Noise in music

In music, noise is variously described as unpitched, indeterminate, uncontrolled, loud, unmusical, or unwanted sound. Noise is an important component of the sound of the human voice and all musical instruments, particularly in unpitched percussion instruments and electric guitars (using distortion). Electronic instruments create various colours of noise. Traditional uses of noise are unrestricted, using all the frequencies associated with pitch and timbre, such as the white noise component of a drum roll on a snare drum, or the transients present in the prefix of the sounds of some organ pipes.

The influence of modernism in the early 20th century lead composers such as Edgar Varese to explore the use of noise-based sonorities in an orchestral setting. In the same period the Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo created a "noise orchestra" using instruments he called intonarumori. Later in the 20th century the term noise music came to refer to works consisting primarily of noise-based sound.

In more general usage, noise is any unwanted sound or signal. In this sense, even sounds that would be perceived as musically ordinary in another context become noise if they interfere with the reception of a message desired by the receiver.[1] Prevention and reduction of unwanted sound, from tape hiss to squeaking bass drum pedals, is important in many musical pursuits, but noise is also used creatively in many ways, and in some way in nearly all genres.

Definition of noise

In conventional musical practices sounds that are considered unmusical tend to be treated as noise.[2] Oscillations and Waves defines noise as irregular vibrations of an object, in contrast to the periodical, patterned structure of music.[3] More broadly, electrical engineering professor Bart Kosko in the introductory chapter of his book Noise defines noise as a "signal we don't like."[4] Paul Hegarty, a lecturer and noise musician, likewise assigns a subjective value to noise, writing that "noise is a judgment, a social one, based on unacceptability, the breaking of norms and a fear of violence."[5] Composer and music educator R. Murray Schafer divided noise into four categories: Unwanted noise, unmusical sound, any loud system, and a disturbance in any signaling system.[6]

In regard to what is noise as opposed to music, Robert Fink in The Origin of Music: A Theory of the Universal Development of Music claims that while cultural theories view the difference between noise and music as purely the result of social forces, habit, and custom, "everywhere in history we see man making some selections of some sounds as noise, certain other sounds as music, and in the overall development of all cultures, this distinction is made around the same sounds."[7] However, musicologist Jean-Jacques Nattiez considers the difference between noise and music nebulous, explaining that "The border between music and noise is always culturally defined—which implies that, even within a single society, this border does not always pass through the same place; in short, there is rarely a consensus ... By all accounts there is no single and intercultural universal concept defining what music might be."[8]

Noise as a feature of music

Musical tones produced by the human voice and all acoustical musical instruments incorporate noises in varying degrees. Most consonants in human speech (e.g., the sounds of f, v, s, z, both voiced and unvoiced th, Scottish and German ch) are characterised by distinctive noises, and even vowels are not entirely noise free. Wind instruments include the whizzing or hissing sounds of air breaking against the edges of the mouthpiece, while bowed instruments produce audible rubbing noises that contribute, when the instrument is poor or the player unskilful, to what is perceived as a poor tone. When they are not excessive, listeners "make themselves deaf" to these noises by ignoring them.[9]

Unpitched percussion

Many unpitched percussion instruments, such as the snare drum or maracas, make use of the presence of random sounds or noise to produce a sound without any perceived pitch.[10][11] See timbre. Unpitched percussion is typically used to maintain a rhythm or to provide accents, and its sounds are unrelated to the melody and harmony of the music. Within the orchestra unpitched percussion is termed auxiliary percussion, and this subsection of the percussion section includes all unpitched instruments of the orchestra no matter how they are played, for example the pea whistle and siren.

Traditional music

Antiquity

Although percussion instruments were generally rather unimportant in ancient Greek music, two exceptions were in dance music and ritual music of orgiastic cults. The former required instruments providing a sharply defined rhythm, particularly krotala (clappers with a dry, nonresonant sound) and kymbala (similar to finger-cymbals). The cult rituals required more exciting noises, such as those produced by drums, cymbals, jingles, and the rhombos (bull-roarer), which produced a demonic roaring noise particularly important to the ceremonies of the priests of Cybele.[12] Athenaeus (The Deipnosophists xiv.38) quotes a passage from a now-lost play, Semele, by Diogenes the Tragedian, describing an all-percussion accompaniment to some of these rites:

- And now I hear the turban-wearing women,

- Votaries of th' Asiatic Cybele,

- The wealthy Phrygians' daughters, loudly sounding

- With drums, and rhombs, and brazen-clashing cymbals,

- Their hands in concert striking on each other,

- Pour forth a wise and healing hymn to the gods.[13]

An altogether darker picture of the function of this noise music is painted by Livy in Ab urbe condita xxxix.8–10, written in the late first century BC. He describes "a Greek of mean condition ... a low operator in sacrifices, and a soothsayer ... a teacher of secret mysteries" who imported to Etruria and then to Rome a Dionysian cult which attracted a large following. All manner of debaucheries were practised by this cult, including rape and

secret murders ... [where] the bodies could not even be found for burial. Many of their audacious deeds were brought about by treachery, but most of them by force, and this force was concealed by loud shouting, and the noise of drums and cymbals, so that none of the cries uttered by the persons suffering violation or murder could be heard abroad.[14]

Polynesia

A Tahitian traditional dance genre dating back to before the first contact with European explorers is ʻōteʻa, danced by a group of men accompanied solely by a drum ensemble. The drums consist of a slit-log drum called tō‘ere (which provides the main rhythmic pattern), a single-headed upright drum called fa‘atete, a single-headed hand drum called pahu tupa‘i rima, and a double-headed bass drum called tariparau.[15]

Asia

In Shaanxi in the north of China, drum ensembles accompany yangge dance, and in the Tianjin area there are ritual percussion ensembles such as the Fagu hui Dharma-drumming associations, often consisting of dozens of musicians.[16] In Korea, a style of folk music called Nongak (farmers' music) or pungmul has been performed for many hundred years, both by local players and by professional touring bands at concerts and festivals. It is loud music meant for outdoor performance, played on percussion instruments such as the drums called janggu and puk, and the gongs ching and kkwaenggwari. It originated in simple work rhythms to assist repetitive tasks carried out by field workers.[17]

South Asian music places a special emphasis on drumming, which is freed from the primary time-keeping function of drumming found in other part of the world.[18] In North India, secular processional bands play an important role in civic festival parades and the bārāt processions leading a groom's wedding party to the bride's home or the hall where a wedding is held. These bands vary in makeup, depending on the means of the families employing them and according to changing fashions over time, but the core instrumentation is a small group of percussionists, usually playing a frame drum (ḍaphalā), a gong, and a pair of kettledrums (nagāṛā). Better-off families will add shawms (shehnai) to the percussion, while the most affluent who also prefer a more modern or fashionable image may replace the traditional ensemble with a brass band.[19] The Karnatic music of southern India includes a tradition of instrumental temple music in the state of Kerala, called kṣētram vādyam. It includes three main genres, all focussed on rhythm and featuring unpitched percussion. Thayambaka in particular is a virtuoso genre for unpitched percussion only: a solo double-headed cylindrical drum called chenda, played with a pair of sticks, and accompanied by other chenda and elathalam (pairs of cymbals). The other two genres, panchavadyam and pandi melam add wind instruments to the ensemble, but only as accompaniment to the primary drums and cymbals. A panchavadyam piece typically lasts about an hour, while a pandi melam performance may be as long as four hours.[20]

