History of Transylvania

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Romania |

|

|

Post-Revolution |

|

|

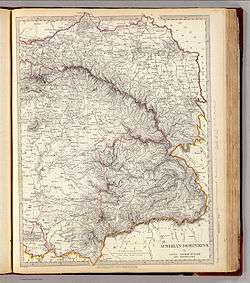

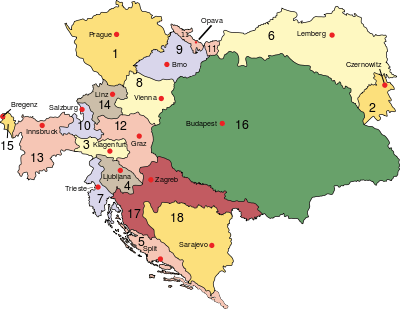

Transylvania is a historical region in central Romania. It was part of the Dacian Kingdom (1st–2nd centuries CE), Roman Dacia (2nd–3rd centuries), the Hunnic Empire (4th–5th centuries), the Kingdom of the Gepids (5th–6th centuries), the Avar Khaganate (6th–9th centuries) and the 9th century First Bulgarian Empire. During the late 9th century, western Transylvania was reached by the Hungarian conquerors[1] and later it became part of the Kingdom of Hungary, formed in 1000 CE. After the Battle of Mohács in 1526 it belonged to the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom, from which the Principality of Transylvania emerged. During most of the 16th and 17th centuries, the principality was a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire; however, the principality had dual suzerainty (Ottoman and Habsburg).[2][3] In 1690, the Habsburgs gained possession of Transylvania through the Hungarian crown.[4][5][6] After 1711[7] Habsburg control of Transylvania was consolidated, and Transylvanian princes were replaced with Habsburg imperial governors.[8][9] After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, the separate status[10] of Transylvania ceased; it was incorporated into the Kingdom of Hungary (Transleithania) as part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire.[11] After World War I, Transylvania became part of Romania. In 1940 Northern Transylvania reverted to Hungary as a result of the Second Vienna Award, but it was reclaimed by Romania after the end of World War II.

Due to its varied history the population of Transylvania is ethnically, linguistically, culturally and religiously diverse. From 1437 to 1848 political power in Transylvania was shared among the mostly Hungarian nobility, German burghers and the seats of the Székelys (a Hungarian ethnic group). The population consisted of Romanians, Hungarians (particularly Székelys) and Germans. The majority of the present population is Romanian, but large minorities (mainly Hungarian and Roma) preserve their traditions. However, as recently as the communist era ethnic-minority relations remained an issue of international contention. This has abated (but not disappeared) since the Revolution of 1989 restored democracy in Romania. Transylvania retains a significant Hungarian-speaking minority, slightly less than half of which identify themselves as Székely.[12] Ethnic Germans in Transylvania (known as Saxons) comprise about one percent of the population; however, Austrian and German influences remain in the architecture and urban landscape of much of Transylvania.

The region's history may be traced through the religions of its inhabitants. Most Romanians in Transylvania belong to the Eastern Orthodox Church faith, but from the 18th to the 20th centuries the Romanian Greek-Catholic Church also had substantial influence. Hungarians primarily belong to the Roman Catholic or Reformed Churches; a smaller number are Unitarians. Of the ethnic Germans in Transylvania, the Saxons have primarily been Lutheran since the Reformation; however, the Danube Swabians are Catholic. The Baptist Union of Romania is the second-largest such body in Europe; Seventh-day Adventists are established, and other evangelical churches have been a growing presence since 1989. No Muslim communities remain from the era of the Ottoman invasions. As elsewhere, anti-Semitic 20th century politics saw Transylvania's once sizable Jewish population greatly reduced by the Holocaust and emigration.

Ancient history

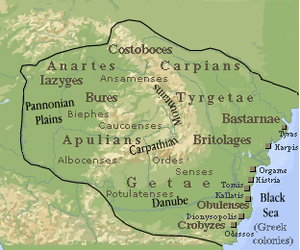

Part of Dacian state

Herodotus gives an account of the Agathyrsi, who lived in Transylvania during the fifth century BC. He described them as a luxurious people who enjoyed wearing gold ornaments.[13] Herodotus also claimed that the Agathyrsi held their wives in common, so all men would be brothers.[14]

A kingdom of Dacia existed at least as early as the early second century BC under King Oroles. Under Burebista, the foremost king of Dacia and a contemporary of Julius Caesar, the kingdom reached its maximum extent. The area now constituting Transylvania was the political center of Dacia.

The Dacians are often mentioned by Augustus, according to whom they were compelled to recognize Roman supremacy. However, they were not subdued and in later times crossed the frozen Danube during winter and ravaging Roman cities in the recently acquired Roman province of Moesia.

The Dacians built several important fortified cities, among them Sarmizegetusa (near the present Hunedoara). They were divided into two classes: the aristocracy (tarabostes) and the common people (comati).

Roman Dacia

The Roman Empire expansion in the Balkans brought the Dacians into open conflict with Rome. During the reign of Decebalus, the Dacians were engaged in several wars with the Romans from 85 to 89 AD. After two reverses the Romans gained an advantage, but were obliged to make peace due to the defeat of Domitian by the Marcomanni. As a result, the Dacians were left independent, but had to pay an annual tribute to the emperor. Following his subjugation Decebalus complied with Rome for a time, but was soon inciting revolt among the tribes and pillaging Roman colonies across the Danube.

Intrepid and optimistic, Trajan rallied his forces once more in 106 for a second war against Dacia. Unlike the first conflict, the second war involved several skirmishes that proved costly to the Roman military (who, facing large numbers of allied tribes, struggled to attain a decisive victory). Eventually, however, Rome prevailed and took Dacia. An assault against the capital, Sarmizegetusa Regia, proved successful and it was burned to the ground. Decebalus fled, but soon committed suicide rather than face capture.

In 101 the emperor Trajan began a military campaign against the Dacians, which included a siege of Sarmizegetusa Regia and the occupation of part of the country. Decebalus was left as a client king under a Roman protectorate. Three years later, the Dacians rebelled and destroyed the Roman troops in Dacia. The second campaign (105–106) ended with the suicide of Decebalus and the conversion of parts of Dacia into the Roman province of Dacia Trajana. The history of the Dacian Wars was written by Cassius Dio, and a commentary is on Trajan's Column in Rome.

The battle for Sarmizegetusa Regia took place in the early summer of 106 BC with the participation of the II Adiutrix and IV Flavia Felix legions and a detachment (vexillatio) from the Legio VI Ferrata. The Dacians repelled the first attack, but the water pipes from the Dacian capital were destroyed. The city was on fire, the pillars of the sacred sanctuaries were cut down and the fortification system was destroyed; however, the war continued. Through the treason of Bacilis (a confidant of the Dacian king), the Romans found Decebalus' treasure in the Strei River (estimated by Jerome Carcopino as 165,500 kg of gold and 331,000 kg of silver). The last battle with the army of the Dacian king took place at Porolissum (Moigrad).

Dacian culture encouraged its soldiers to not fear death, and it was said that they left for war merrier than for any other journey. In his retreat to the mountains, Decebalus was followed by Roman cavalry led by Tiberius Claudius Maximus. The Dacian religion of Zalmoxis permitted suicide as a last resort by those in pain and misery, and the Dacians who heard Decebalus' last speech dispersed and committed suicide. Only the king tried to retreat from the Romans, hoping that he could find in the mountains and forests the means to resume the battle, but the Roman cavalry followed him closely. After they almost caught him, Decebalus committed suicide by slashing his throat with his sword (falx). His death scene is depicted on Trajan's Column.

Post-Roman Dacia

The Romans had gold mines in the province and built access roads and forts (such as Abrud) to protect them. The region developed a strong infrastructure and an economy based on agriculture, cattle farming and mining. Colonists from Thracia, Moesia, Macedonia, Gaul, Syria and other Roman provinces were brought in to settle the land, developing cities like Apulum (now Alba Iulia) and Napoca (now Cluj Napoca) into municipiums and colonias.

The Dacians frequently rebelled, most notably after the death of Trajan. Sarmatians and Burs were allowed to settle in Dacia Trajana after repeated clashes between native Dacians and the Roman administration. During the third century, increasing pressure from the Free Dacians and Visigoths forced the Romans to abandon Dacia Trajana.

In 271, the Roman emperor Aurelian evacuated the Roman population from Dacia Trajana and resettled them across the Danube in the newly established Dacia Aureliana inside former Moesia Superior. The abandonment of Dacia Trajana is mentioned by the historian Eutropius in Liber IX of his Breviarum:

The province of Dacia, which Trajan had formed beyond the Danube, he gave up, despairing, after all Illyricum and Moesia had been depopulated, of being able to retain it. Roman citizens, removed from the town and lands of Dacia, he settled in the interior of Moesia, calling that Dacia which now divides the two Moesiae, and which is on the right hand of the Danube as it runs to the sea, whereas Dacia was previously on the left— Eutropius, Breviarium historiae romana – Liber IX, XV

| Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Part of the Vulgar Latin-speaking, Christian Daco-Roman (Proto-Romanian) population flourished in remote communities, evidenced by findings from the fourth to the seventh centuries including Roman coins, sections of Latin inscriptions (such as the Biertan Donarium) and early Christian artifacts.[15]

Before their withdrawal the Romans negotiated an agreement with the Goths in which Dacia remained Roman territory, and a few Roman outposts remained north of the Danube. The Thervingi, a Visigothic tribe, settled in the southern part of Transylvania and the Ostrogoths lived on the Pontic-Caspian steppe.[15]

About 340, Ulfilas brought Acacian Arianism to the Goths in Guthiuda, and the Visigoths (and other Germanic tribes) became Arians.

Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages: the great migrations

The Goths were able to defend their territory for about a century against the Gepids, Vandals and Sarmatians;[15] however, the Visigoths were unable to preserve the region's Roman infrastructure. Transylvania's gold mines were unused during the Early Middle Ages.

By 376 a new wave of migratory people, the Huns, reached Transylvania, triggering conflict with the Visigothic kingdom. Hoping to find refuge from the Huns, Fritigern (a Visigothic leader) appealed to the Roman emperor Valens in 376 to be allowed to settle with his people on the south bank of the Danube. However, a famine broke out and Rome was unable to supply them with food or land. As a result, the Goths rebelled against the Romans for several years.

The Huns fought the Alans, Vandals, and Quadi, forcing them toward the Roman Empire. Pannonia became the centre during the peak of Attila's reign (435–453).[15]

After Attila's death, the Hunnic empire disintegrated. In 455 the Gepids (under king Ardarich) conquered Pannonia, allowing them to settle for two centuries in Transylvania.[15] Their rule ended with attacks by the Lombards and Avars in 567.[15] Very few Gepid sites (such as cemeteries in the Banat region) after 600 remain; they were apparently assimilated by the Avar empire.

By 568 the Avars, under their khagan Bayan, established an empire in the Carpathian Basin that lasted for 250 years. During this period the Slavs were allowed to settle inside Transylvania. The Avars declined with the rise of Charlemagne's Frankish empire. After a war between the khagan and Yugurrus from 796 to 803, the Avars were defeated. The Transylvanian Avars were subjugated by the Bulgars under Khan Krum at the beginning of the ninth century; Transylvania and eastern Pannonia were incorporated into the First Bulgarian Empire.

In 862 Prince Rastislav of Moravia rebelled against the Franks and, after hiring Magyar troops, won his independence; this was the first time that Magyar expeditionary troops entered the Carpathian Basin.[17] After a Bulgar and Pecheneg attack, the Magyar tribes crossed the Carpathians around 896 and occupied the basin without significant resistance. According to eleventh-century tradition, the road taken by the Hungarians under Prince Álmos took them first to Transylvania in 895. This is supported by an eleventh-century Russian tradition that the Hungarians moved to the Carpathian Basin by way of Kiev.[18] According to supporters of the Daco-Roman continuity theory, Transylvania was populated by Romanians at the time of the Hungarian conquest.[19] Opponents of this theory assert that Transylvania was sparsely inhabited by peoples of Slavic origin and Turkic people.[20] The year of the conquest of Transylvania is unknown; the earliest Magyar artifacts found in the region date to the first half of the 10th century.[21] A coin minted under Berthold, Duke of Bavaria found near Turda indicates that Transylvanian Magyars participated in western military campaigns.[22] Although their defeat in the 955 Battle of Lechfeld ended Magyar raids against western Europe, raids on the Balkan Peninsula continued until 970. Linguistic evidence suggests that after their conquest, the Magyars inherited the local social structures of the conquered Pannonian Slavs;[23] in Transylvania, there was intermarriage between the Magyar ruling class and the Slavic élite.[22]

Hungarian conquest

Gelou is a figure in the Gesta Hungarorum (Latin for The Deeds of the Hungarians), а medieval work written by an author known as "Anonymus" probably at the end of the 12th century (about 300 years after the Hungarian conquest, which began in 895–96). Gelou is described as "a certain Vlach" (originally quidam Blacus, Vlach and Blacus meaning "Romanian") and a leader of the Vlachs and Slavs in Transylvania with his capital at Doboka. He was said to be defeated by one of the seven Hungarian dukes, Töhötöm (Tuhutum in the original Latin, also known as Tétény). Romanian historian Neagu Djuvara asserts that Gelou could be connected with the ancient Thracian toponym Gelupara (para meaning "town") and the modern toponym Gilău, the name of a village and a river in Cluj (Kolozs). According to Bulgarian linguist Ivan Duridanov, Thracian and Dacian were two distinct Indo-European languages. Many village names in ancient Thracia were composites, with the suffixes -para (-phara, -pera, -parn, etc.) meaning "village". Such names are not found in Dacia (on the northern side of the Danube). The Dacian linguistic area is characterized by composite names ending in -dava (-deva, -daua, -daba, etc.) or "town".[25] Hungarian historians assert that Gelou was created by the author from the name of the village of Gelou (Hungarian: Gyalu) as the legendary enemy of the Hungarian noble families about whose deeds he wrote.

Another legendary leader of Transylvania was Glad. He was, according to the Gesta Hungarorum, a voivod from Bundyn (Vidin) who ruled the territory of Banat in the Vidin region of southern Transylvania. Glad was said to have authority over the Slavs and Vlachs. The Hungarians sent an army against him, subduing the population between the Morisio (Mureș) and Temes (Timiș) rivers. When they tried to cross the Timiș, Glad attacked them with an army which included Cuman, Bulgarian and Vlach support. The next day, Glad was defeated by the Hungarians. Romanian historiography claims that the Hungarian attack against Glad occurred in 934; however, Hungarian historiography regards him as fictitious. Ahtum was a duke in Banat, and the last ruler who resisted the establishment of the Kingdom of Hungary in the 11th century. He was defeated by Stephen I of Hungary. Ahtum's ethnicity (and that of his people) is controversial; his name is thought to translate "gold" in Old Turkic.

Menumorut is described by Anonymus as duke of the Khazars between the River Tisza and the Ygfon Forest near Ultrasilvania (Transylvania), from the Mureș to the Someș Rivers. He declined the 907 request of the Magyar ruler Árpád to surrender his territory between the Someș and the Meses Mountains. In negotiations with ambassadors Usubuu and Veluc from Árpád he invoked the sovereignty of the Byzantine emperor Leo VI the Wise:

The ambassadors of Árpád crossed the Tisza and came to the capital fortress of Biharia, demanding important territories on the left bank of the river for their duke. Menumorut replied: "Tell Árpád, duke of Hungary, your lord: Indebted we are to him as a friend to a friend, with all requisite to him, since he is a stranger and lacks many. Yet the territory he asked from our good will never will we bestow as long as we will be alive. And we felt sorry that duke Salanus conceded him a very large territory out either of love, which it is said, or out of fear, which is denied. Ourself on the other hand, neither out of love nor out of fear, we will ever concede him land, not even if spanning only a finger, although he said he has a right on it. And his words do not trouble our heart that he stressed he descends from the strain of king Attila, which was called the scourge of God. And if that one raped this country from my ancestor, now thanks to my lord the emperor of Constantinople, nobody can snatch it from my hands."— Gesta Hungarorum

| Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Magyars besieged the citadel of Zotmar (in Romanian Sătmar, in Hungarian Szatmár) and Menumorut's castle in Bihar, defeating him. The Gesta Hungarorum then retells the story of Menumorut. In this version, he married his daughter into the Árpád dynasty. Her son Taksony became ruler of the Magyars and father of Mihály and Géza (whose son Vajk became the first king of Hungary in 1001 under his baptismal name, Stephen).

I.A. Pop confirmed battles between Romanians and Hungarian tribes in the Primary Chronicle.[26] Conflicting theories exist concerning whether or not the Romanized Dacian population (the ancestors of the Romanians) remained in Transylvania after the withdrawal of the Romans (and whether or not Romanians were in Transylvania during the Migration Period, particularly during the Magyar migration). These theories are often used to back competing claims by Hungarian and Romanian nationalists.

