Mickey Rooney

| Mickey Rooney | |

|---|---|

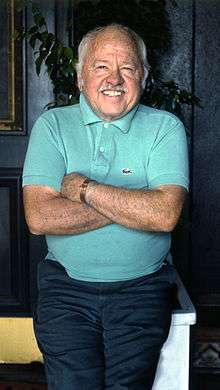

Rooney in 1945 | |

| Born |

Joseph Yule, Jr. September 23, 1920 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

April 6, 2014 (aged 93) Studio City, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Natural causes |

| Resting place | Hollywood Forever Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Education |

Hollywood High School Hollywood Professional School |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1926–2014 |

| Height | 1.57 m (5 ft. 2 in.) |

| Spouse(s) | (see article) |

| Children | 9 |

| Parent(s) |

Joseph Yule (father) Nellie W. Carter (mother) |

| Awards | Juvenile Academy Award, Academy Honorary Award, Emmy, 2 Golden Globes |

| Website |

mickeyrooney |

Mickey Rooney (born Joseph Yule, Jr.; September 23, 1920 – April 6, 2014) was an American actor of film, television, Broadway, radio, and vaudeville. In a career spanning nine decades and continuing until shortly before his death, he appeared in more than 300 films and was one of the last surviving stars of the silent film era.[1]

At the height of a career that was marked by precipitous declines and raging comebacks, Rooney played the role of Andy Hardy in a series of fifteen films in the 1930s and 1940s that epitomized American family values. A versatile performer, he could sing, dance, clown, and play various musical instruments, becoming a celebrated character actor later in his career. Laurence Olivier once said he considered Rooney "the best there has ever been."[2] Clarence Brown, who directed him in two of his earliest dramatic roles, National Velvet and The Human Comedy, said he was "the closest thing to a genius I ever worked with."[3]

Rooney first performed in vaudeville as a child and made his film debut at the age of six. At thirteen he played the role of Puck in the play and later the 1935 film adaptation of A Midsummer Night's Dream. His performance was hailed by critic David Thomson as "one of cinema's most arresting pieces of magic". In 1938, he co-starred with Spencer Tracy in the Academy Award-winning film Boys Town. At nineteen he was the first teenager to be nominated for an Oscar for his leading role in Babes in Arms, and he was awarded a special Academy Juvenile Award in 1939.[4] At the peak of his career between the ages of 15 and 25, he made forty-three films and co-starred alongside Judy Garland, Wallace Beery, Spencer Tracy, and Elizabeth Taylor. He was one of MGM's most consistently successful actors and a favorite of studio head Louis B. Mayer.

Rooney was the top box office attraction from 1939–41,[5] and one of the best-paid actors of that era,[2] but his career never rose to such heights again. Drafted into the Army during World War II, he served nearly two years entertaining over two million troops on stage and radio and was awarded a Bronze Star for performing in combat zones. Returning from the war in 1945, he was too old for juvenile roles but too short to be an adult movie star, and he was not able to obtain acting roles as significant as before. Nevertheless, Rooney was tenacious and he rebounded, his popularity renewed with well-received supporting roles in films such as Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962), It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), and The Black Stallion (1979) for which he was nominated for an Oscar. In the early 1980s, he returned to Broadway in Sugar Babies and again became a celebrated star. Rooney made hundreds of appearances on TV, including dramas, variety programs, and talk shows. During his career, he received four Academy Award nominations and was nominated for five Emmy Awards, winning one.

At his death, Vanity Fair called him "the original Hollywood train wreck."[5] He struggled with alcohol and pill addiction and married eight times, the first time to Ava Gardner. Despite earning millions during his career, he had to file for bankruptcy in 1962 due to mismanagement of his finances. Shortly before his death in 2014 at age 93, he alleged mistreatment by some family members and testified in Congress about what he alleged was physical abuse and exploitation by family members. By the end of his life, his millions in earnings had dwindled to an estate that was valued at only $18,000,[6] he died owing medical bills and back taxes, and contributions were solicited from the public.[7][8]

Early life

Rooney was born Joseph Yule, Jr. on September 23, 1920, in Brooklyn, New York, the only child of vaudevillians Joe Yule (born Ninian Joseph Ewell; 1892–1950), a native of Glasgow, Scotland, and Nellie W. Carter (1897–1966), who was from Kansas City, Missouri. At the time of their son's birth, they were appearing in a Brooklyn production of A Gaiety Girl. Rooney later recounted in his memoirs that he began performing at the age of 17 months as part of his parents' routine, wearing a specially tailored tuxedo.[9] According to another account, he first appeared before audiences at 15 months in his parents' vaudeville act, "singing 'Pal o' My Cradle Days' while sporting a tuxedo and holding a rubber cigar."[10] His mother was a former chorus girl and a burlesque performer.[2] Another account states that Rooney began performing at the age of ten months, then became a regular part of his father's act, and at the age of three became a part of the vaudeville act of comedian Sid Gold.[11]

While Joe Sr. was traveling, Joe Jr. and his mother moved from Brooklyn to Kansas City to live with his aunt. While his mother was reading the entertainment newspaper, Nellie was interested in getting Hal Roach to approach her son to participate in the Our Gang series in Hollywood. Roach offered $5 a day to Joe, Jr., while the other young stars were paid five times more. As he was getting bit parts in films, he began working with established film stars such as Joel McCrea, Colleen Moore, Clark Gable, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. and Jean Harlow. While selling newspapers around the corner, he enrolled in the Hollywood Professional School and later attended Hollywood High School, from which he graduated in 1938.

Career

Mickey McGuire

The Yules separated in 1924 during a slump in vaudeville when Rooney was 4 years old, and in 1925, Nell Yule moved with her son from Brooklyn to Hollywood, where she managed a tourist home. Joe Yule Jr.'s first film appearance came in 1926, when he was in the short Not to be Trusted,[2][12] but his breakthrough film role came a year later.