Turkey

The Turkish janissaries military corps had included since the 14th century bands called mehter or mehterân which, like many other earlier military bands in Asia featured a high proportion of drums, cymbals, and gongs, along with trumpets and shawms. The high level of noise was pertinent to their function of playing on the battlefield to inspire the soldiers.[21] The focus in these bands was on percussion. A full mehterân could include several bass drums, multiple pairs of cymbals, small kettledrums, triangles, tambourines, and one or more Turkish crescents.[22]

Europe

Through Turkish ambassadorial visits and other contacts, Europeans gained a fascination with the "barbarous", noisy sound of these bands, and a number of European courts established "Turkish" military ensembles in the late-17th and early 18th centuries. The music played by these ensembles, however, were not authentically Turkish music, but rather compositions in the prevalent European manner.[23] The general enthusiasm quickly spread to opera and concert orchestras, where the combination of bass drum, cymbals, tambourines, and triangles were collectively referred to as "Turkish music". The best-known examples include Haydn's Symphony No. 100, which acquired its nickname, "The Military", from its use of these instruments, and three of Beethoven's works: the "alla marcia" section from the finale of his Symphony No. 9 (an early sketch reads: "end of the Symphony with Turkish music"), his "Wellington's Victory"—or Battle Symphony—with picturesque sound effects (the bass drums are designated as "cannons", side drums represent opposing troops of soldiers, and ratchets the sound of rifle fire), and the "Turkish March" (with the expected bass drum, cymbals, and triangle) and the "Chorus of Dervishes" from his incidental music to The Ruins of Athens, where he calls for the use of every available noisy instrument: castanets, cymbals, and so forth.[24][25][26] By the end of the 18th century, the batterie turque had become so fashionable that keyboard instruments were fitted with devices to simulate the bass drum (a mallet with a padded head hitting the back of the sounding board), cymbals (strips of brass striking the lower strings), and the triangle and bells (small metal objects struck by rods). Even when percussion instruments were not actually employed, certain alla turca "tricks" were used to imitate these percussive effects. Examples include the "Rondo alla turca" from Mozart's Piano Sonata, K. 331, and part of the finale of his Violin Concerto, K. 219.[27]

Harpsichord, piano, and organ

At about the same time that "Turkish music" was coming into vogue in Europe, a fashion for programmatic keyboard music opened the way for the introduction of another kind of noise in the form of the keyboard cluster, played with the fist, flat of the hand, forearm, or even an auxiliary object placed on the keyboard. On the harpsichord and piano, this device was found mainly in "battle" pieces, where it was used to represent cannon fire. The earliest instance was by Jean-François Dandrieu, in Les Caractères de la guerre (1724), and for the next hundred years it remained predominantly a French feature, with examples by Michel Corrette (La Victoire d'un combat naval, remportée par une frégate contre plusieurs corsaires réunis, 1780), Claude-Bénigne Balbastre (March des Marseillois, 1793), Pierre Antoine César (La Battaille de Gemmap, ou la prise de Mons, ca. 1794), and Jacques-Marie Beauvarlet-Charpentier (Battaille d'Austerlitz, 1805). In 1800, Bernard Viguerie introduced the sound to chamber music, in the keyboard part of a piano trio titled La Bataille de Maringo, pièce militaire et historique.[28] The last time this pianistic "cannon" effect was used before the 20th century was in 1861, in a depiction of the then-recent The Battle of Manassas in a piece by the black American piano virtuoso "Blind Tom" Bethune, a piece that also feature vocalised sound-effect noises.[29]

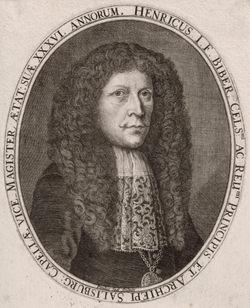

Clusters were also used on the organ, where they proved more versatile (or their composers more imaginative). Their most frequent use on this instrument was to evoke the sound of thunder, but also to portray sounds of battle, storms at sea, earthquakes, and Biblical scenes such as the fall of the walls of Jericho and visions of the apocalypse. The noisy sound nevertheless remained a special sound effect, and was not integrated into the general texture of the music. The earliest examples of "organ thunder" are from descriptions of improvisations by Abbé Vogler in the last quarter of the 18th century. His example was soon imitated by Justin Heinrich Knecht (Die durch ein Donerwetter [sic] unterbrochne Hirtenwonne, 1794), Michel Corrette (who employed a length of wood on the pedal board and his elbow on the lowest notes of the keyboard during some improvisations), and also in composed works by Guillaume Lasceux (Te Deum: "Judex crederis", 1786), Sigismond Neukomm (A Concert on a Lake, Interrupted by a Thunderstorm), Louis James Alfred Lefébure-Wély (Scène pastorale, 1867), Jacques Vogt (Fantaisie pastorale et orage dans les Alpes, ca. 1830), and Jules Blanc (La procession, 1859).[30] The most notable 19th-composer to use such organ clusters was Giuseppe Verdi. The storm music which opens his opera Otello (1887) includes an organ cluster (C, C♯, D) that is also the longest notated duration of any scored musical texture.[31]

Bowed strings

Percussive effects in imitation of drumming had been introduced to bowed-string instruments by early in the 17th century. The earliest known use of col legno (tapping on the strings with the back of the bow) is found in Tobias Hume's First Part of Ayres for unaccompanied viola da gamba (1605), in a piece titled Harke, Harke.[32] Carlo Farina, an Italian violinist active in Germany, also used col legno to mimic the sound of a drum in his Capriccio stravagante for four stringed instruments (1627), where he also used devices such as glissando, tremolo, pizzicato, and sul ponticello to imitate the noises of barnyard animals (cat, dog, chicken).[33] Later in the century, Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber, in certain movements of Battalia (1673), added to these effects the device of placing a sheet of paper under the A string of the double bass, in order to imitate the dry rattle of a snare drum, and in "Die liederliche Gesellschaft von allerley Humor" from the same programmatic battle piece, superimposed eight different melodies in different keys, producing in places dense orchestral clusters. He also uses the percussive snap of fortissimo pizzicato to represent gunshots.[34]

An important aspect of all of these examples of noise in European keyboard and string music before the 19th century is that they are used as sound effects in programme music. Sounds that would likely cause offense in other musical contexts are made acceptable by their illustrative function. Over time, their evocative effect was weakened as at the same time they became incorporated more generally into abstract musical contexts.[35]

Orchestras

Orchestras continued to use noise in the form of a percussion section, which expanded though the 19th century: Berlioz was perhaps the first composer to thoroughly investigate the effects of different mallets on the tone color of timpani.[36] However, before the 20th century, percussion instruments played a very small role in orchestral music and mostly served for punctuation, to highlight passages, or for novelty. But by the 1940s, some composers were influenced by non-Western music as well as jazz and popular music, and began incorporating marimbas, vibraphones, xylophones, bells, gongs, cymbals, and drums.[36]

