Sino-Soviet border conflict

| Sino-Soviet border conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and the Sino-Soviet split | |||||||||

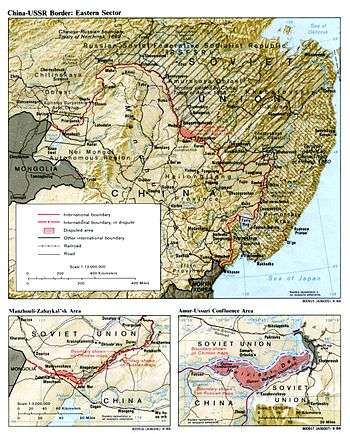

Some of the disputed areas in the Argun and Amur rivers. Damansky/Zhenbao is to the southeast, north of the lake | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 658,000 | 814,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

59 killed 94 wounded (Soviet sources)[3] 27 Tanks/APCs destroyed (Chinese sources)[4] 1 Command Car (Chinese sources)[5] Dozens of trucks destroyed (Chinese sources)[6] One Soviet T-62 tank captured[1] |

71 killed and 68 wounded (Chinese sources) ~800 killed[7] (Soviet sources)[8] | ||||||||

The Sino-Soviet border conflict was a seven-month undeclared military conflict between the Soviet Union and China at the height of the Sino-Soviet split in 1969. Although military clashes ceased that year, the underlying issues were not resolved until the 1991 Sino-Soviet Border Agreement.

The most serious of these border clashes—which brought the two communist-led countries to the brink of war—occurred in March 1969 in the vicinity of Zhenbao (Damansky) Island on the Ussuri (Wusuli) River; as such, Chinese historians most commonly refer to the conflict as the Zhenbao Island Incident.[9]

Background

History

Under the governorship of Sheng Shicai (1933–1944) in northwest China's Xinjiang (then Sinkiang) province, China's nationalist Kuomintang recognized for the first time the existence of a "Uyghur people", following Soviet ethnic policy. This ethnogenesis of a "national" people eligible for territorialized autonomy broadly benefited the Soviet Union, which organized conferences in Fergana and Semirechye (in Soviet Central Asia), in order to cause "revolution" in Altishahr (southern Xinjiang) and Dzungaria (northern Xinjiang).[10] Both the Soviet Union and the White movement covertly armed and fought with the Ili National Army which fought against the Kuomintang in the Three Districts Revolution. Although the mostly Muslim Uyghur rebels participated in pogroms against Han Chinese in general, the turmoil eventually just resulted in the replacement of Kuomintang rule in Xinjiang (northwest China) with that of the Communist Party of China in the 1940s.[11]

On the academic side, Soviet historiography and more specifically Soviet "Uyghur Studies" were politicized in increasing measure to match the tenor of the Sino-Soviet split from the 1960s and 1970s. One Soviet Turkologist named Tursun Rakhminov, who worked for the CPSU, argued that it was the modern Uyghurs who founded the ancient Toquz Oghuz Country (744-840), the Kara-Khanid Khanate (840–1212), and so forth. These premodern states' wars against Chinese dynasties were cast as struggles for national liberation by the Uyghur ethnic group. Soviet historiography was not consistent on these questions: when Sino-Soviet relations were warmer, for example, the Three Districts Revolution was portrayed by Soviet historians as part of the greater Chinese anti-Kuomintang revolution, and not an anti-Chinese bid for national liberation. The Soviet Union also encouraged migration of Uyghurs to its territory in Kazakhstan along the 4,380 km (2,738 mi) border. In May, 1962, when 60,000 ethnic Uyghurs in China's Xinjiang Province crossed the frontier into the Soviet Union, fleeing the desperate economic conditions.[12]

| Sino-Soviet border conflict | |||||||||||||

|

Zhenbao Island and the border. | |||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 中蘇邊界衝突 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中苏边界冲突 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 珍寶島自衛反擊戰 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 珍宝岛自卫反击战 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Zhenbao Island self-defense | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Russian name | |||||||||||||

| Russian | Пограничный конфликт на острове Даманский | ||||||||||||

| Romanization | Pograničnyj konflikt na ostrove Damanskij | ||||||||||||

Amid heightening tensions, the Soviet Union and China began border talks. In spite of the fact that the Soviet Union had granted all of the territory of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo to Mao's communists in 1945, decisively assisting the communists in the Chinese Civil War, the Chinese now indirectly demanded territorial concessions on the basis that the 19th-century treaties transferring ownership of the sparsely populated Outer Manchuria, concluded by Qing dynasty China and Tsarist Russia, were "unequal", and amounted to annexation of supposedly rightful Chinese territory. Moscow would not accept this interpretation, but by 1964 the two sides did reach a preliminary agreement on the eastern section of the border, including Zhenbao Island, which would be handed over to China.