Fontaine Fox had placed a newspaper ad for a dark-haired child to play the role of "Mickey McGuire" in a series of short films. Lacking the money to have her son's hair dyed, Mrs. Yule took her son to the audition after applying burnt cork to his scalp.[13] Joe got the role and became "Mickey" for 78 of the comedies, running from 1927–36, starting with Mickey's Circus, his first starring role, released September 4, 1927. The film was long believed lost, but in 2014 was reported found in the Netherlands.[14]

The Mickey McGuire films were adapted from the Toonerville Trolley comic strip, which contained a character named Mickey McGuire. Joe Yule briefly became Mickey McGuire legally in order to trump an attempted copyright lawsuit (if it was his legal name, the film producer Larry Darmour did not owe the comic strip writers royalties). His mother also changed her surname to McGuire in an attempt to bolster the argument, but the film producers lost. The litigation settlement awarded damages to the owners of the cartoon character, compelling the twelve-year-old actor to refrain from calling himself Mickey McGuire on- and off-screen.[15]

Rooney later claimed that during his Mickey McGuire days he met cartoonist Walt Disney at the Warner Brothers studio, and that Disney was inspired to name Mickey Mouse after him,[16] although Disney always said that he had changed the name from "Mortimer Mouse" to "Mickey Mouse" on the suggestion of his wife.[17]

In 1930 Mrs. Yule sought to change her name to McGuire, "because Joe Yule Jr., her son, plays 'Mickey' in pictures and consequently her friends all know her by his screen name."[18]

During an interruption in the series in 1932, Mrs. Yule made plans to take her son on a 10-week vaudeville tour as McGuire, and Fox sued successfully to stop him from using the name. Mrs. Yule suggested the stage name of Mickey Looney for her comedian son. He altered this to Rooney, which did not infringe upon the copyright of Warner Brothers' animation series called Looney Tunes.[13] Rooney made other films in his adolescence, including several more of the McGuire films, and signed with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1934. MGM cast Rooney as the teenage son of a judge in 1937's A Family Affair, setting Rooney on the way to another successful film series.

Andy Hardy, Boys Town and Hollywood stardom

In 1937, Rooney was selected to portray Andy Hardy in A Family Affair, which MGM had planned as a B-movie.[13] Rooney provided comic relief as the son of Judge James K. Hardy, portrayed by Lionel Barrymore (although Lewis Stone would play the role of Judge Hardy in subsequent films). The film was an unexpected success, and led to 13 more Andy Hardy films between 1937 and 1946, and a final film in 1958.

According to author Barry Monush, MGM wanted the Andy Hardy films to appeal to all family members. Rooney's character would portray a typical "anxious, hyperactive, girl-crazy teenager", and he soon became the unintended main star of the films. Although some critics describe the series of films as "sweet, overly idealized, and pretty much interchangeable," their ultimate success was because they gave viewers a "comforting portrait of small-town America that seemed suited for the times", with Rooney instilling "a lasting image of what every parent wished their teen could be like."[19]

Behind the scenes, however, Rooney was in fact very much the "hyperactive girl-crazy teenager" he portrayed. Wallace Beery, his co-star in Stablemates, described him as a "brat", but a "fine actor".[20] MGM head Louis B. Mayer found it necessary to manage Rooney's public image, explains historian Jane Ellen Wayne:

Mayer naturally tried to keep all his child actors in line, like any father figure. After one such episode, Mickey Rooney replied, "I won't do it. You're asking the impossible." Mayer then grabbed young Rooney by his lapels and said, "Listen to me! I don't care what you do in private. Just don't do it in public. In public, behave. Your fans expect it. You're Andy Hardy! You're the United States! You're the Stars and Stripes. Behave yourself! You're a symbol!" Mickey nodded. "I'll be good, Mr. Mayer. I promise you that." Mayer let go of his lapels, "All right," he said.[21]

In hindsight, 50 years later, Rooney saw these early confrontations with Mayer as necessary to his developing into a leading film star: "Everybody butted heads with him, but he listened and you listened. And then you'd come to an agreement you could both live with. … He visited the sets, he gave people talks … What he wanted was something that was American, presented in a cosmopolitan manner."[22]:323

In 1937, Rooney made his first film alongside Judy Garland with Thoroughbreds Don't Cry. Garland and Rooney became close friends as they co-starred in future films and became a successful song-and-dance team. Audiences delighted in seeing the "playful interactions between the two stars showcase a wonderful chemistry."[23] Along with three of the Andy Hardy films, where she portrayed a girl with a crush on Andy, they appeared together in a string of successful musicals, including the Oscar-nominated Babes in Arms (1939). During an interview in the 1992 documentary film MGM: When the Lion Roars, Rooney describes their friendship:[24]

Judy and I were so close we could've come from the same womb. We weren't like brothers or sisters but there was no love affair there; there was more than a love affair. It's very, very difficult to explain the depths of our love for each other. It was so special. It was a forever love. Judy, as we speak, has not passed away. She's always with me in every heartbeat of my body.

In 1937, Rooney received top billing as Shockey Carter in Hoosier Schoolboy but his breakthrough-role as a dramatic actor came in 1938's Boys Town opposite Spencer Tracy as Father Flanagan, who runs a home for wayward and homeless boys in Omaha, Nebraska, and helps the boys get their lives back together. Rooney was awarded a special Juvenile Academy Award in 1939[25] and Tracy won the Oscar for Best Actor. Wayne describes one of the "most famous scenes" in the film, where tough young Rooney is playing poker with a cigarette in his mouth, his hat is cocked and his feet are up on the table. "Tracy grabs him by the lapels, throws the cigarette away and pushes him into a chair. 'That's better,' he tells Mickey."[21]

The popularity of his films made Rooney the biggest box-office draw in 1939, 1940 and 1941.[26] For their roles in Boys Town, Rooney and Tracy won first and second place in the Motion Picture Herald 1940 National Poll of Exhibitors, based on the box office appeal of 200 players. Boys' Life magazine wrote, "Congratulations to Messrs. Rooney and Tracy! Also to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer we extend a hearty thanks for their very considerable part in this outstanding achievement."[27] Actor Laurence Olivier once called Rooney "the greatest actor of them all.".[28] In 1939, he was the first of many Hollywood stars to appear as an animated caricature in the Donald Duck cartoon The Autograph Hound.