Vocal music

In vocal music, noisy nonsense syllables were used to imitate battle drums and cannon fire long before Clément Janequin made these devices famous in his programmatic chanson La bataille (The Battle) in 1528.[37] Unpitched or semi-pitched performance was introduced to formal composition in 1897 by Engelbert Humperdinck, in the first version of his melodrama, Königskinder. This style of performance is believed to have been used previously by singers of lieder and popular songs. The technique is best known, however, from somewhat later compositions by Arnold Schoenberg, who introduced it for solo voices in his Gurrelieder (1900–11), Pierrot Lunaire (1913), and the opera Moses und Aron (1930–32), and for chorus in Die Glückliche Hand (1910–13). Later composers who have made prominent use of the device include Pierre Boulez, Luciano Berio, Benjamin Britten (in Death in Venice, 1973), Mauricio Kagel, and Wolfgang Rihm (in his opera Jakob Lenz, 1977–78, amongst other works).[38] A well-known example of this style of performance in popular music was Rex Harrison's portrayal of Professor Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady.[39] Another form of unpitched vocal music is the speaking chorus, prominently represented by Ernst Toch's 1930 Geographical Fugue, an example of the Gebrauchsmusik fashionable in Germany at that time.[40]

Machine music

In the 1920s a fashion emerged for composing what was called "machine music"—the depiction in music of the sounds of factories, locomotives, steamships, dynamos, and other aspects of recent technology that both reflected modern, urban life and appealed to the then-prevalent spirit of objectivity, detachment, and directness. Representative works in this style, which features motoric and insistent rhythms, a high level of dissonance, and often large percussion batteries, are George Antheil's Ballet mécanique (1923–25), Arthur Honegger's Pacific 231 (1923), Sergei Prokofiev's ballet Le pas d'acier (The Steel Leap, 1925–26), Alexander Mosolov's Iron Foundry (an orchestral episode from his ballet Steel, 1926–27), and Carlos Chávez's ballet Caballos de vapor, also titled HP (Horsepower, 1926–32). This trend reached its apex in the music of Edgard Varèse, who composed Ionisation in 1931, a "study in pure sonority and rhythm" for an ensemble of thirty-five unpitched percussion instruments.[41]

Percussion ensembles

Following Varèse's example, a number of other important works for percussion ensemble were composed in the 1930s and 40s: Henry Cowell's Ostinato Pianissimo (1934) combines Latin American, European, and Asian percussion instruments; John Cage's First Construction (in Metal) (1939) employs differently pitched thunder sheets, brake drums, gongs, and a water gong; Carlos Chávez's Toccata for percussion instruments (1942) requires six performers to play a large number of European and Latin-American drums and other unpitched percussion together with a few tuned instruments such as xylophone, tubular chimes, and glockenspiel; Lou Harrison, in works such as the Canticles nos. 1 and 3 (1940 and 1942), Song of Queztalcoatl (1941), Suite for Percussion (1942), and—in collaboration with John Cage—Double Music (1941) explored the use of "found" instruments, such as brake drums, flowerpots, and metal pipes. In all of these works, elements such as timbre, texture, and rhythm take precedence over the usual Western concepts of harmony and melody.[42]

Experimental and avant-garde music

Use of noise was central to the development of experimental music and avant-garde music in the mid 20th century. Noise was used in important, new ways.

Edgard Varèse challenged traditional conceptions of musical and non-musical sound and instead incorporated noise based sonorities into his compositional work, what he referred to as "organised sound."[43] Varèse stated that "to stubbornly conditioned ears, anything new in music has always been called noise", and he posed the question, "what is music but organized noises?".[44]

In the years immediately following the First World War, Henry Cowell composed a number of piano pieces featuring tone clusters and direct manipulation of the piano's strings. One of these, titled The Banshee (1925), features sliding and shrieking sounds suggesting the terrifying cry of the banshee from Irish folklore.[45]

In 1938 for a dance composition titled Bacchanale, John Cage invented the prepared piano, producing both transformed pitches and colorful unpitched sounds from the piano.[46] Many variations, such as prepared guitar, have followed.[47] In 1952, Cage wrote 4′33″, in which there is no deliberate sound at all, but only whatever background noise occurs during the performance.

Karlheinz Stockhausen employed noise in vocal compositions, such as Momente (1962–64/69), in which the four choirs clap their hands, talk, and shuffle their feet, in order to mediate between instrumental and vocal sounds as well as to incorporate sounds normally made by audiences into those produced by the performers.[48]

Robert Ashley used audio feedback in his avant-garde piece The Wolfman (1964) by setting up a howl between the microphone and loudspeaker and then singing into the microphone in way that modulated the feedback with his voice.[49]

Electronic music

.jpg)

Noise is used as basic tonal material in electronic music.

When pure-frequency sine tones were first synthesised into complex timbres, starting in 1953, combinations using inharmonic relationships (noises) were used far more often than harmonic ones (tones).[50] Tones were seen as analogous to vowels, and noises to consonants in human speech, and because traditional music had emphasised tones almost exclusively, composers of electronic music saw scope for exploration along the continuum stretching from single, pure (sine) tones to white noise (the densest superimposition of all audible frequencies)—that is, from entirely periodic to entirely aperiodic sound phenomena. In a process opposite to the building up of sine tones into complexes, white noise could be filtered to produce sounds with different bandwidths, called "coloured noises", such as the speech sounds represented in English by sh, f, s, or ch. An early example of an electronic composition composed entirely by filtering white noise in this way is Henri Pousseur's Scambi (Exchanges), realised at the Studio di Fonologia in Milan in 1957.[51]

In the 1980s, electronic white noise machines became commercially available.[52] These are used alone to provide a pleasant background noise and to mask unpleasant noise, a similar role to conventional background music.[53] This usage can have health applications in the case of individuals struggling with over-stimulation or sensory processing disorder.[53][54] Also, white noise is sometimes used to mask sudden noise in facilities with research animals.[55]

Rock music

While the electric guitar was originally designed to be simply amplified in order to reproduce its sound at a higher volume,[56] guitarists quickly discovered the creative possibilities of using the amplifier to modify the sound, particularly by extreme settings of tone and volume controls.[57]

Distortion was at first produced by simply overloading the amplifier to induce clipping, resulting in a tone rich in harmonics and also in noise, and also producing dynamic range compression and therefore sustain (and sometimes destroying the amplifier). Dave Davies of The Kinks took this technique to its logical conclusion by feeding the output from a 60 watt guitar amplifier directly into the guitar input of a second amplifier.[58] The popularity of these techniques quickly resulted in the development of electronic devices such as the fuzz box to produce similar but more controlled effects and in greater variety.[57] Distortion devices also developed into vocal enhancers, effects units that electronically enhance a vocal performance, including adding air (noise or distortion, or both).[59] Guitar distortion is often accomplished through use of feedback, overdrive, fuzz, and distortion pedals.[60] Distortion pedals produce a crunchier and grittier tone than an overdrive pedal.[60]

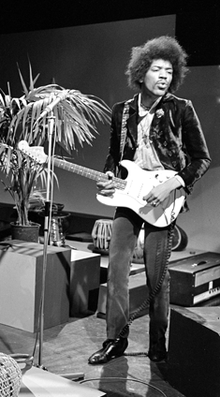

As well as distortion, rock musicians have used audio feedback, which is normally undesirable.[49][61] The use of feedback was pioneered by musicians such as John Lennon of The Beatles,[62][63] Jeff Beck of The Yardbirds, Pete Townshend of The Who, and Jimi Hendrix.[49][64] Hendrix was able to control feedback and turn it into a musical quality,[65] and his use of noise has been described as "sculpted - liquid and fire expertly shaped in mid-air as if by a glass blower."[66] Other techniques used by Hendrix include distortion, wah, fuzz, dissonance, and loud volume.[67]

