National Woman's Party

| |

| Formation | June 5, 1916 |

|---|---|

| Extinction | 1997 |

| Purpose | "To secure an amendment to the United States Constitution enfranchising women" and to pass the ERA |

| Headquarters | Washington, DC |

Key people | Alice Paul, Lucy Burns |

| Website | http://www.nationalwomansparty.org/ |

Formerly called | Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage |

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's organization formed in 1916 as an outgrowth of the Congressional Union, which in turn was formed in 1913 by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns to fight for women's suffrage, ignoring all other issues. It broke from the much larger National American Woman Suffrage Association, which was nationwide, and worked mostly on state suffrage in later years. The NWP prioritized the passage of a constitutional amendment ensuring women's suffrage. The National Woman's Party, like the Congressional Union, was tightly controlled by Paul, who learned from the even more militant suffragettes in Britain who used violence to gain publicity and force passage of suffrage. The strategy was to use publicity to hold the party in power, the Democratic Party and President Woodrow Wilson, responsible for the status of woman suffrage. Starting in January 1917, NWP members known as Silent Sentinels protested outside the White House. While the British suffragettes stopped their protests when Britain entered the war in 1914, and supported the British war effort, Paul continued her campaign after the US entered the war on April 6, 1917. The protesters argued that it was hypocritical for the US to fight a war for democracy in Europe, while denying its benefits to half of the US population. Similar arguments were being made in Europe, where most of the allied nations of Europe had enfranchised some women or would soon.[1]

The NWP pickets were then widely criticized for ignoring the World War and attracting radical anti-war elements.[2] The pickets were later arrested on the charge of obstructing traffic, and in prison, some went on hunger strikes.[3] Abusive treatment of the protesters, who called themselves political prisoners, angered some Americans and created more support for the suffrage amendment. They were released and their arrests were later declared unconstitutional. In the meantime, NAWSA helped pass the 1917 referendum in New York State in favor of suffrage. In early 1918, Wilson came out in favor of the amendment, and it passed the House, but failed in the Senate despite another round of protests and arrests. After the NWP helped replace anti-suffrage senators in the 1918 elections, the amendment finally passed both houses and was sent to the states for ratification. The Nineteenth amendment was ratified by enough states by 1920, thus giving women the vote.

After ratification, the NWP turned its attention to passage of an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution. Historian Nancy Cott says that as the party moved into the 1920s:

- it remained an autocratically run, single-minded and single-issue pressure group, still reliant on getting into the newspapers as a means of publicizing its cause, very insistent on the method of "getting in touch with the key men."...NWP lobbyists went straight to legislators, governors, and presidents, not to their constituents.[4]

Today, the National Woman's Party exists as a 501c3 educational organization. It's task is now the maintenance and interpretation of the collection and archives of the historic National Woman's Party [5] The NWP operates out of the Belmont-Paul Women's Equality National Monument in Washington, DC, where objects from the collection are exhibited.

Early history

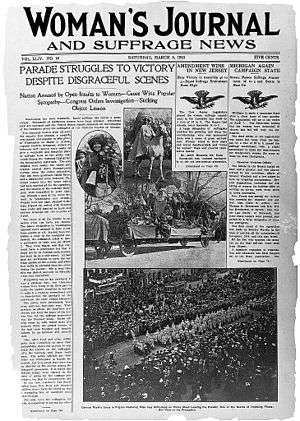

After their experience with militant suffrage work in Great Britain, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns reunited in the United States in 1910. The two women originally were appointed to the Congressional Committee of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. In March 1913, the two women organized a parade of 5,000–8,000 women (by differing estimates) in Washington, D.C. on the day before Woodrow Wilson's inauguration. Though beautifully planned as an elegant progression of symbolically dressed, accomplished, and professional women, the parade quickly devolved into riot. The D.C. police did little to help them; the women were assisted by the Massachusetts National Guard, the Pennsylvania National Guard, and boys from the Maryland Agricultural College, who created a human barrier protecting the women from the angry crowd.[6]

After this incident, which Paul used to rally public opinion to the women's cause, Paul and Burns founded the Congressional Union in April 1913, which split off from NAWSA later that year. The Congressional Union began publishing a weekly newspaper, The Suffragist, in November 1913. Paul and Burns were mostly frustrated with the National's slower approach of focusing on individual state referendums; they were pursued the congressional amendment. Alice Paul had also chafed under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt, as she had very different ideas of how to go about suffrage work, and a different attitude towards militancy.[7]

The split was confirmed by a major difference of opinion on the Shafroth-Palmer Amendment. This amendment was spearheaded by Alice Paul's replacement as chair of the National's Congressional Committee, and was a compromise of sorts meant to appease the racist South. Shafroth–Palmer was to be a constitutional amendment that would require any state with more than 8 percent signing an initiative petition to hold a state referendum on suffrage. This would have kept the law-making out of federal hands, a proposition more attractive to the South. Southern states feared a congressional women's suffrage amendment as a possible federal encroachment into their restrictive system of voting laws, meant to disenfranchise the black voter.