A major star in the early 1940s, he appeared on the cover of Time magazine in 1940, timed to coincide with the release of Young Tom Edison;[29] the cover story began:[30]

Hollywood's No. 1 box office bait in 1939 was not Clark Gable, Errol Flynn or Tyrone Power, but a rope-haired, kazoo-voiced kid with a comic-strip face, who until this week had never appeared in a picture without mugging or overacting it. His name (assumed) was Mickey Rooney, and to a large part of the more articulate U.S. cinema audience, his name was becoming a frequently used synonym for brat.

During his long career, Rooney also worked with many of the silver screen's greatest leading ladies, including Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet (1944) and Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961)."[31] Rooney's "bumptiousness and boyish charm" as an actor would develop more "smoothness and polish" over the years, writes biographer Scott Eyman. The fact that Rooney fully enjoyed his life as an actor played a large role in those changes:

You weren't going to work, you were going to have fun. It was home, everybody was cohesive; it was family. One year I made nine pictures; I had to go from one set to another. It was like I was on a conveyor belt. You did not read a script and say, "I guess I'll do it." You did it. They had people that knew the kind of stories that were suited to you. It was a conveyor belt that made motion pictures.[22]:224

Clarence Brown, who directed Rooney in his Oscar-nominated performance in The Human Comedy (1943) and again in National Velvet (1944), enjoyed working with Rooney in films:

Mickey Rooney is the closest thing to a genius that I ever worked with. There was Chaplin, then there was Rooney. The little bastard could do no wrong in my book … All you had to do with him was rehearse it once.[32]

In 1991, Rooney was honored by the Young Artist Foundation with its Former Child Star "Lifetime Achievement" Award recognizing his achievements within the film industry as a child actor.[33] After presenting the award to Rooney, the foundation subsequently renamed the accolade "The Mickey Rooney Award" in his honor.[34][35]

World War II and career decline

In June 1944, Rooney was inducted into the United States Army.[36] He served more than 21 months, until shortly after the end of World War II in Special Services entertaining the troops in America and Europe. He spent part of the time as a radio personality on the American Forces Network and was awarded the Bronze Star Medal for entertaining troops in combat zones. In addition to the Bronze Star Medal, Rooney also received the Army Good Conduct Medal, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, and World War II Victory Medal, for his military service.[37][38][39]

After his return to civilian life, his career slumped. Now an adult with a height of only 5'2",[40] he could no longer play the role of a teenager yet lacked the stature of most leading men. He appeared in a number of films, including Words and Music in 1948, which paired him for the last time with Garland on film (he appeared with her on one episode as a guest on her CBS variety series in 1963). He briefly starred in a CBS radio series, Shorty Bell, in the summer of 1948, and reprised his role as "Andy Hardy", with most of the original cast, in a syndicated radio version of The Hardy Family in 1949 and 1950 (repeated on Mutual during 1952).[41]

In 1949 Variety reported that Rooney had renegotiated his deal with MGM. He agreed to make one film a year for them for five years at $25,000 a movie (his fee until then had been $100,000 but Rooney wanted to enter independent production.) Rooney claimed he was unhappy with the billing MGM gave him for Words and Music.[42]

His first television series, The Mickey Rooney Show: Hey, Mulligan (created by Blake Edwards with Rooney as his own producer), appeared on NBC television for 32 episodes between August 28, 1954, and June 4, 1955. In 1951, he directed a feature film for Columbia Pictures, My True Story starring Helen Walker. Rooney also starred as a ragingly egomaniacal television comedian, loosely based on Red Buttons, in the live 90-minute television drama The Comedian, in the Playhouse 90 series on the evening of Valentine's Day in 1957, and as himself in a revue called The Musical Revue of 1959 based on the 1929 film The Hollywood Revue of 1929, which was edited into a film in 1960, by British International Pictures.[43]

In 1958, Rooney joined Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra in hosting an episode of NBC's short-lived Club Oasis comedy and variety show. In 1960, Rooney directed and starred in The Private Lives of Adam and Eve, an ambitious comedy known for its multiple flashbacks and many cameos. In the 1960s, Rooney returned to theatrical entertainment. He still accepted film roles in undistinguished films but occasionally would appear in better works, such as Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962), It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), and The Black Stallion (1979).[43]

He portrayed a Japanese character, Mr. Yunioshi, in the 1961 film version of Truman Capote's novella Breakfast at Tiffany's. His performance was criticized in subsequent years as a racist stereotype.[44][45] In 2008, after defending his performance as Yunioshi for many years, Rooney said that if he had known he was going to offend people he wouldn't have done it.[46]

On December 31, 1961, he appeared on television's What's My Line and mentioned that he had already started enrolling students in the MRSE (Mickey Rooney School of Entertainment). His school venture never came to fruition. This was a period of professional distress for Rooney; as a childhood friend, director Richard Quine put it: "Let's face it. It wasn't all that easy to find roles for a 5-foot-3 man who'd passed the age of Andy Hardy."[47] In 1962, his debts had forced him into filing for bankruptcy.[48]

In 1966, while Rooney was working on the film Ambush Bay in the Philippines, his wife Barbara Ann Thomason (aka Tara Thomas, Carolyn Mitchell), a former pinup model and aspiring actress who had won 17 straight beauty contests in Southern California, was found dead in their bed. Beside her was her lover, Milos Milos, an actor friend of Rooney's. Detectives ruled it murder-suicide, which was committed with Rooney's own gun.[49]

His appearance in John Frankenheimer's The Extraordinary Seaman in 1969 complemented David Niven's performance, and resulted in a friendship with co-star Faye Dunaway, which lasted until his death.[50]

Rooney was awarded an Academy Juvenile Award in 1938, and in 1983 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences voted him their Academy Honorary Award for his lifetime of achievement.

