Progress Party (Norway)

Progress Party Fremskrittspartiet | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Abbreviation | FrP |

| Leader | Siv Jensen |

| Parliamentary leader | Harald T. Nesvik |

| Founded | 8 April 1973 |

| Headquarters |

Karl Johans gate 25 0159 Oslo |

| Newspaper | Fremskritt |

| Youth wing | Progress Party’s Youth |

| Membership | 16,342 (2014)[1] |

| Ideology |

Conservative liberalism[2][3] Economic liberalism[4][5][6] Right-wing populism[3] Euroscepticism[7] |

| Political position | Right-wing[8][9][10] |

| European affiliation | None |

| International affiliation | None |

| Colours | Blue (dark blue) |

| Storting |

29 / 169 |

| County Councils[11] |

83 / 728 |

| Municipal Councils[12] |

889 / 10,781 |

| Sami Parliament[13] |

2 / 39 |

| Website | |

| frp.no | |

The Progress Party (Bokmål: Fremskrittspartiet, Nynorsk: Framstegspartiet, FrP) is a political party in Norway which identifies as classical liberal (libertarian) and conservative-liberal.[14][15] Academics broadly categorise the party as neoliberal (moderate or non-radical) populist,[16][17][18] while the party itself, Norway's Prime Minister Erna Solberg, centrist parties, and some scholars reject any comparison with foreign right-wing populist parties.[19][20][21][22][23] In coalition with the Conservative Party, the party won the 2013 parliamentary election and entered into its first ever government.[24]

Founded by Anders Lange in 1973 as an anti-tax protest movement, the party values individual freedom strongly, supports market liberalism, and advocates downsizing bureaucracy and the public sector, while also proposing increased spending of Norway's public Oil Fund to invest in infrastructure, rejecting the notion of the "budgetary rule".[5][25] The party also seek a more restrictive immigration policy and tougher integration and law and order measures. In foreign policy it is strongly Atlanticist, and pro-globalization. After being neutral on Norwegian membership in the European Union for many years, the party in 2016 officially adopted a position opposing Norwegian membership.[7] Long-time chairman Carl I. Hagen was from 1978 to 2006 the undisputed leader of the party, and in many ways personally controlled the ideology and direction of the party; most notably demonstrated by effectively expelling the most radical libertarian faction in 1994, and anti-immigration populists in 2001.[26][27] The current leader of the party is Siv Jensen, who since 2013 is also Norway's Minister of Finance.

The party became the second largest party in Norway for the first time in the 1997 parliamentary election, a position it also held following the elections in 2005 and 2009; in 2013 it dropped to third largest. The other parties in parliament historically refused any formal governmental cooperation with the Progress Party, but after a long period of work to unite the political right in Norway, helped by Siv Jensen devising a more moderate liberal leadership,[28][29][30] the party entered into a coalition with the Conservative Party, which from 2013 makes up the current Norwegian government (with parliamentary support from two smaller centrist parties).

History

Anders Lange's Party

The Progress Party was founded at a meeting at the movie theater Saga Kino in Oslo on 8 April 1973,[31] attended by around 1,345 persons.[31] The address was held by Anders Lange, after whom the party was named Anders Lange's Party for a Strong Reduction in Taxes, Duties and Public Intervention, commonly known as Anders Lange's Party, and abbreviated ALP.[32] Lange had some political experience from the interwar era Fatherland League, and was part of the Norwegian resistance movement during the Second World War.[31] Since the end of the war, he had worked as an independent right-wing political editor and public speaker.[31] Lange held his first public speech as chairman of ALP at Youngstorget in Oslo on 16 May the same year. ALP was to a large extent inspired by the Danish Progress Party,[33] which was founded by Mogens Glistrup. Glistrup also spoke at the event, which gathered around 4,000 attendees.[34]

Originally, Anders Lange wanted the party to be an anti-tax protest movement rather than a common political party. The party had a brief political platform on a single sheet of paper that on one side listed ten things the party was "tired of", and on the other side ten things that they were in favour of.[35] The protest was directed against what Lange claimed to be an unacceptable high level of taxes, subsidies, and foreign aid.[36] In the 1973 parliamentary election, the party won 5 percent of the vote and gained four seats in the Norwegian parliament. The main reasons for the success has later been seen by scholars as a mixture of tax protests, the charisma of Anders Lange, the role of television, the aftermath of the 1972 EC membership referendum and the political development in Denmark.[37] The first party conference was held in Hjelmeland in 1974, where the party established its first political conventions.[38]

Progress Party and Carl I. Hagen

In early 1974, Kristofer Almås, Deputy Member of Parliament Carl I. Hagen, along with some others, broke away and formed the short-lived Reform Party.[39] The background for this was a criticism of ALPs "undemocratic organisation" and lack of a real party program. However, in the same year, Anders Lange died; consequently Hagen stepped in as a regular Member of Parliament in Lange's place. As a result, the Reform Party merged back into ALP already the following year. The party adopted its current name, the Progress Party, on 29 January 1977, inspired by the great success of the Danish Progress Party.[40] The Progress Party performed poorly in the 1977 parliamentary election, and was left without parliamentary representation. In the 1978 party convention, Carl I. Hagen was elected as party chairman. Hagen soon started to expand the political program of the party, and built a conventional party organisation, a step which Lange and some of his followers had opposed.[31][41] The party's youth organisation, the Progress Party's Youth, was also established in 1978.[42] Hagen succeeded in sharpening the image of the party as an anti-tax movement. His criticism of the wisdom of hoarding billions of dollars in the "Oil Fund" hit a nerve owing to perceived declines in infrastructure, schools, and social services and long queues at hospitals.[43]

1980s: Establishing the party

While the Progress Party dropped out of parliament altogether in 1977, it returned in the following 1981 parliamentary election with four representatives. In this election, the political right in general had a great upturn, which garnered the Progress Party increased support.[42] The ideology of the party was sharpened in the 1980s, and the party officially declared that it was a libertarian party at its national convention in Sandefjord in 1983.[44][45] Until then, the party had not had a clearly defined ideology.[46] In the campaign for the 1985 parliamentary election the party attacked many aspects of the Norwegian welfare state, and campaigned for privatization of medical care, education and government-owned enterprises, as well as steep cuts in income tax.[47] In the election, the party lost two of its four members of parliament, but was left with some power as they became the kingmaker. In May 1986, the party used this position to effectively throw the governing Conservative-led government after it had proposed to increase gas taxes. A minority Labour government was established as a result.[39]

