↑ "Hotel and Apartment Hotel Plans Filed in Manhattan During 1928". New York Times. 1929-01-13. p. 162.

- ↑ "Skyscraper Planned for Three Art Units". New York Times. 1928-07-13. p. 11.

- 1 2 "$1,925,000 Loan on Art Skyscraper; American Bond and Mortgage Company Finances Roerich Museum on Riverside Drive". New York Evening Post. 1928-07-14. p. 12.

- ↑ "Art Rears a Skyscraper". New York Times. 1929-06-23. p. X10.

- ↑ Ada Rainey (1928-08-19). "Precedence Given Young U.S. Artists: Skyscraper Art Museum in New York". Washington Post. p. S9.

- 1 2 "Tombstone Ad; New Issue; $1,925,000; Riverside Drive & 103d St. Bldg.". Buffalo Courier Express. 1928-07-18. p. 13.

- ↑ Tombstone ad, Buffalo Courier Express, July 18, 1928, p. 13)

- ↑ "Roerich Ceremony Tomorrow". New York Times. 1929-03-23. p. 11.

- ↑ "Roerich Museum Lays Cornerstone: Messages From All Over World Read at Exercises at the Riverside Skyscraper". New York Times. 1929-03-23. p. 31.

- ↑ "Master, 310 Riverside Drive". condopedia.com. Retrieved 2015-01-27.

- ↑ "Einstein Is Found Hiding on Birthday". New York Times. 1929-03-15. p. 3.

- ↑ "West Side Hotel Has Art Museum: Riverside Drive Reveals Modernistic Architecture in Master Building". New York Times. 1929-09-15. p. RE1.

- ↑ Helen Appleton Read (1929-10-13). "Art as an Aid to Peace; Roerich Museum, Opening in Manhattan on Thursday Evening, First to Adopt Skyscraper Type". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 2B.

- ↑ "Roerich Receivership Is Upheld by Court". New York Times. 1932-05-12. p. 22.

- ↑ "Named Roerich Receiver: Horch, Donor of $1,000,000, Will Aid Museum in Foreclosure Case". New York Times. 1932-05-12. p. 26.

- ↑ "Roerich Museum Ends Receivership". New York Times. 1935-02-24. p. N1.

- ↑ "Recorded Mortgages". New York Sun. 1935-11-26. p. 39.

- ↑ "Injunction denied to Roerich Group: Court Holds Ownership of the Museum Stock Must Be Decided by Trial". New York Times. 1936-02-12. p. 19.

- ↑ "Roerich Museum to Change Identity: Closed Until June 4, When It Will Reopen as Riverside Museum". New York Times. 1938-05-14. p. 19.

- ↑ Christopher Gray (1995-01-29). "Streetscapes/The Master Apartments; A Restoration for the Home of a Russian Philosopher". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ↑ "New Museum Holds Display; Riverside Institution Shows American Art; Is First of Series Planned; Is Project of Broad Cultural and Educational Scope". New York Sun. 1938-06-04. p. 7.

- ↑ Edward Alden Jewell (1939-03-08). "Abstract Artists Show Their Work; Third Annual Exhibition Opens". New York Times. p. 24.

- ↑ Edward Alden Jewell (1939-03-25). "Whitney Museum Makes Fair Plans". New York Times. p. 13.

- ↑ "Late Polish Art In Exhibit Here". New York Times. 1939-10-15. p. 54.

- ↑ Howard Devree (1939-10-18). "Women's Art Work in 11 Nations Seen". New York Times. p. 34.

- ↑ "Paintings on Display By Valley Artists". Putnam County Courier, Carmel, N.Y. 1953-07-09. p. 14.

- 1 2 Martha Dreiblatt (1933-06-19). "Directs Culture; Heading 64 Societies of "Art and Culture," Wife of Museum President is Busy and Happy". New York Evening Post. p. 8.

- 1 2 "City Salutes Museum; Riverside Institution and Its Head Cited for Art Service". New York Times. 1957-10-21. p. 34.

- ↑ Julie Besonen (1968-09-10). "Tibetan Art, Wrapped in Supernatural and Occult, Is Back in Vogue". New York Times. p. 49.

- ↑ "Oriole Horch is Married: Sarah Lawrence Senior Bride Here of Peter Farb". New York Times. 1953-02-28. p. 15.

- ↑ "Founder of Museum: Set Up Master Institute of United Arts". New York Times. 1979-04-16. p. D13.

- ↑ "Nettie S. Horch, An Arts Patron, Is Dead at 94", New York Times, May 1, 1991.

- ↑ Sanka Knox (1971-06-17). "Brandeis Merger Is Set For Riverside Museum". New York Times. p. 48.

- ↑ "If I Couldn't Conduct...: Karl Boehm". New York Times. 1972-03-26. p. D15.

- ↑ "Master Institute Chorus". New York Times. 1960-09-11. p. X18.

- ↑ Joseph Berger (1971-06-17). "Brandeis Merger Is Set For Riverside Museum". New York Times. p. B1.

- ↑ Andrew L. Yarrow (1988-02-07). "Equity Library Theater Gives Itself a Party". New York Times. p. 69.

- ↑ Eric Pace (1978-11-30). "Equity Library Theater Seeks Home: Fears on Fire and Security 344 Rental Apartments". New York Times. p. C16.

- ↑ "West 100th St.: Prosperity Ends and Crime Begins". New York Times. 1986-07-22. p. A24.

- ↑ George Goodman Jr. (1972-11-26). "West 100th St.: Prosperity Ends and Crime Begins". New York Times. p. D84.

- ↑ "Where The Need Is Greatest". New York Times. 1963-10-27. p. 405.

- ↑ Nieves, Evelyn (December 25, 1990). "Manhattan Valley's Long Awaited Boom Ends Up Just a Fizzle". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ↑ "West Side Begins Anti-Slum Work". New York Times. 1959-09-30. p. 22.

- ↑ "Brownstone Project To Be Dedicated Here". New York Times. 1962-05-13. p. 35.

- ↑ "West Side Begins Anti-Slum Work". New York Times. 1979-01-14. p. SM4.

- ↑ Haller, Vera (January 6, 2008). "City Living: Manhattan Valley". Newsday.

- ↑ Philip s. Gutis (1986-03-09). "96th St. Barrier Falls As section Develops a Cachet and Vitality". New York Times. p. R1.

- ↑ Joseph Berger (1987-09-11). "Hispanic Life Dims in Manhattan Valley: Hispanic Way of Life Fading in Manhattan Valley". New York Times. p. B1.

- ↑ "Police on West Side Seek Killer of Arts-Center Head". New York Times. 1975-02-23. p. 34.

- 1 2 3 "acris, Automated City Register Information System". City of New York, Finance Commission. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

- ↑ Grace Glueck (1991-05-01). "Nettie S. Horch, an Arts Patron, Is Dead at 94". New York Times. p. D25.

- ↑ "Deaths Elsewhere". St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, Florida. 1991-05-02. p. 7B.

- ↑ "Sol Goldman, Major Real-Estate Investor, Dies". New York Times. 1987-10-19.

- ↑ "Master Apartments; 310 Riverside Drive, New York, NY". Master Apartments Inc. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

External links

- Official website

- Master Apartments (Kenneth G. Grant at NewYorkArchitecture.com)

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission Report on Master Apartments

- City Realty Review

- Master Apartments at Emporis.com

- Louis L. and Nettie S. Horch Papers, circa 1920s-1960s Held by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

Images:

Media related to Master Apartments at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Master Apartments at Wikimedia Commons- Master Apartments on NYMetropics.com

- Master Apartments on NewYorkArchitecture.com