Noise

Noise is unwanted sound judged to be unpleasant, loud or disruptive to hearing. From a physics standpoint, noise is indistinguishable from sound, as both are vibrations through a medium, such as air or water. The difference arises when the brain receives and perceives a sound.[1][2]

In experimental sciences, noise can refer to any random fluctuations of data that hinders perception of an expected signal.[3][4]

Acoustic noise is any sound in the acoustic domain, either deliberate (e.g., music or speech) or unintended. In contrast, noise in electronics may not be audible to the human ear and may require instruments for detection.[5]

In audio engineering, noise can refer to the unwanted residual electronic noise signal that gives rise to acoustic noise heard as a hiss. This signal noise is commonly measured using A-weighting[6] or ITU-R 468 weighting.[7]

Measurement

Sound is measured based on the amplitude and frequency of a sound wave. Noise is most commonly discussed in terms of decibels (dB), the measure of loudness, or intensity of a sound; this measurement describes the amplitude of a sound wave. On the other hand, pitch describes the frequency of a sound and is measured in hertz (Hz).[8]

Recording and reproduction

In audio, recording, and broadcast systems, audio noise refers to the residual low-level sound (four major types: hiss, rumble, crackle, and hum) that is heard in quiet periods of program. This variation from the expected pure sound or silence can be caused by the audio recording equipment, the instrument, or ambient noise in the recording room.[9]

In audio engineering it can refer either to the acoustic noise from loudspeakers or to the unwanted residual electronic noise signal that gives rise to acoustic noise heard as 'hiss'. This signal noise is commonly measured using A-weighting or ITU-R 468 weighting

Noise is often generated deliberately and used as a test signal for audio recording and reproduction equipment.

White noise

|

White Noise

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

White noise is energy randomly spread across a wide frequency band containing all notes from high to low. It is called "white" noise as it is analagous to "white" light which contains all the colors of the visible spectrum.[10]

Environmental noise

Environmental noise is the accumulation of all noise present in a specified environment. The principal sources of environmental noise are surface motor vehicles, aircraft, trains and industrial sources.[11] These noise sources expose millions of people to noise pollution that creates not only annoyance, but also significant health consequences such as elevated incidence of hearing loss and cardiovascular disease.[12] There are a variety of mitigation strategies and controls available to reduce sound levels including source intensity reduction, land use planning strategies, noise barriers and sound baffles, time of day use regimens, vehicle operational controls and architectural acoustics design measures.

Regulation of noise

Certain geographic areas or specific occupations may be at a higher risk of being exposed to constantly high levels of noise; in order to prevent negative health outcomes, regulations may be set. Noise regulation includes statutes or guidelines relating to sound transmission established by national, state or provincial and municipal levels of government. Environmental noise is governed by laws and standards which set maximum recommended levels of noise for specific land uses, such as residential areas, areas of outstanding natural beauty, or schools. These standards usually specify measurement using a weighting filter, most often A-weighting.[13][14]

United States

In 1972, the Noise Control Act was passed to promote a healthy living environment for all Americans, where noise does not pose a threat to human health. This policy's main objectives were: (1) establish coordination of research in the area of noise control, (2) establish federal standards on noise emission for commercial products, and (3) promote public awareness about noise emission and reduction.[15][16]

The Quiet Communities Act of 1978 promotes noise control programs at the state and local level and developed a research program on noise control.[17] Both laws authorized the Environmental Protection Agency to study the effects of noise and evaluate regulations regarding noise control.[18]

Noise in the workplace

In the US, the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) provides recommendation on noise exposure in the workplace.[19][20] In 1972 (revised in 1998), NIOSH published a document outlining recommended standards relating to the occupational exposure to noise, with the purpose of reducing the risk of developing permanent hearing loss related to exposure at work.[21] This publication set the recommended exposure limit (REL) of noise in an occupation setting to 85 dBA for 8 hours. However, in 1973 the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) maintained the requirement of an 8-hour average of 90 dBA. The following year, OSHA required employers to provide a hearing conservation program to workers exposed to 85 dBA average 8-hour workdays.[22]