The first real breakthrough for the party in Norwegian politics came in the 1987 local elections, when the party nearly doubled its support from 6.3% to 12.3% (county results). This was largely as immigration was for the first time seriously taken up as an issue by the party (although Hagen had already in the late 1970s called for a strongly restrictive immigration policy),[43] successfully putting the issue on the national agenda.[48] Its campaign had mainly been focused on the issue of asylum seekers,[49] but was additionally helped by the infamous "Mustafa-letter", a letter read out by Hagen during the electoral campaign that portrayed the future Islamisation of Norway.[39][50] In April 1988 the party was for the first time the second largest party in Norway in an opinion poll with 23.5%.[42] In September 1988, the party further proposed in parliament for a referendum on the immigration policy, which was regarded by political scientists as the start of the party's 1989 election campaign.[51] In 1989, the party made its breakthrough in national politics. In the 1989 parliamentary election, the party obtained 13%, up from 3.7% in 1985, and became the third largest party in Norway. It started to gain power in some local administrations. The first mayors from the party were[52] Håkon Rege in Sola (1988–1989),[53] Bjørn Bråthen in Råde (1990–1991)[54] and Peter N. Myhre in Oslo (1990–1991).[55]

1990s: Libertarian schism, consolidation

The 1993 parliamentary election halved the party's support to 6.3% and ten members of parliament. This drop in support can be seen as the result of an internal conflict within the party that came to a head in 1992, between the more radical libertarian minority and the majority led by Carl I. Hagen.[56][57] The libertarians had removed the party's focus on immigration, declaring it a "non-issue" in the early 1990s, which was heavily punished by voters in 1993, as well as 1991.[58] Social conservative policy platforms had also been liberalised and caused controversy, such as accepting homosexual partnership.[59] The party's unclear stance on Norwegian membership of the European Union also contributed greatly to the setback, by moving the focus away from the party's stronger issues (see also Norwegian European Union membership referendum, 1994).[60]

While many of the libertarians, including Pål Atle Skjervengen and Tor Mikkel Wara, had left the party before the 1993 election[42] or had been rejected by voters,[61] the conflict finally culminated in 1994. Following the party conference at Bolkesjø Hotell in Telemark in April of that year, four MPs of the "libertarian wing" in the party broke off as independents. This was because Hagen had given them an ultimatum to adhere to the political line of the party majority and parliamentary group, or else to leave.[42] This incident was later nicknamed "Dolkesjø", a pun on the name of the hotel, with "dolke" meaning to "lit. stab (in the back) /betray".[62]

These events have been seen by political scientists as a turning point for the party.[63] Subsequently the libertarians founded a libertarian organisation called the Free Democrats which tried to establish a political party, but without success. Parts of the younger management of the party and the more libertarian youth organisation of the party also broke away, and even tried to disestablish the entire youth organisation.[64] The youth organisation was however soon running again, this time with more "loyal" members, although it remained more libertarian than its mother organisation. After this, the Progress Party had a more right-wing populist profile, which resulted in it gaining electoral support.[40]

In the 1995 local elections the Progress Party regained the level of support seen at the 1987 elections. This was said largely to have been as a result of a focus on Progress Party core issues in the electoral campaign, especially immigration, as well as the party dominating the media picture as a result of the controversy around the 1995 Norwegian Association meeting at Godlia kino.[65][66] The latter particularly gained the party many sympathy votes, as a result of the harsh media storm targeted against Hagen.[67] In the 1997 parliamentary election, the party obtained 15.3% of the vote, and for the first time became the second largest political party in Norway. The 1999 local elections resulted in the party's first mayor as a direct result of an election, Terje Søviknes in Os. 20 municipalities also elected a deputy mayor from the Progress Party.

2000/01: Turmoil, expulsion of populists

While the Progress Party had witnessed close to 35% support in opinion polls in late 2000,[68] its support fell back to 1997 levels in the upcoming election in 2001. This was largely a result of turmoil surrounding the party. The party's deputy leader Terje Søviknes became involved in a sex scandal, and internal political conflicts came to the surface;[69] Hagen had already in 1999 tried to quiet the most controversial immigration opponents in the parliamentary party, who had gained influence since the 1994 national convention.[27] In late 2000 and early 2001, opposition to this locally in Oslo, Hordaland and Vest-Agder sometimes resulted in expulsions of local representatives.[27] Eventually Hagen also, in various ways, got rid of the so-called "gang of seven" (syverbanden), which consisted of seven members of parliament.[70] In January 2001, Hagen claimed that he had seen a pattern where these had cooperated on several issues,[71] and postulated that they were behind a conspiracy to eventually get Øystein Hedstrøm elected as party chairman.[72] The seven were eventually suspended, excluded from or voluntarily left the party, starting in early 2001.[40] They most notably included Vidar Kleppe (the alleged "leader"), Dag Danielsen, Fridtjof Frank Gundersen, as well as Jan Simonsen.[70] Only Hedstrøm remained in the party, but was subsequently kept away from publicly discussing immigration issues.[73]

This again caused turmoil within the party; supporters of the excluded members criticized their treatment, some resigned from the party,[74] and some of the party's local chapters were closed.[75] Some of the outcasts ran for office in the 2001 election in several new county lists, and later some formed a new party called the Democrats, with Kleppe as chairman and Simonsen as deputy chairman. Though the "gang of seven" took controversial positions on immigration, the actions taken against them were also based on internal issues;[68][76] it remains unclear to what degree the settlement was based primarily on political disagreements or tactical considerations.[77] Hagen's main goal with the "purge" was an attempt to make it possible for non-socialist parties to cooperate in an eventual government together with the Progress Party.[40] In 2007, he revealed that he had received "clear signals" from politicians in among other the Christian Democratic Party, that government negotiations were out of the question so long as certain specific Progress Party politicians, including Kleppe and Simonsen (but not Hedstrøm), remained in the party.[78] The more moderate libertarian minority in Oslo, including Henning Holstad, Svenn Kristiansen and Siv Jensen, now improved their hold in the party.[79]

2001–05: Bondevik II years

In the 2001 parliamentary election the party lost the gains it had made according to opinion polling but maintained its position from the 1997 election, it got 14.6% and 26 members in the parliament. The election result allowed them to unseat the Labour Party government of Jens Stoltenberg and replace it with a three-party coalition led by Christian Democrat Kjell Magne Bondevik. However, the coalition continued to decline to govern together with the Progress Party as they considered the political differences too large. The Progress Party eventually decided to tolerate the coalition, as it promised to invest more in defence, open more private hospitals and open for more competition in the public sector.[80] In 2002 the Progress Party again advanced in the opinion polls and for a while became the largest party.[81][82]

The local elections of 2003 were a success for the party. In 36 municipalities, the party gained more votes than any other; it succeeded in electing the mayor in only 13 of these,[83] but also secured 40 deputy mayor positions.[84] The Progress Party had participated in local elections since 1975, but until 2003 had only secured a mayoral position four times, all on separate occasions. The Progress Party vote in Os—the only municipality that elected a Progress Party mayor in 1999—increased from 36.6% in 1999 to 45.7% in 2003. The party also became the single largest in the counties of Vestfold and Rogaland.[85]

