N-linked glycosylation

N-linked glycosylation, is the attachment of the sugar molecule oligosaccharide known as glycan to a nitrogen atom (amide nitrogen of asparagine (Asn) residue of a protein), in a process called N-glycosylation, studied in biochemistry.[1] This type of linkage is important for both the structure[2] and function[3] of some eukaryotic proteins. The N-linked glycosylation process occurs in eukaryotes and widely in archaea, but very rarely in bacteria. The nature of N-linked glycans attached to a glycoprotein is determined by the protein and the cell in which it is expressed.[4] It also varies across species. Different species synthesize different types of N-linked glycan.

Bond formation and energetics

There are two types of bonds involved in a glycoprotein: bonds between the saccharides residues in the glycan and the linkage between the glycan chain and the protein molecule.

The sugar moieties are linked to one another in the glycan chain via glycosidic bonds. These bonds are typically formed between carbon 1 and 4 of the sugar molecules. The formation of glycosidic bond is energetically unfavourable, therefore the reaction is coupled to the hydrolysis of two ATP molecules.[4]

On the other hand, the attachment of a glycan residue to a protein requires the recognition of a consensus sequence. N-linked glycans are almost always attached to the nitrogen atom of an asparagine (Asn) side chain that is present as a part of Asn-X-Ser/Thr consensus sequence, where X is any amino acid except proline (Pro).[4]

In animal cells, the glycan attached to the asparagine is almost inevitably N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc); in the β-configuration.[4] This β-linkage is similar to glycosidic bond between the sugar moieties in the glycan structure as described above. Instead of being attached to a sugar hydroxyl group, the anomeric carbon atom is attached to an amide nitrogen. The energy required for this linkage comes from the hydrolysis of a pyrophosphate molecule.[4]

Pathway of N-linked glycan biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of N-linked glycans occurs via 3 major steps:[4]

- Synthesis of dolichol-linked precursor oligosaccharide

- En bloc transfer of precursor oligosaccharide to protein

- Processing of the oligosaccharide

Synthesis, en bloc transfer and initial trimming of precursor oligosaccharide occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Subsequent processing and modification of the oligosaccharide chain is carried out in the Golgi apparatus.

The synthesis of glycoproteins is thus spatially separated in different cellular compartments. Therefore, the type of N-glycan synthesised, depends on its accessibility to the different enzymes present within these cellular compartments.

However, in spite of the diversity, all N-glycans are synthesised through a common pathway with a common core glycan structure.[4] The core glycan structure is essentially made up of two N-acetyl glucosamine and three mannose residues. This core glycan is then elaborated and modified further, resulting in a diverse range of N-glycan structures.[4]

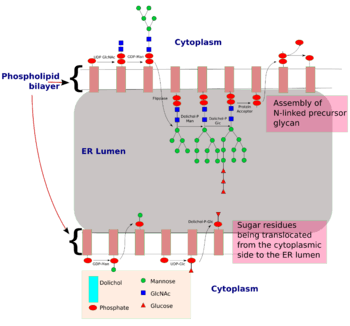

Synthesis of precursor oligosaccharide

The process of N-linked glycosylation starts with the formation of dolichol-linked GlcNAc sugar. Dolichol is a lipid molecule composed of repeating isoprene units. This molecule is found attached to the membrane of the ER. Sugar molecules are attached to the dolichol through a pyrophosphate linkage[4] (one phosphate was originally linked to dolichol, and the second phosphate came from the nucleotide sugar). The oligosaccharide chain is then extended through the addition of various sugar molecules in a step-wise manner to form a precursor oligosaccharide.

The assembly of this precursor oligosaccharide occurs in two phases: Phase I and II.[4] Phase I takes place on the cytoplasmic side of the ER and Phase II takes place on the luminal side of the ER.

The precursor molecule, ready to be transferred to a protein, consist of 2 GlcNAc, 9 mannose and 3 glucose molecules.

| | |

|---|---|

| | |

|

|

|

| |

| Phase II | |

is the Mannose residue donor(formation : Dol-P + GDP-Man ----> Dol-P-Man + GDP) and Dol-P-Gluc is the glucose residue donor (formation : Dol-P + UDP-Glc ----> Dol-P-Glc + UDP).

|

|

En bloc transfer of glycan to protein

Once the precursor oligosaccharide is formed, the completed glycan is then transferred to the nascent polypeptide in the lumen of the ER membrane. This reaction is driven by the energy released from the cleavage of the pyrophosphate bond between the dolichol-glycan molecule. There are three conditions to fulfill before a glycan is transferred to a nascent polypeptide:[4]

- Asparagine must be located in a specific consensus sequence in the primary structure (Asn-X-Ser or Asn-X-Thr or in rare instances Asn-X-Cys).[5]

- Asparagine must be located appropriately in the three dimensional structure of the protein (Sugars are polar molecules and thus need to be attached to asparagine located on surface of the protein and not buried within the protein)

- Asparagine must be found in the luminal side of the endoplasmic reticulum for N-linked glycosylation to be initiated. Target residues are either found in secretory proteins or in the regions of transmembrane protein that faces the lumen.

