South Downs

| South Downs | |

|---|---|

.jpg) The Seven Sisters, near Eastbourne, viewed from Seaford Head | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Butser Hill |

| Elevation | 271 m (889 ft) |

| Coordinates | 50°58′39.61″N 0°58′53.4″W / 50.9776694°N 0.981500°W |

| Dimensions | |

| Area | 670 km2 (260 sq mi) |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | Old English dūn, meaning 'hill' |

| Geography | |

| Country | England |

| State/Province | Hampshire, East Sussex, West Sussex |

| Range coordinates | 50°55′N 0°30′W / 50.92°N 0.5°WCoordinates: 50°55′N 0°30′W / 50.92°N 0.5°W |

| Parent range | Southern England Chalk Formation |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Alpine orogeny |

| Age of rock | Cretaceous |

| Type of rock | chalk |

The South Downs are a range of chalk hills that extends for about 260 square miles (670 km2)[1] across the south-eastern coastal counties of England from the Itchen Valley of Hampshire in the west to Beachy Head, near Eastbourne, East Sussex, in the east. It is bounded on its northern side by a steep escarpment, from whose crest there are extensive views northwards across the Weald. The South Downs National Park forms a much larger area than the chalk range of the South Downs and includes large parts of the Weald.

The South Downs are characterised by rolling chalk downland with close-cropped turf and dry valleys, and are recognised as one of the most important chalk landscapes in England.[2] The range is one of the four main areas of chalk downland in southern England.[3]

The South Downs are relatively unpopulated compared to South East England as a whole, although in Sussex there has been large-scale urban encroachment onto the chalk downland by major seaside resorts, including most notably Brighton and Hove.

The South Downs have been inhabited since ancient times and at periods the area has supported a large population, particularly during Romano-British times. There is a rich heritage of historical features and archaeological remains, including defensive sites, burial mounds and field boundaries. Within the South Downs Environmentally Sensitive Area there are thirty-seven Sites of Special Scientific Interest, including large areas of chalk grassland.[4]

The grazing of sheep on the thin, well-drained chalk soils of the Downs over many centuries and browsing by rabbits resulted in the fine, short, springy turf, known as old chalk grassland, that has come to epitomise the South Downs today. Until the middle of the 20th century, an agricultural system operated by downland farmers known as 'sheep-and-corn farming' underpinned this: the sheep (most famously the Southdown breed) of villagers would be systematically confined to certain corn fields to improve their fertility with their droppings and then they would be let out onto the downland to graze. However, starting in 1940 with government measures during World War II to increase domestic food production and continuing into the 1950s, much grassland was ploughed up for arable farming, fundamentally changing the landscape and ecology, with the loss of much biodiversity. As a result, while old chalk grassland accounted for 40-50% of the eastern Downs before the war, only 3-4% survives.[5] This and development pressures from the surrounding population centres ultimately led to the decision to create the South Downs National Park, which came into full operation on 1 April 2011, to protect and restore the Downs.

The South Downs have also been designated as a National Character Area (NCA 125) by Natural England. It is bordered by the Hampshire Downs, the Wealden Greensand, the Low Weald and the Pevensey Levels to the north and the South Hampshire Lowlands and South Coast Plain to the south.[6]

The downland is an extremely popular recreational destination, particularly for walkers, horseriders and mountain bikers. A long distance footpath and bridleway, the South Downs Way, follows the entire length of the chalk ridge from Winchester to Eastbourne, complemented by many interconnecting public footpaths and bridleways.

Toponymy

The term 'downs' is from Old English dūn, meaning 'hill'. The word acquired the sense of 'elevated rolling grassland' around the fourteenth century.[7] These hills are prefixed 'south' to distinguish them from another chalk escarpment, the North Downs, which runs roughly parallel to them about 30 miles (48 km) away on the northern edge of the Weald.

Geology

The South Downs are formed from a thick band of chalk which was deposited during the Cretaceous Period around sixty million years ago within a shallow sea which extended across much of northwest Europe. The rock is composed of the microscopic skeletons of plankton which lived in the sea, hence its colour. The chalk has many fossils, and bands of flint occur throughout the formation.[8] The Chalk is divided into the Lower, Middle and Upper Chalk, a thin band of cream-coloured nodular chalk known as the Melbourn Rock marking the boundary between the Lower and Middle units.