In the 2005 parliamentary elections, the party again became the second largest party in the Norwegian parliament, with 22.1% of the votes and 38 seats, a major increase from 2001. Although the centre-right government of Bondevik which the Progress Party had tolerated since 2001 was beaten by the leftist Red-Green Coalition, Hagen had before the election said that his party would no longer accept Bondevik as Prime Minister, following his consistent refusal to formally include the Progress Party in government.[86][87] For the first time the party was also successful in getting Members of Parliament elected from all counties of Norway, and even became the largest party in three: Vest-Agder, Rogaland and Møre og Romsdal.[40] After the parliamentary elections in 2005, the party also became the largest party in many opinion polls. The Progress Party led November 2006 opinion polls with a support of 32.9% of respondents, and it continued to poll above 25 percent during the following years.[88][89][90][91]

2006–present: Siv Jensen

In 2006, after 27 years as leader of the party, Hagen stepped down to become Vice President of the Norwegian parliament Stortinget. Siv Jensen was chosen as his successor, with the hope that she could increase the party's appeal to voters, build bridges to liberal conservative parties, and head or participate in a future government of Norway. Following the local elections of 2007, Progress Party candidates became mayor in 17 municipalities, seven of these continuing on from 2003. Deputy mayors for the party however decreased to 33.[92] The party in general strongly increased its support in municipalities where the mayor had been elected from the Progress Party in 2003.[93] The best result came in Nordreisa, where the party held the mayor from the last election, with an increase from 24.6% to 49.3%.[92]

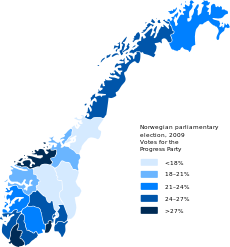

In the months before the 2009 parliamentary elections, the party had, as in the 2001 election, rated very highly in opinion poll results which however declined towards the actual election. Earlier in the year, the Progress Party had achieved above 30% in some polls which made it the largest party by several percentage points.[94] With such high gains, the election result was in this case relatively disappointing. Before the election the gains continued to decrease, with most of these losses going to the Conservative Party which had a surprisingly successful campaign.[95] The decline in support over a longer period of time can also be seen as the Labour Party was since 2008 accused of "stealing" policies from the Progress Party.[96][97] The Progress Party did, regardless, achieve a slight gain from the 2005 election with 22.9%, the best election result in the party's history. It also for the first time got represented in the Sami Parliament of Norway in 2009, with three representatives.[98] This made it the fourth largest party in the Sami parliament, and second largest of the nationwide parties. In the informal school elections in Norway, the party became the largest party in Norway with 24% of the votes.[99]

Since early 2010, opinion polls regularly showed a majority support for the Progress Party and Conservative Party together.[100][101][102][103] The Progress Party however saw a strong setback for the 2011 local elections. The party lost 6% in vote share, while the Conservative Party gained 9%. According to political scientists, most of the setback could be explained by a low turnout of Progress Party supporters.[104][105]

In coalition with the Conservative Party, the party won the 2013 parliamentary election and helped form its first ever government, the Solberg's Cabinet, although the Progress Party itself lost seats and is now the third largest party instead of the second largest.[24][28]

Isolation

Ever since its foundation, other parties have consistently refused the Progress Party's efforts to join any governing coalition at the state level. The reasons have mainly included concerns about the party's alleged irresponsibility and its position on immigration issues.[83] Following the increased support and importance of the Progress Party in the 2005 elections, the Conservative Party stated they wanted to be "a bridge between the Progress Party and the centre." This is because the centrist Liberal Party[106] and Christian Democratic Party[107] reject the possibility of participating in a government coalition together with the Progress Party. In addition, the Progress Party does not want to support a government coalition that it itself is not a part of.[108] In 2010, the Conservative Party went even further when its leader Erna Solberg stated that the Progress Party was now such a big party that it "must" be part of any centre-right governmental negotiations after the 2013 elections.[109] At the municipal level, the Progress Party however cooperates with most parties, including the Labour Party.[110] In 2007 it also attracted some unusual attention when the local Porsgrunn Progress Party was involved in some limited cooperation with the Socialist Left Party and the Red Party.[111]

Ideology

The Progress Party currently regards itself to be a "liberal people's party", and its ideology to be classical liberalism[32] or conservative liberalism.[112] The party identifies itself in the preamble of its platform as a liberal (liberalistisk; "liberal, libertarian")[113] party, built on Norwegian and Western traditions and cultural heritage, with a basis in a Christian understanding of life and humanist values.[114] Its main declared goal is a strong reduction in taxes and government intervention.[114] The party is today considered to be conservative liberal,[2] but has sometimes been described as populist.[115] While more fundamental libertarianism was earlier a component of its ideology, this has in practice gradually more or less vanished from the party.[116] As of the late 2000s, the party has also been influenced by Thatcherism, particularly with Siv Jensen becoming party leader.[117]

The core issues for the party revolve around immigration, crime, foreign aid, the elderly and social security in regards to health and care for the elderly. The party is regarded as having policies on the right in most of these cases, both fiscally and socially, though in some cases, like care for the elderly, the policy is regarded as being on the left.[118] It has been claimed that the party changed in its first three decades, in turn from an "outsider movement" in the 1970s, to libertarianism in the 1980s, to right-wing populism in the 1990s.[63][119] From the 2000s, the party has to some extent sought to moderate its profile in order to seek government cooperation with centre-right parties.[120] This has been especially true since the expulsion of certain members around 2001, and further under the lead of Siv Jensen from 2006,[121] when the party has tried to move and position itself more towards conservatism and also seek cooperation with such parties abroad.[112]

Economy

The party is strongly individualistic, wanting to reduce the power of the state and the public sector. It believes that the public sector should only be there to secure a minimum standard of living, and that individuals, businesses and organisations should take care of various tasks instead of the public sector, in most cases. The party also generally advocates the lowering of taxes, various duties, as well increased market economy.[25]

The party also notably want to invest more of Norway's oil wealth in infrastructure (particularly roads, broadband capacity, hospitals, schools and nursing homes) and the welfare state.[122][123] This position, that has used a sense of a welfare crisis to support demands to spend more of the oil fund now rather than later, is part of its electoral success.[83]

The party wants to strongly reduce taxation in Norway, and says that the money Norwegians earn, is theirs to be kept. They want to remove inheritance tax and property tax.[122]

Society

In schools, the party wants to improve the working environment for teachers and students by focusing more on order, discipline and class management. The party wants more individual adaptation, to implement grades in basic subjects from fifth grade, open more private schools and decrease the amount of theory in vocational educations.[124]

The party regards the family to be a natural, necessary and basic element in a free society. It regards the family to be a carrier of traditions and culture, and to have a role in raising and caring for children. The party also wants all children to have a right of visitation and care from both parents, and to secure everyones right to know who their biological parents are.[125] The party opposed the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2008,[126][127][128] questioning how children would "cope" with the law.[129]

During the national convention in May 2013, the party voted in favor of both same-sex marriage and same-sex adoption.[130][131][132] The party has for several years been a proponent for legalizing blood donation for homosexuals.[133][134]

The party believes that artists should be less dependent on public support, and instead be more dependent on making a living on what they create. The party believes that regular people should rather decide what good culture is, and demands that artists on public support should offer something the audience wants. It also wants to abolish the annual fee for the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation and privatise the company. Otherwise, the party wants to protect and secure Norwegian cultural heritage.[135]

