Bowel obstruction

| Bowel obstruction | |

|---|---|

| intestinal obstruction | |

|

Upright abdominal X-ray demonstrating a small bowel obstruction. Note multiple air fluid levels. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

| ICD-10 | K56 |

| ICD-9-CM | 560 |

| DiseasesDB | 15838 |

| MedlinePlus | 000260 |

| MeSH | D007415 |

Bowel obstruction, also known as intestinal obstruction, is a mechanical or functional obstruction of the intestines which prevents the normal movement of the products of digestion.[1][2] Either the small bowel or large bowel may be affected.[3] Symptoms include abdominal pain, vomiting, bloating, and not passing gas.[3] Mechanical obstruction is the cause of about 5 to 15% of cases of severe abdominal pain of sudden onset requiring admission to hospital.[3][1]

Causes of bowel obstruction include adhesions, hernias, volvulus, endometriosis, inflammatory bowel disease, appendicitis, tumors, diverticulitis, ischemic bowel, tuberculosis, and intussusception.[3][1] Small bowel obstructions are most often due to adhesions and hernias while large bowel obstructions are most often due to tumors and volvulus.[3][1] The diagnosis may be made on plain X-rays; however, CT scan is more accurate.[3] Ultrasound or MRI may help in the diagnosis of children or pregnant women.[3]

The condition may be treated conservatively or with surgery.[1] Typically intravenous fluids are given, a tube is placed through the nose into the stomach to decompress the intestines, and pain medications are given.[1] Antibiotics are often given.[1] In small bowel obstruction about 25% require surgery.[4] Complications may include sepsis, bowel ischemia, and bowel perforation.[3]

About 2.5 million cases of or bowel obstruction occurred in 2013 which resulted in 236,000 deaths.[5][6] Both sexes are equally affected and the condition can occur at any age.[4] Bowel obstruction has been documented throughout history with cases detailed in the Ebers Papyrus of 1550 BC and by Hippocrates.[7]

Signs and symptoms

|

Tinkly bowel sounds

Tinkly bowel sounds as heard with a stethoscope in someone with a small bowel obstruction. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Depending on the level of obstruction, bowel obstruction can present with abdominal pain, swollen abdomen, abdominal distension, vomiting, fecal vomiting, and constipation.[8]

Bowel obstruction may be complicated by dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities due to vomiting; respiratory compromise from pressure on the diaphragm by a distended abdomen, or aspiration of vomitus; bowel ischaemia or perforation from prolonged distension or pressure from a foreign body.

In small bowel obstruction the pain tends to be colicky (cramping and intermittent) in nature, with spasms lasting a few minutes. The pain tends to be central and mid-abdominal. Vomiting may occur before constipation .

In large bowel obstruction, the pain is felt lower in the abdomen and the spasms last longer. Constipation occurs earlier and vomiting may be less prominent. Proximal obstruction of the large bowel may present as small bowel obstruction.

Causes

Small bowel obstruction

Causes of small bowel obstruction include:[1]

- Adhesions from previous abdominal surgery (most common cause)

- Barbed sutures.[9]

- Pseudoobstruction

- Hernias containing bowel

- Crohn's disease causing adhesions or inflammatory strictures

- Neoplasms, benign or malignant

- Intussusception in children

- Volvulus

- Superior mesenteric artery syndrome, a compression of the duodenum by the superior mesenteric artery and the abdominal aorta

- Ischemic strictures

- Foreign bodies (e.g. gallstones in gallstone ileus, swallowed objects)

- Intestinal atresia

Large bowel obstruction

Causes of large bowel obstruction include:

- Neoplasms

- Diverticulitis / Diverticulosis

- Hernias

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Colonic volvulus (sigmoid, caecal, transverse colon)

- Adhesions

- Constipation

- Fecal impaction

- Fecaloma

- Colon atresia

- Intestinal pseudoobstruction

- Endometriosis

- Narcotic induced (especially with the large doses given to cancer or palliative care patients)

Outlet obstruction

Outlet obstruction is a sub-type of large bowel obstruction and refers to conditions affecting the anorectal region that obstruct defecation, specifically conditions of the pelvic floor and anal sphincters. Outlet obstruction can be classified into 4 groups.[10]

- Functional outlet obstruction

- Inefficient inhibition of the internal anal sphincter

- Short-segment Hirschsprung's disease

- Chagas disease

- Hereditary internal sphincter myopathy

- Inefficient relaxation of the striated pelvic floor muscles

- Anismus (pelvic floor dyssynergia)

- Multiple sclerosis

- Spinal cord lesions

- Inefficient inhibition of the internal anal sphincter

- Mechanical outlet obstruction

- Dissipation of force vector

- Impaired rectal sensitivity

- Megarectum

- Rectal hyposensitivity

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses of bowel obstruction include:

- Ileus

- Pseudo-obstruction or Ogilvie's syndrome

- Intra-abdominal sepsis

- Pneumonia or other systemic illness .

