Wayland the Smith

In Norse mythology, Wayland the Smith (Old English: Wēland; Old Norse: Völundr, Velentr; Old High German: Wiolant ; Proto-Germanic: *Wēlandaz, from *Wēla-nandaz, lit. "battle-brave"[1]) is a legendary master blacksmith, described by Jessie Weston as "the weird and malicious craftsman, Weyland".[2] In Old Norse sources, Völundr appears in Völundarkviða, a poem in the Poetic Edda, and in Þiðrekssaga, and his legend is also depicted on the Ardre image stone VIII. In Old English sources, he appears in Deor, Waldere and in Beowulf and the legend is depicted on the Franks Casket. He is mentioned in the German poems about Dietrich von Bern as the Father of Witige.[3]

Old Norse reference

According to Völundarkviða, the king of the Lapps had three sons: Wayland and his two brothers Egil and Slagfiðr. In one version of the myth, the three brothers lived with three Valkyries: Ölrún, Hervör alvitr and Hlaðguðr svanhvít. After nine years, the Valkyries left their lovers. Egil and Slagfiðr followed, never to return. In another version, Wayland married the swan maiden Hervör, and they had a son, Heime, but Hervör later left Wayland. In both versions, his love left him with a ring. In the former myth, he forged seven hundred duplicates of this ring.

Later, King Niðhad captured Wayland in his sleep in Nerike and ordered him hamstrung and imprisoned on the island of Sævarstöð. There Wayland was forced to forge items for the king. Wayland's wife's ring was given to the king's daughter, Bodvild. Nidud wore Wayland's sword.

In revenge, Wayland killed the king's sons when they visited him in secret, fashioned goblets from their skulls, jewels from their eyes, and a brooch from their teeth. He sent the goblets to the king, the jewels to the queen and the brooch to the king's daughter. When Bodvild took her ring to Wayland for mending, he took the ring and raped her, fathering a son. He then escaped, using wings he made.

Wayland (Völund) made the magic sword Gram (also named Balmung and Nothung) and the magic ring that Thorsten retrieved.

Old English references

The Old English poem Deor, which recounts the famous sufferings of various figures before turning to those of Deor, its author, begins with "Welund":

- Welund tasted misery among snakes.

- The stout-hearted hero endured troubles

- had sorrow and longing as his companions

- cruelty cold as winter - he often found woe

- Once Nithad laid restraints on him,

- supple sinew-bonds on the better man.

- That went by; so can this.

- To Beadohilde, her brothers' death was not

- so painful to her heart as her own problem

- which she had readily perceived

- that she was pregnant; nor could she ever

- foresee without fear how things would turn out.

- That went by, so can this.[4]

Weland had fashioned the mail shirt worn by Beowulf according to lines 450–455 of the epic poem of the same name:

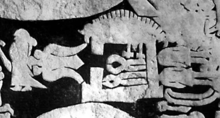

The Franks Casket is one of a number of other Anglo-Saxon references to Wayland, whose story was evidently well known and popular, although no extended version in Old English has survived. The reference in Waldere is similar to that in Beowulf - the hero's sword was made by Weland[5] - while Alfred the Great in his translation of Boethius asks plaintively: "What now are the bones of Wayland, the goldsmith preeminently wise?".[6] In the front panel of the Franks Casket, incongruously paired with an Adoration of the Magi, Wayland stands at the extreme left in the forge where he is held as a slave by King Niðhad, who has had his hamstrings cut to hobble him. Below the forge is the headless body of Niðhad's son, who Wayland has killed, making a goblet from his skull; his head is probably the object held in the tongs in Wayland's hand. With his other hand Wayland offers the goblet, containing drugged beer, to Bodvild, Niðhad's daughter, whom he then rapes when she is unconscious. Another female figure is shown in the centre; perhaps Wayland's helper, or Bodvild again. To the right of the scene Wayland (or his brother) catches birds; he then makes wings from their feathers, with which he is able to escape.[7]

During the Viking Age in northern England, Wayland is depicted in his smithy, surrounded by his tools, at Halton, Lancashire, and fleeing from his royal captor by clinging to a flying bird, on crosses at Leeds, West Yorkshire, and at Sherburn-in-Elmet and Bedale, both in North Yorkshire.[8][9] English literature was also aware of his giant father Wade.[10]