Since the party distances itself from discrimination and special treatment based on gender, religion and ethnic origin, the party wants to dissolve the Sami Parliament of Norway, which is based on ethnic classifications.[136] The party wants to uphold Sami culture, but wants to work against any special treatment based on ethnic origin regarding the right of use of water and land.[137]

Populism

The Progress Party has historically sometimes been portrayed externally as a populist or right-wing populist party (or other similar terms),[138] both by opposing politicians,[139] as well as some scholars.[140][141] Depending on definitions of populism, other scholars have however found that populism is at best a minor element of the party,[142] or that its policies historically have been more consistent than for instance those of the Labour Party, which has moved more towards the Progress Party and neoliberalism since the 1980s.[143] Political scientist Anders Todal Jensen has argued that the Progress Party is the only populist party in Norway, with all the other parties in contrast having strong elitist foundations.[144] He has suggested that populism could actually be a sign of health as the structures of the traditional parties make them poorly able to “listen to the people” in the same manner that the Progress Party may.[144]

Law and order

The party supports an increase in police forces, and more visible police on the streets. It wants to implement tougher punishments, especially for crime regarding violence and morality offences. The party also wants to establish an ombudsman for victims and relatives, as it believes today's supportive concern focus too much on the criminals rather than the victims. It wants the police to be able to use more non-lethal weapons, such as electroshock weapons. It also does not accept any use of religious or political symbols with the police uniform, and wants to expel foreign citizens who are convicted of crime with a frame of more than three months imprisonment.[145]

Immigration

From the second half of the 1980s the economic and welfare aspects of immigration policy were mainly a focus of Progress Party criticism,[46] including the strains placed by immigration on the welfare state.[146] During the 1990s the party shifted to focus more on cultural and ethnic issues and conflicts,[147][148] a development which can also be seen in the general public debate, including among its political opponents.[146] In 1993, it was the first party in Norway to use the notion of "integration politics" in its party programme.[50] While the party has made numerous proposals on immigration in parliament, it has rarely received majority support for them.[141] Its proposals has largely been rejected by the remaining political parties, as well as the mass media.[83] Although the party's immigration policies have been compared to those of the Danish People's Party and the Sweden Democrats, leading party members have rather seen its immigration policies to resemble those of the Dutch People's Party for Freedom and Democracy and the Danish Venstre, when those parties were in government.[149]

Generally, the party wants a stricter immigration policy, so that only those who are in need of protection according to the UN Refugee Convention are allowed to stay in Norway.[150] In a speech in the 2007 election campaign, Siv Jensen claimed that the immigration policy was a failure because it let criminals stay in Norway, while throwing out people who worked hard and followed the law.[151] The party claims the immigration and integration policy to be naïve.[150] In 2009, the party proposed an official goal of reducing accepted asylum seekers by about 90%, from 1,000 to 100 a month, the standards then said to be used in Denmark and Finland,[152] although less than 100 a year was proposed in 2008.[153] In 2008, the party wanted to "avoid illiterates and other poorly resourced groups who we see are not able to adapt in Norway"; which included countries as Somalia, Afghanistan and Pakistan.[153] The party opposes that asylum seekers are allowed stay in Norway on humanitarian grounds or due to health issues, and seeks to substantially limit the number of family reunifications.[153] The party has also called for a referendum on the general immigration policy.[51][154][155]

A poll conducted by Utrop in August 2009 showed that 10% (14% if the respondents answering "Don't know" are removed) of immigrants in Norway would vote for the Progress Party, only beaten by the Labour Party (38% and 56% respectively), when asked.[156] More specifically, this constituted 9% of both African and Eastern European immigrants, 22% of Western European immigrants and 3% of Asian immigrants.[157] Thus, it was above all immigrants from Western countries that contributed to the Progress Party, whereas those from Asia were very unlikely to support it; however, many immigrants from Africa also voted for the Progress Party.[156] Individuals of immigrant background are increasingly active in the party, most notably Iranian-Norwegian Mazyar Keshvari and the current leader of the youth party, Indian-Norwegian Himanshu Gulati.[158][159]

Foreign policy

The Progress Party was for many years open to a referendum on Norwegian membership of the European Union, although only if a majority of the public opinion was seen to favour it beforehand.[160] The party eventually grew to consider membership of Norway in the European Union to be a "non-issue", believing there to be no reason for a debate of a new referendum.[161] In 2016, the party officially adopted a position against Norwegian membership in the EU.[7] The party regards NATO to be a positive basic element of Norway's defense, security and foreign policy. It also wants to strengthen transatlantic relations in general, and Norway's relationship with the United States more specifically.[162] The party considers its international policy to "follow in the footsteps of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher."[163]

Of all the major political parties in Norway, the Progress Party has shown the strongest support for Israel. Recently, it has supported the right of Israel to defend itself against rocket attacks from Hamas,[164] and was the only party in Norway which supported Israel through the Gaza War (2008–09).[165][166] The party also wants to relocate the Norwegian embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.[167][168]

The party sees the most viable form of foreign aid policy, to be for developing countries to gradually manage themselves without Western aid. It believes that free trade is the key for developing countries to gain economic growth, and that "the relationship between aid and development is at best unclear." The party is strongly critical of "forced contribution to government development aid through taxation", which it wants to limit, also as it believe this weakens the individual's personal sense of responsibility and generosity (voluntary aid). The party instead supports an increase in support for global health and vaccination initiatives against global epidemics such as HIV, AIDS and tuberculosis, and to increase the support after emergencies and disasters.[169]

International relations

The Progress Party does not belong to any international political groups, and does not have any official sister parties. Historically the party has not compared itself to other European parties, and has sought to rather establish its own identity.[170] In 2008 however, the party for the first time set out to build its international reputation by hiring two international secretaries to travel internationally and establishing contact with politicians and parties abroad. This was cited especially to "not risk being declared as extremists by opponents the day we form a government".[171] An international secretary for the party in the same year said that the party had been connected with a "misunderstood right-wing radical label", partly because people with nationalistic and "hopeless attitudes" had previously been involved in the party. Such persons were said no longer to be involved.[112]

Denmark

The Progress Party was originally inspired by its Danish counterpart, the Progress Party, which ultimately declined, lost parliamentary representation, and fell into the fringes of Danish politics. In recent years, the Norwegian party has rather considered Denmark's Venstre to be its sister party.[172] Formally, Venstre is aligned with the Norwegian Liberal Party, and as late as 2006 the international secretary of Venstre said that "we have nothing in common with the Norwegian Progress Party". In 2009 however, the prominent Venstre MP Inger Støjberg gave her support for the Progress Party, saying there were "great similarities" between the parties,[173] and that Venstre stood "shoulder to shoulder" with the Progress Party, although this position was not supported by Venstre's party chairman Lars Løkke Rasmussen.[174][175]

