Palladium hydride

Palladium hydride is metallic palladium that contains a substantial quantity of hydrogen within its crystal lattice. Despite its name, it is not an ionic hydride but rather an alloy of palladium with metallic hydrogen. At room temperature, palladium hydrides may contain two crystalline phases, α and β (sometimes called α'). Pure α phase exists at x < 0.017 whereas pure β phase is realised for x > 0.58; intermediate x values correspond to α-β mixtures.[1]

Hydrogen absorption by palladium is reversible and therefore has been investigated for hydrogen storage.[2] Palladium electrodes have been used in some cold fusion experiments, under the hypothesis that the hydrogen could be "squeezed" between the palladium atoms to help them fuse at lower temperatures than would otherwise be required. A great number of research labs in the United States, Italy, Japan, Israel, Korea, China and elsewhere claim to have observed cold fusion in palladium deuteride (heavy hydrogen version of palladium hydride).[3]

History

The absorption of hydrogen gas by palladium was first noted by T. Graham in 1866 and absorption of electrolytically produced hydrogen, where hydrogen was absorbed into a palladium cathode, was first documented in 1939.[2] Graham produced an alloy with the composition PdH0.75.[4]

Chemical structure and properties

Palladium is sometimes metaphorically called a "metal sponge" (not to be confused with more literal metal sponges) because it soaks up hydrogen "like a sponge soaks up water". At room temperature and atmospheric pressure (standard ambient temperature and pressure), palladium can absorb up to 900 times its own volume of hydrogen.[5] As of 1995, hydrogen can be absorbed into the metal-hydride and then desorbed back out for thousands of cycles. Researchers look for ways to extend the useful life of palladium storage.[6]

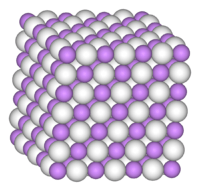

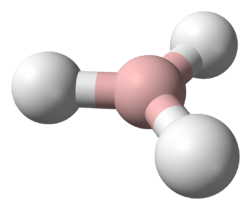

The absorption of hydrogen produces two different phases, both of which contain palladium metal atoms in a face centered cubic (fcc, rocksalt) lattice, which is the same structure as pure palladium metal. At low concentrations up to PdH0.02 the palladium lattice expands slightly, from 3.889 Å to 3.895 Å. Above this concentration the second phase appears with a lattice constant of 4.025 Å. Both phases coexist until a composition of PdH0.58 when the alpha phase disappears.[1] Neutron diffraction studies have shown that hydrogen atoms randomly occupy the octahedral interstices in the metal lattice (in an fcc lattice there is one octahedral hole per metal atom). The limit of absorption at normal pressures is PdH0.7, indicating that approximately 70% of the octahedral holes are occupied. The absorption of hydrogen is reversible, and hydrogen rapidly diffuses through the metal lattice. Metallic conductivity reduces as hydrogen is absorbed, until at around PdH0.5 the solid becomes a semiconductor.[4]

Superconductivity

PdHx is a superconductor with a transition temperature Tc of about 9 K for x=1. (Pure palladium is not superconducting). Drops in resistivity vs. temperature curves were observed at higher temperatures (up to 273 K) in hydrogen-rich (x ~ 1), nonstoichiometric palladium hydride and interpreted as superconducting transitions.[7][8][9] These results have been questioned[10] and have not been confirmed thus far.

Surface absorption process

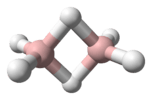

The process of absorption of hydrogen has been shown by scanning tunnelling microscopy to require aggregates of at least three vacancies on the surface of the crystal to promote the dissociation of the hydrogen molecule.[11] The reason for such a behaviour and the particular structure of trimers has been analyzed.[12]

Uses

The absorption of hydrogen is reversible and is highly selective. Industrially a palladium-based diffuser separator is used. Impure gas is passed through tubes of thin walled silver-palladium alloy. Protium and deuterium readily diffuse through the alloy membrane. The gas that comes through is pure and ready for use. Palladium is alloyed with silver to improve its strength. To ensure that the formation of the beta phase is avoided, as the lattice expansion noted earlier would cause distortions and splitting of the membrane, the temperature is maintained above 300 °C.[4]

See also

References

- 1 2 Manchester, F. D.; San-Martin, A.; Pitre, J. M. (1994). "The H-Pd (hydrogen-palladium) System". Journal of Phase Equilibria. 15: 62. doi:10.1007/BF02667685. Phase diagram for Palladium-Hydrogen System

- 1 2 W. Grochala; P. P. Edwards (2004). "Thermal Decomposition of the Non-Interstitial Hydrides for the Storage and Production of Hydrogen". Chem. Rev. 104 (3): 1283–1316. doi:10.1021/cr030691s. PMID 15008624.

- ↑ LENR phenomenom at nasa

- 1 2 3 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 1150–151. ISBN 0-08-037941-9.

- ↑ Ralph Wolf; Khalid Mansour. "The Amazing Metal Sponge: Soaking Up Hydrogen". 1995.

- ↑ "Extending the Life of Palladium Beds".

- ↑ Tripodi, P (2003). "Possibility of high temperature superconducting phases in PdH" (PDF). Physica C. 388–389: 571–572. Bibcode:2003PhyC..388..571T. doi:10.1016/S0921-4534(02)02745-4.

- ↑ Tripodi, P; Digioacchino, D; Vinko, J (2004). "Superconductivity in PdH: phenomenological explanation". Physica C: Superconductivity. 408-410: 350. Bibcode:2004PhyC..408..350T. doi:10.1016/j.physc.2004.02.099.

- ↑ Tripodi, Paolo; Di Gioacchino, Daniele; Vinko, Jenny Darja (2007). "A review of high temperature superconducting property of PdH system". International Journal of Modern Physics B. 21 (18&19): 3343–3347. Bibcode:2007IJMPB..21.3343T. doi:10.1142/S0217979207044524.

- ↑ Baranowski, B.; Dębowska, L. (2007). "Remarks on superconductivity in PdH" (PDF). Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 437: L4. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2006.07.082.

- ↑ T. Mitsui, M. K. Rose, E. Fomin, D. F. Ogletree & M. Salmeron (2003). "Dissociative hydrogen adsorption on palladium requires aggregates of three or more vacancies". Nature. 422 (6933): 705–7. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..705M. doi:10.1038/nature01557. PMID 12700757.

- ↑ N. Lopez, Z. Lodziana, F. Illas & M. Salmeron (2004). "When Langmuir is too simple: H2 dissociation on Pd(111)". Physical Review Letters. 93 (14): 146103. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..93n6103L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.146103.

External links

- The Purification of Hydrogen. Platinum Metals Review

- PhD thesis

- Electrochimica Acta