Out Skerries

| Location | |

|---|---|

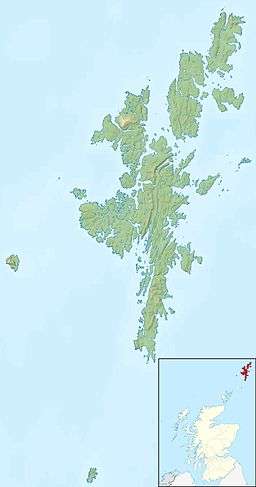

Out Skerries Out Skerries shown within the Shetland Islands | |

| OS grid reference | HU681718 |

| Coordinates | 60°25′N 0°46′W / 60.417°N 0.767°WCoordinates: 60°25′N 0°46′W / 60.417°N 0.767°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Shetland |

| Area | 400 hectares (990 acres)[1] |

| Highest elevation | Bruray Wart 43 metres (141 ft)[2] |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Shetland Islands Council |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 76[3] |

The Out Skerries are an archipelago in Shetland, Scotland, lying to the east of the main Shetland Island group. Locally, they are usually called Da Skerries or just Skerries.[4]

Geography

The Out Skerries lie about four miles north east of Whalsay and Bound Skerry forms the easternmost part of Scotland, lying 320 kilometres (200 mi) from Norway. The main islands are Housay, Bruray and Grunay.

A large number of islets and stacks surround the main group. These include the Hevda Skerries and Wether Holm to the north, the Holm to the south and Lamba Stack and Flat Lamba Stack to the east. Stoura Stack and the Hogg are to the south of Grunay. Bound Skerry, which has a lighthouse, is flanked by Little Bound Skerry and Horn Skerry.

Beyond Mio Ness at the south west tip of Housay are North and South Benelip and the Easter Skerries, as well as Filla, Short & Long Guen (the Guens), Bilia Skerry, and Swaba Stack. In an isolated group between the main Out Skerries and the Mainland, are Little Skerry and the Vongs, and Muckle Skerry is another outlier lying further north.

Etymology

Most of the Skerries placenames have a Norse origin. The "Out" name derives from one or both of two Old Norse words. Austr means "east" and may have been used to distinguish Out Skerries from Ve Skerries or "west skerries", and utsker means "outer".[5] "Skerry" is from the Old Norse sker and refers to a small rocky island or a rocky reef.

Housay is from the Old Norse Húsey meaning "horse island"[6] although this name is now little used by locals, who prefer "West Isle".[7] Bruray may be from the Norse brú and mean "bridge island" due to its position between West Isle and Grunay, the latter meaning simply "green island". The derivation of Bound Skerry is more problematic but may be from bønn, meaning "forerunner", a reference to this being the first land a ship encounters en route to Shetland from Bergen.[8]

History

Prehistory

There is evidence of Neolithic inhabitation including two house sites at Queyness.[9] The Battle Pund is a 13 metres (43 ft) across rectangle marked out by boulders dating from the Bronze Age. It is similar to a structure at Hjaltadans in Fetlar, but its purpose is unknown.[10]

There is a massive ruined structure on the north shore of Grunay known locally as "the broch" although it is not known if it dates from the Iron Age, when such structures were built throughout the far north of Scotland. The name "Benelips" possibly originating from the Old Norse bon meaning "to pray" hints at the existence of an early Christian hermitage on these remote islets.[11]

Dey (1991) speculates that the folklore of the troll-like trows, and perhaps that of the selkie may be based in part on the Norse invasions of the Northern Isles. She states that the conquest by the Vikings sent the indigenous, dark-haired Picts into hiding and that "many stories exist in Shetland of these strange people, smaller and darker than the tall, blond Vikings who, having been driven off their land into sea caves, emerged at night to steal from the new land owners." The skerry of Trollsholm and its cleft of Trolli Geo indicate the presence of this folklore on Out Skerries.[12]

Historic period

The Out Skerries have been permanently inhabited from the Norse period onwards.

