West Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana

| West Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

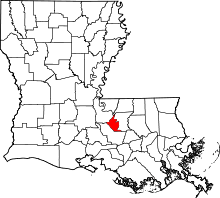

Location in the U.S. state of Louisiana | |

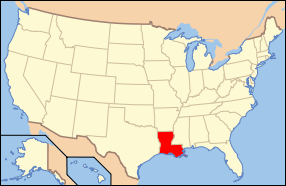

Louisiana's location in the U.S. | |

| Founded | March 31, 1807 |

| Named for | bâton rouge, French for red stick |

| Seat | Port Allen |

| Largest city | Port Allen |

| Area | |

| • Total | 204 sq mi (528 km2) |

| • Land | 192 sq mi (497 km2) |

| • Water | 11 sq mi (28 km2), 5.6% |

| Population | |

| • (2010) | 23,788 |

| • Density | 124/sq mi (48/km²) |

| Congressional districts | 2nd, 6th |

| Time zone | Central: UTC-6/-5 |

| Website |

www |

West Baton Rouge Parish (French: Paroisse de Bâton Rouge Ouest) is one of the sixty-four parishes in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2010 census, the population was 23,788.[1] The parish seat is Port Allen.[2] The parish was created in 1807.[3]

West Baton Rouge Parish is part of the Baton Rouge, LA Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The parish has a highly rated school system and is one of the few in Louisiana that has privatized school bus services. West Baton Rouge saw a very small percentage of growth after Hurricane Katrina with the latest estimate (July 2006) put about 864 extra residents into the parish.

History

Prehistory

The Medora Site, a Plaquemine culture mound site located adjacent to Bayou Bourbeaux on the flood plain of Manchac Point, a hair-pin bend of the Mississippi River in the southeast corner of the parish, was instrumental in defining the Plaquemine culture and period.[4] The site was excavated in the winter of 1939–40 by James A. Ford and George I. Quimby, for the Louisiana State Archaeological Survey, a joint project of Louisiana State University and the Work Projects Administration.[5]

Historic era

West Baton Rouge Parish was formed in 1807; it was named Baton Rouge Parish until 1812.

The Baton Rouge, Gross-Tete and Opelousas Railroad was chartered in 1853.[6] The company had an eastern terminus on the west bank of the Mississippi River across from Baton Rouge in what later became the City of Port Allen. A steam ferry boat, the Sunny South, made three trips a day to connect the railroad to Baton Rouge. The railroad ran westward into neighboring Iberville Parish passing the village of Rosedale. After reaching Bayou Grosse-Tete near the village of Grosse Tete, the line turned to the northwest and ran to Livonia in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, a total distance of twenty-six miles. The roadbed westward from Livonia to the Atchafalaya River had been prepared by 1861.

Civil War

The advent of the Civil War prevented the railroad from getting the necessary rails to complete the line. The tracks to Opelousas were never built.

After Louisiana seceded, two companies of militia were organized in West Baton Rouge, the Delta Rifles, headed by Captain Favrot and the Tirailleurs of Brusly Landing, a French-speaking company of creoles headed by Captain Williams. The two West Baton Rouge companies were included in the 4th Louisiana Regiment, commanded by Colonel Robert J. Barrow, assisted by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Watkins Allen. The regiment participated in the Battle of Shiloh, the Battle of Baton Rouge and other actions.[7]

The railroad operated up until May 1862 carrying sugar cane, cotton, and Confederate troops, including the Delta Rifles headed by Captain H. M. Favrot.[8] When Union force occupied Baton Rouge in May 1862, all rolling stock was sent to the extreme western end of the railroad for safety where it remained for the duration of the war.[9] Mr. J. V. Duralde was the president of the company during the Civil War period.

Many Baton Rouge residents took refuge in West Baton Rouge Parish during the Union occupation of Baton Rouge in 1862.[10] Sarah Morgan saw the CSS Arkansas, a Confederate ram, tied to the bank below the levee in West Baton Rouge Parish prior to the Battle of Baton Rouge. Morgan observed the Battle of Baton Rouge from West Baton Rouge Parish.[10]

The CSS Arkansas suffered the failure of the port engine while proceeding upriver during the battle to get into position to attack the USS Essex. This caused it to veer into the West Baton Rouge bank about 600 feet south of mile marker 223 where it ran hard aground. The crew of the CSS Arkansas then set the vessel afire and scuttled it to avoid it falling into enemy hands.[11]

The defeated Union army under the command of Major General Nathaniel P. Banks passed through West Baton Rouge Parish on Rosedale Road on its return to New Orleans in May 1864 after the failure of the Red River Campaign.[12]