Europe

The European Environment Agency regulates noise control and surveillance within the European Union.[23] The Environmental Noise Directive was set to determine levels of noise exposure, increase public access to information regarding environmental noise, and reduce environmental noise.[24][25] Additionally, in the European Union, underwater noise is a pollutant according to the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD).[26] The MSFD requires EU Member States to achieve or maintain Good Environmental Status, meaning that the "introduction of energy, including underwater noise, is at levels that do not adversely affect the marine environment".[26]

Health effects from noise

Exposure to noise is associated with several negative health outcomes. Depending on duration and level of exposure, noise may cause or increase the likelihood of hearing loss, high blood pressure, ischemic heart disease, sleep disturbances, injuries, and even decreased school performance.[27]

Noise exposure has increasingly been identified as a public health issue, especially in an occupational setting, as demonstrated with the creation of NIOSH's Noise and Hearing Loss Prevention program.[28] Noise has also proven to be an occupational hazard, as it is the most common work-related pollutant.[29] Noise-induced hearing loss, when associate with exposures from the workplace is also called occupational hearing loss.

Prevention

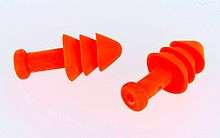

While noise-induced hearing loss is permanent, it is also very preventable.[30] Particularly in the workplace, regulations may exist depicting maximum allowed levels of noise. This can be especially important for professionals working in settings with consistent exposure to loud sounds, such as musicians, music teachers and sound engineers.[31] Examples of measures taken to prevent noise-induced hearing loss in the workplace include engineering noise control, the Buy-Quiet initiative, creation of the Safe-in-Sound Award, and noise surveillance.[32][33][34]

Literary views

Roland Barthes distinguishes between physiological noise, which is merely heard, and psychological noise, which is actively listened to. Physiological noise is felt subconsciously as the vibrations of the noise (sound) waves physically interact with the body while psychological noise is perceived as our conscious awareness shifts its attention to that noise.[35]

Luigi Russolo, one of the first composers of noise music,[36] wrote the essay The Art of Noises. He argues that any kind of noise could be used as music, as audiences become more familiar with noises caused by technological advancements; noise has become so prominent that pure sound no longer exists.[37]

Henry Cowell claims that technological advancements have reduced unwanted noises from machines, but have not managed so far to completely eliminate them.[38]

See also

References

- ↑ Elert, Glenn. "The Nature of Sound – The Physics Hypertextbook". physics.info. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ "The Propagation of sound". pages.jh.edu. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ "Definition of NOISE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ "noise: definition of noise in Oxford dictionary (American English) (US)". www.oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ "What's The Difference Between Acoustical And Electrical Noise In Components?". electronicdesign.com. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ Richard L. St. Pierre, Jr. and Daniel J. Maguire (July 2004), The Impact of A-weighting Sound Pressure Level Measurements during the Evaluation of Noise Exposure (PDF), retrieved 2011-09-13

- ↑ "RECOMMENDATION ITU-R BS.468-4 – Measurement of audio-frequency noise voltage" (PDF). www.itu.int. International Telecommunication Union. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ↑ "Measuring sound". Sciencelearn Hub. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ "Audio Noise-Hiss,Hum,Rumble & Crackle". AudioShapers. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- ↑ Elliot, Barry J. (2002). Designing a Structured Cabling System to ISO 11801 2nd Edition. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-8247-4130-3.

- ↑ Stansfeld, Stephen A.; Matheson, Mark P. (2003-12-01). "Noise pollution: non-auditory effects on health". British Medical Bulletin. 68 (1): 243–257. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldg033. ISSN 0007-1420. PMID 14757721.