Jazz

In the mid-1960s, jazz began incorporating elements of rock music,[68] and began using distortion and feedback,[65][69] partially due to the efforts of Jimi Hendrix,[70][71] who had strong links with jazz.[72] The proto-punk band MC5 also used feedback and loudness and was inspired by the avant-garde jazz movement.[68] Jazz musicians who have incorporated noise elements, feedback and distortion include Bill Frisell,[73] David Krakauer[74] Cecil Taylor,[75] Gábor Szabó,[76] Garnett Brown,[77] Grachan Moncur III,[77] Jackie McLean,[78] John Abercrombie,[79][80] John McLaughlin,[81] Joseph Bowie,[77] Larry Coryell,[80] McCo Tyner,[75] Ornette Coleman,[77] Pat Metheny,[82] Phil Minton,[77] Roswell Rudd,[77] and Scott Henderson.[79]

Hip hop

_(5356059653).jpg)

Since its origins in the Bronx during the 1970s, hip hop music has been associated with noise. Author Mark Katz explains that "for the pioneering hip-hop DJs, merely to exist in the Bronx was to experience near-constant noise. But DJs did more than experience noise, they created it, and through their massive sound systems, they indelibly shaped the Bronx soundscape."[83] According to Katz, the use of loud, extravagant sound systems communicated power and territorial control.[84] Furthermore, techniques such as scratching are an expression of transgression. As scratching a record damages it, scratching, like the visual art of graffiti, is a form of vandalism.[85] "It is a celebration of noise," writes Katz, "and no doubt part of the pleasure it brought to DJs came from the knowledge that it annoyed the older generation."[85] Scholar William Jelani Cobb states that "though the genre will always be dismissed by many as brash, monotonous noise, the truth is that hip hop has undergone an astounding array of lyrical and musical transformations."[86] Scholar Ronald Radano writes that "no term in the modern lexicon conveys more vividly African-American music's powers of authenticity and resistance than the figure of 'noise'. In hip-hop parlance, 'noise,' specifically 'black noise', is that special insight from the inside, the anti-philosophy that emerges front and center through the sound attack of rap."[87] Radano finds the appearance of "black noise" nearly everywhere in the "transnational repetitions of rap opposition," but stresses that despite its global nature, black noise still conforms to American racial structures. Radano states that "rather than radicalizing the stable binaries of race, noise inverts them; it transforms prior signs of European musical mastery — harmony, melody, song — into all that is bitchin', kickin', and black."[87]

The hip hop group Public Enemy in particular has been noted for its use of noise in its music. The group's second album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, was backed by the production team The Bomb Squad, who helped craft the album's layered, anti-harmonic, anarchic noise.[88][89] Michael Eric Dyson describes the album as a "powerful mix of music, beats, screams, noise, and rhythms from the streets", and considers it an example of the revival of black radical and nationalist thought.[90] Public Enemy member Chuck D acknowledges that the group's use of noise was an intentional attempt to blur the boundaries between popular music and the noise of everyday life, a decision which writer Jason W. Buel says "ran directly counter to the values of mainstream music of the time."[91] He explains that "without a doubt" this intentional use of noise influenced not only the next decade of hip-hop, but of rock as well.[91] Furthermore, notes Buel, the incorporation of noise served a political function, elevating the ordinary and thus suggesting that common, ordinary people should consider themselves on the same footing as their political and cultural leaders.[91]

Noise as a type of music

Noise music (also referred to simply as noise) has been represented by many genres during the 20th century and subsequently. Some of its proponents reject the attempt to classify it as a single overall genre,[92] preferring to call noise music a non-genre, an aesthetic, or a collection of genres. Even among those who regard it as a genre, its scope is unclear.[93] Some commentators use the phrase "noise music" (or "noise") to refer specifically to Japanese noise music, while others instead use the term Japanoise.[94][95]

While noise music is often nowadays associated with extreme volume and distortion[96] and produced by electronic amplification, the tradition dates back at least to the Futurist Luigi Russolo,[97] who rejected melody, constructed original instruments known as intonarumori and assembled a "noise orchestra" in 1917. It was not well received.[98] In his 1913 manifesto The Art of Noises he observes:

At first the art of music sought purity, limpidity and sweetness of sound. Then different sounds were amalgamated, care being taken, however, to caress the ear with gentle harmonies. Today music, as it becomes continually more complicated, strives to amalgamate the most dissonant, strange and harsh sounds. In this way we come ever closer to noise-sound.[97]

Some types of noise music

- Noise music, abandoning melody, harmony, and sometimes even pulse and rhythm

- Industrial music (1970s)

- Noise rock and noise pop (1980s)

- Japanoise (late 1970s - current)

- Glitch (1990s)

Noise reduction

Most often, musicians are concerned not to produce noise, but to minimise it. Noise reduction is of particular concern in sound recording. This is accomplished by many techniques, including use of low noise components and proprietary noise reducing technologies such as Dolby.[99]

In both recording and in live musical sound reinforcement, the key to noise minimisation is headroom. Headroom can be used either to reduce distortion and audio feedback by keeping signal levels low,[100][101] or to reduce interference, both from outside sources and from the Johnson-Nyquist noise produced in the equipment, by keeping signal levels high.[102] Most proprietary noise reducing technologies also introduce low levels of distortion. Noise minimisation therefore becomes a compromise between interference and distortion, both in recording and in live music, and between interference and feedback in live amplification.[101] The work of Bart Kosko and Sanya Mitaim has also demonstrated that stochastic resonance can be used as a technique in noise minimisation and signal improvement in non-linear dynamical systems, as the addition of noise to a signal can improve the signal-to-noise ratio.[103]

Noise created by mobile phones has become a particular concern in live performances, particularly those being recorded. In one notable incident, maestro Alan Gilbert halted the New York Philharmonic in a performance of Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 9 until an audience member's iPhone was silenced.[104]

Noise as excessive volume

Music played at excessive volumes is often considered a form of noise pollution.[105] Governments such as that of the United Kingdom have local procedures for dealing with noise pollution, including loud music.[106]

Noise as high volume is common for musicians from classical orchestras to rock groups as they are exposed to high decibel ranges.[107][108] Although some rock musicians experience noise-induced hearing loss from their music,[109] it is still debated as to whether classical musicians are exposed to enough high-intensity sound to cause hearing impairments.[110] Nevertheless, in 2008 Trygve Nordwall, the manager of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, invoked new EU rules forbidding more than 85 decibels in the workplace, as a reason for dropping the planned world premiere of Dror Feiler's composition Halat Hisar (State of Siege) because it was "adverse to the health" of the musicians. The twenty-minute piece begins with a burst of machine-gun fire, and gets louder. Readings taken during rehearsals measured at least 130 decibels, and some members of the orchestra reported suffering headaches and permanent tinnitis after sustained exposure for three hours during rehearsals. Earplugs for the musicians were suggested, but they objected they could not hear each other and the composer also rejected the idea, adding that his composition was "no louder than anything by Shostakovich or Wagner".[111]

