Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was the leading militant organisation campaigning for Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, 1903–1917. Its membership and policies were tightly controlled by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia (although Sylvia broke away). It was best known for hunger strikes (and forced feeding), for breaking windows in prominent buildings, and for night-time arson of unoccupied houses and churches.

Formation

The Women's Social Political Union was founded at the Pankhurst family home in Manchester on 10 October 1903 by six women, including Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, who soon emerged as the group's leaders. The Women's Social Political Union had split from the non-militant National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, disappointed at the lack of success its tactics of persuading politicians through meetings had found.[1]

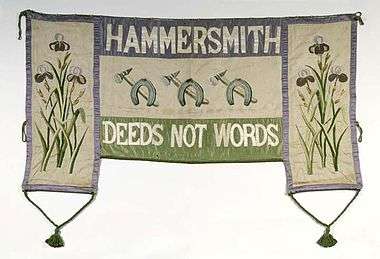

The founders decided to form a women-only organisation, which would campaign for social reforms, largely in conjunction with the Independent Labour Party. They would also campaign for an extension of women's suffrage, believing that this was central to sexual equality. To illustrate their more militant stance, they adopted the slogan "Deeds, not words".[1] By 1913, the WSPU appointed the fiercely militant feminist Nora Dacre Fox (later known as Norah Elam) as General Secretary. Dacre Fox operated as a highly effective propagandist delivering rousing speeches at the WSPU weekly meetings and writing many of Christabel Pankhurst's speeches.[2]

Early campaigning

In 1905, the group convinced the Member of Parliament Bamford Slack to introduce a women's suffrage bill, which was ultimately talked out, but the publicity spurred rapid expansion of the group. The WSPU changed tactics following the failure of the bill; they focused on attacking whichever political party was in government and refused to support any legislation which did not include enfranchisement for women. This translated into abandoning their initial commitment to also supporting immediate social reforms.[1]

In 1906, the group began a series of demonstrations and lobbies of Parliament, leading to the arrest and imprisonment of growing numbers of their members. An attempt to achieve equal franchise gained national attention when an envoy of three hundred women, representing over 125,000 suffragettes argued for women's suffrage with the Prime Minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman. The Prime Minister agreed with their argument but "was obliged to do nothing at all about it" and so urged the women to "go on pestering" and to exercise "the virtue of patience".[3] Some of the women Campbell-Bannerman advised to be patient had been working for women's rights for as many as fifty years: his advice to "go on pestering" would prove quite unwise. His thoughtless words infuriated the protesters and "by those foolish words the militant movement became irrevocably established, and the stage of revolt began".[3] Commenting on the phenomenon, Charles Hands, writing in the Daily Mail, for the first time described the WSPU's members as suffragettes. In 1907 the organisation held the first of several of their "Women's Parliaments".[1]

The Labour Party then voted to support universal suffrage. This split them from the WSPU, which had always accepted the property qualifications which already applied to women's participation in local elections. Under Christabel's direction, the group began to more explicitly organise exclusively among middle class women, and stated their opposition to all political parties. This led a small group of prominent members to leave and form the Women's Freedom League.[1]

Campaigning develops

Immediately following the WSPU/WFL split, in autumn 1907, Frederick and Emmeline Pethick Lawrence founded the WSPU's own newspaper, Votes for Women. The Pethick Lawrences, who were part of the leadership of the WSPU until 1912, edited the newspaper and supported it financially in the early years.

In 1908 the WSPU adopted purple, white, and green as its official colours. These colours were chosen by Emmeline Pethick Lawrence because "Purple...stands for the royal blood that flows in the veins of every suffragette...white stands for purity in private and public life...green is the colour of hope and the emblem of spring".[4] June 1908 saw the first major public use of these colours when the WSPU held a 300,000-strong "Women's Sunday" rally in Hyde Park.

