Meridiani Planum

|

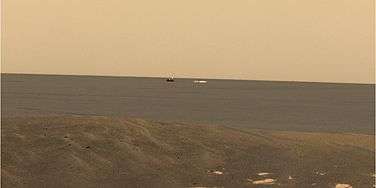

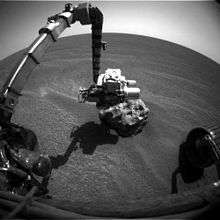

Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity looks southwest across Meridiani Planum; the Rover's discarded backshell and parachute are visible in the distance. | |

| Coordinates | 0°12′N 357°30′E / 0.2°N 357.5°ECoordinates: 0°12′N 357°30′E / 0.2°N 357.5°E |

|---|---|

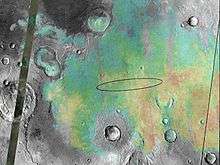

Meridiani Planum is a plain located 2 degrees south of Mars' equator (centered at 0°12′N 357°30′E / 0.2°N 357.5°E), in the westernmost portion of Terra Meridiani. It hosts a rare occurrence of gray crystalline hematite. On Earth, hematite is often formed in hot springs or in standing pools of water; therefore, many scientists believe that the hematite at Meridiani Planum may be indicative of ancient hot springs or that the environment contained liquid water. The hematite is part of a layered sedimentary rock formation about 200 to 800 meters thick. Other features of Meridiani Planum include volcanic basalt and impact craters.

Meridiani Planum was chosen as the landing site for the spacecraft landings of MER-B and the ExoMars EDM, the flat terrain, low-elevation, and relative lack of rocks and craters have made it favored location.[1] This region also contains Challenger Memorial Station.[2]

Mars rover Opportunity, a summary

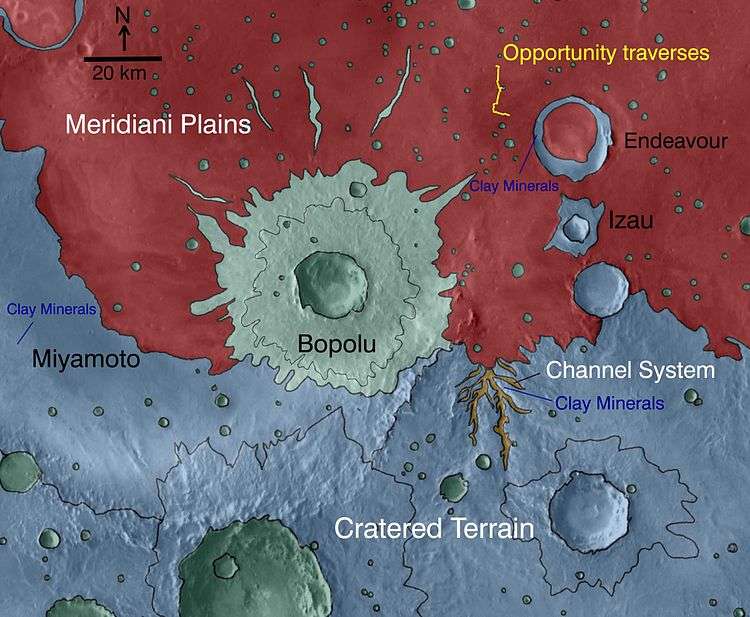

In 2004, Meridiani Planum was the landing site for the second of NASA's two Mars Exploration Rovers, named Opportunity. It had also been the target landing site for Mars Surveyor 2001 Lander, which was cancelled after the failures of the Mars Climate Orbiter and Mars Polar Lander missions.

Results from Opportunity indicate that its landing site was once saturated for a long period of time with liquid water, possibly of high salinity and acidity. Features that suggest this include cross-bedded sediments, the presence of many small spherical pebbles that appear to be concretions, vugs inside rocks, and the presence of large amounts of magnesium sulfate and other sulfate-rich minerals such as jarosite.

Opportunity Rover's rocks and minerals discoveries at Meridiani Planum

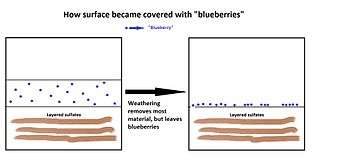

Opportunity Rover found that the soil at Meridiani Planum was very similar to the soil at Gusev Crater and Ares Vallis; however in many places at Meridiani the soil was covered with round, hard, gray spherules that were named “blueberries.”[3] These blueberries were found to be composed almost entirely of the mineral hematite. It was decided that the spectra signal spotted from orbit by Mars Odyssey was produced by these spherules. After further study it was decided that the blueberries were concretions formed in the ground by water.[4] Over time, these concretions weathered from what was overlying rock, and then became concentrated on the surface as a lag deposit. The concentration of spherules in bedrock could have produced the observed blueberry covering from the weathering of as little as one meter of rock.[5][6] Most of the soil consisted of olivine basalt sands that did not come from the local rocks. The sand may have been transported from somewhere else.[7]

|

Minerals in dust

A Mössbauer spectrum was made of the dust that gathered on Opportunity’s capture magnet. The results suggested that the magnetic component of the dust was titanomagnetite, rather than just plain magnetite, as was once thought. A small amount of olivine was also detected which was interpreted as indicating a long arid period on the planet. On the other hand, a small amount of hematite that was present meant that there may have been liquid water for a short time in the early history of the planet.[8] Because the Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT) found it easy to grind into the bedrock, it is thought that the rocks are much softer than the rocks at Gusev Crater.