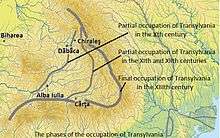

The historian Kurt Horedt dates the entering of the Hungarians in Transylvania in the period between the 10th century and the 13th century. In his theory, the Hungarians conquered Transylvania in five stages:

- 1st stage - around year 900, until Someșul Mic river

- 2nd stage - around year 1000, Someșul Mic valley and the middle and lower course of Mureș river

- 3rd stage - around year 1100, until Târnava Mare river

- 4th stage - around year 1150, until the Olt River line

- 5th stage - around year 1200, until the Carpathian Mountains[27]

As part of the Kingdom of Hungary

High Middle Ages

In 1000 Stephen I of Hungary, grand prince of the Hungarian tribes, was recognised by the Pope and by his brother-in-law Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor as king of Hungary. Although Stephen was raised Roman Catholic and Christianization of the Hungarians was achieved mostly by Rome, he also recognized and supported orthodoxy. Attempts by Stephen to control all Hungarian tribal territories led to wars, including one with his maternal uncle Gyula (a chieftain in Transylvania; Gyula was the second-highest title in the Hungarian tribal confederation).[28] In 1003, Stephen led an army into Transylvania and Gyula surrendered without a fight. This made possible the organization of the Transylvanian Catholic episcopacy (with Gyulafehérvár as its seat), which was finished in 1009 when the bishop of Ostia (as papal legate) visited Stephen and they approved diocesan divisions and boundaries.[29] In 1018 Stephen defeated Ahtum, ruler of the country around the lower Mureș River. According to the Chronicon Pictum, Stephen I also defeated the legendary Kean (a ruler in southern Transylvania of Bulgarians and Slavs).[30]

During the 12th century, the Szeklers were brought to eastern and southeastern Transylvania as border guards. In the 12th and 13th centuries, the areas in the south and northeast were settled by German colonists known as Saxons. Siebenbürgen, (the German name for Transylvania) derives from the seven principal fortified towns founded by these Transylvanian Saxons. The German influence became more marked when, early in the 13th century, King Andrew II of Hungary called on the Teutonic Knights to protect Transylvania in the Burzenland from the Cuman people. After the order expanded its territory beyond Transylvania without authorisation, Andrew expelled the Knights in 1225.

In 1241, Transylvania suffered during the Mongol invasion of Europe. Güyük Khan invaded Transylvania from the Oituz (Ojtoz) Pass, while Subutai attacked in the south from the Mehedia Pass towards Orșova.[31] While Subutai advanced northward to meet Batu Khan, Güyük attacked Hermannstadt/Nagyszeben (Sibiu) to prevent the Transylvanian nobility from aiding King Béla IV of Hungary. Beszterce, Kolozsvár and the Transylvanian Plain region were ravaged by the Mongols, in addition to the Hungarian king's silver mine at Óradna. A separate Mongol force destroyed the western Cumans near the Siret River in the Carpathians and annihilated the Cuman bishopric of Milcov. Estimates of population decline in Transylvania due to the Mongol invasion range from 15 to 50 percent.

The Cumans converted to Roman Catholicism and, after their defeat by the Mongols, sought refuge in central Hungary; Erzsebet, a Cumanian princess, married Stephen V of Hungary in 1254.

Nogai Khan led an invasion of Hungary with Talabuga. He led an army which ravaged Transylvania; cities such as Reghin, Brașov and Bistrița were plundered. Talabuga, who led an army in northern Hungary, was stopped by heavy Carpathian snow; he was defeated near Pest by the royal army of Ladislaus IV and ambushed by the Székely in retreat.

The first written sources of Romanian settlements date to the 13th century; the first cited Romanian township was Olahteluk (1283) in Bihar County.[32][33] The "land of Romanians" (Terram Blacorum)[34][35][36][33] appeared in Fogaras, and this area was mentioned under the name "Olachi" in 1285.[33] The first appearance of a Romanian name (Ola) in Hungary appears in a 1258 charter.[33]

Administration in Transylvania was at the hands of a voivod appointed by the king (the word voivod, or voievod, first appeared in 1193). Before then, the word ispán was used for the chief official of Alba County. Transylvania came under voivod rule after 1263, when the duties of the Counts of Szolnok (Doboka) and Alba were eliminated. The voivod controlled seven comitatus. According to the Chronica Pictum Transylvania's first voivod was Zoltán Erdoelue, a relative of King Stephen.

The three most important 14th-century dignitaries were the voivod, the Bishop of Transylvania and the Abbot of Kolozsmonostor (on the outskirts of present-day Cluj-Napoca). Transylvania was organized according to the estate system. Its estates were privileged groups, or universitates (the central power acknowledged some collective freedoms), with socio-economic and political power; they were also organized using ethnic criteria.

As in the rest of the Hungarian kingdom, the first estate was the aristocracy (lay and ecclesiastic): ethnically heterogeneous, but undergoing homogenization around its Hungarian nucleus. The document granting privileges to the aristocracy was the Golden Bull of 1222, issued by King Andrew II. The other estates were the Saxons, Szeklers and Romanians, all with an ethno-linguistic basis. The Saxons, who had settled in southern Transylvania in the 12th and 13th centuries, were granted privileges in 1224 by the Diploma Andreanum. The Szeklers and Romanians were not regarded as newcomers (colonists) in Transylvania, and were granted partial privileges. While the Szeklers consolidated their privileges, extending them to the entire ethnic group, the Romanians had difficulty retaining their privileges in certain areas (terrae Vlachorum or districtus Valachicales) and lost their estate rank. Nevertheless, when the king (or the voivod) summoned the general assembly of Transylvania (congregatio) during the 13th and 14th centuries it was attended by the four estates: noblemen, Saxons, Szeklers and Romanians (Universis nobilibus, Saxonibus, Syculis et Olachis in partibus Transiluanis).

Later Middle Ages

After 1366, Romanians gradually lost their estate status (Universitas Valachorum) and were excluded from Transylvanian assemblies. The primary reason was religious; during Louis I's proselytization campaign, privileged status was deemed incompatible with schism in a state endowed with an "apostolic mission" by the Holy See. In his 1366 Decree of Turda the king redefined nobility as membership in the Roman Catholic Church, thus excluding the Eastern Orthodox, "schismatic" Romanians. After 1366, nobility was determined not only by ownership of land and people but also by the possession of a royal donation certificate. Since the Romanian social elite—chiefly made up of aldermen (iudices) or knezes (kenezii), who ruled their villages according to the law of the land (ius valachicum)—managed only somewhat to obtain writs of donation and were expropriated. Lacking property or an official status as owner and excluded from privileges as schismatics, the Romanian elite could no longer form an estate and participate in the country's assemblies.

In 1437 Hungarian and Romanian peasants, the petty nobility and burghers from Kolozsvár (Klausenburg, now Cluj), under Antal Nagy de Buda, rose against their feudal masters and proclaimed their own estate (universitas hungarorum et valachorum, "the estate of Hungarians and Romanians"). To suppress the revolt the Hungarian nobility in Transylvania, the Saxon burghers and the Székelys formed the Unio Trium Nationum (Union of the Three Nations): a mutual-aid alliance against the peasants, pledging to defend their privileges against any power except that of Hungary's king. By 1438, the rebellion was crushed. From 1438 onwards the political system was based on the Unio Trium Nationum, and society was regulated by these three estates: the nobility (mostly Hungarians), the Székely and Saxon burghers. These estates, however, were more social and religious than ethnic divisions. Directed against the peasants, the Union limited the number of estates (excluding the Orthodox from political and social life in Transylvania).

Although Eastern Orthodox Romanians were not permitted local self-government like the Székelys and Saxons in Transylvania and the Cumans and Iazyges in Hungary, the Romanian ruling class (nobilis kenezius) had the same rights as the Hungarian nobilis conditionarius. Unlike Maramureș, after the Decree of Turda in Transylvania the only way to remain (or become) nobility was conversion to Roman Catholicism. To preserve their positions, some Romanian families converted to Catholicism and were Magyarized (such as the Hunyadi/Corvinus, Bedőházi, Bilkei, Ilosvai, Drágffy, Dánfi, Rékási, Dobozi, Mutnoki, Dési and Majláth families). Some reached the highest ranks of society; Nicolaus Olahus became Archbishop of Esztergom, while the half-Romanian regent John Hunyadi's son Matthias Corvinus became king of Hungary.

Nevertheless, since the majority of Romanians did not convert to Roman Catholicism there was nowhere for them to be politically represented until the 19th century. They were deprived of their rights and subject to segregation (such as not being allowed to live in or purchase houses in the cities, build stone churches or receive justice. Several examples of legal decisions by the three nations a century after Unio Trium Nationum (1542–1555) are indicative. The Romanian could not appeal for justice against Hungarians and Saxons, but the latter could turn in the Romanian (1552); the Hungarian (Hungarus) accused of robbery could be defended by the oath of the village judge and three honest men, while the Romanian (Valachus) needed the oath of the village knez, four Romanians and three Hungarians (1542); the Hungarian peasant could be punished after being accused by seven trustworthy people, while the Romanian was punished after accusations by only three (1554).

After a diversionary manoeuvre led by Sultan Murad II it was clear that the goal of the Ottomans was not to consolidate their grip on the Balkans and intimidate the Hungarians, but to conquer Hungary. A key figure in Transylvania at this time was John Hunyadi (c. 1387 or 1400–1456). Hunyadi was awarded a number of estates (becoming one of the foremost landowners in Hungarian history) and a seat on the royal council for his service to Sigismund of Luxemburg. After supporting the candidature of Ladislaus III of Poland for the Hungarian throne, he was rewarded in 1440 with the captaincy of the fortress of Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade) and the voivodship of Transylvania (with his fellow voivod Miklos Újlaki). His subsequent military exploits (he is considered one of the foremost generals of the Middle Ages) against the Ottoman Empire brought him further status as the regent of Hungary in 1446 and papal recognition as the Prince of Transylvania in 1448.

