Retrovirus

| Retroviruses | |

|---|---|

| |

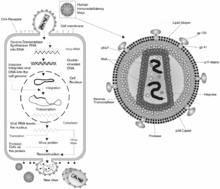

| HIV retrovirus schematic of cell infection, virus production and virus structure | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group VI (ssRNA-RT) |

| Order: | Unassigned |

| Family: | Retroviridae |

| Genera | |

|

Subfamily: Orthoretrovirinae Subfamily: Spumaretrovirinae | |

A retrovirus is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus with a DNA intermediate and, as an obligate parasite, targets a host cell. Once inside the host cell cytoplasm, the virus uses its own reverse transcriptase enzyme to produce DNA from its RNA genome, the reverse of the usual pattern, thus retro (backwards). The new DNA is then incorporated into the host cell genome by an integrase enzyme, at which point the retroviral DNA is referred to as a provirus. The host cell then treats the viral DNA as part of its own genome, translating and transcribing the viral genes along with the cell's own genes, producing the proteins required to assemble new copies of the virus. It is difficult to detect the virus until it has infected the host. At that point, the infection will persist indefinitely.

In most viruses, DNA is transcribed into RNA, and then RNA is translated into protein. However, retroviruses function differently, as their RNA is reverse-transcribed into DNA, which is integrated into the host cell's genome (when it becomes a provirus), and then undergoes the usual transcription and translational processes to express the genes carried by the virus.The information contained in a retroviral gene is thus used to generate the corresponding protein via the sequence: RNA → DNA → RNA → polypeptide. This extends the fundamental process identified by Francis Crick (one gene-one peptide) in which the sequence is DNA → RNA → peptide (proteins are made of one or more polypeptide chains; for example, haemoglobin is a four-chain peptide).

Retroviruses are valuable research tools in molecular biology, and they have been used successfully in gene delivery systems.[1]

Structure

Virions of retroviruses consist of enveloped particles about 100 nm in diameter. The virions also contain two identical single-stranded RNA molecules 7–10 kilobases in length. Although virions of different retroviruses do not have the same morphology or biology, all the virion components are very similar.[2]

The main virion components are:

- Envelope: composed of lipids (obtained from the host plasma membrane during budding process) as well as glycoprotein encoded by the env gene. The retroviral envelope serves three distinct functions: protection from the extracellular environment via the lipid bilayer, enabling the retrovirus to enter/exit host cells through endosomal membrane trafficking, and the ability to directly enter cells by fusing with their membranes.

- RNA: consists of a dimer RNA. It has a cap at the 5' end and a poly(A) tail at the 3' end. The RNA genome also has terminal noncoding regions, which are important in replication, and internal regions that encode virion proteins for gene expression. The 5' end includes four regions, which are R, U5, PBS, and L. The R region is a short repeated sequence at each end of the genome used during the reverse transcription to ensure correct end-to-end transfer in the growing chain. U5, on the other hand, is a short unique sequence between R and PBS. PBS (primer binding site) consists of 18 bases complementary to 3' end of tRNA primer. L region is an untranslated leader region that gives the signal for packaging of the genome RNA. The 3' end includes 3 regions, which are PPT (polypurine tract), U3, and R. The PPT is a primer for plus-strand DNA synthesis during reverse transcription. U3 is a sequence between PPT and R, which serves as a signal that the provirus can use in transcription. R is the terminal repeated sequence at 3' end.

- Proteins: consisting of gag proteins, protease (PR), pol proteins, and env proteins.

- Group-specific antigen (gag) proteins are major components of the viral capsid, which are about 2000–4000 copies per virion.

- Protease is expressed differently in different viruses. It functions in proteolytic cleavages during virion maturation to make mature gag and pol proteins.

- Pol proteins are responsible for synthesis of viral DNA and integration into host DNA after infection.

- Env proteins play a role in association and entry of virions into the host cell.[3] Possessing a functional copy of an env gene is what makes retroviruses distinct from retroelements.[4] The ability of the retrovirus to bind to its target host cell using specific cell-surface receptors is given by the surface component (SU) of the Env protein, while the ability of the retrovirus to enter the cell via membrane fusion is imparted by the membrane-anchored trans-membrane component (TM). Thus it is the Env protein that enables the retrovirus to be infectious.