Music-induced hearing loss is still a controversial topic for hearing researchers.[112] While some studies have shown that the risk for hearing loss increases as music exposure increases, other studies found little to no correlation between the two.[112]

Many bands, primarily in the rock genre, use excessive volumes intentionally. Several bands have set records as the loudest band in the world, with Deep Purple, The Who, and Manowar having received entries in the Guinness Book of World Records.[113][114][115] Other claimants to the title include Motörhead,[114] Led Zeppelin,[116] Blue Cheer,[117][118] Gallows,[119] Bob Dylan's 1965 backing electric band,[120] Grand Funk Railroad,[121] Canned Heat,[118] and the largely fictional parody group Spinal Tap.[122] My Bloody Valentine are known for their "legendarily high" volume concerts,[123] and Sunn O))) are described as surpassing them.[124] The sound levels at Sunn O))) concerts are intentionally loud enough that they are noted for having physical effects on their audience.[125][126]

See also

| Look up noise or music in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Noise in general

- Noise (disambiguation) for a list of other articles related to noise

- Noise (electronics)

Relating noise to music

- The definition of music, detailed discussions

- Phonaesthetics for the aesthetics of sound, and particularly what is meant by cacophony

- Aesthetics of music

- Inharmonicity, one of the factors causing a sound to be perceived as unpitched

- Consonance and dissonance#Dissonance for discussion of the nature and usage of discords in melody and harmony and similar devices in rhythm and metre

- Timbral listening

Related types

Related types of music

- Category:Noise music for an automated list of articles related to noise as a type of music

Notes

- ↑ Attali 1985, 27.

- ↑ Scholes 1970, 10, 686.

- ↑ Reddy, Badami, Balasubramanian 1994, 206.

- ↑ Kosko 2006, 3.

- ↑ Hegarty 2006.

- ↑ Kouvaras 2013.

- ↑ Fink 1981, 25.

- ↑ Nattiez 1990, 48, 55.

- ↑ Helmholtz 1885, 67–68.

- ↑ Maconie 2005, 84.

- ↑ Hopkin 1996, 2, 92.

- ↑ Mathiesen 2001; West 1992, 122.

- ↑ Athenaeus 1854, 3:1015.

- ↑ Livy 1823, 5:297–98.

- ↑ Stillman 2001.

- ↑ Jones 2001.

- ↑ Provine 2001.

- ↑ Qureshi, et al. 2001, §I, 2 (i)

- ↑ Qureshi, et al. 2001, §VII, 1, (d)

- ↑ Qureshi, et al. 2001, §VII, 2, (ii), (a).

- ↑ Pirker 2001.

- ↑ Blades 1996, 265.

- ↑ Meyer 1974, 484–85.

- ↑ Blades 1996, 266–67.

- ↑ Montagu 2002, 108–10.

- ↑ Sachs 2010, 65.

- ↑ Meyer 1974, 486–87.

- ↑ Henck 2004, 32–50.

- ↑ Gates and Higginbotham 2004, 85.

- ↑ Henck 2004, 41–45.

- ↑ Henck 2004, 56; Kimbell 1991, 606.

- ↑ Walls 2001, §2 xi.

- ↑ Newman 1972, 207; Pyron and Bianco 2001.

- ↑ Arnold 1994, 54.

- ↑ Arnold 1994, 56–57.

- 1 2 Hast, Cowdery, and Scott 1999, 149.

- ↑ Arnold 1994, 53.

- ↑ Griffiths 2001.

- ↑ Kennedy 2006.

- ↑ Oechsler 2001.

- ↑ Machlis 1979, 154–56, 357.

- ↑ Miller and Hanson 2001; Holland and Page 2001.

- ↑ Goldman 1961.

- ↑ Varèse and Chou 1966, .

- ↑ Simms 1986, 317.

- ↑ Simms 1986, 319–20.

- ↑ Rhodes and Westwood 2008, 184.

- ↑ Simms 1986, 374.

- 1 2 3 Madden 1999, 92.

- ↑ Stockhausen 1963b, 142 and 144.

- ↑ Stockhausen 1963b, 144–45.

- ↑ Anon. n.d.}

- 1 2 Heller 2003, 197.

- ↑ Fast 2004, 233.

- ↑ Hessler and Lehner 2008, 72.

- ↑ Bacon 1981, 142.

- 1 2 Bacon 1981, 119

- ↑ Piccola 2009.

- ↑ Maserati 2012.

- 1 2 Bennett 2002, 43.

- ↑ Holmes 2008, 186.

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, 136–37.

- ↑ Shea and Rodriguez 2007, 173.

- ↑ Coelho 2003, 116.

- 1 2 Martin and Waters 2011, 323.

- ↑ Stubbs 2003, 6.

- ↑ Candelaria and Kingman 2011, 130.

- 1 2 Kirchner 2005, 505.

- ↑ Dunscomb and Hill 2002, 233.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, 132–33.

- ↑ Bush 2005, 72.

- ↑ Sallis 1996, 155.

- ↑ Ake 2002, 169-170

- ↑ Berendt, Huesmann 2009, 1881.

- 1 2 Dicaire 2006, 233.

- ↑ Tiegal 1967.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Berendt, Huesmann 2009

- ↑ Dicaire 2006, 103.

- 1 2 Bush 2005, 6, 28, 74.

- 1 2 Martin, Waters 2013, 201.

- ↑ Martin, Waters 2013, 203.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, ]98.

- ↑ Katz 2012, 39.

- ↑ Katz 2012, 39-40

- 1 2 Katz 2012, 66.

- ↑ Cobb 2007, 84.

- 1 2 Radano 2000, 39.

- ↑ Cobb 2007, 57.

- ↑ Strong 2002, 854.

- ↑ Dyson 1993, 13.

- 1 2 3 Buel 2013, 118, 120.

- ↑ "With the vast growth of Japanese noise, finally, noise music becomes a genre—a genre that is not one, to paraphrase Luce Irigaray" (Hegarty 2007, 133).

- ↑ Wolf 2009, 67: "The genre noise music does not have a proper definition".

- ↑ Minor 2004, 291.

- ↑ Gottlieb and McLelland 2003, 60.

- ↑ Piekut 2011, 193.

- 1 2 Russolo 1913.

- ↑ Hegarty 2007, 13–14.

- ↑ Dolby Laboratories n.d.

- ↑ Amyes 1998, 60.

- 1 2 Self 2011, 417.

- ↑ Self 2011, 411–29, 510–11.

- ↑ Kosko, Mitaim 1998, 2152.

- ↑ Associated Press 2012.

- ↑ Avison 1989, 469.

- ↑ Directgov

- ↑ Jansson and Karlsson 1983.

- ↑ Maia and Russo 2008,.

- ↑ Anon. 2006b.

- ↑ Ostri, Eller, Dahlin, and Skylv 1989, pp. 243–49

- ↑ Anon. 2008; Connolly 2008.

- 1 2 Morata 2007.

- ↑ Ankeny n.d.

- 1 2 Cohen 1986, 36.

- ↑ Anon. 2009.

- ↑ Kreps 2009.