Modern era

Early autonomous principality

When the main Hungarian army and King Louis II Jagiello were slain by the Ottomans in the 1526 Battle of Mohács, John Zápolya—voivod of Transylvania, who opposed the succession of Ferdinand of Austria (later Emperor Ferdinand I) to the Hungarian throne—took advantage of his military strength. When John I was elected king of Hungary, another party recognized Ferdinand. In the ensuing struggle Zápolya was supported by Sultan Suleiman I, who (after Zápolya's death in 1540) overran central Hungary to protect Zápolya's son John II. John Zápolya founded the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom (1538–1570), from which the Principality of Transylvania arose. The principality was created after the signing of the 1570 Treaty of Speyer by John Sigismund Zápolya and emperor Maximiliam II. According to the treaty, the Principality of Transylvania nominally remained part of the Kingdom of Hungary.[37]

Habsburg Austria controlled Royal Hungary, which comprised counties along the Austrian border, Upper Hungary and some of northwestern Croatia.[38] The Ottomans annexed central and southern Hungary.[38]

Transylvania became a semi-independent state under the Ottoman Empire (the Principality of Transylvania), where Hungarian princes[39][40][41] who paid the Turks tribute enjoyed relative autonomy[38] and Austrian and Turkish influences vied for supremacy for nearly two centuries. It was now beyond the reach of Catholic religious authority, allowing Lutheran and Calvinist preaching to flourish. In 1563 Giorgio Blandrata was appointed court physician; his radical religious ideas influenced young King John II and Calvinist bishop Francis David, eventually converting both to Unitarianism. Francis David prevailed over Calvinist Peter Melius in a 1568 in public debate, resulting in individual freedom of religious expression under the Edict of Turda (the first such legal guarantee of religious freedom in Christian Europe). Lutherans, Calvinists, Unitarians and Roman Catholics received protection, while the majority Eastern Orthodox Church was tolerated.

Transylvania was governed by princes and its Diet (parliament). The Transylvanian Diet consisted of three estates: the Hungarian elite (largely ethnic Hungarian nobility and clergy), Saxon leaders (German burghers) and the free Székely Hungarians.

The Báthory family, which assumed power at the death of John II in 1571, ruled Transylvania as princes under the Ottomans (and briefly under Habsburg suzerainty) until 1602. The younger Stephen Báthory, a Hungarian Catholic who later became King Stephen Báthory of Poland, tried to maintain the religious liberty granted by the Edict of Turda but interpreted this obligation in an increasingly restricted sense. The late Báthory rule saw Transylvania (under Sigismund Báthory) enter the Long War, which began as a Christian alliance against the Turks and became a four-sided conflict in Transylvania involving the Transylvanians, Habsburgs, Ottomans and the Romanian voivod of Wallachia led by Michael the Brave.

Michael gained control of Transylvania (supported by the Szeklers) in October 1599 after the Battle of Șelimbăr, in which he defeated Andrew Báthory's army. Báthory was killed by Szeklers who hoped to regain their old privileges with Michael's help. In May 1600 Michael gained control of Moldavia, thus he became the leader of the three principalities of Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania (the three major regions of modern Romania). Michael installed Wallachian boyars in certain offices, but did not interfere with the estates and sought support from the Hungarian nobility. In 1600 he was defeated by Giorgio Basta (Captain of Upper Hungary), and lost his Moldavian holdings to the Poles. After presenting his case to Rudolf II in Prague (capital of Germany), Michael was rewarded for his service.[42] He returned, assisting Giorgio Basta in the Battle of Guruslău in 1601. Michael's rule did not last long, however; he was assassinated by Walloon mercenaries under the command of Habsburg general Basta in August 1601. Michael's rule was marred by the pillaging of Wallachian and Serbian mercenaries and Székelys avenging the Szárhegy Bloody Carnival of 1596. When he entered Transylvania he did not grant rights to the Romanian inhabitants. Instead, Michael supported the Hungarian, Szekler, and Saxon nobles by reaffirming their rights and privileges.[43]

After his defeat at Miriszló, the Transylvanian estates swore allegiance to the Habsburg emperor Rudolph. Basta subdued Transylvania in 1604, initiating a reign of terror in which he was authorised to appropriate land belonging to noblemen, Germanize the population and reclaim the principality for Catholicism in the Counter-Reformation. The period between 1601 (the assassination of Michael the Brave) and 1604 (the fall of Basta) was the most difficult for Transylvania since the Mongol invasion. "Misericordia dei quod non-consumti sumus" ("only God's mercy saves us from annihilation") characterised this period, according to an anonymous Saxon writer.

From 1604 to 1606, the Calvinist Bihar magnate István Bocskay led a successful rebellion against Austrian rule. Bocskay was elected Prince of Transylvania April 5, 1603, and Prince of Hungary two months later.

The two major achievements of Bocskay's brief reign (he died December 29, 1606) were the Peace of Vienna (June 23, 1606) and the Peace of Zsitvatorok (November 1606). With the Peace of Vienna Bocskay obtained religious liberty, the restoration of all confiscated estates, repeal of all "unrighteous" judgments, full retroactive amnesty for all Hungarians in Royal Hungary and recognition as independent sovereign prince of an enlarged Transylvania. Almost-equally important was the twenty-year Peace of Zsitvatorok, negotiated by Bocskay between Sultan Ahmed I and Rudolf II.

Gabriel Bethlen (who reigned from 1613 to 1629) thwarted all efforts of the emperor to oppress (or circumvent) his subjects, and won a reputation abroad by championing the Protestant cause. He waged war on the emperor three times, was proclaimed King of Hungary twice and obtained a confirmation of the Treaty of Vienna for the Protestants (and seven additional counties in northern Hungary for himself) in the Peace of Nikolsburg signed December 31, 1621. Bethlen's successor, George I Rákóczi, was equally successful. His principal achievement was the Peace of Linz (September 16, 1645), the last political triumph of Hungarian Protestantism, in which the emperor was forced to reconfirm the articles of the Peace of Vienna. Gabriel Bethlen and George I Rákóczi aided education and culture, and their reign has been called the golden era of Transylvania. They lavished money on their capital Alba Iulia (Gyulafehérvár or Weißenburg), which became the main bulwark of Protestantism in Central Europe. During their reign, Transylvania was one of the few European countries where Roman Catholics, Calvinists, Lutherans and Unitarians lived in mutual tolerance—all officially accepted religions (religiones recaepte). The Orthodox, however, still had inferior atatus.

This golden age (and relative independence) of Transylvania ended with the reign of George II Rákóczi. The prince, coveting the Polish crown, allied with Sweden and invaded Poland in 1657 despite the Ottoman Porte's prohibition of military action. Rákóczi was defeated in Poland and his army taken hostage by the Tatars. Chaotic years followed, with a quick succession of princes fighting one another and Rákóczi unwilling to resign, despite the Turkish threat of military attack. To resolve the political situation, the Turks resorted to military might; invasions of Transylvania with their Crimean Tatar allies, the ensuing loss of territory (particularly their primary Transylvanian stronghold, Várad, in 1660) and diminished manpower led to Prince John Kemény proclaiming the secession of Transylvania from the Ottomans in April 1661 and appealing for help to Vienna. A secret Habsburg-Ottoman agreement, however, prevented the Habsburgs from intervening; Kemény's defeat by the Turks (and the Turkish installation of the weak Mihály Apafi on the throne) marked the subordination of Transylvania, now a client state of the Ottoman Empire.

Habsburg rule

After the defeat of the Ottomans at the Battle of Vienna in 1683, the Habsburgs began to impose their rule on Transylvania. In addition to strengthening the central government and administration, they promoted the Roman Catholic Church as a uniting force and to weaken the influence of Protestant nobility. By creating a conflict between Protestants and Catholics, the Habsburgs hoped to weaken the estates. They also attempted to persuade Orthodox clergymen to join the Uniate (Greek Catholic) Church, which accepted four key points of Catholic doctrine and acknowledged papal authority while retaining Orthodox rituals and traditions. Emperor Leopold I decreed Transylvania's Orthodox Church in union with the Roman Catholic Church by joining the newly created Romanian Greek-Catholic Church. Some priests converted, although the similarity between the two denominations was unclear to many. In response to the Habsburg policy of converting all Romanian Orthodox to Greek-Catholics, several peaceful movements within the Romanian Orthodox population advocated freedom of worship for all Transylvanians; notable leaders were Visarion Sarai, Nicolae Oprea Miclăuș and Sofronie of Cioara.