In February 1907 the WSPU founded the Woman's Press, which oversaw publishing and propaganda for the organisation, and marketed a range of products from 1908 featuring the WSPU's name or colours. The woman's Press in London and WSPU chains throughout the UK operated stores selling WSPU products.[5] Until January 1911, the WSPU's official anthem was "The Women's Marseillaise",[6] a setting of words by Florence Macaulay to the tune of "La Marseillaise".[7] In that month the anthem was changed to "The March of the Women",[6] newly composed by Ethel Smyth with words by Cicely Hamilton.[8]

Campaigning becomes more militant

In opposition to the continuing and repeated imprisonment of many of their members, the WSPU introduced the prison hunger strike to Britain, and the authorities' policy of force feeding won the suffragettes great sympathy from the public. The government later passed the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913 (more commonly known as the "Cat and Mouse Act"), which allowed the release of suffragettes who were close to death due to malnourishment. Officers, however, could re-imprison them again once they were healthy. This was an attempt to avoid force-feeding.[1] In response, the WSPU organised an all-women security team known as the Bodyguard, trained by Edith Margaret Garrud and led by Gertrude Harding, whose role was to protect fugitive suffragettes from re-imprisonment.

A new suffrage bill was introduced in 1910, but growing impatient, the WSPU launched a heightened campaign of protest in 1912 on the basis of targeting property and avoiding violence against any person. Initially this involved smashing shop windows, but ultimately escalated to burning stately homes and bombing public buildings including Westminster Abbey. It also famously led to the death of Emily Davison as she was trampled by the King's horse, Anmer, (over which she was attempting to drape a suffragette banner) at the Epsom Derby in 1913.

Included in the many militant acts performed were the night-time arson of unoccupied houses (including that of Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George) and churches. Suffragettes smashed windows of upscale shops and government offices. They cut telephone lines, spit at police and politicians, cut or burned pro-suffrage slogans into stadium turf,[9] sent letter bombs, destroyed greenhouses at Kew gardens, chained themselves to railings and blew up houses. A doctor was attacked with a rhino whip, and in one case suffragettes rushed the House of Commons. On 18 July 1912, Mary Leigh threw a hatchet at Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith.

On the evening of 9 March 1914, about 40 militant suffragettes, including members of the Bodyguard team, brawled with several squads of police constables who were attempting to re-arrest Emmeline Pankhurst during a pro-suffrage rally at St. Andrew's Hall in Glasgow. The following day, suffragette Mary Richardson (known as one of the most militant activists, also called "Slasher" Richardson) walked into the National Gallery and attacked Diego Velázquez's Rokeby Venus with a meat cleaver. In 1913 suffragette militancy caused £54,000 worth of damage, £36,000 of which occurred in April alone.

The organisation also suffered divisions. The editors of Votes for Women, Frederick and Emmeline Pethick Lawrence, were expelled in 1912, later founding the United Suffragists. This caused the WSPU to launch a new journal, The Suffragette, edited by Christabel Pankhurst. The East London Federation of mostly working class women and led by Sylvia Pankhurst was expelled in 1914.[1]

WSPU during the First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Christabel Pankhurst was living in Paris, in order to run the organisation without fear of arrest. Her autocratic control enabled her, over the objections of Kitty Marion and others,[9] to declare soon after war broke out that the WSPU should abandon its campaigns in favour of a nationalistic stance, supporting the British government in the war. The WSPU stopped publishing The Suffragette, and in April 1915 it launched a new journal, Britannia. While the majority of WSPU members supported the war, a small number formed the Suffragettes of the Women's Social Political Union (SWSPU) and the Independent Women's Social and Political Union (IWSPU). The WSPU faded from public attention and was dissolved in 1917, with Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst founding the Women's Party.[1]

Impact

The militant campaign had some positive effects in terms of attracting enormous publicity, and forcing the moderates to better organize themselves. [10]