The strata of southeast England, including the Chalk, were gently folded during a phase of the Alpine Orogeny to produce the Weald-Artois Anticline, a dome-like structure with a long east-west axis. Erosion has removed the central part of the dome, leaving the north-facing escarpment of the South Downs along its southern margin with the south-facing chalk escarpment of the North Downs as its counterpart on the northern side, as shown on the diagram. Between these two escarpments the anticline has been subject to differential erosion so that geologically distinct areas of hills and vales lie in roughly concentric circles towards the centre; these comprise the Greensand Ridge, most prominent on the north side of the Weald, where it includes Leith Hill, the highest hill in south-east England, the low-lying clay vales of the Low Weald, formed of less resistant Weald Clay, and finally the more highly resistant sandstones of the High Weald at the centre of the anticline, whose elevated forest ridge includes most notably Ashdown Forest.[9]

The chalk, being porous, allows water to soak through; as a result there are many winterbournes along the northern edge.

Geography

The South Downs are a long chalk escarpment that stretches for over 70 miles (110 km), rising from the valley of the River Itchen near Winchester, Hampshire, in the west to Beachy Head near Eastbourne, East Sussex, in the east.[10] Behind the steep north-facing scarp slope, the gently inclined dip slope of undulating chalk downland extends for a distance of up to 7 miles (11 km) southwards. Viewed from high points further north in the High Weald and on the North Downs, the scarp of the South Downs presents itself as a steep wall that bounds the horizon, with its grassland heights punctuated with clumps of trees (such as Chanctonbury Ring).

In the west, the chalk ridge of the South Downs merges with the North Downs to form the Hampshire Downs. In the east, the escarpment terminates at the English Channel coast between Seaford and Eastbourne, where it produces the spectacular white cliffs of Seaford Head, the cross-section of dry valleys known as the Seven Sisters and Beachy Head, the highest chalk sea cliff in Britain at 162 metres (531 ft) above sea level.

The South Downs may be said to have three main component parts: the East Hampshire Downs, the Western Downs and the Eastern Downs, together with the river valleys that cut across them and the land immediately below them, the scarpfoot.[11] The Western and Eastern Downs are often collectively referred to as the Sussex Downs. The Western Downs, lying west of the River Arun, are much more wooded, particularly on the scarp face, than the Eastern Downs. The bare Eastern Downs – the only part of the chalk escarpment to which, until the late 19th century, the term "South Downs" was usually applied – have come to epitomise, in literature and art, the South Downs as a whole and which have been the subject matter of such celebrated writers and artists as Rudyard Kipling (the "blunt, bow-headed, whale-backed downs") and Eric Ravilious.[12]

Four river valleys cut through the South Downs, namely those of the rivers Arun, Adur, Ouse and Cuckmere, providing a contrasting landscape. Chalk aquifers and to a lesser extent winterbourne streams supply much of the water required by the surrounding settlements. Dew ponds, artificial ponds for watering livestock, are a characteristic feature on the downland.

The highest point on the South Downs is Butser Hill, whose summit is 270 metres (890 ft) above sea level. The plateau-like top of this vast, irregularly shaped hill, which lies just south of Petersfield, Hampshire, was in regular use through prehistory. It has been designated as a National Nature Reserve.

Within the boundary of the South Downs National Park, which includes parts of the western Weald to the north of the South Downs, the highest point is Blackdown, West Sussex, which rises to 280 metres (919 ft) above sea level. However, Blackdown geologically is not part of the South Downs but instead forms part of the Greensand Ridge on the Weald's western margins.

A list of those points on the South Downs above 700 feet (210 m), going from west to east, is given below.

| Name of hill | Nearest settlement | Height | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butser Hill | Petersfield | 270 m (886 ft) | Highest point in the South Downs proper. |

| West Harting Down | South Harting | 215 m (707 ft) | |

| Beacon Hill | South Harting | 242 m (793 ft) | |

| Linch Down | Bepton | 248 m (814 ft) | |

| Littleton Down | East Lavington | 255 m (836 ft) | The summit, Crown Teglease, is the highest point on the Sussex Downs. |

| Glatting Beacon | Sutton | 245 m (803 ft) | |

| Chanctonbury Hill | Washington | 238 m (782 ft) | Site of Chanctonbury Ring hill fort |

| Truleigh Hill | Upper Beeding | 216 m (708 ft) | |

| Ditchling Beacon | Ditchling | 248 m (814 ft) | |

| Firle Beacon | Firle | 217 m (713 ft) | |

History

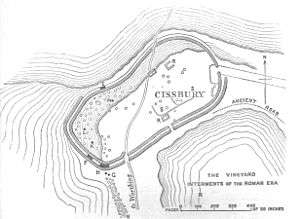

Archaeological evidence has revealed that the Downs have been inhabited and utilised for thousands of years. Neolithic flint mines such as Cissbury, burial mounds such as the Devil's Jumps and Devil's Humps, and hill forts like Chanctonbury Ring are strong features in the landscape.[13][14]

It has been estimated that the tree cover of the Downs was cleared over 3000 years ago, and the present closely grazed turf is the result of continual grazing by sheep.