The party has also been compared to the more national conservative Danish People's Party (DF), with journalist Lars Halskov suggesting that the great support for the party resulted from a combination of the immigration policies of the DF and the liberalism of Venstre.[176] Political scientist Cas Mudde has also regarded the Progress Party to be somewhere in between these two parties.[170] Kristian Norheim, the international secretary for the Progress Party, in 2008 however distanced himself from DF, citing a right-turn in its immigration policy, and left-turn in its financial policies to be problematic.[112] In 2007, Norheim also claimed that the Progress Party were "globalisation friendly", in contrast to DF, and that DF ideologically and politically was in Norway rather comparable to the Democrats.[177]

Other

The Progress Party has by some been compared to parties such as the Dutch Pim Fortuyn List, French Front National and the Freedom Party of Austria.[141] It has been approached for cooperation by some of these parties, including the Belgian Vlaams Belang,[176] French Front National and the Freedom Party of Austria, only to be rejected by the Progress Party.[170] In 2008, the Progress Party international secretary Kristian Norheim specifically distanced the Progress Party from such parties.[112] He regarded many of these parties to be "national social democratic", and stressed their lack of liberalism as inconsistent with the Progress Party's platform.[170] The Progress Party has also been compared to the Alternative for Germany by Jan Simonsen, who he also cited as a blending of conservatives and economic liberals.[178]

The Progress Party mentions among parties it consider itself closest to internationally the Danish Venstre (Liberal Party), the Estonian Reform Party, the Dutch People's Party for Freedom and Democracy, the British Conservative Party and the Czech Civic Democratic Party.[163] In 2009 the British Conservative Party invited party leader Siv Jensen to hold a lecture in the House of Commons, which was seen as a further recognition of the party internationally, with the approach by the Danish Venstre the previous month.[179]

In the United States, the Progress Party generally supports the Republican Party, and was in 2010 called "friends" by the Republican Party chairman as he said he looked forward to the continued growth of the party and free market conservative principles.[180] For the 2008 US election, a survey found that the vast majority of Progress Party MPs and county leaders supported Republican Party candidates for president, although a few individuals supported Democratic Party candidates.[181][182] The party also has some connections with the American Tea Party movement.[183][184][185]

Party leadership

Party leaders

- Anders Lange (1973–1974)

- Eivind Eckbo (1974–1975) (interim)

- Arve Lønnum (1975–1978)

- Carl I. Hagen (1978–2006)

- Siv Jensen (2006–)

Parliamentary leaders

- Anders Lange (1973–1974)

- Erik Gjems-Onstad (1974–1976)

- Harald Bjarne Slettebø (1976–1977)

- Carl I. Hagen (1981–2005)

- Siv Jensen (2005–2013)

- Harald T. Nesvik (2013–)

Deputy party leaders

|

First deputy leaders

|

Second deputy leaders

|

Election results

Parliamentary elections

| Date | Votes | Seats | Position | Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | ± pp | # | ± | |||

| 1973 | 107,784 | 5.0% | + 5.0 | 4 / 155 |

|

Opposition | 6th |

| 1977 | 43,351 | 1.9% | - 3.1 | 0 / 155 |

|

7th | |

| 1981 | 109,564 | 4.5% | + 2.6 | 4 / 155 |

|

Opposition | 5th |

| 1985 | 96,797 | 3.7% | - 0.8 | 2 / 157 |

|

Opposition | 6th |

| 1989 | 345,185 | 13.0% | + 9.3 | 22 / 165 |

|

Opposition | 3rd |

| 1993 | 154,497 | 6.3% | - 6.7 | 10 / 165 |

|

Opposition | 6th |

| 1997 | 395,376 | 15.3% | + 9.0 | 25 / 165 |

|

Opposition | 2nd |

| 2001 | 369,236 | 14.6% | - 0.7 | 26 / 165 |

|

Opposition | 3rd |

| 2005 | 582,284 | 22.1% | + 7.5 | 38 / 169 |

|

Opposition | 2nd |

| 2009 | 614,724 | 22.9% | + 0.8 | 41 / 169 |

|

Opposition | 2nd |

| 2013 | 463,560 | 16.3% | - 6.6 | 29 / 169 |

|

Government | 3rd |

Local elections

| Year | Vote (county) | Vote (municipal) | Party leader |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | 1.4% |

0.8% |

Eivind Eckbo |

| 1979 | 2.5% |

1.9% |

Carl I. Hagen |

| 1983 | 6.3% |

5.3% |

Carl I. Hagen |

| 1987 | 12.3% |

10.4% |

Carl I. Hagen |

| 1991 | 7.0% |

6.5% |

Carl I. Hagen |

| 1995 | 12.0% |

10.5% |

Carl I. Hagen |

| 1999 | 13.4% |

12.1% |

Carl I. Hagen |

| 2003 | 17.9% |

16.4% |

Carl I. Hagen |

| 2007 | 18.5% |

17.5% |

Siv Jensen |

| 2011 | 11.8% |

11.4% |

Siv Jensen |

| 2015 | 10,2% |

9,5% |

Siv Jensen |

See also

References

- ↑ "Færre betalende Frp-medlemmer i 2014". Dagens Næringsliv. 22 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Norway – Political parties". Norwegian Social Science Data Services. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- 1 2 Wolfram Nordsieck (2013). "Parties and Elections in Europe: Norway". www.parties-and-elections.eu. Parties and Elections in Europe.

- ↑ Herbert Kitschelt (1997). The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. University of Michigan Press. pp. 154-155.

- 1 2 Jens Rydgren (2013). Class Politics and the Radical Right. Routledge. p. 108.

- ↑ Widfeldt 2014, p. 94-95.

- 1 2 3 "Frp sier nei til EU for første gang". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). NTB. 4 September 2016.

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2015/jun/19/rightwing-anti-immigration-parties-nordic-countries-denmark-sweden-finland-norway

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/burkini-ban-norway-france-progress-party-right-wing-islam-swimwear-muslims-a7211271.html

- ↑ http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-norway-election-idUKKCN0RE25620150914

- ↑ "Valg 2011: Landsoversikt per parti" (in Norwegian). Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ↑ "Framstegspartiet". Valg 2011 (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20140317021549/http://www.valgresultat.no/bz5.html. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Information in English". frp.no. 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "Fremskrittspartiet / The Progress Party – Reminder – Press Conference: The Progress Party – International Reactions and Relations", Reuters, Sep 15, 2013

- ↑ Allern 2010, p. 26: "The Norwegian Progress Party is...traditionally characterised as a borderline case of the extreme or radical right (Ignazi 1992: 13–15; Kitschelt 1995: 121; Ignazi 2003: 157), and Mudde (2007:19) characterises FrP as a non-radical populist party"; see also: p.212.

- ↑ Widfeldt 2014, p. 83: "The academic literature is not unanimous in classifying FrP as an extreme right party. Cas Mudde, in his book from 2007, argues that FrP does not belong to the populist radical right family... Instead, he classifies FrP as a "neoliberal populist party". Other writers, however, do place FrP in the same category...even if they in some cases do so with qualifications"; see also: p.16.