Multiplication

When retroviruses have integrated their own genome into the germ line, their genome is passed on to a following generation. These endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), contrasted with exogenous ones, now make up 5-8% of the human genome.[5] Most insertions have no known function and are often referred to as "junk DNA". However, many endogenous retroviruses play important roles in host biology, such as control of gene transcription, cell fusion during placental development in the course of the germination of an embryo, and resistance to exogenous retroviral infection. Endogenous retroviruses have also received special attention in the research of immunology-related pathologies, such as autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis, although endogenous retroviruses have not yet been proven to play any causal role in this class of disease.[6]

While transcription was classically thought to occur only from DNA to RNA, reverse transcriptase transcribes RNA into DNA. The term "retro" in retrovirus refers to this reversal (making DNA from RNA) of the central dogma of molecular biology. Reverse transcriptase activity outside of retroviruses has been found in almost all eukaryotes, enabling the generation and insertion of new copies of retrotransposons into the host genome. These inserts are transcribed by enzymes of the host into new RNA molecules that enter the cytosol. Next, some of these RNA molecules are translated into viral proteins. For example, the gag gene is translated into molecules of the capsid protein, the pol gene is translated into molecules of reverse transcriptase, and the env gene is translated into molecules of the envelope protein. It is important to note that a retrovirus must "bring" its own reverse transcriptase in its capsid, otherwise it is unable to utilize the enzymes of the infected cell to carry out the task, due to the unusual nature of producing DNA from RNA.

Industrial drugs that are designed as protease and reverse transcriptase inhibitors are made such that they target specific sites and sequences within their respective enzymes. However these drugs can quickly become ineffective due to the fact that the gene sequences that code for the protease and the reverse transcriptase quickly mutate. These changes in bases cause specific codons and sites with the enzymes to change and thereby avoid drug targeting by losing the sites that the drug actually targets.

Because reverse transcription lacks the usual proofreading of DNA replication, a retrovirus mutates very often. This enables the virus to grow resistant to antiviral pharmaceuticals quickly, and impedes the development of effective vaccines and inhibitors for the retrovirus.[7]

One difficulty faced with some retroviruses, such as the Moloney retrovirus, involves the requirement for cells to be actively dividing for transduction. As a result, cells such as neurons are very resistant to infection and transduction by retroviruses. This gives rise to a concern that insertional mutagenesis due to integration into the host genome might lead to cancer or leukemia. This is unlike Lentivirus, a genus of Retroviridae, which are able to integrate their RNA into the genome of non-dividing host cells.

Transmission

- Cell-to-cell[8]

- Fluids

- Airborne, like the Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus.

Provirus

This DNA can be incorporated into host genome as a provirus that can be passed on to progeny cells. The retrovirus DNA is inserted at random into the host genome. Because of this, it can be inserted into oncogenes. In this way some retroviruses can convert normal cells into cancer cells. Some provirus remains latent in the cell for a long period of time before it is activated by the change in cell environment.

Early evolution

Studies of retroviruses led to the first demonstrated synthesis of DNA from RNA templates, a fundamental mode for transferring genetic material that occurs in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. It has been speculated that the RNA to DNA transcription processes used by retroviruses may have first caused DNA to be used as genetic material. In this model, the RNA world hypothesis, cellular organisms adopted the more chemically stable DNA when retroviruses evolved to create DNA from the RNA templates.

Gene therapy

Gammaretroviral and lentiviral vectors for gene therapy have been developed that mediate stable genetic modification of treated cells by chromosomal integration of the transferred vector genomes. This technology is of use, not only for research purposes, but also for clinical gene therapy aiming at the long-term correction of genetic defects, e.g., in stem and progenitor cells. Retroviral vector particles with tropism for various target cells have been designed. Gammaretroviral and lentiviral vectors have so far been used in more than 300 clinical trials, addressing treatment options for various diseases.[1][9] Retroviral mutations can be developed to make transgenic mouse models to study various cancers and their metastatic models.

Cancer

Retroviruses that cause tumor growth include Rous sarcoma virus and Mouse mammary tumor virus. Cancer can be triggered by proto-oncogenes that were mistakenly incorporated into proviral DNA or by the disruption of cellular proto-oncogenes. Rous sarcoma virus contains the src gene that triggers tumor formation. Later it was found that a similar gene in cells is involved in cell signaling, which was most likely excised with the proviral DNA. Nontransforming viruses can randomly insert their DNA into proto-oncogenes, disrupting the expression of proteins that regulate the cell cycle. The promoter of the provirus DNA can also cause over expression of regulatory genes.

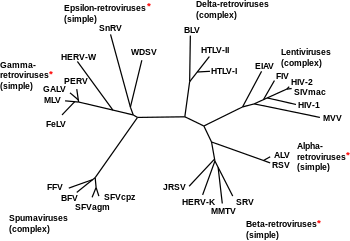

Classification

Exogenous

These are infectious RNA-containing viruses which are transmitted from human to human.

The following genera are included here:

- Genus Alpharetrovirus; type species: Avian leukosis virus; others include Rous sarcoma virus

- Genus Betaretrovirus; type species: Mouse mammary tumour virus

- Genus Gammaretrovirus; type species: Murine leukemia virus; others include Feline leukemia virus

- Genus Deltaretrovirus; type species: Bovine leukemia virus; others include the cancer-causing Human T-lymphotropic virus

- Genus Epsilonretrovirus; type species: Walleye dermal sarcoma virus

- Genus Lentivirus; type species: Human immunodeficiency virus 1; others include Simian, Feline immunodeficiency viruses

- Genus Spumavirus; type species: Simian foamy virus

These were previously divided into three subfamilies (Oncovirinae, Lentivirinae, and Spumavirinae), but are now divided into two: Orthoretrovirinae and Spumaretrovirinae. The term oncovirus is now commonly used to describe a cancer-causing virus.