- ↑ Anon. 2006a, 21.

- 1 2 De la Parra 2000, .

- ↑ Dan 2007.

- ↑ Unterberger 2002, xiii.

- ↑ James 1999, 30.

- ↑ McCreadie 2009, 153.

- ↑ Hughey 2009.

- ↑ Turner 2009.

- ↑ Battaglia 2009.

- ↑ Economy 2004.

References

- Ake, David Andrew. 2002. Jazz Cultures. Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 0520228898.

- Alexander, Charles (ed.). 2003. Masters of Jazz Guitar: The Story of the Players and Their Music. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-87930-728-8.

- Amyes, Tim. 1998. Audio Post-Production in Video and Film. Amsterdam, Oxford, and Waltham, MA: Focal Press/Elsevier. ISBN 0-240-51542-0 (Accessed 3 May 2012).

- Ankeny, Jason. n.d. "Deep Purple". Allmusic (Accessed 24 December 2011).

- Anon. n.d. "A Brief History of Sound Masking". SoundMask UK. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- Anon. 2006a. "Little Steven's Underground Garage:Garage Rock". Billboard 118, no. 22 (3 June): 21 (Accessed 16 May 2012) ISSN 0006-2510.

- Anon. 2006b. "Rock and Roll Hard of Hearing Hall of Fame". Guitar Player. 2006. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012..

- Anon. 2008. "Orchester setzt ohrenbetäubendes Stück ab". Die Welt (6 April).

- Anon. 2009. "Manowar". Music Might. Retrieved 21 April 2012..

- Arnold, Ben. 1994. "War Music and Its Innovations". Music Review 55, no. 1 (February): 52–57.

- Associated Press. 2012. "N. Y. Philharmonic Maestro Stops Performance for Ringing Cell Phone". Richmond Times-Dispatch (12 January) (Accessed 3 May 2012).

- Athenaeus, of Naucratis. 1854 The Deipnosophists, or, Banquet of the Learned of Athenæus, literally translated by Charles Duke Yonge. Bohn's Classical Library 13–15. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Attali, Jacques. 1985. Noise: The Political Economy of Music, translated by Brian Massumi, foreword by Frederic Jameson, afterword by Susan McClary. Theory and History of Literature 16. Manchester: The Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-1470-0 (cloth) ISBN 0-7190-1471-9 (pbk).

- Avison, John. 1989. The World of Physics Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes. ISBN 0-17-438733-4 (Accessed 21 April 2012).

- Bacon, Tony (ed.). 1981. Rock Hardware: The Instruments, Equipment and Technology of Rock (London: New Burlington Books, 1981). ISBN 0-906286-10-7.

- Battaglia, Andy. 2009. "Live Report: Krakow's Unsound Festival". The A.V. Club, (13 November).(Accessed 21 April 2012).

- Bennett, Joe. 2002. Guitar Facts. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-634-05192-0

- Berendt, Joachim-Ernst and Günther Huesmann. 2009. The Jazz Book: From Ragtime to the 21st Century. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 1613746040.

- Blades, James. 1996. Percussion Instruments and Their History, fourth edition, illustrated, revised. Westport, Conn.: Bold Strummer. ISBN 0-933224-71-0 (cloth) ISBN 0-933224-61-3 (pbk).

- Boehmer, Konrad. 1967. Zur Theorie der offenen Form in der neuen Musik. Darmstadt: Edition Tonos.

- Buel, Jason W. 2013. "Chuck D," 100 Entertainers Who Changed America: An Encyclopedia of Pop Culture Luminaries [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Pop Culture Luminaries, edited by Robert C. Sickels. 115-121. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-598-84831-1.

- Bush, André. 2005. Modern Jazz Guitar Styles. Pacific: Mel Bay Publications. ISBN 978-0-7866-5865-7.

- Candelaria, Lorenzo and Daniel Kingman. 2011. American Music: A Panorama. Stamford: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-91612-3.

- Cobb, William Jelani. 2007. To the Break of Dawn: A Freestyle on the Hip Hop Aesthetic. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-814-71725-7.

- Coelho, Victor (ed.). 2003. The Cambridge Companion to the Guitar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00040-6.

- Cohen, Scott. 1986. "Motorhead is the Loudest Band on Earth". Spin 1, no. 10 (February): 36. (Accessed 21 April 2012) ISSN 0886-3032.

- Connolly, Kate. 2008. "New Work Too Loud for Orchestra"". The Guardian (8 April).

- Cott, Jonathan. 1973. Stockhausen: Conversations with the Composer. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Cox, Christoph, and Daniel Warner. 2004. "The Liberation of Sound by Edgard Varèse". In Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music (reprint edition). New York: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-1615-2.

- Dan. 2007. "Gallows Become the World's Loudest Band!", Kerrang! (21 June) (Accessed 15 July 2007). Archived from the original on 26 June 2007.

- De la Parra, Fito, with T. W. McGarry, and Marlane McGarry. 2000. Living the Blues: Canned Heat's Story of Music, Drugs, Death, Sex and Survival . [S.l.]: RUF; London: Turnaround; Nipomo, Calif: Canned Heat Music. ISBN 978-0-9676449-0-5. eBookIt.com (9 June 2011). ISBN 978-1-4566-0332-8.

- Dicaire, David. 2006. Jazz Musicians, 1945 to the Present. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0786485574.

- Directgov. "Dealing with a Noise Nuisance". Government of the United Kingdom. (Accessed 21 April 2012).

- Dolby Laboratories. n.d. "DOLBY B, C, AND S NOISE REDUCTION SYSTEMS: Making Cassettes Sound Better".

- Dunscomb, J. Richard, and Willie L. Hill. 2002. Jazz Pedagogy: The Jazz Educator's Handbook and Resource Guide. Los Angeles: Alfred Music Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7579-9125-7

- Dyson, Michael Eric. 1993. Reflecting Black: African-American Cultural Criticism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-452-90081-0.

- Economy, Jeff. 2004. "Proud SUNN O))) Fills the Air", Chicago Tribune (2 July) (Accessed 21 April 2012).

- Fast, Yvona. 2004. Employment for Individuals with Asperger Syndrome or Non-Verbal Learning Disability: Stories and Strategies. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84310-766-8.

- Fink, Robert. 1981. The Origin of Music: A Theory of the Universal Development of Music. Saskatoon: Greenwich-Meridian. 978-0-9124-2406-4

- Gates, Henry Louis, and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. 2004. "Blind Tom", in African American Lives, 84–86. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516024-X.

- Goldman, Richard Franko. 1961. “Varèse: Ionisation; Density 21.5; Intégrales; Octandre; Hyperprism; Poème Electronique. Instrumentalists, cond. Robert Craft. Columbia MS 6146 (stereo)” (in Reviews of Records). Musical Quarterly 47, no. 1 (January): 133–34.

- Gottlieb, Nanette, and Mark J. McLelland. 2003. Japanese Cybercultures. London and New York: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-27919-2 (Accessed 25 May 2012).

- Griffiths, Paul. 2001. "Sprechgesang". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Hast, Dorothea E., James R. Cowdery, and Stan Scott (eds.). 1999. Exploring the World of Music: An Introduction to Music from a World Music Perspective. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt. ISBN 0-7872-7154-3 (Accessed 19 April 2012).