Oligosaccharyltransferase is the enzyme responsible for the recognition of the consensus sequence and the transfer of the precursor glycan to a polypeptide acceptor which is being translated in the endoplasmic reticulum lumen. N-linked glycosylation is therefore, is a co-translational event

Processing of glycan

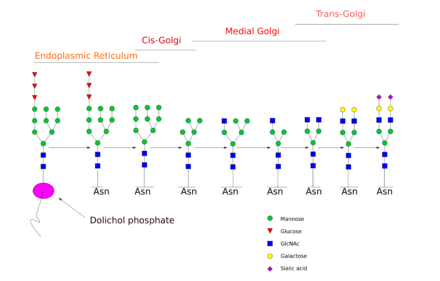

N-glycan processing is carried out in endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi body. Initial trimming of the precursor molecule occurs in the ER and the subsequent processing occurs in the Golgi.

Upon transferring the completed glycan onto the nascent polypeptide, three glucose residues are removed from the structure. Enzymes known as glycosidases remove some sugar residues. These enzymes can break glycosidic linkages by using a water molecule. These enzymes are exoglycosidases as they only work on monosaccharide residues located at the non-reducing end of the glycan.[4] This initial trimming step is thought to act as a quality control step in the ER to monitor protein folding.

Once the protein is folded correctly, the three glucose residues are removed by glucosidase I and II. The removal of the final glucose residue signals that the glycoprotein is ready for transit from the ER to the cis-Golgi.[4] However, if the protein is not folded properly, the glucose residues are not removed and thus the glycoprotein can’t leave the endoplasmic reticulum. A chaperone protein (calnexin/calreticulin) binds to the unfolded or partially folded protein to assist protein folding.

The next step involves further addition and removal of sugar residues in the Golgi. These modifications are catalyzed by glycosyltransferases and glycosidases respectively. In the cis-Golgi, a series of mannosidases remove some or all of the four mannose residues in α-1,2 linkages.[4] Whereas in the medial portion of the Golgi, glycosyltransferases add sugar residues to the core glycan structure, giving rise to the three main types of glycans: high mannose, hybid and complex glycans.

- High-mannose is, in essence, just two N-acetylglucosamines with many mannose residues, often almost as many as are seen in the precursor oligosaccharides before it is attached to the protein.

- Complex oligosaccharides are so named because they can contain almost any number of the other types of saccharides, including more than the original two N-acetylglucosamines.

- Hybrid oligosaccharides contain a mannose residues on one side of the branch, while on the other side a N-acetylglucosamine initiates a complex branch.

The order of addition of sugars to the growing glycan chains is determined by the substrate specificities of the enzymes and their access to the substrate as they move through secretory pathway. Thus, the organization of this machinery within a cell plays an important role in determining which glycans are made.

Organization of enzymes in the Golgi

Golgi enzymes play a key role in determining the synthesis of the various types of glycans. The order of action of the enzymes is reflected in their position in the Golgi stack:

| Enzymes | Location within Golgi |

|---|---|

| Mannosidase I | cis-Golgi |

| GlcNAc transferases | medial Golgi |

| Galactosyltransferase and Sialyltransferase | trans-Golgi |

Biosynthesis pathway comparison to archaea and prokaryotes

Similar N-glycan biosynthesis pathway have been found in prokaryotes and Archaea.[6] However, compared to eukaryotes, the final glycan structure in eubacteria and archaea does not seem to differ much from the initial precursor made in the endoplasmic reticulum. In eukaryotes, the original precursor oligosaccharide is extensively modified en route to the cell surface.[4]

Functions of N-glycans

N-linked glycans have intrinsic and extrinsic functions.[4]

Within the immune system the N-linked glycans on an immune cell's surface will help dictate that migration pattern of the cell, e.g. immune cells that migrate to the skin have specific glycosylations that favor homing to that site.[7] The glycosylation patterns on the various immunoglobulins including IgE, IgM, IgD, IgE, IgA, and IgG bestow them with unique effector functions by altering their affinities for Fc and other immune receptors.[7] Glycans may also be involved in "self" and "non self" discrimination, which may be relevant to the pathophysiology of various autoimmune diseases.[7]

| | |

|---|---|

| Intrinsic |

|

| Extrinsic |

|

Clinical significance

Mutations in eighteen genes involved in N-linked glycosylation result in a variety of diseases, most of which involve the nervous system.[3]

Importance of N-linked glycosylation in the production of therapeutic proteins

Many “blockbuster” therapeutic proteins in the market are antibodies, which are N-linked glycoproteins. For example, Etanercept, Infliximab and Rituximab are N-glycosylated therapeutic proteins.