There are a number of shipwrecks around the islands include the Dutch vessels Kemmerland (1664) and De Leifde (1711); and North Wind (1906), which was carrying wood which was salvaged and used by the islanders for their houses.[13] Some of the gold from these wrecks was found in 1960.[14]

Due to their remote and rugged nature, the islanders were accused of smuggling and wrecking.[14] Tammy Tyrie's Hidey Hol was used by islanders to avoid press gangs.[14]

Until the early 20th century, a lot of haaf fishing was conducted from sixareens.[15]

World War II

Being so close to Norway, the islands were of strategic importance in World War II and were a regular landfall for Norwegian boats carrying escapees from the Nazi occupation. The local coastguard were responsible for the refugees and at one point during the war were issued with a tommy gun, although initially no-one knew how to use it. German planes frequently flew over at low altitudes, strafing the Grunay lighthouse shore station in 1941 and dropping a bomb in 1942. The latter attack killed Mary Anderson, the only local casualty of the war and Grunay was evacuated shortly thereafter.[16] A month later a Canadian bomber crashed on Grunay and in 1990, a plaque was raised to commemorate this event.[17] Dey (1991) states that the bomber was a "British" Blenheim bomber with a crew of two Canadians and one Englishman. The plaque ceremony was attended by the family of F/Sgt Jay Oliver, one of the two Canadian casualties and Peter Johnson, a local man who had witnessed the crash aged eight years.[18] During the war an official letter was sent in secret to the local sub-postmistress with instructions that it be opened in the event of a German invasion. After the war it was returned, unopened.[18]

Population

The population of the Out Skerries is 76, and lives entirely on Housay and Bruray, which are linked by a bridge. The population is around half what it was in the mid-19th century. Only one child lives on Out Skerries, who became known on the Internet as the only student of his school.

Economy and transport

The soil in the islands is thin and infertile, but is heaped into riggs, for better cultivation of potatoes, carrots and swedes.[13] Sheep farming still occurs, but is far less important than it once was.[13] Tourism on the other hand has increased.[13]

The islands have a primary school, two shops, a fish processing factory, an airstrip, and a church, and a police station. The previously open secondary school was the smallest in the UK; in 2010 the school had only three pupils. The secondary school was closed in 2014 by the approval of the Scottish government.[19] The primary school in 2015 had just one pupil.[20] The main industry on the islands is fishing. There is a church on Housay.

There is little peat on the Out Skerries, so the residents have been granted rights to cut it on Whalsay.[6]

The Skerries Bridge, which links Bruray to Housay was built in 1957, replacing the first bridge built in 1899.[6]

There is around a mile of road, along which most of the population lives.

There is a ferry to the islands from Vidlin and Lerwick.

References

- ↑ "Out Skerries - Nearest to Norway" visitshetland.com. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "Get-a-Map". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- ↑ "Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands" (28 November 2003) General Register Office for Scotland. Edinburgh. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- ↑ "Out Skerries" Shetlopedia. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- ↑ Dey (1991) p. 120

- 1 2 3 Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 459-461

- ↑ Dey (1991) p. 1

- ↑ Dey (1991) pp. 121-23

- ↑ Dey (1991) p. 10. The Ordnance Survey call this area on the west coast of Housay "Queyin Ness"

- ↑ Dey (1991) p. 11

- ↑ Dey (1991) pp. 11-12

- ↑ Dey (1991) p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sea & Land". Shetland Heritage. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Smugglers & Treasure". Shetland Heritage. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ↑ "Safe Haven". Shetland Heritage. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ↑ Dey (1991) pp. 87-88

- ↑ "Historical Heritage". Shetland Heritage. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- 1 2 Dey (1991) p. 89

- ↑ Carrell, Severin (22 January 2014). "Shetland families furious over decision to shut Out Skerries school". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ↑ Wace, Charlotte (22 November 2015). "In a class of his own". Mail Online. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

Further reading

- Dey, Joan (1991). Out Skerries - an Island Community. Lerwick: The Shetland Times. ISBN 0-900662-74-3.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Out Skerries. |