- ↑ "Forskere: Frp er høyrepopulistisk", Verdens Gang (NTB), 14.09.2013. "- Ja, de er høyrepopulister. Men sammenlignet med andre slike partier i Europa er de en moderat utgave og har sterkere innslag av liberalkonservative strømninger, sier Jupskås." ("Yes, they are right-wing populists. But compared to similar parties in Europe, they are a moderate version, and have stronger elements of liberal-conservative currents, Jupskås (Anders Ravik Jupskås, lecturer Department of Political Science, University of Oslo) says.")

- ↑ "New Norway PM defends right-wing partner", The Local, 13 Sep 2013

- ↑ "KrF og Venstre forsvarer Frp" [KrF and Venstre defend Frp], NRK, 12.09.2013

- ↑ "Progress calls press to protest Breivik link", The Local, 16 Sep 2013: "[Frank Aarebrot, professor of comparative politics at Bergen University], who is a member of the Labour Party, told Aftenposten. "It is unreasonable to compare the Progress Party with the Danish People's Party, the Sweden Democrats and the True Finns," he added."

- ↑ "Economist's Jensen - le Pen comparison 'crude'". The Local (no). 3 January 2014.

Knut Heidar, politics professor at the University of Oslo, said that the comparison with the National Front and other European parties was problematic: “It’s a result of crude categorisation. You put them all in the same bag and think they’re all alike. But the Progress Party is more moderate on nearly all points. This is why it’s not as controversial in Norway as it is in foreign media.” [...] “They’re really more like the Norwegian or British Conservative parties than they are like the Austrian Freedom Party, the Vlaams Bloc or the National Front,” he added.

- ↑ "For Norwegians, Progress Party not far-right", Deutsche Welle, 11.11.2013

- 1 2 "Norway election: Erna Solberg to form new government" BBC News Sept. 9, 2013

- 1 2 Overland, Jan-Arve; Tønnessen, Ragnhild. "Hva står de politiske partiene for?" [What do the political parties stand for?]. Nasjonal Digital Læringsarena (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Widfeldt 2014, p. 109, 113.

- 1 2 3 Forr, Gudleiv. "Carl I Hagen". In Helle, Knut. Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- 1 2 "Populists left out of new Norway government", The Local, 16 Oct 2013

- ↑ Wayne C. Thompson (2014). Nordic, Central, and Southeastern Europe 2014. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 55.

- ↑ "Kenya's Westgate attack: Norway's Progress party faces its first test", The Guardian, 18 October 2013

- 1 2 3 4 5 Meland, Astrid (8 April 2003). "I kinosalens mørke" [In the darkness of the movie theater]. Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- 1 2 "Ideology and Principles of the Progress Party" (PDF). FrP.no. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ Stanghelle, Harald (6 September 2010). "De oversettes opprør" [The rebellion of the neglected]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ↑ "Andre toner på Youngstorget" [Different tones at Youngstorget]. Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). 16 May 1973. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Arter 1999, p. 105.

- ↑ "Anders Lange's speech at Saga Kino, 8 April 1973" (in Norwegian). Virksomme Ord. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ Jungar & Jupskås 2010, p. 5.

- ↑ Sandnes, Børge (30 April 2003). "Fremskrittspartets historie" [History of the Progress Party] (in Norwegian). Svelvik FrP. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 Løset, Kjetil (15 June 2009). "FrPs historie" [History of the Frp] (in Norwegian). TV2. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tvedt, Knut Are (29 September 2009). "Fremskrittspartiet – Frp" [The Progress Party – Frp]. Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ Arter 1999, p. 106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Fremskritt fra dag en" [Progress from day one]. Dagbladet Magasinet (in Norwegian). 5 March 2001. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- 1 2 Magnus, Gunnar (4 May 2006). "Fra parentes til mektig partieier" [From parenthesis to powerful party owner]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Simonsen 2007, p. 40.

- ↑ Danielsen, Per (2 May 1983). "Ønsker samarbeide med Høyre på sikt: Liberalismen Fr.p.s nye ideologi". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 5. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

Fremskrittspartiet ønsker et samarbeide med Høyre. Liberalismen er blitt partiets ideologi. Dette er to sentrale hovedkonklusjoner fra partiets landsmøte i Sandefjord, som blr [sic] avsluttet søndag.

- 1 2 Martinsen, Vegard (May 2003). "EU og globalisering Fredsbevegelsen Velferdsstatens moralske tåkeslott Liberalismens historie i Norge, del 2" [The EU and globalisation The peace movement The moral castle in the clouds of the welfare state The history of Liberalism in Norway, part 2] (PDF). Tidsskriftet Liberal for individuell frihet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ↑ "Ruling coalition takes narrow win over left in Norwegian election". The Montreal Gazette. 10 September 1985. p. 58. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Skjørestad 2008, p. 40.

- ↑ Hagelund 2005, p. 152.

- 1 2 Hagelund 2005, p. 155.

- 1 2 Salvesen, Geir (27 September 1988). "Hagen: Folket må selv bestemme innvandring" [Hagen: The people must make the decions on immigration themselves]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ↑ "Får trolig flere ordførere" [Will probably have several mayors]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 11 September 2007. p. 9. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ↑ "Rege tar gjenvalg" [Rege stands for re-election]. Stavanger Aftenblad (in Norwegian). www.aftenbladet.no. 16 August 2006. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Jubilanter: 70 år" [Anniversaries: 70 years]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 11 September 2007. p. 16. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ↑ "Tidligere ordførere" [Previous mayors]. Oslo municipality (in Norwegian). www.ordforeren.oslo.kommune.no. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ Olaussen, Lise Merete. "Siv Jensen". In Helle, Knut. Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Simonsen 2007, p. 5.

- ↑ "Det nye landet: Kampen", 26 January 2010. Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (television).

- ↑ "Gratulerer FpU" [Congratulates the Youth of the Progress Party] (in Norwegian). Progress Party's Youth. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Vestre, Trond (17 August 2009). "EU-debatten – en kjepp i hjulet" [The EU debate – a spanner in the works] (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Simonsen 2007, p. 42.

- ↑ "Kort om partiets historie" [Briefly on the party's history] (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- 1 2 Skjørestad 2008, p. 9.