In July 1964, Mao Zedong, in a meeting with a Japanese socialist delegation, stated that Tsarist Russia had stripped China of vast territories in Siberia and the Far East as far as Kamchatka, which had never been controlled or claimed by a Chinese polity. Mao stated that China still had not presented a bill for this list. These comments were leaked to the public. Outraged, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev then refused to approve the border agreement.

Geography

The border dispute in the west centered on 52,000 square kilometres (20,000 sq mi) of Soviet-controlled land in the Pamirs that lay on the border of China's Xinjiang region and the Soviet Republic of Tajikistan. In 1892, the Russian Empire and the Qing Dynasty had agreed that the border would consist of the ridge of the Sarikol Range, but the exact border remained contentious throughout the 20th century. In the 1960s, the Chinese began to insist that the Soviet Union should evacuate the region.

Since around 1900, after the Treaty of Beijing, where Russia gained Outer Manchuria, the east side of the border had mainly been demarcated by three rivers, the Argun River from the triparty junction with Mongolia to the north tip of China, running southwest to northeast, then the Amur River to Khabarovsk from northwest to southeast, where it was joined by Ussuri River running south to north. The Ussuri River was demarcated in a non-conventional means: the demarcation line was on the right (Chinese) side of the river, putting the river with all islands in Russian possession. (“The modern method (used for the past 200 years) of demarcating a river boundary between states today is to set the boundary at either the median line (ligne médiane) of the river or around the area most suitable for navigation under what is known as the ‘thalweg principle.’”)[13]

China claimed these islands, as they were located on the Chinese side of the river (if demarcated according to international rule using shipping lanes). The USSR wanted (and by then, already effectively controlled) almost every single island along the rivers.

Prelude to a nuclear crisis and a people's war

During 1968, the Soviet Army had amassed along the 4,380 km (2,738 mi.) border with China — especially at the Xinjiang frontier, in north-west China, where the Soviets might readily induce Turkic separatists to insurrection. Militarily, in 1961, the USSR had 225,000 men and 200 aeroplanes at that border; in 1968, there were 375,000 men, 1,200 aeroplanes and 120 medium-range missiles. Moreover, PRC had 1.5 million men stationed at border and it had already tested its first nuclear weapon (the 596 Test in October 1964, at Lop Nur basin), the People's Liberation Army was militarily inferior to the Soviet Army as far as equipment was concerned. Yet, the Chinese adopted a asymmetric deterrence strategy that threatened a large-scale conventional “People’s War” in response to a Soviet counterforce first-strike.[1]

China’s superiority in sheer numbers of troops was the cornerstone of Beijing’s strategy to deter a Soviet nuclear attack.[1] Since 1949, Chinese military strategy as articulated by Chinese leader Mao Zedong continually emphasized the superiority of “man over weapons.” While weapons were certainly an important component of warfare, Mao argued that they were “not the decisive factor; it is people, not things, that are decisive. The contest of strength is not only a contest of military and economic power, but also a contest of human power and morale.”[1] In Mao’s view, non-material qualities, including subjectivity, creativity, flexibility, and high morale, were critical determinants in warfare.”[1]

The Soviets were not confident they could win such a conflict. A large-scale Chinese incursion could threaten key strategic centers in Blagoveshchensk, Vladivostok, and Khabarovsk, as well as crucial nodes of the Trans-Siberian Railroad.[1] According to Arkady Shevchenko, a high-ranking Russian defector to the United States, “The Politburo was terrified that the Chinese might make a large-scale intrusion into Soviet territory.[1] A nightmare vision of invasion by millions of Chinese made the Soviet leaders almost frantic. Despite our overwhelming superiority in weaponry, it would not be easy for the U.S.S.R. to cope with an assault of this magnitude.”[1] Given China’s “vast population and deep knowledge and experience in guerrilla warfare,” if the Soviets launched a major attack on China’s nuclear program they would surely become “mired in an endless war.”[1]