Diagnosis

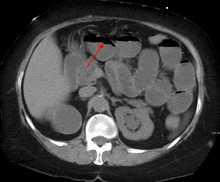

The main diagnostic tools are blood tests, X-rays of the abdomen, CT scanning, and/or ultrasound. If a mass is identified, biopsy may determine the nature of the mass.

Radiological signs of bowel obstruction include bowel distension and the presence of multiple (more than six) gas-fluid levels on supine and erect abdominal radiographs.

Contrast enema or small bowel series or CT scan can be used to define the level of obstruction, whether the obstruction is partial or complete, and to help define the cause of the obstruction.

According to a meta-analysis of prospective studies by the Cochrane Collaboration, the appearance of water-soluble contrast in the cecum on an abdominal radiograph within 24 hours of oral administration predicts resolution of an adhesive small bowel obstruction with a pooled sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 96%.[11]

Colonoscopy, small bowel investigation with ingested camera or push endoscopy, and laparoscopy are other diagnostic options.

Treatment

Some causes of bowel obstruction may resolve spontaneously;[12] many require operative treatment.[13] In adults, frequently the surgical intervention and the treatment of the causative lesion are required. In malignant large bowel obstruction, endoscopically placed self-expanding metal stents may be used to temporarily relieve the obstruction as a bridge to surgery,[14] or as palliation.[15] Diagnosis of the type of bowel obstruction is normally conducted through initial plain radiograph of the abdomen, luminal contrast studies, computed tomography scan, or ultrasonography prior to determining the best type of treatment.[16]

Small bowel obstruction

In the management of small bowel obstructions, a commonly quoted surgical aphorism is: "never let the sun rise or set on small-bowel obstruction"[17] because about 5.5%[17] of small bowel obstructions are ultimately fatal if treatment is delayed. However improvements in radiological imaging of small bowel obstructions allow for confident distinction between simple obstructions, that can be treated conservatively, and obstructions that are surgical emergencies (volvulus, closed-loop obstructions, ischemic bowel, incarcerated hernias, etc.).[1]

A small flexible tube (nasogastric tube) may be inserted from the nose into the stomach to help decompress the dilated bowel. This tube is uncomfortable but does relieve the abdominal cramps, distension and vomiting. Intravenous therapy is utilized and the urine output is monitored with a catheter in the bladder.[18]

Most people with SBO are initially managed conservatively because in many cases, the bowel will open up. Some adhesions loosen up and the obstruction resolves. However, when conservative management is undertaken, the patient is examined several times a day, and X-ray images are obtained to ensure that the individual is not getting clinically worse.[19]

Conservative treatment involves insertion of a nasogastric tube, correction of dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities. Opioid pain relievers may be used for patients with severe pain. Antiemetics may be administered if the patient is vomiting. Adhesive obstructions often settle without surgery. If obstruction is complete a surgery is usually required.

Most patients do improve with conservative care in 2–5 days. However, in some occasions, the cause of obstruction may be a cancer and in such cases, surgery is the only treatment. These individuals undergo surgery where the cause of SBO is removed. Individuals who have bowel resection or lysis of adhesions usually stay in the hospital a few more days until they are able to eat and walk.[20]

Small bowel obstruction caused by Crohn's disease, peritoneal carcinomatosis, sclerosing peritonitis, radiation enteritis, and postpartum bowel obstruction are typically treated conservatively, i.e. without surgery.

Children

Fetal and neonatal bowel obstructions are often caused by an intestinal atresia, where there is a narrowing or absence of a part of the intestine. These atresias are often discovered before birth via a sonogram, and treated with using laparotomy after birth. If the area affected is small, then the surgeon may be able to remove the damaged portion and join the intestine back together. In instances where the narrowing is longer, or the area is damaged and cannot be used for a period of time, a temporary stoma may be placed.

Prognosis

The prognosis for non-ischemic cases of SBO is good with mortality rates of 3-5%, while prognosis for SBO with ischemia is fair with mortality rates as high as 30%.[21]

Cases of SBO related to cancer are more complicated and require additional intervention to address the malignancy, recurrence, and metastasis, and thus are associated with poorer prognosis.