Paul and Burns felt that this amendment was a lethal distraction from the true and ultimately necessary goal of an all-encompassing federal amendment protecting the rights of all women—especially as the bruising rounds of state referendums were perceived at the time as almost damaging the cause. In Paul's words: "It is a little difficult to treat with seriousness an equivocating, evasive, childish substitute for the simple and dignified suffrage amendment now before Congress."[8]

Portrait of Alice Paul, 1915

Portrait of Alice Paul, 1915 Lucy Burns, Vice Chairman Congressional Union, 1913

Lucy Burns, Vice Chairman Congressional Union, 1913 Rheta Childe Dorr, first editor of The Suffragist

Rheta Childe Dorr, first editor of The Suffragist

Militant suffragists

Women associated with the party staged a suffrage parade on March 3, 1913, the day before Wilson's inauguration.[9]

During the group's first meeting, Paul clarified that the party would not be a political party and therefore would not endorse a candidate for president during elections. While non-partisan, the NWP directed most of its fire at President Woodrow Wilson and the Democrats, criticizing them as responsible for the failure to pass a constitutional amendment. The National Woman's Party continued to focus on suffrage as their main cause. It refused to support (or attack) American involvement in the World War, while the rival National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) under Carrie Chapman Catt gave full support to the war effort. As a result, anti-war radicals and Socialists were attracted to the NWP, further weakening its appeal to mainstream women.[10] Its lobbying technique focused exclusively powerful men, ignoring the grass roots where the NAWSA put its efforts.[11]

Picketing the White House

While the British suffragettes stopped their protests in 1914 and supported the British war effort, Paul began her campaign in 1917 and was widely criticized for ignoring the war and attracting radical anti-war women to picket for women's rights in front of the White House. Known as "Silent Sentinels", their action lasted from January 10, 1917 until June 1919. The picketers were tolerated at first, but when they continued to picket after the United States declared war in 1917, they were arrested by police for obstructing traffic. Many of the NWP's members, upon arrest, went on hunger strikes; some, including Paul, were force-fed by jail personnel as a consequence. Anne Henrietta Martin, the NWP's first vice chairman, was sentenced to the Occoquan Workhouse, though Wilson pardoned her in less than a week.[12] Other suffragists arrested during the picket included Helena Hill and Iris Calderhead. The resulting publicity at a time when Wilson was trying to build a reputation for himself and the nation as an international leader in human rights was designed to force Wilson to publicly call for the Congress to pass the Suffrage Amendment.[13]

Wilson favored woman suffrage at the state level, but held off support for a nationwide constitutional amendment because his party was sharply divided, with the South opposing an amendment on the grounds of state's rights. The only Southern state to grant women the vote was Arkansas. The NWP in 1917–1919 repeatedly attacked Wilson and his party for not enacting an amendment. Wilson, however, kept in close touch with the much larger and more moderate suffragists of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. He continued to hold off until he was sure the Democratic Party in the North was supportive; the 1917 referendum in New York State in favor of suffrage proved decisive for him. In January, 1918, Wilson went in person to the House and made a strong and widely published appeal to the House to pass the bill. It passed but the Senate stalled until 1919 then finally sent the amendment to the states for ratification.[14] Behn argues that:

- The National American Woman Suffrage Association, not the National Woman's Party, was decisive in Wilson's conversion to the cause of the federal amendment because its approach mirrored his own conservative vision of the appropriate method of reform: win a broad consensus, develop a legitimate rationale, and make the issue politically valuable. Additionally, I contend that Wilson did have a significant role to play in the successful congressional passage and national ratification of the 19th Amendment.[1]

Wilson did make such a call but only by working closely with the much larger NAWSA organization and after suffrage won in the key New York state referendum.[15]

Fighting for equal rights

After the ratification of the Nineteenth amendment in 1920, the NWP turned its attention to eliminating other forms of gender discrimination, principally by advocating passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, which Paul drafted in 1923. The organization regrouped and published the magazine Equal Rights. The publication was directed towards women but also intended to educate men about the benefits of women's suffrage, women's rights and other issues concerning American women.

"Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction."[16]

The NWP's agenda was sometimes opposed by working class women and by the labor unions that represented working class men who feared low-wage women workers would lower the overall pay scale and demean the role of the male breadwinner. Eleanor Roosevelt, an ally of the unions, generally opposed the NWP policies because she believed women needed protection, not equality.[17] However, the National Woman's Party found protective legislation to relegate women to a lower class, and aimed their work on the ERA and other legislation to combat this second class citizenship status. The NWP argued that protective labor legislation would continue to depress women's wages and prevent women from gaining access to all types of work and parts of society.

After 1920, the National Woman's Party authored over 600 pieces of legislation fighting for women's equality; over 300 of these were passed. In addition, the NWP continued to lobby for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment.[18] In 1997, the NWP ceased to be a lobbying organization. Instead, it turned its focus to education and to preserving its collection of first hand source documents from the women's suffrage movement. The NWP continues to function as an educational organization, maintaining and interpreting the collection left by the work of the historic National Woman's Party.

Congress passed the ERA Amendment and many states ratified it, but at the last minute in 1982 it was stopped by a coalition of conservatives led by Phyllis Schlafly and never passed. However, in 1964 the NWP did succeed, with the support of conservatives and over the opposition of liberals, blacks and labor unions, to have "sex" added to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, thus achieving some of the goals sought by the NWP.

Civil Rights Act of 1964

In 1963 Congress passed the Equal Pay Act of 1963, which prohibited wage differentials based on sex.

The prohibition on sex discrimination was added by Howard W. Smith, a powerful Virginian Democrat who chaired the House Rules Committee; he was a conservative who strongly opposed civil rights laws for blacks. But he supported such laws for women. Smith's amendment was passed by a teller vote of 168 to 133.

Historians debate Smith's motivation—was it a cynical attempt to defeat the bill by someone opposed to both civil rights for blacks and women, or did he support women's rights and was attempting to improve the bill by broadening it to include women?[19][20][21] Smith expected that Republicans, who had included equal rights for women in their party's platform since 1944, would probably vote for the amendment. Historians speculate that Smith was trying to embarrass northern Democrats who opposed civil rights for women because the clause was opposed by labor unions.[22]

Smith was not joking: he asserted that he sincerely supported the amendment and, indeed, along with Rep. Martha Griffiths,[23] he was the chief spokesperson for the amendment.[22] For twenty years Smith had sponsored the Equal Rights Amendment—with no linkage to racial issues—in the House because he believed in it. For decades he had been close to the National Woman's Party and especially Paul. She and other activists had worked with Smith since 1945 trying to find a way to include sex as a protected civil rights category. Now was the moment.[24] Griffith argued that the new law would protect black women but not white women, and that was unfair to white women. Furthermore, she argued that the laws "protecting" women from unpleasant jobs were actually designed to enable men to monopolize those jobs, and that was unfair to women who were not allowed to try out for those jobs.[25] The amendment passed with the votes of Republicans and Southern Democrats. The final law passed with the votes of Republicans and Northern Democrats.

Publications

The Suffragist newspaper was founded by the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage in 1913. It was referred to as "the only women's political newspaper in the United States" and was published to promote women's suffrage activities.[26] Its articles had political cartoons, a form of visual propaganda, by Nina E. Allender to garner support for the movement and communicate the status of the suffrage amendment.[26]

The woman who reads our paper will be informed as to happenings in Congress, not only suffrage happenings, although they come first, but all proceedings of special interest to women. Men do not realize how serious are the changes that are taking place in the conduct of Congress. Women will have to inform them. Only in the pages of The Suffragist will you find the information you need.— The Suffragist, 1914[26]

After the amendment for the women's right to vote was passed, the publication was discontinued by the National Woman's Party and succeeded in 1923 by Equal Rights.[26] Published until 1954, Equal Rights began as a weekly newsletter and evolved into a bi-monthly release aimed at keeping NWP members informed about developments related to the ERA and legislative issues. It included field reports, legislation updates and features about the activities of the NWP and featured writing from contributors including Crystal Eastman, Zona Gale, Ruth Hale and Inez Haynes Irwin.[27] Josephine Casey appeared on the cover of the publication in April 1931 as a result of her recurring column about the labour conditions of female textile workers in Georgia.[28]

Notable members

- Nina E. Allender

- Caroline Lexow Babcock

- Abby Scott Baker

- Alva Belmont

- Lucy Burns

- Marion Cothren

- Rheta Childe Dorr

- Crystal Eastman

- Sara Bard Field

- Alison Turnbull Hopkins

- Inez Haynes Irwin

- Edna Buckman Kearns

- Anne Martin

- Inez Milholland

- Alice Paul

- Doris Stevens

- Mabel Vernon

- Amelia Earhart

See also

- Silent Sentinels

- Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913

- Suffrage Hikes

- History of Feminism

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- Timeline of women's rights (other than voting)

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Women's suffrage organizations

- Iron Jawed Angels

Further reading

- Adams, Katherine H.; Keene, Michael L. (2008). Alice Paul and the American Suffrage Campaign. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07471-4. The standard scholarly biography; online review

- Behn, Beth (2012). Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment (Ph.D. thesis). University of Massachusetts - Amherst. Retrieved 2015-01-25.