In fact, concerns about China’s strength in manpower and its “people’s war” strategy ran so deep that some bureaucrats in Moscow argued the only way to defend against a massive conventional onslaught was to use nuclear weapons.[1] Some even advocated deploying nuclear mines along the Sino-Soviet border.[1] By threatening to initiate a prolonged conventional conflict in retaliation for a nuclear strike, Beijing employed an asymmetric deterrence strategy intended to convince Moscow that the costs of an attack would outweigh the benefits.[1]

China had indeed found a potent threat. While most Soviet military specialists did not fear a Chinese nuclear reprisal, believing that China’s arsenal was so small, rudimentary, and vulnerable that it could not survive a first strike and carry out a retaliatory attack, there was great concern about China’s massive conventional army.[1] Nikolai Ogarkov, a senior Soviet military officer, believed that a massive nuclear attack “would inevitably mean world war.” Even a limited counterforce strike on China’s nuclear facilities was dangerous, Ogarkov argued, because a few nuclear weapons would “hardly annihilate” a country the size of China, and in response China would “fight unrelentingly.”[1]

Border conflict of 1969

The number of troops on both sides of the Sino-Soviet border increased dramatically after 1964.

Eastern border

On March 2, 1969, a group of People's Liberation Army (PLA) troops ambushed Soviet border guards on Zhenbao Island. The Soviets suffered 59 dead, including a senior colonel, and 94 wounded. The Chinese suffered 71 dead.[14] They retaliated on March 15 by bombarding Chinese troop concentrations on the Chinese bank of the Ussuri River and by storming Zhenbao Island.[14] The Soviets sent four then-secret T-62 tanks to attack the Chinese patrols on the island from the other side of the river. One of the leading tanks was hit and the tank commander was killed. On March 16, 1969, the Soviets entered the island to collect their dead; the Chinese held their fire. On March 17, 1969, the Soviets tried to recover the disabled tank, but their effort was repelled by the Chinese artillery.[14] On March 21, the Soviets sent a demolition team attempting to destroy the tank. The Chinese opened fire and thwarted the Soviets.[14] With the help of divers of the Chinese navy, the PLA pulled the T-62 tank onshore. The tank was later given to the Chinese Military Museum.[14] On March 15, 1969, the Chinese troops suffered significant losses, and were repelled from Zhenbao Island (Damansky Island). They did not return until September, 1969, when Soviet army men received the order to not to fire on them.[15]

Western border

Further border clashes occurred in August 1969, this time along the western section of the Sino-Soviet border in Xinjiang. After the Tasiti incident and the Bacha Dao incident, the Tielieketi Incident finally broke out. Chinese troops suffered 28 losses. Heightened tensions raised the prospect of an all-out nuclear exchange between China and the Soviet Union.[16] In the early 1960s, the United States had "probed" the level of Soviet interest in joint action against Chinese nuclear weapons facilities; now the Soviets probed what the United States' reaction would be if the USSR attacked the facilities.[17] While noting that "neither side wishes the inflamed border situation to get out of hand", the Central Intelligence Agency in August 1969 described the conflict as having "explosive potential" in the President's Daily Briefing.[18] The agency stated that "the potential for a war between them clearly exists", including a Soviet attack on Chinese nuclear facilities, while China "appears to view the USSR as its most immediate enemy".[19]

Consequences of 1969

As war fever gripped China, Moscow and Beijing took steps to lower the danger of a large-scale conflict. On September 11, 1969, Soviet Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin, on his way back from the funeral of the Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh, stopped over in Beijing for talks with his Chinese counterpart, Zhou Enlai. Symbolic of the frosty relations between the two communist countries, the talks were held in Beijing airport. The two premiers agreed to return ambassadors previously recalled and begin border negotiations.