During the final weeks of the American Civil War, heavy rains created crevasses in the West Baton Rouge Parish levee, and flood waters overflowed the area, bringing a temporary halt to military skirmishes.[13] At this time West Baton Rouge as well as Iberville and lower Pointe Coupee parishes were reportedly "infested with unorganized bodies of jayhawkers." They were guilty of many crimes against the people of the area as well as firing on the laborers repairing the levee and upon Federal steamboats in the river. Federal officials and Confederate authorities deplored the lawless actions of these men and both parties desired to break up jayhawking. There was even a truce between Union and Confederate forces until the problem of the jayhawkers was resolved.[13]

Post Civil War period

The American Civil War devastated the sugar industry that had flourished in the southern part of Louisiana, including West Baton Rouge Parish, prior to the war. The control of the Mississippi River by the Union prevented the sugar crop from going to market, Horses and mules were seized by the Union forces, and crops were left unharvested in the fields, so the sugar industry was bankrupt at the end of the Civil War. Many sugar plantations ware taken over by northern interests.[14] West Baton Rouge Parish was no exception. The conveyance records on file with the Clerk-of-Court of West Baton Rouge Parish show that many plantation properties were sold at sheriff's sale to satisfy debts in the years immediately after the end of the Civil War.

The Baton Rouge, Grosse Tete, and Opelousas Railroad resumed operation after the end of hostilities, but found the economy adverse, because of the devastation in agriculture. Moreover, its sixty-nine slaves had been emancipated and had to be replaced with hired labor. Furthermore, the "Great Crevasse", which occurred in the north end of West Baton Rouge Parish in 1867, caused flooding that greatly damaged the track in a low section about six miles west of the Mississippi River. The now unprofitable rail company eventually ceased operations in 1883.[9] The assets of the railroad were acquired by the Louisiana Central Railroad and operated until 1902.

The Texas and Pacific Railway was chartered by the United States Congress in 1871 to build a southern transcontinental railroad. The route started in Westwego (on the west bank of the Mississippi near New Orleans) and ran northwestward on the west bank of the Mississippi and on to Alexandria, Shreveport, thence westward to Fort Worth, and El Paso where it joined the Southern Pacific Railroad. The route passes though the southwestern part of West Baton Rouge Parish. A junction was established in the southern part of the parish from which a spur line ran twelve miles northward to the west bank of the Mississippi river across from Baton Rouge at a location which was already called "Port Allen". The junction was called "Baton Rouge Junction".[15] The town of Addis grew up around Baton Rouge Junction. The Texas and Pacific acquired additional right-of-way in 1899 to extend the spur from Port Allen to New Roads, Louisiana and beyond to Alexandria, Louisiana.[16]

Twentieth century

A crevasse in northern Point Coupeé Parish near Torras in May 1912 caused flooding that spread into northern West Baton Rouge Parish and southward to Addis west of the Texas and Pacific Railroad.[17]

The Texas and Pacific was merged into the Missouri Pacific Railroad in 1976. A further merger of the Missouri Pacific and the Union Pacific occurred in 1997, making the Texas and Pacific part of the Union Pacific Railroad.

The Southern Pacific Railroad built a spur line from Lafayette, Louisiana to Anchorage in West Baton Rouge very early in the twentieth century. The line ran in a straight line and is notable for crossing the Atchafalaya Basin. The line was never financially successful and was abandoned in the 1920s. Southern Pacific Road occupies the former right-of-way of a small portion of the line.

Starting in 1906, the Missouri Pacific Railroad operated the George H. Walker, a rail ferry, called a "transfer boat", from Anchorage (immediately north of the Sunrise Community) in West Baton Rouge Parish across the Mississippi River to Baton Rouge in East Baton Rouge Parish.[18] The transfer boat was steam-powered and equipped with rails on its deck that allowed passenger and freight railcars to be rolled on and off. It ceased operation September 2, 1947 after the construction of the Huey P. Long Bridge, which included a railway, made its continued operation unnecessary.

West Baton Rouge Parish was the location of Prisoner of War Sub-Camp 7 from 1943 until mid-1946. The camp housed German prisoners who were deployed as plantation labor. The camp was located on West Baton Rouge Parish property fronting on Sixth Street in Port Allen.[19]

The Cinclare Sugar Mill Historic District is located in West Baton Rouge Parish near Brusly.[20]

Law and government

West Baton Rouge Parish is governed by a parish council.

West Baton Rouge Parish has three incorporated areas (Port Allen, Brusly, and Addis) with local police departments. The West Baton Rouge Sheriff's Department is responsible for law enforcement in all of the unincorporated areas.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the parish has a total area of 204 square miles (530 km2), of which 192 square miles (500 km2) is land and 11 square miles (28 km2) (5.6%) is water.[21] It is the second-smallest parish in Louisiana by land area and smallest by total area.

