Ventricular hypertrophy

| Ventricular hypertrophy | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | cardiology |

| ICD-10 | I51.7 |

| ICD-9-CM | 429.3 |

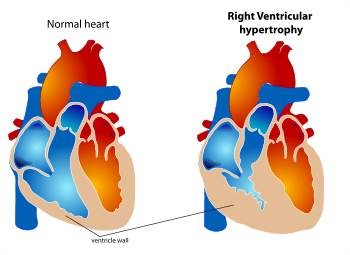

Ventricular hypertrophy (VH) is thickening of the walls of a ventricle (lower chamber) of the heart.[1][2] Although left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is more common, right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) can also occur, as can hypertrophy of both ventricles, that is, biventricular hypertrophy (BVH).

Ventricular hypertrophy can be part of various syndromes caused by any of various underlying diseases. For example, it can be a part of ventricular remodeling in consequence of ischemic heart disease or a component of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the absence of ischemia.

Physiology

The ventricles are the chambers in the heart responsible for pumping blood either to the lungs (right ventricle)[3] or to the rest of the body (left ventricle).[4]

Healthy cardiac hypertrophy (physiologic hypertrophy or "athlete's heart") is the normal response to healthy exercise or pregnancy,[5] which results in an increase in the heart's muscle mass and pumping ability. Trained athletes have hearts that have left ventricular mass up to 60% greater than untrained subjects. Rowers, cyclists, and cross-country skiers tend to have the largest hearts, with an average left ventricular wall thickness of 1.3 centimeters, compared to 1.1 centimeters in average adults. Heart wall thickness can be measured by ultrasound; computed tomography is more accurate, though it is more expensive and has risks of exposure to radiation.

Unhealthy cardiac hypertrophy (pathological hypertrophy) is the response to stress or disease such as hypertension, heart muscle injury (myocardial infarction), heart failure or neurohormones. Valvular heart disease is another cause of pathological hypertrophy. It has also been suggested that the root cause of many heart ailments is cardiac hypertrophy, which in turn is caused by hypoxia due to atmospheric CO, particulate matter, and peroxyl acyl nitrates, which reduces ATP synthesis in cardiac mitochondria.[6][7] Pathological hypertrophy also leads to an increase in muscle mass, but the muscle does not increase its pumping ability, and instead accumulates myocardial scarring (collagen). In pathological hypertrophy, the heart can increase its mass by up to 150%.

In most situations, described above, the increase in ventricular wall thickness is a slow process. However, in some instances hypertrophy may be "dramatic and rapid." In the Burmese python, consumption of a large meal is associated with an increase in metabolic work by a factor of seven and a 40% increase in ventricular mass within 48 hours, both of which return to normal within 28 days.[8]

Aerobic training results in the heart being able to pump a larger volume of blood through an increase in the size of the ventricles. Anaerobic training results in the thickening of the myocardial wall to push blood through arteries compressed by muscular contraction.[9] This type of physiologic hypertrophy is reversible and non-pathological, increasing the heart's ability to circulate blood. Chronic hypertension causes pathological ventricular hypertrophy. This response enables the heart to maintain a normal stroke volume despite the increase in afterload. However, over time, pathological changes occur in the heart that lead to a functional degradation and heart failure.[10]

If the precipitating stress is volume overload (as through aerobic exercise, which increases blood return to the heart through the action of the skeletal-muscle pump), the ventricle responds by adding new sarcomeres in-series with existing sarcomeres (i.e., the sarcomeres lengthen rather than thicken). This results in ventricular dilation while maintaining normal sarcomere lengths - the heart can expand to receive a greater volume of blood. The wall thickness normally increases in proportion to the increase in chamber radius. This type of hypertrophy is termed eccentric hypertrophy.[11]

All muscles (including the heart) work more efficiently and safely when they are having an optimal preload. Hence the physiological processes of hypertrophy of aerobic exercise have been the ones that have been optimized by evolution.

In the case of chronic pressure overload (as through anaerobic exercise, which increases resistance to blood flow by compressing arteries), the chamber radius may not change; however, the wall thickness greatly increases as new sarcomeres are added in-parallel to existing sarcomeres. This is termed concentric hypertrophy.[11] This type of ventricle is capable of generating greater forces and higher pressures, while the increased wall thickness maintains normal wall stress. This type of ventricle becomes "stiff" (i.e., compliance is reduced), which can impair filling and lead to diastolic dysfunction.

The axis of the heart shifts toward the hypertrophied ventricle for two reasons:

- far more muscles exist on the hypertrophied side, which allows excess generation of electrical potentials on this side.

- more time is required for the depolarization to travel to the hypertrophied ventricle compared with the normal.