The Chinese believe a different version of the conflict took place. The Chinese Cultural Revolution increased tensions between China and the USSR. This led to brawls between border patrols, and shooting broke out in March 1969. The USSR responded with tanks, APCs, and artillery bombardment. Over three days the PLA successfully halted Soviet penetration and eventually evicted all Soviet troops from Zhenbao island. During this skirmish the Chinese deployed two reinforced infantry platoons with artillery support. Chinese sources state the Soviets deployed some 60 soldiers and six BTR-60s and in a second attack some 100 troops backed up by ten tanks and 14 APCs including artillery.[14] The PLA had prepared for this confrontation for two to three months.[20] From among the units, the PLA selected 900 soldiers commanded by army staff members with combat experience.[21] They were provided with special training and special equipment. Then they were secretly dispatched to take position on Zhenbao island in advance.[6]

On 2 March when the Soviets conducted their offensive they were hopelessly outnumbered by the Chinese.[6] Chinese General Chen Xilian stated the Chinese had won a clear victory on the battlefield.[6] On 15 March the Soviets dispatched another 30 soldiers and six combat vehicles to Zhenbao island.[22] After an hour of fighting the Chinese had destroyed two of the Soviet vehicles.[22] A few hours later the Soviets sent a second wave with artillery support. The Chinese would destroy five more Soviet combat vehicles.[22] A third wave would be repulsed by effective Chinese artillery which destroyed one Soviet tank and four APCs while damaging two other APCs.[22] The Chinese proved once again to be better prepared than the Soviets were.[22] The Chinese gave their soldiers the credit for their victories over the better equipped Soviets citing superior intellect and spirit of the Chinese soldier.[23] Chinese propaganda described the Soviet troops as being politically degenerated and morally decadent.[23]

The view on the reasoning and consequences of the conflict differ between western and Russian historians. Western historians believe the events at Zhenbao Island and the subsequent border clashes in Xinjiang caused Mao to re-appraise China's foreign policy and to seek rapprochement with the United States,[16] while Russian historians point out that the consequences of the conflict stem directly from the desire of the PRC to take a leading role in the world and strengthen ties with the US. Such a local conflict with the USSR would be a sign of a split with the USSR and signal the US that China was ready for dialogue.[24] The PRC began ideological preparation for the split with the USSR in the late 1950s,[25] and the Soviet Border Service started to report intensifying Chinese military activity in the region during the early 1960s.

After the conflict, America showed actual interest in strengthening ties with the Chinese government by secretly sending Henry Kissinger to China for a meeting with Prime Minister Zhou Enlai in 1971, during the so-called Ping Pong Diplomacy, paving the way for Richard Nixon to visit China and meet with Mao Zedong in 1972.[26]

China's relations with the USSR remained sour after the conflict, despite the border talks, which began in 1969 and lasted inconclusively for a decade. Domestically, the threat of war, caused by the border clashes, inaugurated a new stage in the Cultural Revolution; that of China's thorough militarization. The 9th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, held in the aftermath of the Zhenbao Island incident, confirmed Defense Minister Lin Biao as Mao's heir-apparent. Following the events of 1969, the Soviet Union further increased its forces along the Sino-Soviet border, and in the Mongolian People's Republic.

Overall, the Sino-Soviet confrontation, which reached its peak in 1969, paved the way to a profound transformation in the international political system.

Chinese combat heroes

During the Zhenbao Island clashes with the Soviet Army in March 1969 one Chinese RPG team, Hua Yujie and his assistant Yu Haichang destroyed four Soviet APCs and achieved more than ten kills.[27] Hua and Yu received the accolade "Combat Hero" from the CMC, and their action was commemorated on a postage stamp.[27]

Border negotiations in the 1990s and beyond

Serious border demarcation negotiations did not occur until shortly before the end of the Soviet Union in 1991. In particular, both sides agreed that Zhenbao Island belonged to China. (Both sides claimed the island was under their control at the time of the agreement.) On October 17, 1995, an agreement over the last 54 kilometres (34 mi) stretch of the border was reached, but the question of control over three islands in the Amur and Argun rivers was left to be settled later.