National park

Proposals to create a national park for the South Downs date back to the 1940s. However, it was not until 1999 that the idea received firm government support. After a public enquiry that took place between 2003 and 2009, the government announced its decision to make the South Downs a national park on 31 March 2009. The South Downs National Park finally came into operation on 1 April 2011. Within its boundary are included not only the South Downs proper but also part of the western Weald, a geologically and ecologically quite different district.

The South Downs National Park has replaced two Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB)s: East Hampshire AONB and Sussex Downs AONB. During the enquiry process a number of boundary questions were considered, so that the National Park contains areas not in the former AONBs, and vice versa.

National Nature Reserves

The South Downs contain a number of National Nature Reserves (NNRs).[15]

The NNRs on the Sussex Downs comprise Kingley Vale, near Chichester, said by Natural England to contain one of the finest yew forests in Europe, including a grove of ancient trees which are among the oldest living things in Britain (the reserve is also one of the most important archaeological sites in southern England, with 14 Scheduled Ancient Monuments); Castle Hill, between Brighton and Lewes, an important example of ancient, traditionally managed grassland; Lewes Downs (Mount Caburn), a traditionally managed chalk downland (and also an important archaeological site); and Lullington Heath, on the northern fringe of Friston Forest north-west of Eastbourne, one of the largest areas of chalk heath in Britain.

The NNRs on the East Hampshire Downs comprise Butser Hill, near Petersfield, a large area of chalk grassland on the highest point in the South Downs (a large area is also designated as a Scheduled Ancient Monument reflecting its historical significance, particularly in the Bronze and Iron Ages); Old Winchester Hill, a lowland grassland on the west and south facing scarp slopes of the Meon valley; and Beacon Hill, a high quality chalk grassland 5 km west of Old Winchester Hill.

Tourism, leisure and sport

In 1923 the Society of Sussex Downsmen (now the South Downs Society) was formed with the aim of protecting the area's unique landscape.[16]

The South Downs are a popular area for ramblers with a network of over 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of well-managed, well-signed and easily accessible trails. The principal bridleway, and longest of them, is the South Downs Way.[17] The Monarch's Way, having originated at Worcester, crosses the South Downs and ends at Shoreham-by-Sea.[18]

Sports undertaken on the Downs include paragliding, mountain-biking, horse riding and walking.[19] The popular Beachy Head Marathon (formerly Seven Sisters Marathon), a hilly cross-country marathon, takes place each autumn on the eastern Downs, starting and finishing in Eastbourne. The South Downs Trail Marathon starts in the village of Slindon (near Arundel) and ends at the Queen Elizabeth Country Park (to the south of Petersfield.)

Longer events that take in the South Downs Way include a 100-mile running 'ultramarathon' and mountain biking 75 mile night time race from Beachy Head to Queen Elizabeth Country Park.

Landmarks

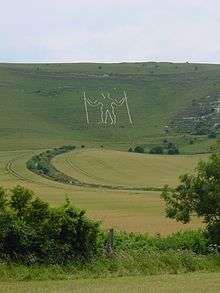

Two of the landmarks on the Downs are the Long Man of Wilmington, a chalk carved figure, and Clayton Windmills. There is also a war memorial, The Chattri, dedicated to Indian soldiers who died in the Brighton area, having been brought there for treatment after being injured fighting on the Western Front in the First World War.

South Downs in literature

Rudyard Kipling who lived at Rottingdean described the South Downs as "Our blunt, bow-headed whale-backed Downs".[20] Writing in 1920 in his poem The South Country, poet Hilaire Belloc describes the South Downs as "the great hills of the South Country".[21] In On The South Coast, poet Algernon Charles Swinburne describes the South Downs as "the green smooth-swelling unending downs".[22]

The naturalist-writer William Henry Hudson wrote that "during the whole fifty-three mile length from Beachy Head to Harting the ground never rises above a height of 850 feet, but we feel on top of the world".[23]

Poet Francis William Bourdillon also wrote a poem "On the South Downs".[24] The South Downs have been home to several writers including Jane Austen who lived at Chawton on the edge of the Downs in Hampshire. The Bloomsbury Group often visited Monk's House in Rodmell, the home of Virginia Woolf in the Ouse valley. Alfred, Lord Tennyson had a second home at Aldworth, on Blackdown; geologically part of the Weald, Blackdown lies north of the South Downs but is included in the South Downs National Park.