- ↑ Skjørestad 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ "Fremskrittspartiets historie: Valgåret 1995" [The history of the Progress Party: The election year 1995] (in Norwegian). Frp.no. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Elvik, Halvor (3 September 1999). "Pitbullene er løs!" [The pitbullsa re lose!]. Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Bleness, Carsten (8 September 1995). "Velgerstrøm til Fr.p.". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 4. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- 1 2 Simonsen, Jan (10 September 2009). "Mitt forhold til Fremskrittspartiet" [My relations with the Progress Party] (in Norwegian). Frie Ytringer, Jan Simonsen's blog. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Fremskrittspartiets historie: Valget 2001 og ny turbulens i partiet" [History of the Progress Party: The 2001 election and new turbulence in the party] (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- 1 2 Vinding, Anne (31 October 2007). "- Jeg har vært kravstor og maktsyk: Slik kvittet Carl I Hagen seg med "syverbanden" i Frp" [- I have been demanding and power hungry: How Carl I Hagen rid himself of the "Gang of Seven" in the Frp]. Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Avkrefter påstander om kupp" [Denies coup allegations]. Smaalenenes Avis (in Norwegian). 23 January 2001. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ↑ Magnus, Gunnar (23 January 2001). "Hagen frykter kupp i partiet". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ↑ Melbye, Olav (30 August 2009). "Superreserven Carl I. Hagen" [Carl I. Hagen, the super-sub]. Drammens Tidende (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Høstmælingen, Siri Haave (28 February 2001). "Haoko Tveitt melder seg ut av Frp" [Haoko Tveitt leaves the Frp]. Bergensavisen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Frp'ere melder seg ut" [Frp members leave the party] (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 March 2001. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Kleppe suspendert" [Kleppe suspended]. Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). www.vg.no. 7 March 2001. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Skjørestad 2007, p. 5.

- ↑ Vinding, Anne; Ryste, Camilla (31 October 2007). "Hedstrøm til angrep på Hagen" [Hedstrøm attacks Hagen]. Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Simonsen 2007, p. 44.

- ↑ "Norway far-right sets new course". BBC Online. 16 October 2001. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Braanen, Bjørgulv (2 May 2002). "Høyre taper til Frp" [Conservative Party loses to the Frp]. Klassekampen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Løkeland-Stai, Espen; Marsdal, Magnus (30 April 2002). "Trussel mot demokratiet" [A threat to democracy]. Klassekampen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Hagelund 2005, p. 148.

- ↑ "Fremskrittspartiets historie: Konsolidering og kommunevalg" [History of the Progress Party: Consolidation and municipal elections] (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ↑ Notaker, Hallvard (16 September 2003). "Frp størst i 36 kommuner" [Frp largest in 36 municipalities] (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Close result expected as Norwegians head to polls". The New York Times. 11 September 2005. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ↑ "Norwegian PM announces resignation". The Guardian. 13 September 2005. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ↑ "FrP og Høyre går kraftig fram" [Strong advances for the Frp and the Conservative Party] (in Norwegian). TNS Gallup. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ Magerøy, Lars Halvor; Haugan, Bjørn (31 May 2008). "Fosser frem på diesel-opprør: Siv nær statsministerstolen" [Surges ahead because of diesel rebellion: Siv close to the prime minister's chair]. Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ "Frp størst på ny måling". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). 4 June 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ "Frp over 30 prosent på ny måling (NTB)". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). 26 June 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- 1 2 "Fremskrittspartiets historie: 2007 Eksamen for ordførere" (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ↑ Elster, Kristian (11 September 2009). "Brakvalg for Frp-ordførere" [Good election for FrP majors]. Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (in Norwegian). www.nrk.no. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Partibarometeret" (in Norwegian). TV2. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Gibbs, Walter (15 September 2009). "Norway Keeps Leftists in Power". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Buch-Andersen, Thomas (20 April 2009). "Islam a political target in Norway". BBC News. Oslo: news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ↑ "FrP og framgangen (4:47 min)" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ Pulk, Åse (15 September 2009). "– Vi har gjort et brakvalg" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Skolevalg 2009" (in Norwegian). NSD Samfunnsveven. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Rent flertall for Høyre og Frp i april". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). 3 May 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Blåblått flertall i juni". Dagens Næringsliv (in Norwegian). 29 June 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Partibarometeret". TV 2 (in Norwegian). Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ "Ap mindre enn både Høyre og Frp". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). 23 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ↑ Aune, Oddvin (12 September 2011). "Frp mot sitt dårligste valg på 16 år" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ↑ Klungtveit, Harald S. (13 September 2011). "- Utøya-effekten ble at Frp-velgerne satt i sofaen". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ↑ Bjørgan, Linda (7 September 2009). "Rungende nei til Frp" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Joswig, Rebekka (28 April 2009). "Nei til Frp-samarbeid". Vårt Land (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Horn, Anders (24 April 2008). "Ernas umulige prosjekt". Klassekampen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Ingen ny regjering uten Frp". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 15 July 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Sand, Lars Nehru (12 July 2006). "Stiller Frp-ultimatum". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Meisingset, Sigrun Lossius; Ertzeid, Heidi (3 October 2007). "RV og SV inngår allianse med Frp". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sjøli, Hans Petter (25 September 2008). "Sier nei til Kjærsgaard". Klassekampen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ↑ Widfeldt 2014, p. 95-96.

- 1 2 "Fremskrittspartiets prinsipper 2009–2013" (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ↑ Skjørestad 2008, p. 7.

- ↑ Ørjasæter, Elin (27 July 2009). "Splittet Fremskrittsparti" (in Norwegian). E24 Næringsliv. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Thorenfeldt, Gunnar (7 May 2009). "Norges nye jernlady". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Skjørestad 2008, p. 85.

- ↑ Skjørestad 2008, p. 8.

- ↑ Skjørestad 2008, p. 11.

- ↑ Jensen, Siv (26 October 2006). "Hva FrP ikke er". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- 1 2 "Økonomisk politikk" [Economic policy]. Frp.no (in Norwegian). Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ↑ DeShayes, Pierre-Henry (14 September 2009). "Norway votes in close general election". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Vi mener: Skole- og utdanningspolitikk" (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ↑ "Vi mener: Familiepolitikk" (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ↑ "Same-sex marriage and civil unions in Norway". Religioustolerance.org. 1993-04-30. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ↑ Norway adopts gender neutral marriage law ilga-europe.org

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20110520153827/http://afp.google.com/article/ALeqM5jko_BIHizUFFqUtmEaUrAEoPXFWw. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20080617115242/http://www.aftenposten.no/english/local/article2479146.ece. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Frp snur i homo-spørsmål - NRK Norge - Oversikt over nyheter fra ulike deler av landet". Nrk.no. 2012-10-16. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ↑ Lars Joakim Skarvøy (2012-10-16). "Slik skal Frp-Siv flørte med homo-velgerne - Foreldre og barn - VG". Vg.no. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ↑ "Frp vil la homofile gifte seg og adoptere barn - Aftenposten". Aftenposten.no. 2014-01-31. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ↑ http://www.frp.no/Gi+homofile+mulighet+til+%C3%A5+gi+blod.d25-TMZHIX8.ips. Retrieved 26 May 2013. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Tristan Dupré (2012-07-30). "– La homofile gi blod! | Fremskrittspartiets Ungdom". Fpu.no. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ↑ "Vi mener: Kulturpolitikk" (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ↑ "Fremskrittspartiets samepolitikk" [Progress Party's sami politics] (PDF). Fremskrittspartiets stortingsgruppe. Stortingsgruppens politiske faktaark (in Norwegian): 3. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

FrP vil: Nedlegge Sametinget som politisk organ og gjenopprette samerådet som rådgivende organ til Stortinget. Frem til dette skjer vil FrP arbeide for at Sametinget skal være et ikke-etnisk betinget organ.