Character roles and Broadway comeback

Television roles

In addition to his movie roles, Rooney made numerous guest-starring roles as a television character actor for nearly six decades, beginning with an episode of Celanese Theatre. The part led to other roles on such television series as Schlitz Playhouse, Playhouse 90, Producers' Showcase, Alcoa Theatre, The Soldiers, Wagon Train, General Electric Theater, Hennesey, The Dick Powell Theatre, Arrest and Trial, Burke's Law, Combat!, The Fugitive, Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre, The Jean Arthur Show, The Name of the Game, Dan August, Night Gallery, The Love Boat, Kung Fu: The Legend Continues, Murder, She Wrote, The Golden Girls among many others.[43]

In 1961, he guest-starred in the 13-week James Franciscus adventure–drama CBS television series The Investigators. In 1962, he was cast as himself in the episode "The Top Banana" of the CBS sitcom, Pete and Gladys, starring Harry Morgan and Cara Williams.[43]

In 1963, he entered CBS's The Twilight Zone, giving a one-man performance in the episode "The Last Night of a Jockey". Also in 1963, in 'The Hunt' episode 9, season 1 for Suspense Theater, he played the sadistic sheriff hunting the young surfer played by James Caan. In 1964, he launched another half-hour sitcom, Mickey, on ABC. The story line had "Mickey" operating a resort hotel in southern California. His own son Tim Rooney appeared as his character's teenage son on this program, and Emmaline Henry starred as Rooney's wife. The program lasted for 17 episodes, ending primarily due to the suicide of co-star Sammee Tong in October 1964.[43][51]

Rooney garnered a Golden Globe and an Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Limited Series or a Special for his role in 1981's Bill. Playing opposite Dennis Quaid, Rooney's character was a mentally handicapped man attempting to live on his own after leaving an institution. His acting quality in the film has been favorably compared to other actors who took on similar roles, including Sean Penn, Dustin Hoffman and Tom Hanks.[52] He reprised his role in 1983's Bill: On His Own, earning an Emmy nomination for the turn.[43]

Rooney did voice acting from time to time. He provided the voice of Santa Claus in four stop-motion animated Christmas TV specials: Santa Claus Is Comin' to Town (1970), The Year Without a Santa Claus (1974), Rudolph and Frosty's Christmas in July (1979) and A Miser Brothers' Christmas (2008). In 1995, he appeared as himself on The Simpsons episode "Radioactive Man".[43]

After starring in one unsuccessful TV series and turning down an offer for a huge TV series, Rooney finally hit the jackpot, at 70, when he was offered a starring role on the Family Channel's The Adventures of the Black Stallion, where he reprised his role as Henry Dailey in the film of the same name, eleven years earlier. The show was based on a novel by Walter Farley. For this role, he had to travel to Vancouver.

Rooney appeared in television commercials for Garden State Life Insurance Company in 1999, alongside his wife, Jan. In commercials shown in 2007, he can be seen in the background washing imaginary dishes.

Broadway shows

A major turning point came in 1979, when Rooney made his Broadway debut in the acclaimed stage play Sugar Babies, a musical revue tribute to the burlesque era costarring former MGM dancing star Ann Miller. Aljean Harmetz noted that "Mr. Rooney fought over every skit and argued over every song and almost always got things done his way. The show opened on Broadway on October 8, 1979, to rave reviews, and this time he did not throw success away. The show turned out to be a spectacular hit,"[53] and Rooney and Miller performed the show 1,208 times in New York and then toured with it for five years, including eight months in London.[54] Co-star Miller recalls that Rooney "never missed a performance or a chance to ad-lib or read the lines the same way twice, if he even stuck to the script."[48] Biographer Alvin Marill states that "at 59, Mickey Rooney was reincarnated as a baggy-pants comedian—back as a top banana in show biz in his belated Broadway debut."[48]

Following this, he toured as Pseudelous in Stephen Sondheim's A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. In the 1990s, he returned to Broadway for the final months of Will Rogers Follies, playing the ghost of Will's father. On television, he starred in the short-lived sitcom, One of the Boys, along with two unfamiliar young stars, Dana Carvey and Nathan Lane, in 1982.[43]

He toured Canada in a dinner theatre production of The Mind with the Naughty Man in the mid-1990s. He played The Wizard in a stage production of The Wizard of Oz with Eartha Kitt at Madison Square Garden. Kitt was later replaced by Jo Anne Worley.

Published work

Rooney wrote a memoir titled Life is Too Short, published by Villard Books in 1991. A Library Journal review said that "From title to the last line, 'I'll have a short bier', Rooney's self-deprecating humor powers this book." He wrote a novel about a child star, published in 1994, The Search For Sunny Skies.[55]

Final years

Despite the millions of dollars that he earned over the years, such as his $65,000 a week earnings from Sugar Babies, Rooney was plagued by financial problems late in life. His longtime gambling habit caused him to "gamble away his fortune again and again." He declared bankruptcy for a second time in 1996, and described himself as "broke" in 2005. He kept performing on stage and in the movies. Rooney and his wife, Jan, toured the country in 2005 through 2011 in a musical revue called Let's Put on a Show. Vanity Fair called it "a homespun affair full of dog-eared jokes" that featured Rooney singing George Gershwin songs.[5]

In 2006, Rooney played Gus in Night at the Museum, a comedy starring Ben Stiller and Robin Williams.[56] He returned to play the role again in the sequel Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian in 2009, in a scene that was deleted from the final film.[57]

On May 26, 2007, he was grand marshal at the Garden Grove Strawberry Festival. Rooney made his British pantomime debut, playing Baron Hardup in Cinderella, at the Sunderland Empire Theatre over the 2007 Christmas period,[58][59] a role he reprised at Bristol Hippodrome in 2008 and at the Milton Keynes theatre in 2009.[60]

In 2011, Rooney made a brief cameo appearance in The Muppets and in 2014, at age 93, he reprised his role as Gus in Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb.[61] Although confined to a wheelchair, he was described by director Shawn Levy as "energetic and so pleased to be there. He was just happy to be invited to the party."[62]

An October 2015 article in The Hollywood Reporter maintained that Rooney was frequently abused and financially depleted by his closest relatives in the last years of his life. The article said that it was clear that "one of the biggest stars of all time, who remained aloft longer than anyone in Hollywood history, was in the end brought down by those closest to him. He died humiliated and betrayed, nearly broke and often broken."[2] Rooney suffered from bipolar disorder and attempted suicide two or three times over the years, with resulting hospitalizations reported as "nervous breakdowns".[2]

Personal life

Rooney was married eight times, with six of the marriages ending in divorce. In the 1960s and 1970s, he was often the subject of comedians' jokes due to his alleged inability to stay married. At the time of his death, he was married to Jan Chamberlin Rooney, although they had separated in June 2012.[63] He had a total of nine children, as well as nineteen grandchildren and several great-grandchildren.