The importance of N-linked glycosylation is becoming increasingly evident in the field of pharmaceuticals.[9] Although bacterial or yeast protein production systems have significant potential advantages such as high yield and low cost, problems arise when the protein of interest is a glycoprotein. Most prokaryotic expression systems such as E.coli cannot carry out post-translational modifications. On the other hand, eukaryotic expression hosts such as yeast and animal cells, have different glycosylation patterns. The proteins produced in these expression hosts are often not identical to human protein and thus, causes immunogenic reactions in patients. For example, S.cerevisiae (yeast) often produce high-mannose glycans which are immunogenic.

Non-human mammalian expression systems such as CHO or NS0 cells have the machinery required to add complex, human-type glycans. However, glycans produced in these systems can differ from glycans produced in humans, as they can be capped with both N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc) and N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac), whereas human cells only produce glycoproteins containing N-acetylneuraminic acid. Furthermore, animal cells can also produce glycoproteins containing the galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose epitope, which can induce serious allergenic reactions, including anaphylactic shock, in people who have Alpha-gal allergy.

These drawbacks have been addressed by several approaches such as eliminating the pathways that produce these glycan structures through genetic knockouts. Furthermore, other expression systems have been genetically engineered to produce therapeutic glycoproteins with human-like N-linked glycans. These include yeasts such as Pichia pastoris,[10] insect cell lines, green plants,[11] and even bacteria.

See also

References

- ↑ "Glycosylation". UniProt - Protein sequence and functional information.

- ↑ Imperiali B, O'Connor SE (Dec 1999). "Effect of N-linked glycosylation on glycopeptide and glycoprotein structure". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 3 (6): 643–9. doi:10.1016/S1367-5931(99)00021-6. PMID 10600722.

- 1 2 Patterson MC (Sep 2005). "Metabolic mimics: the disorders of N-linked glycosylation". Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 12 (3): 144–51. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2005.10.002. PMID 16584073.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Drickamer K, Taylor ME (2006). Introduction to Glycobiology (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-928278-4.

- ↑ Mellquist JL, Kasturi L, Spitalnik SL, Shakin-Eshleman SH (May 1998). "The amino acid following an asn-X-Ser/Thr sequon is an important determinant of N-linked core glycosylation efficiency". Biochemistry. 37 (19): 6833–7. doi:10.1021/bi972217k. PMID 9578569.

- ↑ Dell A, Galadari A, Sastre F, Hitchen P (2010). "Similarities and differences in the glycosylation mechanisms in prokaryotes and eukaryotes". International Journal of Microbiology. 2010: 148178. doi:10.1155/2010/148178. PMC 3068309

. PMID 21490701.

. PMID 21490701. - 1 2 3 Maverakis E, Kim K, Shimoda M, Gershwin ME, Patel F, Wilken R, Raychaudhuri S, Ruhaak LR, Lebrilla CB (Feb 2015). "Glycans in the immune system and The Altered Glycan Theory of Autoimmunity: a critical review". Journal of Autoimmunity. 57 (6): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2014.12.002. PMC 4340844

. PMID 25578468.

. PMID 25578468. - ↑ Sinclair AM, Elliott S (Aug 2005). "Glycoengineering: the effect of glycosylation on the properties of therapeutic proteins". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 94 (8): 1626–35. doi:10.1002/jps.20319. PMID 15959882.

- ↑ Dalziel, M; Crispin, M; Scanlan, CN; Zitzmann, N; Dwek, RA (Jan 2014). "Emerging principles for the therapeutic exploitation of glycosylation". Science. 343 (6166): 1235681. doi:10.1126/science.1235681.

- ↑ Hamilton SR, Bobrowicz P, Bobrowicz B, Davidson RC, Li H, Mitchell T, Nett JH, Rausch S, Stadheim TA, Wischnewski H, Wildt S, Gerngross TU (Aug 2003). "Production of complex human glycoproteins in yeast". Science. 301 (5637): 1244–6. doi:10.1126/science.1088166. PMID 12947202.

- ↑ Strasser R, Altmann F, Steinkellner H (Dec 2014). "Controlled glycosylation of plant-produced recombinant proteins". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 30: 95–100. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2014.06.008. PMID 25000187.

External links

- GlycoEP : In silico Platform for Prediction of N-, O- and C-Glycosites in Eukaryotic Protein Sequences

- Maverakis E, Kim K, Shimoda M, Gershwin ME, Patel F, Wilken R, Raychaudhuri S, Ruhaak LR, Lebrilla CB (Feb 2015). "Glycans in the immune system and The Altered Glycan Theory of Autoimmunity: a critical review". Journal of Autoimmunity. 57: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2014.12.002. PMC 4340844

. PMID 25578468.

. PMID 25578468.