- ↑ "EHP – Environmental Noise Pollution in the United States: Developing an Effective Public Health Response". ehp.niehs.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ Bhatia, Rajiv (May 20, 2014). "Noise Pollution: Managing the Challenge of Urban Sounds". Earth Journalism Network. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Noise Ordinance: Noise Regulations from U.S. Cities". www.kineticsnoise.com. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- ↑ EPA,OA,OP,ORPM,RMD, US. "Summary of the Noise Control Act". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ Noise Control Act of 1972, P.L. 92-574, 86 Stat. 1234, 42 U.S.C. § 4901 – 42 U.S.C. § 4918.

- ↑ "Text of S. 3083 (95th): Quiet Communities Act (Passed Congress/Enrolled Bill version) – GovTrack.us". GovTrack.us. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ EPA,OAR,OAA,IO, US. "Title IV – Noise Pollution". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ "CDC – Facts and Statistics: Noise – NIOSH Workplace Safety & Health". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ "CDC – NIOSH Science Blog – Understanding Noise Exposure Limits: Occupational vs. General Environmental Noise". blogs.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ "CDC – NIOSH Publications and Products – Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Exposure to Noise (73-11001)". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ "OSHA Technical Manual (OTM) | Section III: Chapter 5 – Noise". www.osha.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ "Noise: Policy Context". European Environmental Agency. June 3, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Directive – Noise – Environment – European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ "Standard Summary Project Fiche: Implementation Capacity for Environmental Noise Directive" (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- 1 2 "Our Oceans, Seas and Coasts". europa.eu.

- ↑ Passchier-Vermeer, W; Passchier, W F (2000-03-01). "Noise exposure and public health.". Environmental Health Perspectives. 108 (Suppl 1): 123–131. doi:10.2307/3454637. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1637786

. PMID 10698728.

. PMID 10698728. - ↑ "CDC – Noise and Hearing Loss Prevention – NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topi". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ Masterson, Elizabeth (2016-04-27). "Measuring the Impact of Hearing Loss on Quality of Life". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ "Noise-induced Hearing Loss". National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). National Institute of Health. March 2014. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ Kardous, Chuck; Morata, Thais; Themann, Christa; Spears, Patricia; Afanuh, Sue (2015-07-07). "Turn it Down: Reducing the Risk of Hearing Disorders Among Musicians". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ Murphy, William; Tak, SangWoo (2009-11-24). "Workplace Hearing Loss". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ "Buy Quiet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ Hudson, Heidi; Hayden, Chuck (2011-11-04). "Buy Quiet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ Barthes, Roland (1985). The Responsibility of Forms: Critical Essays on Music, Art and Representation. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 9780809080755.

- ↑ Chilvers, Ian; Glaves-Smith, John, eds. (2009). A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 619–620. ISBN 978-0-19-923965-8.

- ↑ Russolo, Luigi (2004). "The art of noises: futurist manifesto". In Cox, Christoph; Warner, Daniel, eds. Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. New York: Continuum. pp. 10ff. ISBN 978-0-8264-1615-5.

- ↑ Cowell, Henry (2004). "The joys of noise". In Cox, Christoph; Warner, Daniel, eds. Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. New York: Continuum. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8264-1615-5.

Further reading

- Kosko, Bart (2006). Noise. Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-03495-9.

- Schwartz, Hillel (2011). Making Noise: From Babel to the Big Bang & Beyond. New York: Zone Books. ISBN 978-1-935408-12-3.

External links

| Look up noise in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sound |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Noise. |

- Guidelines for Community Noise, World Health Organization, 1999

- Audio Measuring Articles – Electronics

- Mohr on Receiver Noise: Characterization, Insights & Surprises

- Noise voltage – Calculation and Measuring of Thermal Noise

- Noise at work European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA)

- Article "Noise Control Techniques"

- Mountain & Plains ERC: A NIOSH Education and Research Center for Occupational & Environmental Health & Safety

- US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, – Noise