- ↑ "Vi mener: Samepolitikk" (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ↑ Mjelde 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ Torvik, Line (25 May 2006). "Ap-Kolberg: Har knekket Frp-koden" [Ap-Kolberg: Has solved the Frp-code]. Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). www.vg.no. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Simonsen 2007.

- 1 2 3 Hagelund 2005, p. 147.

- ↑ Skjørestad 2008.

- ↑ Lågbu, Øivind (24 June 2008). "Ap tilpasser seg Frp". Fredriksstad Blad (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- 1 2 Gran, Even (12 February 2003). "Populisme – et sunnhetstrekk". Forskning.no (in Norwegian). Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ↑ "Vi mener: Justispolitikk" (PDF) (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- 1 2 Hagelund 2005, p. 149.

- ↑ Simonsen 2007, p. 15.

- ↑ Skjørestad 2008, p. 15.

- ↑ Olsen, Per Arne; Norheim, Kristian (7 September 2009). "Fremskrittspartiet knappast en förebild för Sverigedemokraterna". Sveriges Television (in Swedish). Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- 1 2 "Vi mener: Asyl- og innvandringspolitikk" (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Magnus, Gunnar (12 August 2007). "Jensen vil beholde lovlydige utlendinger". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ↑ "Vil redusere asylstrømmen med 90 prosent". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). 17 July 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 Rønneberg, Kristoffer (7 April 2008). "Frp vil stenge grensen". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ Skevik, Erlend (9 June 2010). "Frp: – Fullt mulig å stanse innvandringen". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Lepperød, Trond (15 June 2010). "En av fem vil være innvandrer". Nettavisen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- 1 2 Castello, Claudio (1 September 2009). "Flere innvandrere stemmer FrP". Utrop (in Norwegian). Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ Akerhaug, Lars (1 September 2009). "- Innvandrere stemmer Frp – som folk flest". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Thorenfeldt, Gunnar (9 March 2009). "Snikislamiserer Frp". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Salvesen, Geir (24 May 2009). "Hva gjør disse i Fremskrittspartiet?". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Vi mener: EU, EØS og Schengen" (in Norwegian). Frp.no. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ↑ Akerhaug, Lars (23 July 2009). "Siv: – EU-saken er en ikke-sak". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Vi mener: Utenrikspolitikk" (in Norwegian). Frp.no. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- 1 2 "Vi beklager...". Frp.no. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ↑ Hanssen, Lars Joakim (9 January 2009). "FrPs syn på konflikten i Midtøsten" (in Norwegian). Frp.no. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Sæle, Finn Jarle (29 June 2010). "Den nye høyrebølgen". Norge Idag (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Larsen, Christiane Jordheim (6 January 2009). "Full tillit til Israel i Frp". Klassekampen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Jensen vil flytte norsk ambassade til Jerusalem". Verdens Gang (NTB) (in Norwegian). 27 August 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ↑ "- Hvorfor bør jeg velge Frp i stedet for Høyre?". Stavanger Aftenblad (in Norwegian). 5 February 2010. Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ↑ "Vi mener: Utviklingspolitikk" (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Olsen, Maren Næss; Dahl, Miriam S. (16 January 2009). "Populister på partnerjakt" (PDF). Ny Tid (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Natland, Jarle (5 May 2008). "Frp skal bygge sitt eget internasjonale omdømme". Stavanger Aftenblad (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Lepperød, Trond (10 September 2009). "Slik er asylpolitikken Frp vil kopiere". Nettavisen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Berg, Morten Michelsen (17 April 2009). "Venstre i Danmark omfavner Frp" (in Norwegian). TV2. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ↑ "Støjberg kritiseres for norsk tale". Jyllands-Posten (in Danish). 7 April 2009. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Kirkebække, Heidi; Buch-Andersen, Thomas (17 April 2009). "Støjberg-støtte til Fremskrittspartiet skaber røre" (in Danish). Danmarks Radio. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- 1 2 Mathisen, Anita Vikan; Karlsen, Terje (11 September 2009). "Følger Frp med argusøyne". Ny Tid (in Norwegian). Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ↑ Larsen, Tore Andreas (15 November 2007). "- Tøvete sammenligning" (in Norwegian). Frp.no. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Simonsen, Jan (23 September 2013). "Godt, men ikke godt nok, for tyske EU-skeptikere i "Alternativ for Tyskland"" (in Norwegian). Frie Ytringer, Jan Simonsens Blogg. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ Mollatt, Camilla (8 May 2009). "Siv Jensen holder foredrag for ledere i britisk politikk og næringsliv" (in Norwegian). FrP.no. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Republican Party Chairman greets the Progress Party". FrP.no. 18 May 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Gjerstad, Tore (5 January 2008). "Stortinget vil ha Hillary Clinton". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Knuser Obama". Fremskritt (in Norwegian) (16): 8. 25 October 2008.

John McCain er FrP-favoritt til å USAs neste president. 14 av 19 spurte fylkesformenn ville stemt på republikanerne.

- ↑ Magnus, Gunnar (24 April 2010). "Tea Party-misjonær tente Frps landsmøte". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Lepperød, Trond (24 April 2010). "Her henter Frp inspirasjon". Nettavisen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Lørdagsrevyen" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. 28 August 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

Bibliography

- Allern, Elin Haugsgjerd (2010). Political Parties and Interest Groups in Norway. ECPR Press. ISBN 9780955820366.

- Arter, David (1999). Scandinavian politics today. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5133-9.

- Gingrich, André; Banks, Marcus (2006). Neo-nationalism in Europe and beyond: perspectives from social anthropology. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-84545-190-2.

- Hagelund, Anniken (2005). Rydgren, Jens, ed. Movements of exclusion: radical right-wing populism in the Western world. Nova. ISBN 1-59454-096-9

- Jungar, Ann-Cathrine; Jupskås, Anders Ravik (2010). En Populistisk Partifamilie?: En Komparativ-Historisk Analyse Av Nordiske Populistpartier. Högerpopulistiska partier och främlingsfientlig opinion i Europa: Framgång och inflytande (essay). University of Gothenburg.

- Mjelde, Hilmar Langhelle (2008). Explaining Membership Growth in the Norwegian Progress Party from 1973 to 2008. University of Bergen. hdl:1956/3080.

- Simonsen, Tor Espen (2007). Høyrepopulismens politiske metamorfose på 1990-tallet. En komparativ studie av tre nordiske partier: Fremskridtspartiet, Dansk Folkeparti og Fremskrittspartiet. (thesis) (in Norwegian). CULCOM.

- Skjørestad, Anna (2008). Et liberalistisk parti? Fremskrittspartiets politiske profil fra 1989 til 2005 (thesis) (in Norwegian). University of Bergen. hdl:1956/2927.

- Widfeldt, Anders (2014). Extreme Right in Scandinavia. Routledge. ISBN 9781134502158.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Progress Party. |

- (Norwegian) Progress Party (FrP) – official site

- Progress Party (FrP) – official site in English

- (Norwegian) Official programme, in Norwegian

- (Norwegian) Youth of the Progress Party (FpU) – official site