Rooney was a gambler, and was addicted to sleeping pills, which he was able to overcome in 2000, when he was in his late 70s.[5]

Rooney married his first wife, Ava Gardner, Hollywood starlet at the age of 21 (she was 19) in 1942, but the two were divorced in 1943, well before she became a star in her own right. She divorced him because he couldn't remain faithful to her.[2] While stationed in the military in Alabama in 1944, Rooney met and married local beauty queen Betty Jane Phillips, who later became known as a singer under the name BJ Baker. They had two sons together. This marriage ended in divorce after he returned from Europe at the end of World War II. His marriage to actress Martha Vickers in 1949 produced one son but ended in divorce in 1951. He married actress Elaine Mahnken, better known as Elaine Devry, in 1952. They divorced in 1958.

In 1958, Rooney married Barbara Ann Thomason (stage name Carolyn Mitchell), but tragedy struck when she was murdered in 1966. He then married Barbara's best friend, Marge Lane. That marriage lasted 100 days. He was married to Carolyn Hockett from 1969–74, but financial instability ended the relationship. Finally, in 1978, Rooney married his eighth wife, Jan Chamberlin. Their marriage lasted longer than his previous seven combined, although they became estranged in 2012 and legally separated in 2014.[63]

On September 23, 2010, he celebrated his 90th birthday at Feinstein's at Loews Regency on the Upper East Side of New York City. Among those who attended the fete were Donald Trump, Regis Philbin, Nathan Lane and Tony Bennett.[64]

.jpg)

On February 16, 2011, Rooney was granted a temporary restraining order against Christopher Aber and Aber's wife, Christina. Aber was one of Jan Rooney's two sons from a previous marriage. The court order stated that the Abers were to stay 100 yards from Rooney, his stepson Mark Rooney and his wife, Charlene Rooney.[65] Mickey charged Chris and Christina Aber with elder abuse and fraud, and Rooney's attorneys alleged that Aber "threatens, intimidates, bullies and harasses Mickey" and refused to reveal the actor's finances to him, "other than to tell him that [he] is broke."[66]

On March 2, 2011, Rooney appeared before a special U.S. Senate committee that was considering legislation to curb elder abuse, testifying about the abuse he claimed to have suffered at the hands of family members. On March 27, 2011, all of Rooney's finances were permanently handed over to a conservator,[67] who called Rooney "completely competent."[66]

In April 2011, the temporary restraining order that Rooney was previously granted was replaced by a confidential settlement between Rooney and his stepson, Aber.[68] Christopher Aber and Jan Rooney denied all the allegations,[69][70] and after Rooney's death, Aber contended that Rooney was abusive to his wife and addicted to sleeping pills.[71] Rooney was arrested for beating his wife in February 1997, although prosecutors decided not to file battery charges against him.[72] In June 2012, Mickey requested through the Superior Court to reside with Mark and Charlene permanently and legally separated from his wife, Jan Rooney.

According to Mark Ellis, writing in Godreports,[73] Rooney said that he became a Christian after meeting what he believed was an angel in the form of a busboy at a casino coffee shop in Lake Tahoe, who told him "Mr. Rooney, Jesus Christ loves you very much."[73][74] According to Ellis, Rooney spent time as a member of the cult-like Church of Religious Science before espousing a more orthodox Christian faith. Rooney's eldest child, Mickey Rooney, Jr., is also a Christian, and has an evangelical ministry in Hemet, California.[75]

In May 2013, Rooney sold his home of many years, reportedly for $1,300,000, and split the proceeds with his wife, Jan.[12][76]

Marriages

| Wife | Years | Children |

|---|---|---|

| Ava Gardner | 1942–43 | |

| Betty Jane Rase (née Phillips) | 1944–49 | Mickey Rooney, Jr. (Joseph Yule III; born July 3, 1945) |

| Tim Rooney (Timothy Hayes Yule; January 4, 1947 – September 23, 2006) | ||

| Martha Vickers | 1949–51 | Theodore Michael Rooney (April 13, 1950 – July 2, 2016[77]) |

| Elaine Devry (a.k.a.: Elaine Davis) |

1952–58 | |

| Barbara Ann Thomason (a.k.a.: Tara Thomas, Carolyn Mitchell) |

1958–66 | Kelly Ann Rooney (born September 13, 1959) |

| Kerry Yule Rooney (born December 30, 1960) | ||

| Michael Joseph Rooney (born April 2, 1962) | ||

| Kimmy Sue Rooney (born September 13, 1963) | ||

| Marge Lane | 1966–67 | |

| Carolyn Hockett | 1969–75 | Jimmy Rooney (adopted from Carolyn's previous marriage; born in 1966) |

| Jonelle Rooney (born January 11, 1970) | ||

| Jan Chamberlin | 1978–2014 (separated, June 2012)[63] |

Death

On April 6, 2014, Rooney died of natural causes in his sleep at his stepson Mark Rooney's home in Los Angeles, California, at the age of 93.[78] He had gone for a nap after lunch, and family members called 911 when they sought to wake him and his breathing seemed labored. He was declared dead at 4 p.m.[79] Rooney was survived by his wife of 37 years, Jan Chamberlain, from whom he was separated,[63] as well as eight surviving children, two stepchildren, nineteen grandchildren, and several great-grandchildren.[80]

Rooney signed his will several weeks prior to his death. It disinherited all but one of his eight living children and his wife Jan, from whom he was estranged, and instructed his lawyer, rather than family, to manage his estate.[63] Rooney's lawyer disclosed that his client wanted to purchase a burial plot, but was unable to afford one. His estate had dwindled to $18,000, which was left to stepson Mark Rooney, the son of Jan Rooney. At the time of his death, Rooney owed back taxes to the IRS and the California Franchise Tax Board.[7] Rooney's talent agency, CMG Worldwide, said that medical bills were also owed and that contributions from the public were being accepted, with proceeds "donated to help assist with the debts and expenses of Mickey's estate."[8] Jan Rooney and seven of Rooney's eight biological children later filed separate court actions contesting the will.[81]

After his death, family members clashed over his burial and a court hearing on the matter was scheduled for April 11, 2014.[7][79]