From 1711 onward, Austrian control over Transylvania was consolidated and Transylvanian princes replaced with Habsburg imperial governors.[44] In 1765 the Grand Principality of Transylvania was proclaimed, consolidating the separate status of Transylvania within the Austrian Empire established by the 1691 Diploma Leopoldinum.[6][9] Hungarian historiography sees this as a formality.[45][46]

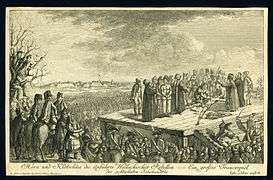

On November 2, 1784, a revolt led by Romanians Vasile Ursu Nicola Horea, Ion Oargă Cloșca and Marcu Giurgiu Crișan began in Hunyad County and spread throughout the Apuseni Mountains. The insurgents' main demands were related to feudal serfdom and the lack of political equality between Romanians and other Transylvanian ethnic groups. They fought at Topánfalva (Topesdorf/Câmpeni), Abrudbánya (Großschlatten/Abrud) and Verespatak (Goldbach/Roșia), defeating the Austrian Imperial Army at Brád (Tannenhof/Brad) on November 27, 1784. The revolt was crushed on February 28, 1785, at Dealul Furcilor (Forks Hill), Alba-Iulia, when the leaders were apprehended. Horea and Cloșca were executed by breaking on the wheel; Crișan hanged himself the night before his execution.

In 1791 the Romanians petitioned Emperor Leopold II for religious equality and recognition as a fourth "nation" in Transylvania (Supplex Libellus Valachorum); the Transylvanian Diet rejected their demands, restoring the Romanians to their marginalised status. In early 1848, the Hungarian Diet took the opportunity presented by revolution to enact a comprehensive program of legislative reform (the April laws), which included a provision for the union of Transylvania and Hungary. Transylvanian Romanians initially welcomed the revolution, believing they would benefit from the reforms. However, their position changed due to the opposition of Transylvanian nobles to reform (such as emancipation of the serfs) and the failure of Hungarian revolutionary leaders to recognise Romanian national interests. In mid-May a Romanian diet at Balázsfalva produced its own revolutionary program, calling for proportional representation of Romanians in the Transylvanian Diet and an end to social and ethnic oppression. The Saxons were concerned about union with Hungary, fearing the loss of their traditional privileges. When the Transylvanian Diet met on May 29, the vote for union was pushed through despite objections from many Saxon deputies. On June 10, the Emperor sanctioned the union vote of the Diet. Military executions and the arrest of revolutionary leaders after the union hardened the Saxons' position. In September 1848, another Romanian assembly in Balázsfalva (Blaj) denounced the union with Hungary and called for an armed uprising in Transylvania. War broke out in November, with Romanian and Saxon troops (under Austrian command) battling Hungarians led by Polish general Józef Bem. Within four months, Bem had ousted the Austrians from Transylvania. However, in June 1849 Tsar Nicholas I of Russia responded to an appeal from Emperor Franz Joseph to send Russian troops into Transylvania. After initial successes against the Russians, Bem's army was defeated decisively at the Battle of Temesvár (Timișoara) on August 9; the surrender of Hungary followed.

The Austrians clearly rejected the October demand that ethnic criteria become the basis for internal borders, with the goal of creating a province for Romanians (Transylvania, alongside Banat and Bukovina); they did not want to replace the threat of Hungarian nationalism with a potential one of Romanian separatism. However, they did not declare themselves hostile to the creation of Romanian administrative offices in Transylvania (which prevented Hungary from including the region in all but name).

The territory was organized into prefecturi (prefectures), with Avram Iancu and Buteanu two prefects in the Apuseni Mountains. Iancu's prefecture, the Auraria Gemina (a name charged with Latin symbolism), became important; it took over from bordering areas which were never fully organized.

Administrative efforts were then halted as Hungarians, under Józef Bem, carried out an offensive through Transylvania. With the covert assistance of Imperial Russian troops, the Austrian army (except for garrisons at Gyulafehérvár and Déva) and the Austrian-Romanian administration retreated to Wallachia and Wallachian Oltenia (both were under Russian occupation). Avram Iancu's remained the only resistance force: he retreated to harsh terrain, mounting a guerrilla campaign on Bem's forces, causing severe damage and blocking the route to Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia). He was, however, challenged by severe shortages: the Romanians had few guns and very little gunpowder. The conflict dragged on for several months, with all Hungarian attempts to seize the mountain stronghold repulsed.

In April 1849, Iancu was approached by Hungarian envoy Ioan Dragoș (a Romanian deputy in the Hungarian Parliament). Dragoș was apparently acting from a desire for peace, and worked to have Romanian leaders meet him in Abrudbánya (Abrud) and listen to the Hungarian demands. Iancu's adversary, Hungarian commander Imre Hatvany, seems to have exploited the provisional armistice to attack the Romanians in Abrudbánya (Abrud). However, Iancu and his men retreated and encircled him.

Hatvany angered the Romanians by having Buteanu captured and murdered. As his position became weaker, he was attacked by Iancu's men until his defeat on May 22. Hatvany and most of his armed group were massacred by their adversaries; Iancu captured their cannons, switching the tactical advantage for the next several months. Lajos Kossuth was angered by Hatvany's gesture (an inspection at the time dismissed all of Hatvany's close collaborators), since it made future negotiations unlikely.

However, the conflict became less harsh: Iancu's men concentrated on seizing local resources and supplies, opting to inflict losses only through skirmishes. The Russian intervention in June precipitated an escalation, since the Poles fighting in the Hungarian revolutionary contingents wanted to resist the Tsarist armies. Henryk Dembiński, a Polish general, negotiated for a truce between Kossuth and the Wallachian émigré revolutionaries. The latter, who were close to Iancu (especially Nicolae Bălcescu, Gheorghe Magheru, Alexandru G. Golescu, and Ion Ghica) wanted to defeat the Russian armies that had crushed their movement in September 1848.

Bălcescu and Kossuth met in May 1849 at Debrecen. The contact has long been celebrated by Romanian Marxist historians and politicians: Karl Marx's condemnation of everything opposing Kossuth led to any Romanian initiative being automatically considered "reactionary". The agreement was not a pact: Kossuth flattered the Wallachians, encouraging them to persuade Iancu's armies leaving Transylvania to help Bălcescu in Bucharest. While agreeing to mediate for peace, Bălcescu never presented these terms to the fighters in the Apuseni Mountains. All Iancu agreed to was his forces' neutrality in the conflict between Russia and Hungary. Thus, he secured his position as the Hungarian armies suffered defeats in July (culminating in the Battle of Segesvár) and capitulated on August 13.

After quashing the revolution, Austria imposed a repressive regime on Hungary and ruled Transylvania directly through a military governor, with German the official language. Austria abolished the Union of Three Nations, granting citizenship to the Romanians. Although the former serfs were given land by the Austrian authorities, it was often barely sufficient for subsistence living. These poor conditions caused many Romanian families to cross into Wallachia and Moldavia, searching for better lives.

Austro-Hungarian Empire

Due to external and internal problems, reforms seemed inevitable to secure the integrity of the Habsburg Empire. Major Austrian military defeats (such as the 1866 Battle of Königgrätz) forced Austrian emperor Franz Joseph to concede internal reforms. To appease Hungarian separatism, the emperor made a deal with Hungary (the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, negotiated by Ferenc Deák) by which the dual monarchy of Austria–Hungary came into existence. The two realms were governed separately by two parliaments from two capitals, with a common monarch and common external and military policies. Economically, the empire was a customs union. The first prime minister of Hungary after the Compromise was Count Gyula Andrássy. The old Hungarian Constitution was restored, and Franz Joseph was crowned as King of Hungary.

The era saw considerable economic development, with the GNP per capita growing roughly 1.45 percent annually from 1870 to 1913. That level of growth compared favorably with that of other European nations, such as Britain (1.00 percent), France (1.06 percent), and Germany (1.51 percent). Technological growth accelerated industrialization and urbanization. Many state institutions and the modern administrative system of Hungary were established during this period. However, as a result of the Compromise the special status of Transylvania ended; it became a province under the Hungarian diet. While part of Austria-Hungary, Transylvania's Romanians were oppressed by the Hungarian administration through Magyarization;[47][48] German Saxons were also subject to this policy. During this time, Hungarian-administered Transylvania consisted of a 15-county (Hungarian: megye) region, covering 54,400 km² in the southeast of the former Kingdom of Hungary. The Hungarian counties at the time were Alsó-Fehér, Beszterce-Naszód, Brassó, Csík, Fogaras, Háromszék, Hunyad, Kis-Küküllő, Kolozs, Maros-Torda, Nagy-Küküllő, Szeben, Szolnok-Doboka, Torda-Aranyos, and Udvarhely.

Part of Romania

Greater Romania

Although Kings Carol I and Ferdinand I were from the German Hohenzollern dynasty, the Kingdom of Romania refused to join the Central Powers and remained neutral at the outbreak of World War I. In 1916 Romania joined the Triple Entente by signing a secret military convention recognising Romania's rights over Transylvania. King Ferdinand's wife, Marie (who had British and Russian parentage) was highly influential during these years.[49]

As a consequence of the convention, Romania declared war against the Central Powers on August 27, 1916, and crossed the Carpathian mountains into Transylvania; this forced the Central Powers to fight on another front. A German-Bulgarian counter-offensive began the following month in Dobruja and in the Carpathians, driving the Romanian army back into Romania by mid-October and eventually leading to the capture of Bucharest. The exit of Russia from the war in March 1918 with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk left Romania alone in Eastern Europe, and a peace treaty between Romania and Germany was negotiated in May 1918. By mid-1918 the Central Powers were losing the war on the Western Front, and the Austro-Hungarian empire had begun to disintegrate. Austria-Hungary signed a general armistice in Padua on November 3, 1918; the nations inside Austria-Hungary proclaimed their independence from the empire during September and October of that year.