Notable members of WSPU

- Janie Allan

- Barbara Ayrton

- Rosa May Billinghurst

- Teresa Billington-Greig

- Elsie Bowerman

- Helen Cruickshank

- Charlotte Despard

- Emily Davison

- Flora Drummond

- Sophia Duleep Singh

- Norah Elam

- Louisa Garrett Anderson

- Edith Margaret Garrud

- Mary Gawthorpe

- Nellie Hall

- Beatrice Harraden

- Edith How-Martyn

- Elsie Howey

- Ellen Isabel Jones

- Annie Kenney

- Aeta Adelaide Lamb

- Mary Leigh

- Lilian Lenton

- Constance Lytton

- Mary Macarthur

- Margaret Mackworth, 2nd Viscountess Rhondda

- Christabel Marshall

- Kitty Marion

- Dora Marsden

- Dora Montefiore

- Flora Murray

- Margaret Nevinson

- Edith New

- Adela Pankhurst

- Christabel Pankhurst

- Emmeline Pankhurst

- Sylvia Pankhurst

- Frances Parker

- Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

- Mary Richardson

- Edith Rigby

- Rona Robinson

- Mary Russell, Duchess of Bedford

- Dame Ethel Mary Smyth

- Harriet Shaw Weaver

- Evelyn Sharp

- Dora Thewlis

- Olive Wharry

- Rose Emma Lamartine Yates

See also

- Feminism in the United Kingdom

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- List of women's rights organizations

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Women's suffrage organizations

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mary Davis, Sylvia Pankhurst (Pluto Press, 1999) ISBN 0-7453-1518-6

- ↑ McPherson, Angela; McPherson, Susan (2011). Mosley's Old Suffragette – A Biography of Nora Elam. ISBN 978-1-4466-9967-6.

- 1 2 Ray Strachey, The Cause: A Short History of the Women's Movement in Great Britain p.301

- ↑ Quotation from the journal Votes for Women in 1908 cited by David Fairhall, Common Ground, Tauris, 2006 p 31.

- ↑ John Mercer, "Shopping for Suffrage: The Campaign Shops of the Women's Social and Political Union", Women's History Review, 2009, doi:10.1080/09612020902771053

- 1 2 Purvis, June (2002). Emmeline Pankhurst: a Biography. London: Routledge. p. 157. ISBN 0-415-23978-8.

- ↑ Crawford, Elizabeth (2001). The Women's Suffrage Movement: a Reference Guide, 1866–1928. London: Routledge. p. 645. ISBN 0-415-23926-5.

- ↑ Bennett, Jory (1987). Crichton, Ronald, ed. The Memoirs of Ethel Smyth: Abridged and Introduced by Ronald Crichton, with a list of works by Jory Bennett. Harmondsworth: Viking. p. 378. ISBN 0-670-80655-2.

- 1 2 Spartacus: Kitty Marion

- ↑ Bob Whitfield, The Extension of the Franchise, 1832–1931 (2001) p 160

Further reading

- Bartley, Paula. Emmeline Pankhurst (2002)

- Bearman, C. J. "An examination of suffragette violence." English Historical Review (2005) 120#486 pp: 365–397.

- Crawford, Elizabeth. The Women's Suffrage Movement: a Reference Guide, 1866–1928 (2001)

- Davis, Mary. Sylvia Pankhurst (Pluto Press, 1999)

- Harrison, Shirley. Sylvia Pankhurst: a crusading life, 1882–1960 (Aurum Press, 2003)

- Holton, Sandra Stanley. "In sorrowful wrath: suffrage militancy and the romantic feminism of Emmeline Pankhurst." in Harold Smith, ed. British feminism in the twentieth century (1990) pp: 7–24.

- Loades, David, ed. Reader's guide to British history. (Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2003). 2:999–1000, historiography

- Marcus, Jane. Suffrage and the Pankhursts (1987)

- Purvis, June. Emmeline Pankhurst: a Biography (2002)

- Purvis, June. "Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928), Suffragette Leader and Single Parent in Edwardian Britain." Women's History Review (2011) 20#1 pp: 87–108.

- Romero, Patricia W. E. Sylvia Pankhurst: Portrait of a radical (Yale U.P., 1987)

- Smith, Harold L. The British women's suffrage campaign, 1866–1928 (2nd ed. 2007)

- Strachey, Ray. The Cause: A Short History of the Women's Movement in Great Britain

- Winslow, Barbara. Sylvia Pankhurst: sexual politics and political activism (1996)

External links

- Papers, 1911–1913.

- Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.