On April 10, family members resolved their dispute, deciding that he would be interred at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. Rooney's conservator and Jan Rooney agreed to collaborate on a small funeral for family members, but with Christopher and Christina Aber, whom Rooney had accused of abuse, not being permitted to attend. The settlement headed off a potentially expensive lawsuit. His lawyer said that "Mickey had enough lawsuits in life for 10 people; the last thing he needs is for one over where he'll be buried."[82][83]

A group of family members and friends, including Mickey Rourke, held a memorial service on April 18. A private funeral, organized by another set of family members, was held at the cemetery on April 19. His eight surviving children said in a statement that they were barred from seeing Rooney during his final years.[84][85][86]

Legacy

Rooney was one of the last surviving actors of the silent picture era. His movie career spanned 88 years, from 1926 to 2014, continuing until shortly before his death. During his peak years from the late 1930s to the early 1940s, Rooney was among the top box-office stars in the United States.[87]

Rooney co-starred with other leading actors of the time, including Judy Garland, Wallace Beery and Spencer Tracy. Between the age of 15 and 25 he made forty-three pictures. Among those, his role as Andy Hardy became one of "Hollywood's best-loved characters," with Marlon Brando calling him "the best actor in films."[19] For his acting the part in fifteen Andy Hardy films, he received an honorary Oscar in 1938 for "bringing to the screen the spirit and personification of youth" and for "setting a high standard of ability and achievement."[88]

Rooney's talents were multiple. In an appraisal after his death, Nancy Jo Sales recounted in Vanity Fair that "He could sing, he could act, he could dance. He learned to play the banjo—scarily well—in a day. He played the drums like a pro. He was an expert golfer, a champion ping-pong player. He composed a symphony, Melodante, which he performed on the piano at Franklin Roosevelt's 1941 Inauguration Gala. Mickey was some kind of beautiful, talented monster."[5]

"There was nothing he couldn't do", said actress Margaret O'Brien.[87] MGM boss Louis B. Mayer treated him like a son and saw in Rooney "the embodiment of the amiable American boy who stands for family, humbug, and sentiment," writes critic and author, David Thomson.[89]

By the time Rooney was 20, his consistent portrayals of characters with youth and energy suggested that his future success was unlimited. Thomson also explains that Rooney's characters were able to cover a wide range of emotional types, and gives three examples where "Rooney is not just an actor of genius, but an artist able to maintain a stylized commentary on the demon impulse of the small, belligerent man:"[89]

Rooney's Puck in A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935) is truly inhuman, one of cinema's most arresting pieces of magic. … His toughie in Boys Town (1938) struts and bullies like something out of a nightmare and then comes clean in a grotesque but utterly frank outburst of sentimentality in which he aspires to the boy community. . . . His role as Baby Face Nelson (1957), the manic, destructive response of the runt against a pig society.[89]

By the end of the 1940s, Rooney's movie characters were no longer in demand and his career went downhill. "In 1938," he said, "I starred in eight pictures. In 1948 and 1949 together, I starred in only three."[88] However, film historian Jeanine Basinger notes that although his career "reached the heights and plunged to the depths, Rooney kept on working and growing, the mark of a professional." Some of the films which reinvigorated his popularity, were Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962), It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963) and The Black Stallion (1979). In the early 1980s, he returned to Broadway in Sugar Babies, and "found himself once more back on top."[88]

In an appreciation published after his death, The New Yorker's movie critic Richard Brody said of Rooney: "His live-wire expressiveness spoke of the can-do, will-do spirit that may have encouraged Depression-weary audiences with a dose of practical optimism, but the enforced razzle-dazzle showed only one side of his persona (and perhaps warped his personality). Rooney, in his more matter-of-fact (if less heralded) performances, holds the screen with a seemingly effortless intensity." Rooney, he said, was "a real movie star, whom the camera loved. To glance at him onscreen was to wonder what he was thinking, what he was feeling, what he'd do next — above all, to have the sense that he was running on bigger, wilder, stranger currents … his greatest role was always himself; no matter how extreme or how contained his performance, he was always bigger than any role he took."[90]

Basinger tries to encapsulate Rooney's career:

Rooney's abundant talent, like his film image, might seem like a metaphor for America: a seemingly endless supply of natural resources that could never dry up, but which, it turned out, could be ruined by excessive use and abuse, by arrogance or power, and which had to be carefully tended to be returned to full capacity. From child star to character actor, from movie shorts to television specials, and from films to Broadway, Rooney ultimately did prove he could do it all, do it well, and keep on doing it. His is a unique career, both for its versatility and its longevity.[88]

Filmography

Stage

|

|

Awards and honors

Awards

Honors

On February 8, 1960, Rooney was initiated into the Hollywood Walk of Fame with a star heralding his work in motion pictures, located at 1718 Vine Street, one for his television career located at 6541 Hollywood Boulevard, and a third dedicated to his work in radio, located at 6372 Hollywood Boulevard. On March 29, 1984, he received a fourth star, this one for his live performances, located at 6211 Hollywood Boulevard.[91]

In 1996, a Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs, California, Walk of Stars was dedicated to Rooney.[92]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "Mickey Rooney, an enduring star", bostonglobe.com, April 7, 2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gary Baum and Scott Feinberg (October 21, 2015). "Tears and Terror: The Disturbing Final Years of Mickey Rooney". The Hollywood Reporter. (Prometheus Global Media). Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Iconic Actor Mickey Rooney Dies At 93", CBS News, April 7, 2014.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times (April 7, 2014). "Mickey Rooney: A long and remarkable career in film, TV". latimes.com. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sales, Nancy Jo (April 7, 2014). "Mickey Rooney Blew Through Wives and Fortunes, but God, What a Talent!". Vanity Fair. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Mickey Rooney's estate goes to stepson who served as caregiver", cbc.ca, April 9, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Kim, Victoria; Ryan, Harriet (April 8, 2014). "Mickey Rooney's body goes unclaimed as family feuds over burial site". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- 1 2 "The Official Mickey Rooney Site". Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ↑ Life Is Too Short (1991 autobiography); ISBN 978-0-679-40195-7

- ↑ Bernstein, Adam (April 7, 2014). "Mickey Rooney dies at 93". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- ↑ Lertzman, Richard A.; Birnes, William J. (2015). The Life and Times of Mickey Rooney. Gallery Books. pp. 24–27. ISBN 1-5011-0096-3. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- 1 2 Duke, Alan; Leopold, Todd (April 7, 2014). "Legendary actor Mickey Rooney dies at 93". CNN.com. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Current Biography 1942. H.W. Wilson Co. (January 1942). pp. 704–06. ISBN 99903-960-3-5.