All cases of abdominal surgical intervention are associated with increased risk of future small-bowel obstructions. Statistics from U.S. healthcare report 18.1% re-admittance rate within 30 days for patients who undergo SBO surgery.[22] More than 90% of patients also form adhesions after major abdominal surgery.[23] Common consequences of these adhesions include small-bowel obstruction, chronic abdominal pain, pelvic pain, and infertility.[23]

Other animals

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Fitzgerald, J. Edward F. (2010). Small Bowel Obstruction. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 74–79. doi:10.1002/9781444315172.ch14. ISBN 9781405170253.

- ↑ Adams, James G. (2012). Emergency Medicine: Clinical Essentials (Expert Consult -- Online). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 331. ISBN 1455733946.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Gore, RM; Silvers, RI; Thakrar, KH; Wenzke, DR; Mehta, UK; Newmark, GM; Berlin, JW (November 2015). "Bowel Obstruction.". Radiologic clinics of North America. 53 (6): 1225–40. PMID 26526435.

- 1 2 Ferri, Fred F. (2014). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2015: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1093. ISBN 9780323084307.

- ↑ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, Collaborators (22 August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet (London, England). 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMID 26063472.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (10 January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet (London, England). 385 (9963): 117–71. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ Yeo, Charles J.; McFadden, David W.; Pemberton, John H.; Peters, Jeffrey H.; Matthews, Jeffrey B. (2012). Shackelford's Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1851. ISBN 1455738077.

- ↑ Vann, MPH, Madeline (July 26, 2010). "Diagnosing and Treating Bowel Obstruction". Everyday Health. (Medically reviewed by) Pat F. Bass III, MD, MPH. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ↑ Segura-Sampedro JJ, Ashrafian H, Navarro-Sánchez A, Jenkins JT, Morales-Conde S, Martínez-Isla A (Nov 2015). "Small bowel obstruction due to laparoscopic barbed sutures: An unknown complication?". Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 107 (11): ,. doi:10.17235/reed.2015.3863/2015. PMID 26541657.

- ↑ Wexner, edited by Andrew P. Zbar, Steven D. (2010). Coloproctology. New York: Springer. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-84882-755-4.

- ↑ Abbas, S; Bissett, IP; Parry, BR (January 25, 2005). "Oral water soluble contrast for the management of adhesive small bowel obstruction.". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD004651. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004651.pub2. PMID 15674958.

- ↑ Ludmir, J; P Samuels; BA Armson; MH Torosian (December 1989). "Spontaneous Small Bowel Obstruction Associated With A Spontaneous Triplet Gestation – A Case Report". J Reprod Med. Pub Med. 34 (12): 985–7. PMID 2621741.

- ↑ "Abdominal Adhesions and Bowel Obstruction". University of California San Francisco. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ↑ Young, CJ; MK Suen; J Young; MJ Solomon (October 2011). "Stenting Large Bowel Obstruction Avoids A Stoma: Consecutive Series of 100 Patients". Journal Colorectal Dis. Pub Med. 13 (10): 1138–41. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02432.x. PMID 20874797.

- ↑ P Mosler; KD Mergener; JJ Brandabur; DB Schembre; RA Kozarek (February 2005). "Palliation of Gastric Outlet Obstruction and Proximal Small Bowel Obstruction With Self-Expandable Metal Stents: A Single Center Series". J Clin Gastroenterol. Pub Med. 39 (2): 124–8. PMID 15681907.

- ↑ Holzheimer, Rene G. (2001). Surgical Treatment. NCBI Bookshelf. ISBN 3-88603-714-2.

- 1 2 DD Maglinte; FM Kelvin; MG Rowe MG; GN Bender GN; DM Rouch (January 1, 2001). "Small-bowel obstruction: optimizing radiologic investigation and nonsurgical management". Radiology. 218 (1): 39–46. doi:10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01ja5439. PMID 11152777.

- ↑ Small Bowel Obstruction overview. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ↑ Small Bowel Obstruction:Treating Bowel Adhesions Non-Surgically. Clear Passage treatment center online portal Retrieved February 19, 2010

- ↑ Small Bowel Obstruction The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. February 19, 2010

- ↑ Kakoza, R.; Lieberman, G. (May 2006). "Mechanical Small Bowel Obstruction" (PDF).

- ↑ "Readmissions to U.S. Hospitals by Procedure" (PDF). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- 1 2 Liakakos, T; N Thomakos; PM Fine; C Dervenis; RL Young (2001). "Peritoneal Adhesions: Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Significance". Dig Surgery. Pub Med. 18 (4): 260–273. doi:10.1159/000050149. PMID 11528133.