After World War I

In 1918, as a result of the German defeat in World War I the Austro-Hungarian monarchy collapsed. On October 31, the successful Aster Revolution in Budapest brought the left liberal, pro-Entente count Mihály Károlyi to power as prime minister of Hungary. Influenced by Woodrow Wilson's pacifism, Károlyi ordered the disarmament of Hungarian Army. The Károlyi government outlawed all Hungarian armed associations and proposals intending to defend the country.

The resulting Treaty of Bucharest was denounced in October 1918 by the Romanian government, which then re-entered the war on the Allied side and advanced to the Mureș (Maros) river in Transylvania.

The leaders of Transylvania's National Party met and drafted a resolution invoking the right of self-determination (influenced by Woodrow Wilson's 14 points) for Transylvania's Romanian people, and proclaimed the unification of Transylvania with Romania. In November the Romanian National Central Council, representing all Romanians in Transylvania, notified the Budapest government that it would take control of twenty-three Transylvanian counties (and parts of three others) and requested a Hungarian response by November 2. The Hungarian government (after negotiations with the council) rejected the proposal, claiming that it failed to secure the rights of the ethnic Hungarian and German populations. In Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia) on December 1, a mass assembly of ethnic Romanians passed a resolution calling for the unification of all Romanians in a single state. The National Council of Transylvanian Germans and the Council of the Danube Swabians from the Banat approved the proclamation on 8 January 1919. In response, the Hungarian General Assembly of Kolozsvár (Cluj) reaffirmed the loyalty of Hungarians from Transylvania to Hungary on December 22, 1918.

The Romanian Army, representing the Entente powers, entered Transylvania from the east on November 12, 1918. In December they entered southern Transylvania, crossed the demarcation line on the Maros (Mureș) river by mid-December and advanced to Kolozsvár (Cluj) and Máramarossziget (Sighet) after making a request to the Powers of Versailles to protect the Romanians in Transylvania. In February 1919, to prevent armed clashes between Romanian and withdrawing Hungarian troops, a neutral zone was created.

The prime minister of the newly proclaimed Republic of Hungary resigned in March 1919, refusing the territorial concessions (including Transylvania) demanded by the Entente. When the Communist Party of Hungary (led by Béla Kun) came to power in March 1919, it proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic; after promising that Hungary would regain the lands under its control during the Austro-Hungarian Empire it attacked Czechoslovakia and Romania, leading to the Hungarian-Romanian War of 1919. The Hungarian army began an April 1919 offensive in Transylvania along the Someș (Szamos) and Maros rivers. A Romanian counter-offensive pushed forward to reach the Tisza River in May. Another Hungarian offensive in July penetrated 60 km into Romanian lines before a further Romanian counter-offensive led to the end of Hungarian Soviet Republic and after the occupation of Budapest. The Romanian army withdrew from Hungary between October 1919 and March 1920.

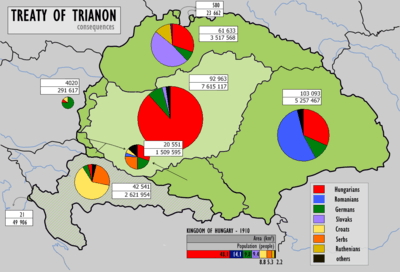

The Treaty of Versailles, formally signed in June 1919, recognised the sovereignty of Romania over Transylvania. The Treaties of St. Germain (1919) and Trianon (June 1920) further defined the status of Transylvania and the new border between the states of Hungary and Romania. King Ferdinand I of Romania and Queen Maria of Romania were crowned at Alba Iulia in 1922.

România Mare ("Great Romania") refers to the Romanian state between the First and Second World Wars. Romania reached its greatest territorial extent, uniting almost all historical Romanian lands (except northern Maramureș, Western Banat and small areas of Partium and Crișana). Great Romania was an ideal of Romanian nationalism.

At the end of World War I Transylvania and Bessarabia were united with the Romanian Old Kingdom, the Deputies of Transylvanian Romanians declared the union of Transylvania with Romania in Alba Iulia on 1. December 1918.; Bessarabia, having declared independence from Russia in 1917 at the Conference of the Country (Sfatul Țării), called in Romanian troops to protect the province from the Bolsheviks. The union of the Transylvania, Maramureș, Crișana and Banat regions with the Old Kingdom of Romania was ratified in 1920 by the Treaty of Trianon, which recognised the sovereignty of Romania over these regions and settled the border between the Republic of Hungary and the Kingdom of Romania. The union of Bukovina and Bessarabia with Romania was ratified in 1920 by the Treaty of Versailles. Romania had also acquired Southern Dobrudja from Bulgaria as a result of its victory in the Second Balkan War in 1913.

World War II and Communist era

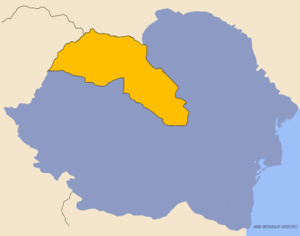

In August 1940, during the Second World War, the northern half of Transylvania (Northern Transylvania) was annexed to Hungary by the second Second Vienna Award. On March 19, 1944, following the occupation of Hungary by the Nazi Germany army through Operation Margarethe, Northern Transylvania came under German military occupation. After King Michael's Coup, Romania left the Axis and joined the Allies, and, as such, fought together with the Soviet army against Nazi Germany, regaining Northern Transylvania. The Second Vienna Award was voided by the Allied Commission through the Armistice Agreement with Romania (September 12, 1944) whose Article 19 stipulated the following: "The Allied Governments regard the decision of the Vienna award regarding Transylvania as and void and are agreed that Transylvania the greater part thereof) should be returned to Rumania, subject to confirmation at the peace settlement, and the Soviet Government agrees that Soviet forces shall take part for this purpose in joint military operations with Rumania against Germany and Hungary." The 1947 Treaty of Paris reaffirmed the borders between Romania and Hungary, as originally defined in Treaty of Trianon, 27 years earlier, thus confirming the return of Northern Transylvania to Romania.[50] From 1947 to 1989, Transylvania, as the rest of Romania, was under a communist regime.

Present

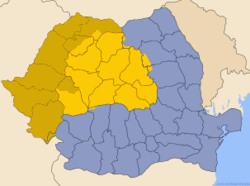

Today, "Transylvania proper" is included within the Romanian counties (județe) of Alba, Bistrița-Năsăud, Brașov, Cluj, Covasna, Harghita, Hunedoara, Mureș, Sălaj and Sibiu. In addition to Transylvania proper, modern Transylvania includes Crișana and part of the Banat; these regions are in the counties of Arad, Bihor, Caraș-Severin, Maramureș, Sălaj, Satu Mare and Timiș.

Demographics and historical research

According to Jean W. Sedlar, the Vlachs may have comprised two-thirds of Transylvania's population in 1241 on the eve of the Mongol invasion.[51]

According to an investigation based on place-names, 511 villages of Transylvania and Banat appear in documents at the end of the 13th century, however only 3 of them bore Romanian names.[52] Around 1400 AD, Transylvania and Banat consisted of 1757 villages, though only 76 (4.3%) of them had names of Romanian origin.[52]

Pope Pius II affirmed in the 15th century that Transylvania was populated by three races: the Germans, Székelys, and Vlachs.[53]

Antun Vrančić wrote that Transylvania "is inhabited by three nations – Székelys, Hungarians and Saxons. I should add the Romanians who – even though they easily equal any of the others in number – have no liberties, no nobility and no rights of their own, except for a small number living in the district of Hațeg, where it is believed that the capital of Decebalus lay, and who were made nobles during the time of John Hunyadi, a native of that place, because they always took part tirelessly in the battles against the Turks".[54]

According to George W. White, in 1600 the Romanian inhabitants were primarily peasants, comprising more than 60 percent of the population.[55]

Around 1650, Vasile Lupu in a letter written to the Sultan attests that the number of Romanians are already more than the one-third of the population.[56]

In Benedek Jancsó's estimation there were 150,000 Hungarians, 100,000 Saxons and 250,000 Romanians in Transylvania at the beginning of the 18th century.[57] Official censuses with information on Transylvania's ethnic composition have been conducted since the 18th century. On May 1, 1784, Joseph II called for a census of the empire, including Transylvania. The data were published in 1787; however, this census showed only the overall population.[58] Fényes Elek, a 19th-century Hungarian statistician, estimated in 1842 that in Transylvania between 1830 and 1840 62.3 percent were Romanians and 23.3 percent Hungarians.[59] The first official census in Transylvania distinguishing nationalities (by mother tongue) was conducted by Austro-Hungarian authorities in 1869.