- ↑ Barnes, Mike (March 30, 2014). "Lost Mickey Rooney Film Is Found and Set for Preservation". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- ↑ Server, Lee, Ava Gardner - "Love is Nothing" (2006), St. Martin's Press

- ↑ Albin, Kira. Mickey Rooney: Hollywood, Religion and His Latest Show. GrandTimes.com Senior Magazine. 1995.

- ↑ Gabler, Neal, Walt Disney, (2006), Alfred A. Knopf

- ↑ Coons, Robbin (August 29, 1930). "Mother of Mickey McGuire Seeks to Change Her Name". The Evening Review. East Liverpool, Ohio. Retrieved January 10, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Monush, Barry. The Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors, Applause Theatre and Cinema Books (2003) pp. 648–51

- ↑ Marx, A. The Nine Lives of Mickey Rooney. Stein and Day (1986), p. 68; ISBN 0-8128-3056-3.

- 1 2 Wayne, Jane Ellen. The Leading Men of MGM, Carroll & Graf (2005) p. 246

- 1 2 Eyman, Scott. Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer, Simon & Schuster (2005)

- ↑ "Remembering Mickey Rooney With a Few of His Greatest Musical Performances", Slate.com, April 7, 2014.

- ↑ Rooney, Mickey. "The Lion Reigns Supreme", MGM: When the Lion Roars, 1992 miniseries

- ↑ "11th Academy Awards". Oscars.org. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ " By 1939 [Rooney] was the top box-office star in the world, a title he held for three consecutive years." Branagh, Kenneth (narrator). 1939: Hollywood's Greatest Year. Turner Classic Movies, 2009.

- ↑ Mathews, Franklin K. Boys' Life, April 1941, p. 23

- ↑ "Hollywood legend Mickey Rooney dies", USA Today, April 7, 2014

- ↑ "Young Tom Edison (1940)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

Time put Rooney on the cover, noting that his movies had grossed a whopping $30 million for MGM the previous year and praising him for 'his most sober and restrained performance to date' as young Edison, 'who (like himself) began at the bottom of the American heap, (like himself) had to struggle, (like himself) won, but a boy whose main activity (unlike Mickey's) was investigating, inventing, thinking.'

- ↑ "Cinema: Success Story". Time. March 18, 1940. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

Hollywood's No. 1 box office bait in 1939 was not Clark Gable, Errol Flynn or Tyrone Power, but a rope-haired, kazoo-voiced kid with a comic-strip face, who until this week had never appeared in a picture without mugging or overacting it. His name (assumed) was Mickey Rooney, and to a large part of the more articulate U. S. cinema audience, his name was becoming a frequently used synonym for brat.

- ↑ "Mickey Rooney Dead: Legendary Actor Dies At 93", Huffington Post, April 7, 2014.

- ↑ Basinger, Jeanine. The Star Machine, Alfred A. Knopf (2007) p. 442

- ↑ "12th Annual Youth in Film Awards". YoungArtistAwards.org. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- ↑ "13th Annual Youth in Film Awards". YoungArtistAwards.org. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- ↑ "23rd Annual Young Artist Awards". YoungArtistAwards.org. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- ↑ http://army.togetherweserved.com/army/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApps?cmd=ShadowBoxProfile&type=Person&ID=336424

- ↑ Bowman, John S. (2014). Pergolesi in the Pentagon. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9781499038774.

- ↑ Marill, Alvin H. (2004). Mickey Rooney: His Films, Television Appearances, Radio Work, Stage Shows, and Recordings. McFarland & Company. p. 37. ISBN 9780786420155.

- ↑ Lertzman, Richard A.; Birnes, William J. (2015). The Life and Times of Mickey Rooney. Simon and Schuster. p. 246. ISBN 9781501100987.

- ↑ "Mickey Rooney obituary: women liked me because I made them laugh". Theguardian.com. April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ↑ Dunning, John, On The Air: The Encyclopedia Of Old-Time Radio (1998), Oxford University Press; accessed November 16, 2015.

- ↑ Staff (April 13, 1949) "Rooney's $25,000 Per Metro Picture; He's Out to Cash in on Own Prods." Variety p.4

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mickey Rooney at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Durant, Yvonne (June 18, 2006). "Where Holly Hung Her Ever-So-Stylish Hat". New York Observed. The New York Times. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ↑ Dargis, Manohla (July 20, 2007). "Dude (Nyuck-Nyuck), I Love You (as If!)". The New York Times. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ↑ Yang, Jeff (April 8, 2014). "The Mickey Rooney Role Nobody Wants to Talk Much Abou". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ↑ Marx, Arthur (1987). The Nine Lives of Mickey Rooney. New York: Berkley. ISBN 978-0-425-10552-8.

- 1 2 3 Marill, Alvin H. (2005). Mickey Rooney: His Films, Television Appearances, Radio Work, Stage Shows, And Recordings. Jefferson NC: McFarland. p. 50. ISBN 0-7864-2015-4.

- ↑ Brockes, Emma (October 16, 2005). "Murder in Tinseltown". London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ↑ Twitter remembrance by Faye Dunaway

- ↑ Marx, Arthur, The Nine Lives Of Mickey Rooney (1986), Stein & Day

- ↑ "Mickey Rooney's Quietest Role", New York Times, April 7, 2014.

- ↑ Harmetz, Aljean (April 7, 2014). "Mickey Rooney, Master of Putting On a Show, Dies at 93". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ↑ video: "Ann Miller and Mickey Rooney at the Palladium, 1988" on YouTube 8 min.

- ↑ "Iconic Hollywood Actor Mickey Rooney Dies At 93". NPR.com. The Associated Press. April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ↑ "Night at the Museum".

- ↑ "Yahoo". Yahoo.

- ↑ Mickey Rooney makes panto debut, channel4.com, December 7, 2007.

