Palmanova

| Palmanova | |

|---|---|

| Comune | |

| Città di Palmanova | |

|

Aerial view of Palmanova | |

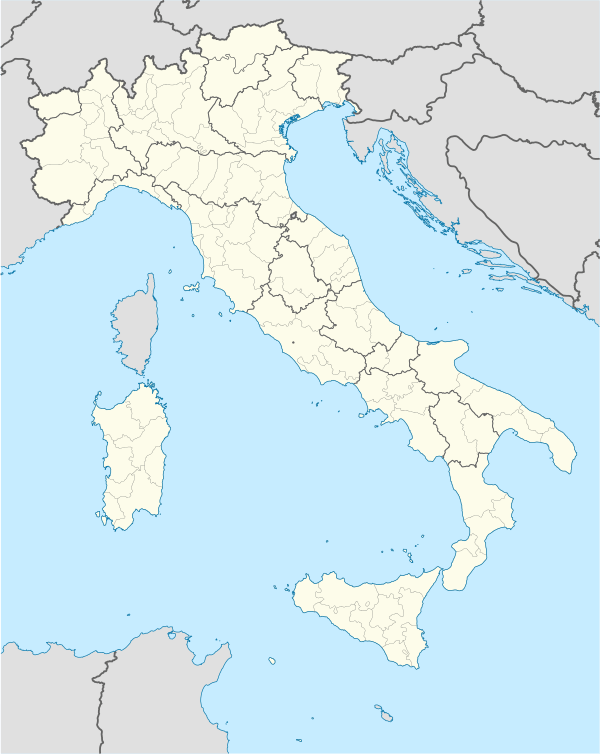

Palmanova Location of Palmanova in Italy | |

| Coordinates: 45°54′N 13°19′E / 45.900°N 13.317°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Friuli-Venezia Giulia |

| Province / Metropolitan city | Udine (UD) |

| Frazioni | Jalmicco, Sottoselva, San Marco |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Francesco Martines |

| Area | |

| • Total | 13.32 km2 (5.14 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 27 m (89 ft) |

| Population (21 December 2009) | |

| • Total | 5,406 |

| • Density | 410/km2 (1,100/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Palmarini |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) |

| Postal code | 33057 |

| Dialing code | 0432 |

| Patron saint | Justina of Padua |

| Saint day | October 7 |

| Website | Official website |

Palmanova (Friulian: Palme) is a town and comune in northeastern Italy. The town is an excellent example of star fort of the Late Renaissance, built up by the Venetians in 1593.

Geography

Located in the southeast part of the autonomous region Friuli-Venezia Giulia, it is 20 kilometres (12 mi) from Udine, 28 kilometres (17 mi) from Gorizia and 55 kilometres (34 mi) from Trieste, near the junction of the motorways A23 and A4.

History

On 7 October 1593, the superintendent of the Republic of Venice founded a revolutionary new kind of settlement: Palmanova. The city’s founding date commemorated the victory of the Christian forces (supplied primarily by the Italian states and the Spanish kingdom) over the Ottoman Turks in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, during the War of Cyprus. Also honored on 7 October was Saint Justina, chosen as the city’s patron saint. Using all the latest military innovations of the 16th century, this small town was a fortress in the shape of a nine-pointed star, designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi. Between the points of the star, ramparts protruded so that the points could defend each other. A moat surrounded the town, and three large, guarded gates allowed entry. The construction of the first circle, with a total circumference of 7 kilometres (4 mi), took 30 years. Marcantonio Barbaro headed a group of Venetian noblemen in charge of building the town, Marcantonio Martinego was in charge of construction, and Giulio Savorgnan acted as an adviser.[1] A second phase of construction took place between 1658 and 1690, and the outer line of fortifications was completed between 1806 and 1813 under the Napoleonic domination. The final fortress consists of: 9 ravelins, 9 bastions, 9 lunettes, and 18 cavaliers. In 1815 the city came under Austrian rule until 1866, when it was annexed to Italy together with Veneto and the western Friuli. In 1960 Palmanova was declared a national monument.

American professor Edward Wallace Muir Jr. said on Palmanova: "The humanist theorists of the ideal city designed numerous planned cities that look intriguing on paper but were not especially successful as livable spaces. Along the northeastern frontier of their mainland empire, the Venetians began to build in 1593 the best example of a Renaissance planned town: Palmanova, a fortress city designed to defend against attacks from the Ottomans in Bosnia. Built ex nihilo according to humanist and military specifications, Palmanova was supposed to be inhabited by self-sustaining merchants, craftsmen, and farmers. However, despite the pristine conditions and elegant layout of the new city, no one chose to move there, and by 1622 Venice was forced to pardon criminals and offer them free building lots and materials if they would agree to settle the town."[2]

Ideal city of the Renaissance

Palmanova was built following the ideals of a utopia. It is a concentric city with the form of a star, with three nine-sided ring roads intersecting in the main military radiating streets. It was built at the end of the 16th century by the Venetian Republic which was, at the time, a major center of trade. It is actually considered to be a fort, or citadel, because the military architect Giulio Savorgnan designed it to be a Venetian military station on the eastern frontier as protection from the Ottoman Empire.