The data recorded in all censuses is presented in the table below. The census system in Hungary between 1880 and 1910 was based on native language. Before 1880, Jews were counted as an ethnic group; later, they were counted according to their first language.

| Year | Total | Romanians | Hungarians | Germans | Székelys | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1241a | - | ~66% | - | On the eve of the Mongol invasion. Estimation by Jean W.Sedlar | ||

| 1301-1308a | 349,000 | 5.1% | 88.8% (with Székelys) | 6.0% | - | Estimation by Tamás Lajos based on the List of Papal Tithes from 1332-1337[60]

|

| 1495a | 454,000 | 22%[61] | 55,2% (with Székelys)[61] | 22%[61] | - | Estimation by Károly Kocsis & Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi |

| 1500a | - | 24% | 47% | 16% | 13% | Estimation by Elemér Mályusz (1898 - 1989) |

| 1551 | - | >25% | <=25% | <=25% | <=25% | Estimation[62] by Károly Nyárády R. based on Antun Vrančić's work[63] |

| 1571a | 955,000 | 29.3% | 52.3% | 9.4% | - | Estimation[64] |

| 1595a | 670,000 | ~28.4%[61] | 52,2%[61] | 18,8%[61] | - | Estimation by Károly Kocsis & Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi |

| 1600a | - | ~60% | - | - | Estimation by George W. White | |

| 1650a | - | > ~33,33% | - | - | Estimation by Vasile Lupu[65] | |

| 1700a | ~500,000 | ~50% | ~30% | ~20% | - | Estimation by Benedek Jancsó (1854 - 1930) |

| 1700 | ~800,000–865,000 | - | Recent estimates[66] | |||

| 1712-1713 | ~34% | ~47% | ~19% | - | An official estimate by the Verwaltungsgericht (Austrian administrative authority) from 1712-1713[66] | |

| 1720a | 806,221 | 49,6%[61] | 37,2%[61] | 12,2%[61] | - | Estimation by Károly Kocsis & Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi |

| 1721 | - | 48,28% | 36.09% | 15.62% | - | Estimation by Ignác Acsády[67] |

| 1730a | ~725,000 | 57.9% | 26.2% | 15.1% | - | Austrian statistics |

| 1765a | ~1,000,000 | 55.9% | 26% | 12% | - | Estimation by Bálint Hóman and Gyula Szekfü (1883 - 1955) |

| 1773a[68] | 1,066,017 | 63.5% | 24.2% | 12.3% | - | |

| 1784a | 1,440,986 | - | - | - | - | |

| 1790a[69] | 1,465,000 | 50.8% | 30.4% | - | - | |

| 1835a | - | 62.3% | 23.3% | - | - | |

| 1850a | 2,073,372 | 59.1% | 25.9% | 9.3% | - | |

| 1850a | 1,823,212 | 57.2% | 26.7% | 10.5% | - | 1850/51. census[70] |

| 1869 | 4,224,436 | 59.0% | 24.9% | 11.9% | - | Hungarian population census |

| 1880 | 4,032,851 | 57.0% | 25.9% | 12.5% | - | Hungarian population census |

| 1890 | 4,429,564 | 56.0% | 27.1% | 12.5% | - | Hungarian population census |

| 1900 | 4,840,722 | 55.2% | 29.4% | 11.9% | - | Hungarian population census |

| 1910 | 5,262,495 | 53.8% | 31.6% | 10.7% | - | Hungarian population census |

| 1919 | 5,259,918 | 57.1% | 26.5% | 9.8% | - | Romanian population census |

| 1920 | 5,208,345 | 57.3% | 25.5% | 10.6% | - | Romanian population census |

| 1930 | 5,114,214 | 58.3% | 26.7% | 9.7% | - | Romanian population census |

| 1941 | 5,548,363 | 55.9% | 29.5% | 9.0% | - | Romanian population census |

| 1948 | 5,761,127 | 65.1% | 25.7% | 5.8% | - | Romanian population census |

| 1956 | 6,232,312 | 65.5% | 25.9% | 6.0% | - | Romanian population census |

| 1966 | 6,736,046 | 68.0% | 24.2% | 5.6% | - | Romanian population census |

| 1977 | 7,500,229 | 69.4% | 22.6% | 4.6% | - | Romanian population census |

| 1992 | 7,723,313 | 75.3% | 21.0% | 1.2% | - | Romanian population census |

| 2002 | 7,221,733 | 74.7% | 19.6% | 0.7% | - | Romanian population census |

| 2011 | 6,789,250 | 70.6% | 17.9% | 0.4% | - | Romanian population census |

Note: a The data from 1301-1308, 1700 (Benedek Jancsó's estimation) 1730 (Austrian statistics), 1765 (Hóman and Szekfü record)[75] and the 1850 census refer to Transylvania proper only: the counties, districts and regions of Belső-Szolnok County, Beszterce County, Doboka County, Fehér County, Fogarasföld, Hátszegvidék, Hunyad County, Királyföld, Kolozs County, Küküllő County, Székely Land and Torda County. It therefore excludes the data from the counties of Arad County, Bihar County, Krassó County, Máramaros County, Szatmár County, Szörény County and Temes County.

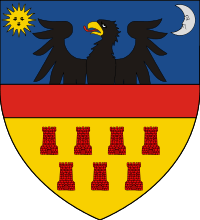

Coat of arms

The Transylvanian coat of arms depicts:

- An eagle on a blue background, representing medieval nobility (primarily Magyar)

- Sun and crescent moon, representing the Szeklers

- Seven red towers on a yellow background, representing the seven castles of the Transylvanian Saxons

These symbols (representing the three Transylvanian estates) had been in use (usually with the Hungarian coat of arms) since the 16th century because Transylvanian princes maintained their claims to the throne of the Kingdom of Hungary. The Diet of 1659 codified the coat of arms. While the Hungarians, Saxons and Szeklers are represented the Romanians are not, despite their proposal to include a representation of Dacia.

Regions are not legal administrative units in Romania; consequently, the coat of arms is only used within the coat of arms of Romania. This officially recognised image is based on the 1659 symbols, and includes the traditional Transylvania estates.

Another, short-lived heraldic representation of Transylvania is found on the coat of arms of Michael the Brave. Besides the Wallachian eagle and the Moldavian aurochs, Transylvania is represented by two lions holding a sword (referring to the Dacian Kingdom) standing on seven hills.

The 1848 revolutionary movement proposed a revision to the Transylvanian coat of arms, with representation of the Romanian majority. To the 1659 representation it introduced a central section, portraying a Dacian woman (symbolizing the Romanian nation) holding in her right hand a sickle and in her left a Roman legion's flag with the initials "D.F." (Dacia Felix). On the woman's right there was an eagle with a laurel crown in its beak, and on its left side a lion. This representation of the Romanian nation was inspired by a coin issued by the Roman emperor Marcus Julius Philippus at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa to honor the province of Dacia.

Historiography

The history of Transylvania has been subject to disagreement between national narratives, especially those of Romania and Hungary. In November 2006, a Romanian newspaper reported on a project for a book on the history of Transylvania under the joint auspices of the Romanian Academy and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.[76]

See also

- Prehistory of Transylvania

- The Ancient History of Transylvania

- History of Romania

- History of Cluj-Napoca

- History of Hungary

- Kingdom of Hungary in the Middle Ages

- List of Transylvanian rulers

- History of the Székely people

- Aftermath of World War I

- Austria-Hungary

- Celts in Transylvania

- Dacia

- National awakening of Romania

- Origin of the Romanians

- Transylvanian School

- Avram Iancu

References

- ↑ Istvan Lazar: Transylvania: A Short History, Simon Publications, 1997

- ↑ Dennis P. Hupchick, Conflict and chaos in Eastern Europe, Palgrave Macmillan, 1995, p. 62

- ↑ Peter F. Sugar, Southeastern Europe under Ottoman rule, 1354–1804, University of Washington Press, 1993, pp. 150–154

- ↑

- ↑ Peter F. Sugar. "Southeastern Europe Under Ottoman Rule, 1354–1804" (History of East Central Europe), University of Washington Press, July 1983, page 163

- 1 2 Paul Lendvai, Ann Major. The Hungarians: A Thousand Years of Victory in Defeat C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2003, page 146;

- ↑

- ↑ "Transylvania" (2009). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 7, 2009

- 1 2 "Diploma Leopoldinum" (2009). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 7, 2009

- ↑ John F. Cadzow, Andrew Ludanyi, Louis J. Elteto, Transylvania: The Roots of Ethnic Conflict, Kent State University Press, 1983, page 79

- ↑ James Minahan: One Europe, many nations: a historical dictionary of European national groups, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT 06991

- ↑ Population census of 2002 (Romanian) – recensamant 2002 --> rezultate --> 4. POPULATIA DUPA ETNIE

- ↑ Gündisch, Konrad (1998). Siebenbürgen und die Siebenbürger Sachsen. Langen Müller. ISBN 3-7844-2685-9.

- ↑ Lendering, Jona. "Herodotus of Halicarnassus". Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The history of Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons, by Dr. Konrad Gündisch

- ↑ Bóna, István; Translation by Péter Szaffkó (2001). The Settlement of Transylvania in the 10th and 11th Centuries. Columbia University Press, New York, ,. ISBN 0-88033-479-7.

