Multiplexed Analogue Components

.jpg)

Multiplexed analogue components (MAC) was a satellite television transmission standard, originally proposed for use on a Europe-wide terrestrial HDTV system, although it was never used terrestrially.

Technical overview

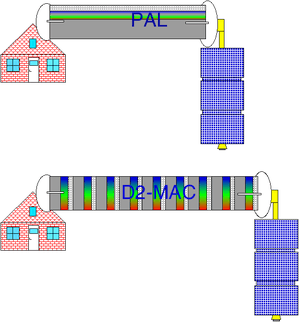

MAC transmits luminance and chrominance data separately in time rather than separately in frequency (as other analog television formats do, such as composite video).

Audio and scrambling (selective access)

- Audio, in a format similar to NICAM was transmitted digitally rather than as an FM sub-carrier.

- The MAC standard included a standard scrambling system, EuroCrypt, a precursor to the standard DVB-CSA encryption system

History

MAC was originally developed by the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA) (dates unknown) in the UK for delivering high quality pictures via direct broadcast satellites that would be independent of European countries' choice of terrestrial colour-coding standard.[1]

Variants

A number of broadcasting variants of the MAC standard exist.

- A-MAC designed as a test-bed for the MAC concept. A-MAC was never deployed by any broadcaster. S-MAC is design descendant A-MAC.

- B-MAC used in South Africa by Multichoice, Australia by Optus and also used in parts of Asia until 2005 when digital compression finally replaced B-MAC.

- C-MAC has a wide-screen backwardly compatible variant called E-MAC.

- D-MAC (used by British Satellite Broadcasting) but not used on cable systems. This is a satellite only MAC format. Also used by NRK. This because D-MAC has 4 audio channels (D2-MAC just has 2 audio channels). Then it was possible to transmit 3 radio channels and 1 TV channel at one D-MAC channel.

- D2-MAC used until July 2006 in Scandinavia and until the mid-1990s for German and French satellite television. Some cable systems may still be using D2-MAC in Europe and Asia.

- HD-MAC, an early high-definition television standard allowing for 2048x1152 resolution.

Studio (non-broadcast) MAC variants

S-MAC (Studio MAC): Used mostly in North America.

- Processing NTSC component signals yields better results (a higher quality image) than manipulating NTSC directly – thus the need to create S-MAC.

- It is not possible to mix standard MAC signals in the studio environment because the (R-Y) and (B-Y) components are carried on alternate lines.

- S-MAC's SECAM like approach to bandwidth reduction is technical annoyance, but most studio users are not affected by it.

- In S-MAC the luminance is compressed by 2:1 and the two chrominance signals by 4:1 so that all three may occupy the same line.

- S-MAC's vision bandwidth is 11 MHz, only ~2.8x that of NTSC's vision bandwidth of 4.2 MHz.

- S-MAC can be carried on a single circuit and converted losslessly to and from C-MAC at any stage.

- S-MAC is well suited for SNG applications (AKA: news gathering trucks).

MAC system innovations

Mathematical

- A-MAC proved the mathematical principle that separating vision from colour for TV transmission was technologically viable.

Broadcast engineering

- The MAC audio subsystem is very similar to NICAM, so much so that identical chip-sets are used.

Broadcast engineering

- D-MAC satellite broadcasts provided the first broadcast sourced wide-screen television in Europe, and HD-MAC provided the first HDTV broadcasts, in 1992.

Technical challenges

Although the MAC technique is capable of superior video quality, (similar to the improvement of component video over composite in a DVD player), its major drawback was that this quality was only ever realized when the video signals being transmitted remained in component form from source to transmitter. If at any stage the video had to be handled in composite form, the necessary encoding/decoding processes would severely degrade the picture quality.

- Terrestrial TV broadcasters were never able to take full advantage of MAC image quality due to multiple interactions between their composite and component signal paths.

- Direct to Home and TVRO broadcasters were able to take advantage of MAC's improved image quality because their studios and routing facilities were far less complex.

- The success of NICAM audio for terrestrial television can be traced to the success of MAC technology. The MAC audio subsystem is nearly identical in design and function to NICAM.

Technological obsolescence

Since the vast majority of TV stations and similar installations were only wired for composite video, the fitting of a MAC transmitter at the end of the chain had the effect of degrading the transmitted image quality, rather than improving it.

For this and other technical reasons, MAC systems never really caught on with broadcasters. MAC transmission technology was made obsolete by the radically new digital systems (like DVB-T and ATSC) in the late 1990s.

Although MAC transmission systems are still used, the technology is obsolete. It is expected that MAC will cease to be used for TV transmission by 2012.

See also

TV transmission systems:

- Analog high-definition television systems

- PAL, what MAC technology tried to replace

- SECAM, what MAC technology tried to replace

- DVB-S, MAC technology was replaced by this standard

- DVB-T, MAC technology was replaced by this standard

References

External links

- Multiplexed Analogue Components in "Analog TV Broadcast Systems" by Paul Schlyter