Toponyms

Wayland is associated with Wayland's Smithy, a burial mound in the Berkshire Downs.[11] This was named by the English, but the megalithic mound significantly predates them. It is from this association that the superstition came about that a horse left there overnight with a small silver coin (groat) would be shod by morning. This superstition is mentioned in the first episode of Puck of Pook's Hill by Rudyard Kipling, "Weland's Sword", which narrates the rise and fall of the god.[12]

Swords described as having been forged by Wayland

John Gehring (1883)

- Four are mentioned by name in the Karlamagnus Saga

- Almace, the sword of Archbishop Turpin.

- Curtana, the sword of Ogier the Dane

- Durandal, the sword of Roland (N.B. in Orlando Innamorato Durandal is said to have been originally the sword of Hector of Troy.)

- Mimung, which he forged to fight the rival smith Amilias, according to Thidrekssaga, and later came into the possession of Landri or Landres, nephew of Charlemagne.

- Another in the Poetic Edda

- Gram, the sword of Sigmund, which would be destroyed by Odin, and is later reforged by Regin and used by Sigmund's son Sigurd to slay the dragon Fafnir, according to the Völsunga saga.

- Six are referenced in early arthurian and chivalric romance chanson de geste poetry.

- Adylok / Hatheloke, the sword of Torrent of Portyngale, according to Torrent of Portyngale.

- Caliburn, in Mary Stewart's Arthurian Legend, is the sword of Macsen, Merlin, and Arthur.

- Merveilleuse, the hero's sword in the Chanson de Doon de Mayence was forged by "Un ouvrier de Galan", a journeyman of Wayland's.

- The unnamed sword of the hero in the Chanson de Gui de Nanteuil.

- The unnamed sword of Huon of Bordeaux, according to Lord Berners.

- More are referenced in more modern adaptations, including

- An unnamed sword whose history is related by Rudyard Kipling in Puck of Pook's Hill.

- Albion, sword of Robin Hood, and its six partners in Robin of Sherwood.

See also

References

- ↑ see Hellmut Rosenfeld, Der Name Wieland, Beiträge zur Namenforschung (1969).

- ↑ J. Weston, 'Legendary Cycles of the Middle Age', in J. R. Tanner ed, The Cambridge Medieval History Vol VI (Cambridge 1929) p. 842

- ↑ J. Weston, 'Legendary Cycles of the Middle Age', in J. R. Tanner ed, The Cambridge Medieval History Vol VI (Cambridge 1929) p. 841

- ↑ Translation by Steve Pollington

- ↑ R.K. Gordon, ed. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. (London: Dent) 1954:65. Partial text of the Walder fragments in modern English - see the start of fragment A for Wayland

- ↑ Quoted in T. A. Shippey, The Road to Middle-Earth (1992) p. 27

- ↑ G. Henderson, Early Medieval Art, 1972, rev. 1977, Penguin, p. 157

- ↑ All noted in Richard Hall, Viking Age Archaeology (series Shire Achaeology) 1995:40.

- ↑ "Depictions of Wayland's Wings". Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ J. Weston, 'Legendary Cycles of the Middle Age', in J. R. Tanner ed, The Cambridge Medieval History Vol VI (Cambridge 1929) p. 841

- ↑ T. Shippey, The Road to Middle-Earth (1992) p. 27

- ↑ T. Shippey, The Road to Middle-Earth (1992) p. 302

Other sources

- Heaney, Seamus (2000). Beowulf: A New Verse Translation. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32097-8.

- Larrington, Carolyne (transl.) (1996). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2.

- Mortensson-Egnund, Ivar (transl.) (2002). Edda: The Elder Edda and the Prose Edda. Oslo: Samlaget. ISBN 82-521-5961-3.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Wayland the Smith. |

- Article on Wayland the Smith; also deals with Egil

- Austin Simmons, The Cipherment of the Franks Casket (PDF)

- Weland on the Franks Casket; essay on the Saga

- Völundarkviða - Heimskringla.no