The southwestern portion of the parish is uninhabited timberland. The most prominent geographic feature is the Mississippi River which forms the east border of the parish. Levees along the river protect the parish from flooding by the Mississippi River in times of high water.

The parish is contained within the Two Rivers Region of the Atchafalaya National Heritage Area.[22]

Adjacent parishes

- West Feliciana Parish (north)

- East Baton Rouge Parish (east)

- East Feliciana Parish (northeast)

- Iberville Parish (southwest)

- Pointe Coupee Parish (northwest)

Transportation

Major highways

Interstate 10

Interstate 10 U.S. Highway 190

U.S. Highway 190 Louisiana Highway 1

Louisiana Highway 1-

Louisiana Highway 76

Louisiana Highway 76 -

Louisiana Highway 327

Louisiana Highway 327 -

Louisiana Highway 411

Louisiana Highway 411 -

Louisiana Highway 413

Louisiana Highway 413 -

Louisiana Highway 415

Louisiana Highway 415 -

Louisiana Highway 620

Louisiana Highway 620 -

Louisiana Highway 982

Louisiana Highway 982 -

Louisiana Highway 983

Louisiana Highway 983 -

Louisiana Highway 984

Louisiana Highway 984 -

Louisiana Highway 985

Louisiana Highway 985 -

Louisiana Highway 986

Louisiana Highway 986 -

Louisiana Highway 987-1

Louisiana Highway 987-1 -

Louisiana Highway 987-2

Louisiana Highway 987-2 -

Louisiana Highway 987-3

Louisiana Highway 987-3 -

Louisiana Highway 988

Louisiana Highway 988 -

Louisiana Highway 989-1

Louisiana Highway 989-1 -

Louisiana Highway 989-2

Louisiana Highway 989-2 -

Louisiana Highway 990

Louisiana Highway 990 -

Louisiana Highway 1145

Louisiana Highway 1145 -

Louisiana Highway 1148

Louisiana Highway 1148 -

Louisiana Highway 3091

-

Louisiana Highway 3237

Louisiana Highway 3237

West Baton Rouge Parish is connected to East Baton Rouge Parish by the Huey P. Long Bridge (U.S. Highway 190) and the Horace Wilkinson Bridge (Interstate 10).

Rail

West Baton Rouge is served by the Kansas City Southern Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 1,463 | — | |

| 1820 | 2,335 | 59.6% | |

| 1830 | 3,084 | 32.1% | |

| 1840 | 4,638 | 50.4% | |

| 1850 | 6,270 | 35.2% | |

| 1860 | 7,312 | 16.6% | |

| 1870 | 5,114 | −30.1% | |

| 1880 | 7,667 | 49.9% | |

| 1890 | 8,363 | 9.1% | |

| 1900 | 10,285 | 23.0% | |

| 1910 | 12,636 | 22.9% | |

| 1920 | 11,092 | −12.2% | |

| 1930 | 9,716 | −12.4% | |

| 1940 | 11,263 | 15.9% | |

| 1950 | 11,738 | 4.2% | |

| 1960 | 14,796 | 26.1% | |

| 1970 | 16,864 | 14.0% | |

| 1980 | 19,086 | 13.2% | |

| 1990 | 19,419 | 1.7% | |

| 2000 | 21,601 | 11.2% | |

| 2010 | 23,788 | 10.1% | |

| Est. 2015 | 25,490 | [23] | 7.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[24] 1790-1960[25] 1900-1990[26] 1990-2000[27] 2010-2013[1] | |||

As of the census of 2000, there were 21,601 people, 7,663 households, and 5,739 families residing in the parish. The population density was 113 people per square mile (44/km²). There were 8,370 housing units at an average density of 44 per square mile (17/km²). The racial makeup of the parish was 62.78% White, 35.49% Black or African American, 0.20% Native American, 0.19% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.53% from other races, and 0.79% from two or more races. 1.45% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 8,386 households out of which 37.60% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.50% were married couples living together, 18.20% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.10% were non-families. 21.50% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.10% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.74 and the average family size was 3.20.

In the parish the population was spread out with 28.10% under the age of 18, 9.90% from 18 to 24, 30.60% from 25 to 44, 21.70% from 45 to 64, and 9.70% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females there were 96.60 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.40 males.

The median income for a household in the parish was $47,298 and the per capita income was $22.101. Males had a median income of $35,618 versus $22,960 for females. About 13.20% of families and 16.00% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.20% of those under age 18 and 13.10% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

West Baton Rouge's location on the Mississippi River plus railroad transportation has made it attractive to heavy industry. Notable industry includes Placid Refining Company near Port Allen and Dow Chemical Company and ShinTech near Addis.