Retroviruses were in 2 groups of the Baltimore classification.

Group VI viruses

All members of Group VI use virally encoded reverse transcriptase, an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase, to produce DNA from the initial virion RNA genome. This DNA is often integrated into the host genome, as in the case of retroviruses and pseudoviruses, where it is replicated and transcribed by the host.

Group VI includes:

- Family Metaviridae

- Family Pseudoviridae

- Family Retroviridae — Retroviruses, e.g. HIV

Group VII viruses

Both families in Group VII have DNA genomes contained within the invading virus particles. The DNA genome is transcribed into both mRNA, for use as a transcript in protein synthesis, and pre-genomic RNA, for use as the template during genome replication. Virally encoded reverse transcriptase uses the pre-genomic RNA as a template for the creation of genomic DNA.

Group VII includes:

- Family Hepadnaviridae — e.g. Hepatitis B virus

- Family Caulimoviridae — e.g. Cauliflower mosaic virus

Endogenous

Endogenous retroviruses are not formally included in this classification system, and are broadly classified into three classes, on the basis of relatedness to exogenous genera:

- Class I are most similar to the gammaretroviruses

- Class II are most similar to the betaretroviruses and alpharetroviruses

- Class III are most similar to the spumaviruses.

Treatment

Antiretroviral drugs are medications for the treatment of infection by retroviruses, primarily HIV. Different classes of antiretroviral drugs act on different stages of the HIV life cycle. Combination of several (typically three or four) antiretroviral drugs is known as highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART).[10]

Treatment of veterinary retroviruses

Feline leukemia virus and Feline immunodeficiency virus infections are treated with biologics, including the only immunomodulator currently licensed for sale in the United States, Lymphocyte T-Cell Immune Modulator (LTCI).[11]

References

- 1 2 Kurth, Reinhard; Bannert, Norbert, eds. (2010). Retroviruses: Molecular Biology, Genomics and Pathogenesis. Horizon Scientific. ISBN 978-1-904455-55-4.

- ↑ Coffin, John M. (1992). "Structure and Classification of Retroviruses". In Levy, Jay A. The Retroviridae. 1 (1st ed.). New York: Plenum. p. 20. ISBN 0-306-44074-1.

- ↑ Coffin 1992, pp. 26–34

- ↑ Kim FJ, Battini JL, Manel N, Sitbon M (January 2004). "Emergence of vertebrate retroviruses and envelope capture". Virology. 318 (1): 183–91. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2003.09.026. PMID 14972546.

- ↑ Robert Belshaw; Pereira V; Katzourakis A; Talbot G; Paces J; Burt A; Tristem M. (April 2004). "Long-term reinfection of the human genome by endogenous retroviruses". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101 (14): 4894–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0307800101. PMC 387345

. PMID 15044706.

. PMID 15044706. - ↑ Medstrand P, van de Lagemaat L, Dunn C, Landry J, Svenback D, Mager D (2005). "Impact of transposable elements on the evolution of mammalian gene regulation". Cytogenet Genome Res. 110 (1-4): 342–52. doi:10.1159/000084966. PMID 16093686.

- ↑ Svarovskaia ES; Cheslock SR; Zhang WH; Hu WS; Pathak VK. (January 2003). "Retroviral mutation rates and reverse transcriptase fidelity.". Front Biosci. 8 (1-3): d117–34. doi:10.2741/957. PMID 12456349.

- ↑ Jolly C (March 2011). "Cell-to-cell transmission of retroviruses: Innate immunity and interferon-induced restriction factors.". Virology. 411 (2): 251–9. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.031. PMC 3053447

. PMID 21247613.

. PMID 21247613. - ↑ Desport, M, ed. (2010). Lentiviruses and Macrophages: Molecular and Cellular Interactions. Caister Academic. ISBN 978-1-904455-60-8.

- ↑ Haddad M, Inch C, Glazier RH, et al. (2000). "Patient support and education for promoting adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001442. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001442. PMID 10908497.

- ↑ Gingerich DA (2008). "Lymphocyte T-cell immunomodulator (LTCI): Review of the immunopharmacology of a new biologic" (PDF). Intern J Appl Res Vet Med. 6 (2): 61–8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Retroviruses. |

- ViralZone A Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics resource for all viral families, providing general molecular and epidemiological information (follow links for "Retro-transcribing viruses")

- Retrovirus Animation (Flash Required)

- Retrovirology Scientific journal

- Retrovirus life cycle chapter From Kimball's Biology (online biology textbook pages)

- Coffin, John M; Hughes, Stephen H; Varmus, Harold E, eds. (1997). Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. ISBN 0-87969-571-4. NBK19376.

- Specter, Michael (3 December 2007). "Annals of Science: Darwin's Surprise". The New Yorker.