During the renaissance many ideas of a utopia, both as a society and as a city, surfaced. Utopia was considered to be a place where there was perfection in the whole of its society. This idea was started by Sir Thomas More, when he wrote the book Utopia. The book described the physical features of a city as well as the life of the people who lived in it. His book sparked a flame in literary circles. A great many other books of similar nature were written in short order. They all followed a major theme: equality. Everyone had the same amount of wealth, respect, and life experiences. The society had a calculated elimination of variety and a monotonous environment. The city where they lived was always geometric in shape, and was surrounded by a wall. These walls provided military strength, but also protected the city by preserving and passing on man’s knowledge. The knowledge, learning and science gave form to the daily life of the people living inside the walls. The knowledge of each person was shared by the entire society, and there was no way to let any information either in or out. As Thomas More said in his book, "He that knows one knows them all, they are so alike one another."

Alberti, followed by Filarete, were the first to develop the ideas of Utopia into the plan of a city. Filarete designed a concentric city, with peaks and radiating streets, which he called Sforzinda. His geometry was the imitation of a schema representing the work. It is believed to have derived from two overlaying squares. Sforzinda later became the most influential plan in the design of Palmanova. Since Palmanova was built during the renaissance, it imposed geometrical harmony and followed the idea that beauty reinforces the wellness of a society. Each road and move was carefully calibrated and each part of the plan had a reason for being. Each person would have the same amount of responsibility and land, and each person had to serve a specific purpose. The concentric shape was the most prominent design move, and had many reasons for being.

The circular shape of Palmanova was greatly influenced by the fact that it needed to be a fort. At the time of its construction, many other urban theoreticians found the checkerboard was more useful, but it could not provide the protection that military architects desired. The walls of a practical fort are run at angles so that enemy soldiers could not approach it easily because the angles made it possible to establish overlapping fields of fire.

Main sights

Cathedral

The cathedral is located in front of the town hall of Palmanova (formerly the Palace of Provveditore). Commissioned in 1603, the construction started later that year under Inspector Girolamo Cappello, and was completed in 1636. The identities of any architects are uncertain, but may have been Vincenzo Scamozzi and Baldassare Longhena. The cathedral was not consecrated until 1777, after the town had been included into the Archbishopric of Udine.

The bell tower of the cathedral, erected in 1776, was deliberately made short because enemies attacking the city should not be able to see the cathedral from outside the city walls.

The niches in the façade contain statues representing the saints Justina of Padua, one of Padua's patron saints, and Mark, as well as a statue of Christ, the Redeemer. The façade itself is made of stone from Istria, and was restored in 2000.

Other

- The three monumental gates Porta Udine, Porta Cividale and Porta Aquileia.

- The Piazza Grande, to which all the main edifices of the city open, built in Istrian stone.

- The singer Sting gave an outdoor concert in Palmanova's main piazza on 5 July 2001[3]

Transport

Palmanova can be reached from the nearby motorways, A23 (Udine-Tarvisio) and A4 (Turin-Trieste) and by the railway between Udine and Cervignano[4][5] There are also bus connections.

See also

References

- ↑ “Renaissance war studies”, John Rigby Hale, London Hambledon Press, 1983, pg. 185 ISBN 0-907628-02-8

- ↑ Muir, Edward (2007). The culture wars of the late Renaissance : skeptics, libertines, and opera. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. xiii, 175 p. : ill. ; 22 cm. ISBN 978-0-674-02481-6.

- ↑ Show Date: July 05, 2001 / Location: Palmanova / Venue: Piazza Grande / Tour: Brand New Day 1999/01, exclusives.tours, Sting.com. Archived August 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ it:Ferrovia Udine-Cervignano

- ↑ Sito Ufficiale del Comune di Palmanova : Comune di Palmanova

- Hale, J R. “Palmanova: analisio di una citta fortalezza.” Burlington Magazine, 1984, 447. Vol. 126 No. 9762

- Rowe, Collin. The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays. The MIT Press, 1982. pg 206-211

- Rowe, Collin. The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays. 206-211

- Bierman, Judah. PMLA. Science and Society in the New Atlantis and Other Renaissance Utopias. Vol. 78, MLA, 1963. pg. 492-500

- Lang, S. “Sforzinda, Filarete, and Filelfo.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 35, (1972): 391-397. Warlburg Institute

- de la Croix, Horst. “Military Architecture and the Radial City Plan in Sixteenth Century Italy.” The Art Bulletin 42, no. 4 (1960): 263-290. College Art Association

- Lang, S. “Sforzinda, Filarete, and Filelfo.” 391-397

- Rowe, Collin. The Mathematics if the Ideal Villa and Other Essays. 206-211

- Rowe, Collin. The Mathematics if the Ideal Villa and Other Essays. 206-211

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palmanova. |

- "Palmanova, Italy". NASA Earth Observatory newsroom. Retrieved 2004-04-28.

- "Palmanova, Italy". Google Maps. Retrieved 2006-10-05.

- Palmanova medieval festival (photo)

- Official website of the City

Coordinates: 45°54′19.45″N 13°18′35.92″E / 45.9054028°N 13.3099778°E