- Hegarty, Paul. 2008. "Come on, feel the noise". The Guardian. London: Guardian Media Group.

- Hegarty, Paul. 2007. Noise/Music: A History. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Heller, Sharon. 2003. Too Loud, Too Bright, Too Fast, Too Tight: What to Do If You Are Sensory Defensive in an Overstimulating World. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-093292-3.

- Helmholtz, Hermann L. F. 1885. On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music, second English edition, translated by Alexander J. Ellis. London: Longmans & Company. Reprint edition, with a new introduction by Henry Morgenthau, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1954.

- Henck, Herbert. 2004. Klaviercluster: Geschichte, Theorie und Praxis einer Klanggestalt. Signale aus Köln 9. Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 3-8258-7560-1.

- Hessler, Jack R., and Noel D. M. Lehner. 2008. Planning and Designing Research Animal Facilities. Amsterdam, London, Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-369517-8.

- Holland, James, and Janet K. Page. 2001. "Percussion". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Holmes, Thom. 2008. Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture, third edition. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-95781-6

- Hopkin, Bart. 1996. Musical Instrument Design: Practical Information for Instrument Making. Tucson: See Sharp Press. ISBN 978-1-884365-08-9.

- Hughey, Jesse. 2009. "My Bloody Valentine Will Hand Out Free Earplugs Tonight: Use Them", Dallas Observer (22 April) (Accessed 21 April 2012).

- James, Billy. 1999. An American Band: The Story of Grand Funk Railroad. London: SAF Publishing. ISBN 978-0-946719-26-6.

- Jansson, E., and K. Karlsson. 1983. "Sound Levels Recorded Within the Symphony Orchestra and Risk Criteria for Hearing Loss". Scandinavian Audiology 12, no. 3 (1 January): 215–21. doi:10.3109/0105398309076249 (Accessed 19 April 2012).

- Jones, Stephen. 2001. "China: §IV: Living Traditions, 4: Instrumental Music, (i) Ensemble Traditions, (b) Shawm-and-Percussion Bands". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Katz, Mark. 2012. Groove Music: The Art and Culture of the Hip-Hop DJ. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-971605-0.

- Kennedy, Michael. 2006. "Sprechgesang, Sprechstimme". The Oxford Dictionary of Music, second edition, revised, Joyce Bourne, associate editor. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861459-3.

- Kimbell, David. 1991. Italian Opera. Cambridge, New York, and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46643-1.

- Kirchner, Bill (ed.). 2005. The Oxford Companion To Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518359-7.

- Kosko, Bart, Sanya Mitaim. "Adaptive Stochastic Resonance" Proceedings of the IEEE 86, no. 11 (November): 2152-2183.

- Kosko, Bart. 2006. Noise. City of Westminster, London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-67003495-6.

- Kouvaras, Linda Ioanna. 2013. Loading the Silence: Australian Sound Art in the Post-Digital Age. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4724-0035-2.

- Kreps, Daniel. 2009. "'Led Zeppelin II' Turns 40". Rolling Stone (22 October).

- Kurtz, Michael. 1992. Stockhausen: A Biography, translated by Richard Toop. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-17146-X.

- Livy [Titus Livius]. 1823. The History of Rome, first American, from the last London edition, translated by George Baker, in six volumes. Philadelphia: H.C. Carey & I. Lea; Washington: Davis & Force; New York: Peter A. Mesier; Baltimore: F. Lucas; Georgetown: Thomas; Fredericksburg, Va.: William F. Gray.

- Mâche, François-Bernard. 1993. Music, Society and Imagination in Contemporary France. Yverdon: Harwood Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-3-7186-5421-5. (Accessed 6 May 2012)

- MacDonald, Ian. 2005. Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties, third edition. London: Pimlico. ISBN 1-84413-828-3.

- Machlis, Joseph. 1979. Introduction to Contemporary Music, second edition. New York and London: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-09026-4.

- Maconie, Robin. 2005. Other Planets: The Music Of Karlheinz Stockhausen. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5356-0.

- McCreadie, Marsha. 2009. Documentary Superstars: How Today's Filmmakers Are Reinventing the Form. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58115-508-2.

- Madden, Charles B. 1999. Fractals in Music: Introductory Mathematics for Musical Analysis. Salt Lake City: High Art Press. ISBN 978-0-9671727-5-0.

- Maia, Juliana Rollo Fernandes, and Ieda Chaves Pacheco Russo. 2008. "Study of the Hearing of Rock and Roll Musicians", SciFLO Brazil 20, no. 1 (March). . ISSN 0104-5687 doi:10.1590/S0104-56872008000100009 (Accessed 19 April 2012)

- Maserati, Tony. 2012. "Maserati VX1 Vocal Enhancer." Waves Audio. (Accessed 8 April 2012).

- Martin, Henry and Keith Waters. 2013. Essential Jazz. Stamford: Cengage Learning. ISBN 1133964400

- Martin, Henry and Keith Waters. 2011. Jazz: The First 100 Years. Stamford: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4390-8333-8

- Mathiesen, Thomas J. 2001. "Greece, §I: Ancient". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Meyer, Eve R. 1974. "Turquerie and Eighteenth-Century Music". Eighteenth-Century Studies 7, no. 4 (Summer): 474–88.

- Meyer-Eppler, Werner. 1955. "Statistische und psychologische Klangprobleme". Die Reihe 1 "Elektronische Musik": 22–28. English translation by Alexander Goehr, as "Statistic and Psychologic Problems of Sound", in the English edition of Die Reihe 1 "Electronic Music" (1957): 55–61.

- Miller, Leta E., and Charles Hanson. 2001. "Harrison, Lou (Silver)". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Minor, William. 2004. Jazz Journeys to Japan: The Heart Within. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11345-3 (Accessed 25 May 2012).

- Montagu, Jeremy . 2002. Timpani and Percussion. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09337-3 (Accessed 19 April 2012).

- Morata, Thais. 2007. "Young People: Their Noise and Music Exposures and the Risk of Hearing Loss", International Journal of Audiology 46, no. 3:111–12. ISSN 1708-8186, doi:10.1080/14992020601103079

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques. 1990. Music and discourse: toward a Semiology of music, translated by Carolyn Abbate. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02714-5.

- Newman, William S. 1972. The Sonata in the Baroque Era, third edition. The Norton Library. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- Oechsler, Anja. 2001. "Toch, Ernst", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Ostri, B., N. Eller, E. Dahlin, and G. Skylv. 1989. "Hearing Impairment in Orchestral Musicians". International Journal of Audiology 18, no. 4 (1 January). (Accessed 19 April 2012) doi:10.3109/14992028909042202

- Piccola, Derek. 2009. "Guitar Amplification". Mid-term project. Fredonia: State University of New York at Fredonia (Spring) (accessed 13 April 2012).

- Piekut, Benjamin. 2011. Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and Its Limits. California Studies in 20th-Century Music 11. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26850-0 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-520-26851-7 (pbk).

- Pirker, Michael. 2001. "Janissary Music [Turkish Music]". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Potter, Keith. 2001. Four Musical Minimalists: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01501-1 (Accessed 6 May 2012).

- Pritchett, James. 1993. The Music of John Cage. Music in the 20th Century. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41621-3 (cloth); ISBN 0-521-56544-8 (pbk).