Bedrock minerals

Few rocks were visible on the surface where Opportunity landed, but bedrock that was exposed in craters was examined by the suite of instruments on the Rover.[9] Bedrock rocks were found to be sedimentary rocks with a high concentration of sulfur in the form of calcium and magnesium sulfates. Some of the sulfates that may be present in bedrocks are kieserite, sulfate anhydrate, bassanite, hexahydrite, epsomite, and gypsum. Salts, such as halite, bischofite, antarcticite, bloedite, vanthoffite, or gluberite may also be present.[10][11]

The rocks contained the sulfates had a light tone compared to isolated rocks and rocks examined by landers/rovers at other locations on Mars. The spectra of these light toned rocks, containing hydrated sulfates, were similar to spectra taken by the Thermal Emission Spectrometer on board the Mars Global Surveyor. The same spectrum is found over a large area, so it is believed that water once appeared over a wide region, not just in the area explored by Opportunity Rover.[12]

The Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) found rather high levels of phosphorus in the rocks. Similar high levels were found by other rovers at Ares Vallis and Gusev Crater, so it has been hypothesized that the mantle of Mars may be phosphorus-rich.[13] The minerals in the rocks could have originated by acid weathering of basalt. Because the solubility of phosphorus is related to the solubility of uranium, thorium, and rare earth elements, they are all also expected to be enriched in rocks.[14]

When Opportunity Rover traveled to the rim of Endeavour Crater, it soon found a white vein that was later identified as being pure gypsum.[15][16] It was formed when water carrying gypsum in solution deposited the mineral in a crack in the rock. A picture of this vein, called "Homestake" formation, is shown below.

Evidence for water

Examination of Meridiani rocks found strong evidence for past water. The mineral called jarosite which only forms in water was found in all bedrocks. This discovery proved that water once existed in Meridiani Planum[17] In addition, some rocks showed small laminations (layers) with shapes that are only made by gently flowing water.[18] The first such laminations were found in a rock called “The Dells.” Geologists would say that the cross-stratification showed festoon geometry from transport in subaqueous ripples.[19] A picture of cross-stratification, also called cross-bedding, is shown on the left.

Box-shaped holes in some rocks were caused by sulfates forming large crystals, and then when the crystals later dissolved, holes, called vugs, were left behind.[20][21] The concentration of the element bromine in rocks was highly variable probably because it is very soluble. Water may have concentrated it in places before it evaporated. Another mechanism for concentrating highly soluble bromine compounds is frost deposition at night that would form very thin films of water that would concentrate bromine in certain spots.[22]

Rock from impact

One rock, “Bounce Rock,” found sitting on the sandy plains was found to be ejecta from an impact crater. Its chemistry was different than the bedrocks. Containing mostly pyroxene and plagioclase and no olivine, it closely resembled a part, Lithology B, of the shergottite meteorite EETA 79001, a meteorite known to have come from Mars. Bounce rock received its name by being near an airbag bounce mark.[23]

Meteorites

Opportunity Rover found meteorites just sitting on the plains. The first one analyzed with Opportunity’s instruments was called “Heatshield Rock,” as it was found near where Opportunity’s headshield landed. Examination with the Miniature Thermal Emission Spectrometer (Mini-TES), Mossbauer spectrometer, and APXS lead researchers to, classify it as an IAB meteorite. The APXS determined it was composed of 93% iron and 7% nickel. The cobble named “Fig Tree Barberton” is thought to be a stony or stony-iron meteorite (mesosiderite silicate),[24][25] while “Allan Hills,” and “Zhong Shan” may be iron meteorites.

|

Geological history

Observations at the site have led scientists to believe that the area was flooded with water a number of times and was subjected to evaporation and desiccation.[26] In the process sulfates were deposited. After sulfates cemented the sediments, hematite concretions grew by precipitation from groundwater. Some sulfates formed into large crystals which later dissolved to leave vugs. Several lines of evidence point toward an arid climate in the past billion years or so, but a climate supporting water, at least for a time, in the distant past.[27]

Layers

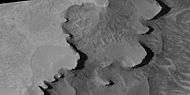

Parts of Meridiani Planum display layered features from orbit. Layers may have been formed with the aid of water, especially ground water.

A detailed discussion of layering with many Martian examples can be found in Sedimentary Geology of Mars.[28]

Close view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program At least one layer is light-toned which may indicated hydrated minerals.