The docks and other property of the Port of Greater Baton Rouge are located in West Baton Rouge Parish.[28]

Interstate Highway 10 makes West Baton Rouge attractive as a distribution center. A number of warehouses have been built near I-10. Many trucking firms have located near the Huey P. Long Bridge.

Education

West Baton Rouge Parish School Board operates area public schools.

Holy Family School is a local private Catholic school for grades pre-K through Eight.[29]

Museums and libraries

The West Baton Rouge Museum, located in Port Allen, maintains historical information on West Baton Rouge Parish.[30] The Town of Addis operates a museum that keeps historical information about the Town of Addis.[31]

The Parish of West Baton Rouge maintains a library in Port Allen.[32]

Media

West Baton Rouge Parish is served by two weekly newspapers. The West Side Journal, published every Thursday, provides hard news and is the official journal of the parish. The Riverside Reader, published every Monday, focuses on items of historical interest and human interest stories.

Communities

City

Towns

Census-designated place

Unincorporated communities

Notable residents

- Henry Watkins Allen

- Slim Harpo

- John Hill

- Edmond Jordan, represents District 29 (West and East Baton Rouge parishes) in the Louisiana House of Representatives

- Raful Neal

- Major Thibaut, represents West Baton Rouge Parish in the Louisiana House of Representatives

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in West Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana

- Louisiana in the Civil War

References

- 1 2 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "West Baton Rouge Parish". Center for Cultural and Eco-Tourism. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- ↑ "LOUISIANA COMPREHENSIVE STATEWIDE HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN-September 28, 2001". Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- ↑ Quimby, George Irving (1951). "THE MEDORA SITE of WEST BATON ROUGE PARISH, LOUISIANA". ANTHROPOLOGICAL SERIES, FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, VOLUME XXIV, NUMBER 2. Chicago Field Museum Press.

- ↑ "Baton Rouge, Gross-Tete and Opelousas Railroad". Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ↑ Richey, Thomas H. Tiralleurs: A History of the 4th Louisiana and the Acadians of Company H. New York: Writers Advantage, 2003. ISBN 0-595-27258-4.

- ↑ "Delta Rifles". Retrieved 2011-11-09.

- 1 2 Estaville Jr., Lawrence E. (1977). "A small contribution: Louisiana's short rural railroads in the Civil War". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 18.

- 1 2 Charles East, ed. (1991). Sarah Morgan: The Civil War Diary of a Southern Woman. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- ↑ Foote, Shelby (1986). The Civil War: Fort Sumpter to Perryville. New York: Vintage Books. p. 579.

- ↑ Rosedale Road. Louisiana Historical Markers.

- 1 2 Winters, John D. (1963). The Civil War in Louisiana. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 411–413. ISBN 0-8071-0834-0.

- ↑ Roland, Charles P. (1957). Louisiana Sugar Plantations During the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2221-1.

- ↑ Baedeker, Karl, ed. The United States with an Excursion into Mexico: A Handbook for Travelers, 1893: p. 468 (Reprint by Da Capo Press, New York, 1971.)

- ↑ Conveyance Records of the West Baton Rouge Clerk of Court.

- ↑ The great flood of 1912. The Riverside Reader, Port Allen, LA, Monday, April 2, 3012.

- ↑ Sunrise historical marker

- ↑ Écoutez 2011;XLIII(3):4

- ↑ "Cinclare Sugar Mill Historic District". National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ Between Two Rivers Region.

- ↑ "County Totals Dataset: Population, Population Change and Estimated Components of Population Change: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ Port of Greater Baton Rouge

- ↑ "Holy Family School About Us". Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ↑ "West Baton Rouge Museum". Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ↑ Town of Addis Museum

- ↑ West Baton Rouge Parish Library

External links

- West Baton Rouge Parish Portal

- West Baton Rouge Parish Government - Official site.

- West Baton Rouge Parish Chamber of Commerce.

- Explore the History and Culture of Southeastern Louisiana, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- West Baton Rouge Parish Sheriff's Office

Geology

- Heinrich, P. V., and W. J. Autin, 2000, Baton Rouge 30 x 60 minute geologic quadrangle. Louisiana Geological Survey, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Additional reading

- Phillips, Faye, editor. The History of West Baton Rouge Parish. St. Louis: Reedy Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1-935806-38-7.

|

Pointe Coupee Parish | West Feliciana Parish | East Feliciana Parish |  |

| |

East Baton Rouge Parish | |||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Iberville Parish |

Coordinates: 30°28′N 91°19′W / 30.46°N 91.31°W