- Butler, Amy E. Two Paths to Equality: Alice Paul and Ethel M. Smith in the Era Debate, 1921–1929 (2002)

- Cooney, Robert P. J. Winning the Vote: The Triumph of the American Woman Suffrage Movement. Santa Cruz, CA: American Graphic Press, 2005.

- Cott, Nancy F. (1987). The Grounding of Modern Feminism. Yale University Press. pp. 51–82. ISBN 0-300-03892-5.

- Dodd, Lynda G. (2008). "Parades, pickets, and prison: Alice Paul and the virtues of unruly constitutional citizenship". Journal of Law & Politics. 24 (4): 339–443. SSRN 2226351

.

. - Lunardini, Christine A. (2000). From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910–1928. ISBN 978-0595000555. The standard scholarly history.

- Walton, Mary (2010). A Woman's Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-61175-7.

References

- 1 2 Behn (2012).

- ↑ Cott (1987), pp. 51–82.

- ↑ name="nationalwomansparty.org" "Learn:National Woman's Party".

- ↑ Cott (1987), p. 80.

- ↑ "About the NWP".

- ↑ Baltimore Sun, March 4, 1913

- ↑ Flexner, Eleanor (1959). Century of Struggle: The Woman's Rights Movement in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 259. ISBN 0-674-10654-7.

- ↑ Adams & Keene (2008), p. 103.

- ↑ Eleanor Flexner, Century of Struggle, enlarged edition (1959; Harvard University Press, 1996), pp. 255–257.

- ↑ Cott (1987), pp. 59–61.

- ↑ Cott (1987), p. 60.

- ↑ "Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party". Doris Stevens, Jailed for Freedom (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1920), 364. The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ↑ Doris Stevens, Jailed for Freedom, edited by Ronald McDonald (1920; NewSage Press, 1995), pp. 59–136.

- ↑ Lunardini, Christine A.; Knock, Thomas J. (1980). "Woodrow Wilson and woman suffrage: A new look". Political Science Quarterly. 95 (4): 655–671. doi:10.2307/2150609. JSTOR 2150609.

- ↑ John Milton Cooper, Jr., Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2009) pp 412–13

- ↑ Carol, Rebecca; Myers, Kristina; Lindman, Janet. "The Equal Rights Amendment". Alice Paul: Feminist, Suffragist and Political Strategist. Alice Paul Institute. Retrieved 10 Feb 2016.

- ↑ Paula F. Pfeffer, "Eleanor Roosevelt and the National and World Woman's Parties," Historian, Fall 1996, Vol. 59, Issue 1

- ↑ Leila J. Rupp and Verta Taylor, Survival in the Doldrums (Oxford University Press, 1987), pp. 24–44.

- ↑ Freeman, Jo (March 1991). "How 'Sex' Got Into Title VII: Persistent Opportunism as a Maker of Public Policy". Law and Inequality. 9 (2): 163–184.

- ↑ Rosalind Rosenberg, Divided Lives: American Women in the Twentieth Century (2008) p. 187–88

- ↑ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. pp. 245–246, 249. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- 1 2 Gold, Michael Evan (1981). "A Tale of Two Amendments: The Reasons Congress Added Sex to Title VII and Their Implication for the Issue of Comparable Worth". Faculty Publications – Collective Bargaining, Labor Law, and Labor History. Cornell University Press.

- ↑ Lynne Olson, Freedom's daughters: the unsung heroines of the civil rights movement (2001) p 360

- ↑ Rosalind Rosenberg, Divided Lives: American Women in the Twentieth Century (2008) p. 187 notes that Smith had been working for years with two Virginia feminists on the issue.

- ↑ Cynthia Harrison, On Account of Sex: The Politics of Women's Issues, 1945–1968 (1989) p. 179

- 1 2 3 4 "Suffragist Newspapers". National Woman's Party. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Equal Rights Newspapers". National Woman's Party. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ↑ Storrs, Landon R.Y. (2000). Civilizing Capitalism: The National Consumers' League, Women's Activism, and Labor Standards in the New Deal Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-6099-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Woman's Party. |

- National Woman's Party

- Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party

- Detailed Chronology of National Woman's Party