Vair

_Nord-France.svg.png)

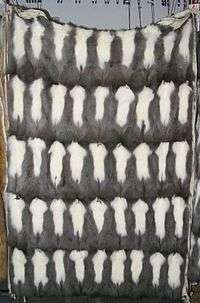

Vair (/vɛər/; from Latin varius "variegated") is a fur, and a set of patterns in heraldry. It represents a kind of fur common in the Middle Ages, made from the greyish-blue backs of squirrels sewn together with the animals' white underbellies. Vair is the second-most common fur in heraldry, after ermine.

Origins

The word vair, with its variant forms veir and vairé, was brought into Middle English from Old French, from Latin varius "variegated",[1] and has been alternatively termed variorum opus (Latin, meaning "variegated work").[2]

The squirrel in question is a variety of the Eurasian red squirrel, Sciurus vulgaris. In the coldest parts of Northern and Central Europe, especially the Baltic region, the winter coat of this squirrel is blue-grey on the back and white on the belly, and was much used for the lining of cloaks called mantles. It was sewn together in alternating cup-shaped pieces of back and belly fur, resulting in a pattern of grey-blue and grey-white which, when simplified in heraldic drawing and painting, became blue and white in alternating pieces.[2]

Dark morph of Eurasian red squirrel

Dark morph of Eurasian red squirrel Enamel image from the tomb of Geoffrey, Count of Anjou showing a vair-lined mantle

Enamel image from the tomb of Geoffrey, Count of Anjou showing a vair-lined mantle

Variations

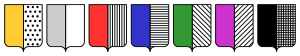

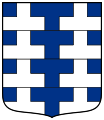

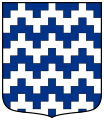

In early heraldry, vair was represented by means of straight horizontal lines alternating with wavy lines. Later it mutated into a pattern of bell or shield-like shapes. The early form is still sometimes found, under the name vair ondé (wavy vair) or vair ancien (ancient vair).

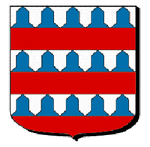

When vair occurs in two tinctures other than argent and azure, or when it includes three or even four distinct tinctures,[3] it is blazoned vairy (or vairé) [tincture] and [tincture]. There are three forms of vair in which the pieces are arranged differently: countervair, vair in pale and vair en pointe.

The height of a row of vair is not strictly specified and thus can variate, but is typically about one-fifth that of the shield. Despite not being officially sized, the number of rows in a vair pattern is specific : for six rows or more, the term menu-vair is to be used. This is the origin of the English word "miniver", which was the general word for the fur lining used for robes of state. Vair of fewer than four rows is to be called beffroi (the French for "belfry"), probably from the resemblance of a piece of vair to a bell. Vair of two rows, called gros-vair, is also occasionally seen, although in most cases considered as a beffroi.

Vairé gules and or

Vair ancien

Counter-vair

Vair in pale

Vair en pointe

Potent

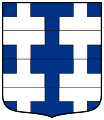

Potent is a similar pattern, consisting of T-shapes. It is believed to originate from badly-drawn vair. The name comes from an old word for a crutch, based on the resemblance of a crutch to a T-shape. It is found but rarely, its variations being rarer still.

Potent

Counter-potent

Potent in pale

Potent en pointe

Counter-potenté gules and or

Cinderella's slippers

It is widely believed that Perrault's version of the fairytale "Cinderella" was mistranslated into English. The story says that the original French had the slippers made of vair (fur), which was misread as the homophonous verre (glass).[4] This story has been disputed.[5][6]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vair (fur). |

References

- ↑ "Vair". American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed. New York:Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000.

- 1 2 Veale, Elspeth M.: The English Fur Trade in the Later Middle Ages, p. 224.

- ↑ de Bara, Hiérosme (1581). Le Blason des Armoiries. p. 14.

- ↑ One example: Parker, James (1894). A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry: Vair. Retrieved 9 June 2011..

- ↑ Mikkelson, Barbara; Mikkelson, David (12 July 2007). "Glass Slippers". Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ↑ The QI Book of General Ignorance (Pocket Edition). Faber and Faber Limited. 2008. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-571-24139-2.

This article incorporates text from A. C. Fox-Davies' 1914 edition of Charles Boutell's

- The Handbook to English Heraldry at Project Gutenberg, which is in the public domain in the United States.

- Veale, Elspeth M.: The English Fur Trade in the Later Middle Ages, 2nd Edition, London Folio Society 2005. ISBN 0-900952-38-5

- comment about the double translation in Cinderella