Mechanics of cardiac growth

As described in the previous section, it is believed that the eccentric hypertrophy is induced by volume-overload and that the concentric hypertrophy is induced by pressure-overload. Biomechanical approaches have been adopted to investigate the progression of cardiac hypertrophy for these two different types.[12][13]

In the framework of continuum mechanics, the volumetric growth is often modeled using a multiplicative decomposition of the deformation gradient into an elastic part and a growth part ,[14] where . For the generic orthotropic growth, the growth tensor can be represented as

,

where and are normally the orthonormal vectors of the microstructure, and is often referred as growth multipliers, which regulates the growth according to certain growth laws.

In eccentric growth, cardiomyocyte lengthens in the direction of the cell's long axis, . Therefore, the eccentric growth tensor can be expressed as

,

where is the identity tensor.

The concentric growth, on the other hand, induces parallel deposition of the sarcomeres. The growth of cardiomyocyte is in the transverse direction, and thus the concentric growth tensor is expressed as:

,

where is the vector perpendicular to tangent plane of the cardiac wall.

There are different hypothesis on the growth laws governing the growth multipliers and . Motivated by the observation that eccentric growth is induced by volume-overload, strain-driven growth laws are applied to the .[12][13] For the concentric growth, which is induced by pressure-overload, both stress-driven [12] and strain-driven [13] growth laws have been investigated and tested using computational finite element method. The biomechanical model based on continuum theories of growth can be used to predict the progression of the disease, and therefore can potentially help developing treatments to pathological hypertrophy.

See also

- Athletic heart syndrome

- Cardiac fibrosis

- Cardiology

- Cardiomegaly

- Cardiovascular disease

- Right ventricular hypertrophy

- ECG See diagnosis

References

- ↑ Ask the doctor: Left Ventricular Hypertrophy

- ↑ Right Ventricular Hypertrophy

- ↑ Right ventricle definition - Medical Dictionary definitions on MedTerms

- ↑ Left ventricle definition - Medical Dictionary definitions on MedTerms

- ↑ Mone SM, Sanders SP, Colan SD (August 1996). "Control mechanisms for physiological hypertrophy of pregnancy". Circulation. 94 (4): 667–72. doi:10.1161/01.cir.94.4.667. PMID 8772686.

- ↑ Acharya PVN; Irreparable DNA Damage by Industrial Pollutants in Pre-Mature Aging, Chemical Carcinogenesis and Cardiac Hypertrophy: Experiments and Theory; Israel Journal of Medical Sciences. Vol 13 (1977) p.441.

- ↑ Acharya PV; Irreparable DNA Damage by Industrial Pollutants in Pre-Mature Aging, Chemical Carcinogenesis and Cardiac Hypertrophy: Experiments and Theory; 1st International Meeting of Heads of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratories, April 1977; Jerusalem, Israel. Work conducted at Industrial Safety and Health Institute and Behavioral Cybernetics Laboratory, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

- ↑ Hill JA, Olson EN (March 2008). "Cardiac plasticity". N Engl J Med. 358 (13): 1370–80. doi:10.1056/NEJMra072139. PMID 18367740.

- ↑ McMurray, Robert (1998). Concepts in Fitness Programming. CRC. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-8493-8714-2.

- ↑ Mann DL, Bristow MR (May 2005). "Mechanisms and models in heart failure: the biomechanical model and beyond". Circulation. 111 (21): 2837–49. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.500546. PMID 15927992.

- 1 2 Hypertrophy

- 1 2 3 Göktepe, Serdar; Oscar John Abilez; Kevin Kit Parker; Ellen Kuhl (2010-08-07). "A multiscale model for eccentric and concentric cardiac growth through sarcomerogenesis". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 265 (3): 433–442. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.04.023. ISSN 0022-5193. PMID 20447409. Retrieved 2013-02-26.

- 1 2 3 Kerckhoffs, Roy C.P.; Jeffrey H. Omens; Andrew D. McCulloch (June 2012). "A single strain-based growth law predicts concentric and eccentric cardiac growth during pressure and volume overload". Mechanics Research Communications. 42: 40–50. doi:10.1016/j.mechrescom.2011.11.004. ISSN 0093-6413. Retrieved 2013-02-26.

- ↑ Ambrosi, D.; Ateshian, G.A.; Arruda, E.M.; Cowin, S.C.; Dumais, J.; Goriely, A.; Holzapfel, G.A.; Humphrey, J.D.; Kemkemer, R.; Kuhl, E.; Olberding, J.E.; Taber, L.A.; Garikipati, K. (April 2011). "Perspectives on biological growth and remodeling". Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids. 59 (4): 863–883. doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2010.12.011. ISSN 0022-5096. Retrieved 2013-02-26.