- Provine, Robert. C. 2001. "Korea II. Traditional Music Genres: 3. Folk Music", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Pyron, Nona, and Aurelio Bianco. 2001. "Farina, Carlo". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Qureshi, Regula, Harold S. Powers, Jonathan Katz, Richard Widdess, Gordon Geekie, Alastair Dick, Devdan Sen, Nazir A. Jairazbhoy, Peter Manuel, Robert Simon, Joseph J. Palackal, Soniya K. Brar, M. Whitney Kelting, Edward O. Henry, Maria Lord, Alison Arnold, Warren Pinckney, Kapila Vatsyayan, Bonnie C. Wade 2001. "India, Subcontinent of". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Radano, Ronald. 2000. "Black Noise / White Mastery". Decomposition: Post-disciplinary Performance, edited by Sue-Ellen Case, Philip Brett, Susan Leigh Foster. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33723-8

- Reddy, K.R., S. B. Badami, V. Balasubramanian. 1994. Oscillations And Waves. Hyderabad: Universities Press. ISBN 978-8-1737-1018-6.

- Rhodes, Carl, and Robert Ian Westwood. 2008. Critical Representations of Work And Organization in Popular Culture. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35989-4; ISBN 9780203007877.

- Russolo, Luigi. 1913. "L'arte dei Rumori". English version "The Art of Noises", translated by Robert Filliou, published by UbuWeb, 2004. Series editor Michael Tencer. (Accessed 27 May 2012).

- Sachs, Harvey. 2010. The Ninth: Beethoven and the World In 1824. New York: Random House. ISBN 1-4000-6077-X (Accessed 19 April 2012).

- Sallis, James (ed.). 1996. The Guitar in Jazz: An Anthology. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4250-0.

- Scholes, Percy Alfred. 1970. Oxford Companion to Music, tenth edition, revised and reset, edited by John Owen Ward. London and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Self, Douglas. 2011. The Design of Active Crossovers. Amsterdam, Oxford, and Waltham, MA: Focal Press/Elsevier. ISBN 0-240-81738-9.

- Shea, Stuart, and Robert Rodriguez. 2007. Fab Four FAQ: Everything Left to Know about the Beatles—and More! FAQ Series. Milwaukee and New York: Hal Leonard. ISBN 1-4234-2138-8.

- Simms, Bryan R. 1986. Music of the Twentieth Century: Style and Structure. New York: Schirmer Books; London: Collier Macmillan Publishers.

- Slonimsky, Nicolas, Theodore Baker, and Laura Kuhn. 2001. Schirmer Pronouncing Pocket Manual of Musical Terms, fifth edition. New York.: Schirmer; London: Omnibus. ISBN 978-0-8256-7223-1. (Accessed 6 May 2012).

- Stillman, Amy K. 2001. "Polynesia II. Eastern Polynesia, 3. French Polynesia, (i) Society Islands", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Stubbs, David. 2003. Jimi Hendrix: The Stories behind Every Song. Cambridge:Da Capo Press. ISBN 1-56025-537-4. (Accessed 13 April 2012).

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1963a. "… wie die Zeit vergeht …", annotated by Georg Heike. Texte zur Musik 1, edited and with an afterword by Dieter Schnebel, 99–139. DuMont Dokumente. Cologne: Verlag M. DuMont Schauberg.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1963b. "Elektronische und Instrumentale Musik". In his Texte zur Musik 1, edited and with an afterword by Dieter Schnebel, 140–51. DuMont Dolumente. Cologne: Verlag M. DuMont Schauberg. English version as "Electronic and Instrumental Music", translated by Jerome Kohl, with Suzanne Stephens and John McGuire. In Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music, edited by Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner,. New York: Continuum, 2004. ISBN 0-8264-1614-4; ISBN 0-8264-1615-2.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1963c. "Die Einheit der musikalische Zeit". Texte zur Musik 1, edited and with an afterword by Dieter Schnebel, 211–21. DuMont Dokumente. Cologne: Verlag M. DuMont Schauberg.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1989. "Four Criteria of Electronic Music". In Karlheinz Stockhausen, Stockhausen On Music: Lectures and Interviews, compiled by Robin Maconie, 88–111. London and New York: Marion Boyers. ISBN 0-7145-2887-0 (cloth); ISBN 0-7145-2918-4 (pbk).

- Strong, Martin Charles, editor. 2002. The Great Rock Discography, sixth edition. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-841-95312-0.

- Tiegal, Eliot. 1967. "Jazz Beat". Billboard 79, no 23 (10 June): 12. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Turner, Luke, 2009. "Here comes the Sunn O))): Rock's Most Progressive Band". The Guardian (1 July) (Accessed 21 April 2012).

- Unterberger, Richie. 2002. Turn! Turn! Turn!: The '60s Folk-Rock Revolution. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-87930-703-5.

- Varèse, Edgard, and Chou Wen-chung. 1966. "The Liberation of Sound". Perspectives of New Music 5, no. 1 (Autumn–Winter): 11–19.

- Walls, Peter. 2001. "Bow, II: Bowing". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- West, M[artin]. L[itchfield]. 1992. Ancient Greek Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wolf, Motje. 2009. "Thinking About Noise". In Proceedings of Sound, Sight, Space and Play 2009: Postgraduate Symposium for the Creative Sonic Arts, De Montfort University Leicester, United Kingdom, 6–8 May 2009, edited by Motje Wolf, 67–73. Published online (Accessed 19 April 2012).

Further reading

Perception and use of noise in music

- Beament, James. 2001. How We Hear Music: The Relationship Between Music and the Hearing Mechanism. Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-8511-5940-9.

- Demers, Joanna. 2010. Listening through the Noise: The Aesthetics of Experimental Electronic Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1997-7448-7.

- Kahn, Douglas. 1999. Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-2621-1243-7.

- Moravcsik, Michael J. 2001. Musical Sound: An Introduction to the Physics of Music. New York: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-3064-6710-3.

- Priest, Gail. 2009. Experimental Music: Audio Explorations in Australia. Kensington, New South Wales: University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-9214-1007-9.

- Rodgers, Tara, editor. 2010. Pink Noises: Women on Electronic Music and Sound. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-9415-0.

- Voegelin, Salome. 2010. Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. 978-1-4411-6207-6.

- Waksman, Steve. 1999. Instruments of Desire: The Electric Guitar and the Shaping of Musical Experience. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-6740-0547-1.

- Washburne, Christopher, Maiken Derno. 2004. Bad Music: The Music We Love to Hate. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4159-4365-9.

Noise reduction

- Collins, Mike. 2004. Pro Tools for Music Production: Recording, Editing and Mixing. Waltham, Massachusetts: Focal Press. ISBN 978-0-2405-1943-2.

- Hurtig, Brent. 1988. Multi-Track Recording for Musicians. Van Nuys: Alfred Music. ISBN 978-1-4574-2484-7.

- Ingard, Uno. 2010. Noise Reduction Analysis. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-1-9340-1531-5.

- Snoman, Rick. 2012. The Dance Music Manual: Tools, Toys and Techniques. Waltham, Massachusetts: Focal Press. ISBN 978-1-1361-1557-8.

- Vaseghi, Saeed. 2008. Advanced Digital Signal Processing and Noise Reduction. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-4707-4016-3.