In the introduction to Arthur Conan Doyle's short story collection "His Last Bow", Dr. Watson states that Sherlock Holmes has retired to a small farm upon the Downs near Eastbourne. In "His Last Bow" itself, Holmes states that he "lives and keeps bees upon the South Downs". Furthermore, the short story "The Lion's Mane" is about a case which Holmes solves whilst living there.

The author Graham Greene's, first published novel, 'The Man Within' (1929) is set largely on and around the South Downs. The book's principal character, 'Andrews', travels by foot across the Downs to reach Lewes and attend the Assizes. Greene provides a detailed description of both the landscape and its 'feel'.

Gallery

- Looking east along the Downs towards the Devil's Dyke, Sussex

South Downs close to Beachy Head

South Downs close to Beachy Head Trig Point on Kithurst Hill West Sussex. Located on the South Downs Way above the village of Storrington. 699 ft high at the summit.

Trig Point on Kithurst Hill West Sussex. Located on the South Downs Way above the village of Storrington. 699 ft high at the summit. Typical topography (Treyford Hill): steep wooded northern slope (left), gently sloping southern slope of pasture and woodland.

Typical topography (Treyford Hill): steep wooded northern slope (left), gently sloping southern slope of pasture and woodland.

Notes

- ↑ The land area figure cited here relates to the South Downs Environmentally Sensitive Area, as defined by Natural England for its Environmentally Sensitive Area scheme (launched 1987, but now closed to new applicants, having been replaced by the Environmental Stewardship scheme). The South Downs ESA is referred to by Peter Brandon when he defines the extent of the South Downs; see Brandon (1998), p.1.

- ↑ Source: Natural England, South Downs ESA.

- ↑ The others being the North Downs of Kent and Surrey; the Chilterns to the north-west of London; and the North Wessex Downs of Wiltshire, Dorset, Hampshire and Berkshire.

- ↑ Source: Natural England.

- ↑ Peter Brandon, The South Downs (Halsgrove, Tiverton, 2003), p.51.

- ↑ South East and London National Character Area map at www.naturalengland.org.uk. Accessed on 3 Apr 2013.

- ↑ Downs, Etymology online, retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ Shepherd, Roy, Chalk formation fossils, Discovering fossils, retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50K map sheet 318/333 Brighton & Worthing.

- ↑ There are various definitions of where in the west the South Downs really begin. The South Downs National Park boundary reaches to the eastern edge of Winchester, whereas for Brandon (1998), the South Downs begin east of the valley of the River Meon, with Old Winchester Hill marking the beginning of the chalk ridge.

- ↑ Brandon 1998, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ Brandon 1998, p. 3.

- ↑ South Downs, English Heritage, retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ South Downs Way, nationaltrail.co.uk, retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ See Natural England website for more details of all the National Nature Reserves mentioned in this section.

- ↑ South Downs Society website, retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ South Downs Way: description of the route.

- ↑ South Downs Way National Trail, Ramblers Association, retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ Outdoor activities, South Downs National Park Authority, retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ Kipling, Rudyard (1907), Collected Verse of Rudyard Kipling, New York: Doubleday, Page and Co., p. 123.

- ↑ Walters, L. D'O., ed. (1920), An anthology of recent poetry, New York: Dodd and Mead, p. 9.

- ↑ Swinburne, Algernon Charles (1911), Poems of Algernon Charles Swinburne. Volume VI, London: Chatto and Windus, p. 147.

- ↑ McCarthy, Michael (10 November 2003), "The wild, serene Downs fight against protection", The Independent, London.

- ↑ Francis William Bourdillon: On the South Downs, Poem Hunter, retrieved 5 April 2011.

References

- Brandon, Peter (1998), The South Downs, Chichester, UK: Phillimore, ISBN 1-86077-069-X.

Further reading

- Hudson, W.H. (1901), Nature in Downland, London: Longmans and Green.

External links

South Downs travel guide from Wikivoyage

South Downs travel guide from Wikivoyage- Sussex South Downs Guide