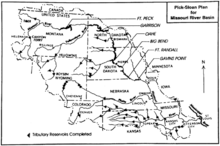

Pick–Sloan Missouri Basin Program

The Pick–Sloan Missouri Basin Program, formerly called the Missouri River Basin Project, was initially authorized by the Flood Control Act of 1944, which approved the plan for the conservation, control, and use of water resources in the Missouri River Basin.

The intended beneficial uses of these water resources include flood control, aids to navigation, irrigation, supplemental water supply, power generation, municipal and industrial water supplies, stream-pollution abatement, sediment control, preservation and enhancement of fish and wildlife, and creation of recreation opportunities.

It derives its name from the authors of the program -- Lewis A. Pick, director of the Missouri River office of the United States Army Corps of Engineers, and William Glenn Sloan, director of the Billings, Montana office of the United States Bureau of Reclamation.[1]

History

The Pick Plan

In May 1943, the House Flood Control Committee chose the United States Army Corps of Engineers to create a solution for extreme flooding in the Missouri Basin. Lewis A. Pick developed a proposal for the corps called the Pick Plan, which was finished in August of the same year.[2]

The Pick Plan introduced three different projects to be carried out by the Army Corps of Engineers. The first undertaking involved the construction of 1,500 miles of levees from Sioux City to the Mississippi River to protect from Missouri River flooding. The second proposal called for the construction of eighteen dams on the Missouri's tributaries. Eleven of those dams had been previously approved by Congress. Five dams were planned to be located on tributaries of the Republican River in the lower basin. Of the remaining dams, the Pick Plan recommended construction of one on the Bighorn River in Wyoming and another on Montana's Yellowstone River. The Pick Plan's third project was the creation of five multi-purpose dams on the Missouri River. Initially, the plan's total cost was estimated to be $490 million.[2]

The original Pick Plan was supported by the National Rivers and Harbors Congress, the Mississippi Valley Association, the Propeller Club of the United States, the American Merchant Marine Conference, the Mississippi Valley Flood Control Association, and other lower-basin residents. Senators Joseph O'Mahoney and Eugene Millikin offered amendments to the plan that would also provide for the interests of people in the upper basin. The amendments created an emphasis on irrigation over river navigation and gave precedence to arid states for the use of basin water. O'Mahoney and Millikin's amendments also called for Congress to inform any states associated with proposed watershed development. The amendments were later added to the Pick Plan.[2]

The Sloan Plan

The Sloan Plan was developed by William G. Sloan, the assistant director at the Bureau of Reclamation's regional office who had previously worked for the Corps of Engineers. The plan was submitted on May 4, 1944 to Congress.

In contrast to the Pick Plan, Sloan's strategy was more intricate. His 211-page program involved plans for ninety irrigation and power development projects. It was proposed with a budget of $1.26 billion.[3] The Sloan Plan pushed for reservoir storage in upper tributaries of the Missouri River located in smaller dams, which would provide irrigation for 4.8 million acres in areas where the land suffered from drought.[2] The Sloan Plan allotted 1.3 million acres of irrigated land in North Dakota. South Dakota, Montana, and Nebraska were allotted about 1 million acres each.[4]

The plan picked up support from the National Reclamation Association and the National Grange.[2]

The Omaha Conference

On October 17, 1944, the Omaha Conference was scheduled for the consolidation of the Pick and Sloan plans. In total, the plans had proposed 113 different projects. Once the plans were merged, 107 of those projects remained. The combined Pick-Sloan Plan allowed the Corps of Engineers jurisdiction over flood control, navigation projects and five main-stem dams. The Bureau of Reclamation was granted permission to build 27 dams in the Yellowstone Basin. In addition, the Corps of Engineers and the Reclamation Bureau were both given authority to develop hydroelectric power on the Missouri River.[2]

The newly merged Pick Sloan Plan was accepted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944. It was officially titled as the Missouri River Basin Development Program and was presented in conjunction with the Flood Control Act of 1944. President Roosevelt authorized $200 million for the program. In its entirety, the Pick-Sloan Plan arranged for 107 dams, 1,500 miles of protective levees, 4.7 million acres of irrigation systems, and 1.6 million kilowatts of electric power.[3]

Early Critics

Many early critics of the Pick-Sloan plan were in favor of creating a Missouri Valley Authority (MVA). They claimed that the MVA would provide a more unified solution to water development on the Missouri River than the merged ideas of opposing bureaucracies. Ideas for the MVA were influenced by the success of the Tennessee Valley Authority. Senator James E. Murray of Montana and Congressman John J. Cochran from Missouri developed bills for the Missouri Valley Authority. The MVA bills planned to navigate the Missouri into a number of stairstep lakes linked together by locks. They would also arrange for giant reservoirs to supply irrigation and cheap hydroelectricity power, arguing that this would produce more public power and leave less condemned private land.[5] The bills were presented in the 79th congress, but they were later brought down.

Interventions

Several water-control measures were introduced through this legislation that variously affected the Missouri River Valley and its environs. They include:

- Fort Peck Dam

- Garrison Dam and Lake Sakakawea

- Oahe Dam

- Big Bend Dam

- Fort Randall Dam

- Gavins Point Dam and Lewis and Clark Lake

- Pick-Sloan Legislation

- Davis Creek Dam

- Virginia Smith Dam

Native American relocation

Over 200,000 acres on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation and the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota were flooded by the Oahe Dam, forcing Native Americans to relocate from flooded areas.[6] In South Dakota, politicians and other proponents of the Pick-Sloan Program and dam construction had promised 1 million acres of irrigation as “appropriate compensation” for lost land.[4] As of 2016, poverty remains a problem for the displaced populations in the Dakotas, who are still seeking compensation for the loss of the towns submerged under Lake Oahe, and the loss of their traditional ways of life.[6]

The construction of main-stream dams also affected other Native American tribes living along the Missouri River on the Fort Berthold, Cheyenne River, Standing Rock, Crow Creek, and Lower Brule Indian reservations. The Garrison, Oahe, and Fort Randall dams created a reservoir that eliminated 90 percent of timber and 75 percent of wildlife on the reservations.[7]

References

- ↑ Bureau of Reclamation (July 29, 2004) Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin Program

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jr, Michael L. Lawson ; foreword by Vine Deloria, (1982). Dammed Indians : the Pick-Sloan plan and the Missouri River Sioux, 1944-1980 (1st ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma press. ISBN 0806116579.

- 1 2 McGovern, Michael L. Lawson ; forewords by George; Jr, Vine Deloria, (2009). Dammed Indians revisited : the continuing history of the Pick-Sloan Plan and the Missouri River Sioux. Pierre: South Dakota State Historical Society Press. ISBN 9780979894015.

- 1 2 Carrels, Peter (1999). Uphill against water : the great Dakota water war. Lincoln [u.a.]: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 080326397X.

- ↑ Campbell, David C. (6 January 2016). "The Pick-Sloan Program: A Case of Bureaucratic Economic Power". Journal of Economic Issues. 18 (2): 449–456. doi:10.1080/00213624.1984.11504244.

- 1 2 Lee, Trymaine. "No Man's Land: The Last Tribes of the Plains. As industry closes in, Native Americans fight for dignity and natural resources". MSNBC - Geography of Poverty Northwest. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

- ↑ Shanks, Bernard D. (1974-06-01). "The American Indian and Missouri River Water Developments1". JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association. 10 (3): 573–579. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.1974.tb00598.x. ISSN 1752-1688.