- ↑ Kosáry Domokos, Bevezetés a magyar történelem forrásaiba és irodalmába 1, p. 29

- ↑ Peter F. Sugar, Péter Hanák, Tibor Frank, A History of Hungary, Indiana University Press, 1994, p.11

- ↑ The shorter Cambridge medieval history by Charles William Previté-Orton p.739 &q&f=false

- ↑ Béla Köpeczi,History of Transylvania, Volume 2, Social Science Monographs, 2001, p. 341-344-357

- ↑ Madgearu, Alexandru (2001). Românii în opera Notarului Anonim. Cluj-Napoca: Centrul de Studii Transilvane, Fundația Culturală Română. ISBN 973-577-249-3.

- 1 2 Bóna, István (2001). "II. From Dacia to Erdoelve: Transylvania in the Period of the Great Migrations (271–896)". In Köpeczi, Béla. History of Transylvania. Volume I. From the Beginnings to 1606. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Madgearu, Alexandru (1999–2002). "Were the Zupans Really Rulers of Some Romanian Early Medieval Polities?" (PDF). Revista de Istorie Socială. 4–7: 15–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 27, 2009.

- ↑ I.M.Țiplic, Considerații cu privire la liniile întărite de tipul prisacilor din Transilvania, Acta Terrae Septemcastrensis I, p. 147-164

- ↑ http://groznijat.tripod.com/thrac/thrac_8.html

- ↑ Ioan Aurel Pop, Din mainile vlahilor schismatici, Editura Litera, bucuresti,2011,p.43

- ↑ http://www.bjmures.ro/bdPublicatii/CarteStudenti/P/AurelPop-Istoria_Transilvaniei.pdf

- ↑ "Gyula and the Gyulas". History Institute, Hungarian Academy of Sciences History of Transylvania, vol. 1. p. 382. Archived from the original (book) on January 4, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ↑ http://restromania.com/Sociologie/TheHistoryOfTransilvania_1000-1900.htm

- ↑ (Hungarian) Körösladány Online

- ↑ Chambers, James. The Devil's Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe. Atheneum. New York. 1979. ISBN 0-689-10942-3

- ↑ György Fejér, Codex diplomaticus Hungariae ecclesiasticus ac civilis, Volume 7, typis typogr. Regiae Vniversitatis Vngaricae, 1831

- 1 2 3 4 Tamás Kis, Magyar nyelvjárások, Volumes 18–21, Nyelvtudományi Intézet, Kossuth Lajos Tudományegyetem (University of Kossuth Lajos). Magyar Nyelvtudományi Tanszék, 1972, p. 83 </

- ↑ Dennis P. Hupchick, Conflict and chaos in Eastern Europe, Palgrave Macmillan, 1995 p. 58

- ↑ István Vásáry, Cumans and Tatars: Oriental military in the pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365, Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 28

- ↑ Heinz Stoob, Die Mittelalterliche Städtebildung im südöstlichen Europa, Böhlau, 1977, p. 204

- ↑ Anthony Endrey, The Holy Crown of Hungary, Hungarian Institute, 1978, p. 70

- 1 2 3 A Country Study: Hungary. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0-16-029202-6. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- ↑ Helmut David Baer (2006). The struggle of Hungarian Lutherans under communism. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-1-58544-480-9. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

- ↑ Eric Roman (2003). Austria-Hungary & the successor states: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present. Infobase Publishing. pp. 574–. ISBN 978-0-8160-4537-2. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

- ↑ J. Atticus Ryan; Christopher A. Mullen (1998). Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization: yearbook. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-90-411-1022-0. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.amazon.de/dp/B002975CP0

- ↑ George W. White, Nationalism and territory, 2000, p.132

- ↑ http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Grand+Principality+of+Transylvania

- ↑ "JOHN HUNYADI: Hungary in American History Textbooks". Andrew L. Simon. Corvinus LIbrary Hungarian History. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ↑ The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia Copyright 2007, Columbia University Press. Licensed from Columbia University Press. All rights reserved. www.cc.columbia.edu/cu/cup/

- ↑ András Gerő, James Patterson, Enikő Koncz: Modern Hungarian society in the making: the unfinished experience, pp. 214, Oxford University Press, USA, 1995

- ↑ R.Bideleux and Ia. Jeffries: A history of Eastern Europe: crisis and change, pp. 30ff. Routledge, NY, USA, 1998

- ↑ Easterman, Alexander (1942). King Carol, Hitler, and Lupescu. Victor Gollancz Ltd., London.

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/place/Transylv

- ↑ East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500, by Jean W.Sedlar p.8

- 1 2 Louis L. Lote (editor), ONE LAND — TWO NATIONS TRANSYLVANIA AND THE THEORY OF DACO-ROMAN-RUMANIAN CONTINUITY, COMMITTEE OF TRANSYLVANIA INC. (This is a special issue of the CARPATHIAN OBSERVER Volume 8, Number 1. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number; 80-81573), 1980, p. 10

- ↑ Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini: Europe (ch. 2.14.), p. 64.

- ↑ Pop, Ioan-Aurel (2006). Romanians in the 14th–16th Centuries: From the “Christian Republic” to the “Restoration of Dacia”, In: Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (2005); History of Romania: Compendium; Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies), p.304, ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4

- ↑ George W. White, ''Nationalism and territory, 2000, p.132

- ↑ Sándor Szilágyi: Erdély és az északkeleti háború. Levelek és okiratok Bp. 1890 I. 246-247, 255-256 - Sándor Szilágyi: Transilvania and the north-eastern war. Letters and documents Bp. 1890 p. 246-247, 255-256

- ↑ http://mek.niif.hu/03400/03407/html/280.html

- ↑ http://www.hungarian-history.hu/lib/transy/transy03.htm

- ↑ Elek Fényes, Magyarország statistikája, Vol. 1, Trattner-Károlyi, Pest. VII, 1842

- ↑ Tamás Lajos: Rómaiak, románok és Vlachok Dacia Trajánában Bp. 1935. 42. o. - Lajos Tamás: Romans, Romanians and Vlachs in Dacia Traiana 1935 Bp. p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Károly Kocsis, Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi, Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin, Simon Publications LLC, 1998, p. 102 (Table 19)

- ↑ Nyárády R. Károly - Erdély népesedéstörténete c. kéziratos munkájábol. Megjelent: A Központi Statisztikai Hivatal Népességtudományi Kutató Intézetenek történeti demográfiai füzetei. 3. sz. Budapest, 1987. 7-55. p., Erdélyi Múzeum. LIX, 1997. 1–2. füz. 1-39. p.

- ↑ Antonius Wrancius: Expeditionis Solymani in Moldaviam et Transsylvaniam libri duo. De situ Transsylvaniae, Moldaviae et Transalpinae liber tertius.

- ↑ Erdély rövid története, Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1989, 238. o. - The short history of Transylvania, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1989 Budapest p. 238

- ↑ Sándor Szilágyi: Erdély és az északkeleti háború. Levelek és okiratok Bp. 1890 I. 246-247, 255-256 - Sándor Szilágyi: Transylvania and the northeastern war. Letters and documents Bp. 1890 p. 246-247, 255-256

- 1 2 Trócsányi, Zsolt (2002). A NEW REGIME AND AN ALTERED ETHNIC PATTERN (1711–1770) (Demographics), In: Béla Köpeczi, HISTORY OF TRANSYLVANIA Volume II. From 1606 to 1830, Columbia University Press, New York, 2002, p. 2 - 522/531, ISBN 0-88033-491-6

- ↑ Acsády Ignác: Magyarország népessége a Pragamtica Sanctio korában, Magyar statisztikai közlemények 12. kötet - Ignác Acsády: The population of Hungary in the ages of the Pragmatica Sanction, Magyar statisztikai közlemények vol. 12.

- ↑

- ↑ Peter Rokai – Zoltan Đere – Tibor Pal – Aleksandar Kasaš, Istorija Mađara, Beograd, 2002, pages 376–377.

- ↑ Erdély rövid története, Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1989, 371. o. - The short history of Transylvania, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1989 Budapest p. 371.

- ↑ Árpád Varga E., Hungarians in Transylvania between 1870 and 1995, Original title: Erdély magyar népessége 1870–1995 között, Magyar Kisebbség 3–4, 1998 (New series IV), pp. 331–407. Translation by Tamás Sályi, Teleki László Foundation, Budapest, 1999

- ↑ Rudolf Poledna, François Ruegg, Cǎlin Rus, Interculturalitate, Presa Universitarǎ Clujeanǎ, Cluj-Napoca, 2002. p. 160.

- ↑ Erdély etnikai és felekezeti statisztikája (1850–1992). Retrieved 2007-05-17

- ↑ Erdély népességének etnikai és vallási tagolódása a magyar államalapítástól a dualizmus koráig

- ↑ http://www.hungarian-history.hu/lib/minor/min01.htm

- ↑ Delia Budurca, Magda Crisan, România și Ungaria rescriu istoria Ardealului ("Romania and Hungary rewrite the history of Transylvania"), Adevărul, November 16, 2006.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Transylvania. |

.svg.png)