- ↑ "Mickey Rooney: The Mickey show". London, UK: Independent.co.uk. December 14, 2008. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Review – Cinderella with Mickey Rooney, Milton Keynes Theatre". Westendwhingers.wordpress.com. December 6, 2009. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Mickey Rooney, 93 gears up to film Night At The Museum 3 in Canada". Dailymail.co.uk. February 19, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ↑ Alexander, Bryan (December 17, 2014). "Mickey Rooney gives one final 'Museum' moment". USA Today. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Duke, Alan (May 11, 2014). "Mickey Rooney's widow contests late actor's will". CNN.com. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Actor Mickey Rooney Turns 90 With Upper East Side Style". Ny1.com. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Mickey Rooney granted restraining order against stepson". Bbc.co.uk. February 16, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- 1 2 Feinberg, Scott (April 9, 2014). "A Star Is Burned: Mickey Rooney's Final Days Marred by Bizarre Family Feud". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ↑ "Mickey Rooney lawyer to control finances". Bbc.co.uk. March 27, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Mickey Rooney drops restraining order against stepson". Tmz.com. February 15, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ↑ Carole Fleck and Talia Schmidt, "Mickey Rooney Claims Elder Abuse: Actor's testimony to Congress helps spur bill for new crackdown", AARP Bulletin, March 2, 2011.

- ↑ Silverman, Stephen M. (March 3, 2011). "Mickey Rooney: 'Elder Abuse Made Me Feel Trapped'". People.com. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ↑ Collins, Laura (April 25, 2014). "Exclusive – Mickey Rooney's dark side revealed: Bitter stepson claims star was a violent husband addicted to sleeping pills". The Daily Mail. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ Wilson, Tracy (March 12, 1997). "Rooney Won't Be Charged With Abuse". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- 1 2 Ellis, Mark (April 8, 2014) "How Mickey Rooney's encounter with an angel led to his faith in Jesus Christ" Godreports

- ↑ Polatis, Kandra (April 19, 2016). "Mickey Rooney and faith: Hollywood legend's belief in Christ". Deseret News.

- ↑ Sanderson, Nancy. "Legend's Son at Home in Hemet: Mickey Rooney Jr., in Show Business Since Childhood, Is Also Involved in Ministry."The Press-Enterprise (Hemet, California), May 22, 2001.

- ↑ Hetherman, Bill (March 3, 2013). "Mickey Rooney's home to be sold for $1.3M to West Hills firm". Daily Breeze.

- ↑ http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/teddy-rooney-dead-mickey-rooneys-908325

- ↑ Nelson, Valerie J. (April 6, 2014). "Mickey Rooney dies at 93; show-business career spanned a lifetime". Los Angeles Times.

- 1 2 "Mickey Rooney cuts family out of will". The Guardian. April 9, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ↑ "BREAKING NEWS: Legendary Actor Mickey Rooney Dead at 93". Guardian Liberty Voice.

- ↑ Clark, Champ (May 13, 2014). "Mickey Rooney's Children Challenge His Will in Court". People.com. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ↑ Arkin, Daniel (April 10, 2014). "Mickey Rooney Family Resolves Tussle Over Remains". NBC News. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ↑ Kim, Victoria (April 10, 2014). "Rooney family ends dispute, agrees to bury actor at Hollywood Forever". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ↑ Durkin, Erin (April 20, 2014). "Mickey Rooney laid to rest in private funeral at Hollywood Forever Cemetery". New York Daily News. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ↑ Stevens, Matt (April 19, 2014). "Mickey Rooney funeral set for today at Hollywood Forever". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ↑ Parker, Mike (April 13, 2014). "Mickey Rooney died too poor to pay for his own Hollywood funeral". Daily Express. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- 1 2 Mccartney, Anthony. "Los Angeles: Iconic Hollywood actor Mickey Rooney dies at 93". MiamiHerald.com. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Bassinger, Jeanine; Unterburger, Amy L., ed. International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers: Actors and Actresses, 3rd ed., St. James Press, (1997) pp. 1053–56.

- 1 2 3 Thomson, David. The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, Alfred A. Knopf (2002) pp. 754–755

- ↑ Brody, Richard (April 7, 2014). "The Natural: Farewell, Mickey Rooney". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Mickey Rooney" Hollywood Walk of Fame website

- ↑ "Palm Springs Walk of Stars in order by dedication date" (PDF). Retrieved September 16, 2013.

Bibliography

- Willson, Dixie (1935). Little Hollywood Stars. Akron, OH, e New York: Saalfield Pub. Co..

- Zierold, Norman J. (1965). The Child Stars. New York: Coward-McCann.

- Best, Marc (1971). Those Endearing Young Charms: Child Performers of the Screen. South Brunswick and New York: Barnes & Co., pp. 220–224.

- Parish, James Robert (1976). Great Child Stars. New York: Ace Books.

- Edelson, Edward (1979). Great Kids of the Movies. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Marx, Arthur (1988) [1986] The Nine Lives Of Mickey Rooney. New York: Berkley Publishing Group. ISBN 0-425-10552-0

- Dye, David (1988). Child and Youth Actors: Filmography of Their Entire Careers, 1914-1985. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., pp. 201–205.

- Rooney, Mickey (1991) Life Is Too Short. New York: Villard Books ISBN 0-679-40195-4

- Holmstrom, John (1996). The Moving Picture Boy: An International Encyclopaedia from 1895 to 1995, Norwich, Michael Russell, pp. 100–102.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mickey Rooney. |

- Official website

- Mickey Rooney at the Internet Movie Database

- Mickey Rooney at the TCM Movie Database

- Mickey Rooney at the Internet Broadway Database

- Mickey Rooney at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Mickey Rooney at Find a Grave

- Mickey Rooney on the Phil Silvers Show

- "Mickey Rooney on America, Christ and Judy Garland: The Hollywood Legend Speaks Out." Montreal Mirror interview 1998. Republished on a blog as Montreal Mirror has dissolved.

- Mickey Rooney at Virtual History

- Fate Slaps Down Andy Hardy http://filmnoirfoundation.org/sentinel-article/MickeyRooney.pdf

- Mickey Rooney interview video at the Archive of American Television

- Interview with Hollywood Reporter, July 2010