In a border agreement between Russia and China signed on October 14, 2003, that dispute was finally resolved. China was granted control over Tarabarov Island (Yinlong Island), Zhenbao Island, and approximately 50% of Bolshoy Ussuriysky Island (Heixiazi Island), near Khabarovsk. China's Standing Committee of the National People's Congress ratified this agreement on April 27, 2005, with the Russian Duma following suit on May 20. On June 2, Chinese Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing and Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergei Lavrov exchanged the ratification documents from their respective governments.[28]

On July 21, 2008, Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi and his Russian counterpart, Sergei Lavrov, signed an additional Sino-Russian Border Line Agreement marking the acceptance of the demarcation the eastern portion of the Chinese-Russian border in Beijing, China. An additional protocol with a map affiliated on the eastern part of the borders both countries share was signed. The agreement also includes the PRC gaining ownership of Yinlong/Tarabarov Island and half of Heixiazi/Bolshoi Ussuriysky Island.[29]

In the 21st century the Chinese version of the conflict, present on many official websites, describes the events of March 1969 as a Soviet aggression against China. Russian authorities, afraid of provoking China's discontent, do not protest against such claims.[30]

See also

- History of the Soviet Union (1964–1982)

- History of the People's Republic of China

- Foreign relations of the People's Republic of China

- Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang

- Xinjiang War (1937)

- Pei-ta-shan Incident

Notes

People & Events: Sino-Soviet Border Disputes (March 1969) PBS

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 https://www.cna.org/CNA_files/PDF/D0022974.A2.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ibiblio.org/chinesehistory/contents/03pol/c04s05.html

- ↑ See (Russian) D. S. Ryabushkin, Мифы Даманского. Мoscow: АСТ, 2004, pp. 151, 263-264.

- ↑ Kuisong p.25,26,29

- ↑ Kuisong p.25

- 1 2 3 4 Kuisong p.29

- ↑ John Baylis et al. Contemporary Strategy: Vol. 2, The Nuclear Powers. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1987, p. 89.

- ↑ name=ryabushkinbr>See (Russian) D. S. Ryabushkin, Мифы Даманского. Мoscow: АСТ, 2004, pp. 151, 263-264.

- ↑ People.com.cn. "People.com.cn." 1969年珍宝岛自卫反击战. Retrieved on 2009-11-05.

- ↑ Millward, James (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. p. 208.

- ↑ Forbes, Andrew (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. CUP Archive. pp. 175, 178, 188.

- ↑ Bellér-Hann, Ildikó (2007). Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 38–41.

- ↑ Shah, Sikander Ahmed (February 2012). "River Boundary Delimitation and the Resolution of the Sir Creek Dispute Between Pakistan and India" (PDF). Vermont Law Review. 34 (357): 364. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Chinese People's Liberation Army since 1949 by Benjamin Lai

- ↑ Moraly, A (2011). International Robbery of U.S. Wealth. Xlibris Corporation. p. 184. ISBN 9781456896867. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- 1 2 Kuisong, Yang. "The Sino-Soviet Border Clash of 1969: From Zhenbao Island to Sino-American Rapprochement," Cold War History 1 (2000): 21-52.

- ↑ Burr, William. "The Sino-Soviet Border Conflict, 1969" National Security Archive, 12 June 2001.

- ↑ "The President's Daily Brief" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. 1969-08-14. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ "The President's Daily Brief" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. 1969-08-13. p. 3. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ Kuisong p.28

- ↑ Kuisong p.28-29

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kuisong p.26

- 1 2 Kuisong p.27

- ↑ Goldstein, Lyle J. "Return to Zhenbao Island: Who Started Shooting and Why it Matters." The China Quarterly 168 (December 2001): pp. 985-97.

- ↑ "Bloodshed on Damansky (Кровопролитие на Даманском)". Konkurent.ru. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- ↑ "Henry Kissinger plays ping-pong". Tabletennis.hobby.ru. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- 1 2 Benjamin Lai p.12

- ↑ "China, Russia solve all border disputes". Xinhua. June 2, 2005. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- ↑ "China, Russia complete border survey, determination". Xinhua. July 21, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- ↑ "Новейшая фальсификация Китаем истории конфликта на острове Даманский и бездействие МИД России".

External links

- Map showing some of the disputed areas

- Damanski-Zhenbao website

- Sino-Soviet Border Conflict, 1969

- How Comrade Mao was perceived in the Soviet Union

- The Sino-Soviet Border Conflict: Deterrence, Escalation, and the Threat of Nuclear War in 1969

- The Sino-Soviet Border Clash of 1969: From Zhenbao Island to Sino-American Rapprochement