Close view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program At least one layer is light-toned which may indicated hydrated minerals. Close view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Close view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Craters within Meridiani Planum

- Ada Crater

- Airy Crater – 40 kilometre (km) in diameter and about 375 km west-southwest of Opportunity

- Airy-0 – Lies within the Airy crater, and defines the Martian Prime Meridian

- Argo Crater – Visited by Opportunity

- Beagle Crater – Visited by Opportunity

- Beer Crater

- Bopolu Crater

- Crommelin Crater

- Eagle Crater – Landing site of Opportunity and 30 metre diameter

- Emma Dean Crater – Visited by Opportunity

- Endeavour Crater – Visited by Opportunity

- Endurance Crater – Visited by Opportunity

- Erebus Crater – Visited by Opportunity

- Firsoff Crater - Candidate landing site for 2020 rover mission

- Iazu Crater

- Mädler Crater

- Santa Maria Crater - Visited by Opportunity

- Victoria Crater – Visited by Opportunity and 750 metre diameter

- Vostok Crater – Visited by Opportunity

See also

References

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Yen, A., et al. 2005. An integrated view of the chemistry and mineralogy of martian soils. Nature. 435.: 49-54.

- ↑ Bell, J (ed.) The Martian Surface. 2008. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86698-9

- ↑ Squyres, S. et al. 2004. The Opportunity Rover’s Athena Science Investigation at Meridiani Planum, Mars. Science: 1698-1703.

- ↑ Soderblom, L., et al. 2004. Soils of Eagle Crater and Meridiani Planum at the Opportunity Rover Landing Site. Science: 306. 1723-1726.

- ↑ Christensen, P., et al. Mineralogy at Meridiani Planum from the Mini-TES Experiment on the Opportunity Rover. Science: 306. 1733-1739.

- ↑ Goetz, W., et al. 2005. Indication of drier periods on Mars from the chemistry and mineralogy of atmospheric dust. Nature: 436.62-65.

- ↑ Bell, J., et al. 2004. Pancam Multispectral Imaging Results from the Opportunity Rover at Meridiani Planum. Science: 306.1703-1708.

- ↑ Christensen, P., et al. 2004 Mineralogy at Meridiani Planum from the Mini-TES Experiment on the Opportunity Rover. Science: 306. 1733-1739.

- ↑ Squyres, S. et al. 2004. In Situ Evidence for an Ancient Aqueous Environment at Meridian Planum, Mars. Science: 306. 1709-1714.

- ↑ Hynek, B. 2004. Implications for hydrologic processes on Mars from extensive bedrock outcrops throughout Terra Meridiani. Nature: 431. 156-159.

- ↑ Dreibus,G. and H. Wanke. 1987. Volatiles on Earth and Marsw: a comparison. Icarus. 71:225-240

- ↑ Rieder, R., et al. 2004. Chemistry of Rocks and Soils at Meridiani Planum from the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer. Science. 306. 1746-1749

- ↑ http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/mer/news/mer20111207.html

- ↑ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/01/120125093619.htm

- ↑ Klingelhofer, G. et al. 2004. Jarosite and Hematite at Meridiani Planum from Opportunity’s Mossbauer Spectrometer. Science: 306. 1740-1745.

- ↑ Herkenhoff, K., et al. 2004. Evidence from Opportunity’s Microscopic Imager for Water on Meridian Planum. Science: 306. 1727-1730

- ↑ Squyres, S. et al. 2004. In Situ Evidence for an Ancient Aqueous Environment at Meridian Planum, Mars. Science: 306. 1709-1714.

- ↑ Herkenhoff, K., et al. 2004. Evidence from Opportunity’s Microscopic Imager for Water on Meridian Planum. Science: 306. 1727-1730

- ↑ Marion, G.M.; Catling, D.C.; Zahnle, K.J.; Claire, M.W. (2010). "Modeling aqueous perchlorate chemistries with applications to Mars". Icarus. 207 (2): 675–685. Bibcode:2010Icar..207..675M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.12.003. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ↑ Yen, A., et al. 2005. An integrated view of the chemistry and mineralogy of martian soils. Nature. 435.: 49-54.

- ↑ Squyres, S. et al. 2004. The Opportunity Rover’s Athena Science Investigation at Meridiani Planum, Mars. Science: 1698-1703.

- ↑ Squyres, S., et al. 2009. Exploration of Victoria Crater by the Mars Rover Opportunity. Science: 1058-1061.

- ↑ Schroder,C., et al. 2008. J. Geophys. Res: 113.

- ↑ Squyres, S. et al. 2004. The Opportunity Rover’s Athena Science Investigation at Meridiani Planum, Mars. Science: 1698-1703.

- ↑ Clark, B. et al. Chemistry and mineralogy of outcrops at Meridiani Planum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 240: 73-94.

- ↑ Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken (eds.). 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meridiani Planum. |

- Google Mars zoomable map – centered on Meridiani Planum

- The sedimentary rocks of Sinus Meridiani: Five key observations from data acquired by the Mars Global Surveyor and Mars Odyssey orbiters

- ESA - Meridiani Planum

.jpg)