Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park

| Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park | |

|---|---|

|

Native name | |

|

This petroglyph was created prior to the arrival of the horse. It shows a warrior carrying a body shield. | |

| Location |

County of Warner No. 5, |

| Coordinates | 49°4′55″N 111°37′1″W / 49.08194°N 111.61694°WCoordinates: 49°4′55″N 111°37′1″W / 49.08194°N 111.61694°W |

| Area | 17.8 square kilometres (6.9 sq mi) |

| Founded | January 8, 1957 |

| Governing body | Alberta Environment and Parks |

| Official name: Áísínai’pi National Historic Site of Canada | |

| Designated | March 2005 |

| Official name: Writing-on-Stone, Glyphs | |

| Type | Provincial historic resource |

| Designated | 1981[1] |

| Reference no. | 4665-0060 |

IUCN Category III (Natural Monument) | |

| Designated | 1977 |

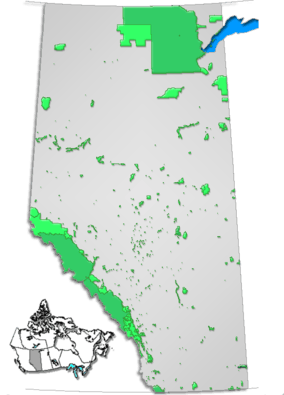

Location of Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park in Alberta | |

Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park is located about 100 kilometres southeast of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada, or 44 kilometres east of the community of Milk River, and straddles the Milk River itself. It is one of the largest areas of protected prairie in the Alberta park system, and serves as both a nature preserve and protection for a large number of aboriginal rock carvings and paintings. The park is important and sacred to the Blackfoot and many other aboriginal tribes. The park has been nominated by Parks Canada and the Government of Canada as a World Heritage Site. Its UNESCO application was filed under the name Áísínai’pi which is Niitsítapi (Blackfoot) meaning "it is pictured / written".[2] The provincial park is synonymous with the Áísínai’pi National Historic Site of Canada.[3]

Resources

Writing-on-Stone Park contains the greatest concentration of rock art on the North American Great Plains. There are over 50 petroglyph sites and thousands of works. The park also showcases a North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) outpost reconstructed on its original site. It was rebuilt since the original outpost was burned down by persons unknown.

Nature

The park comprises 17.80 square kilometres (4400 acres) of coulee and prairie habitat, and boasts a diverse variety of birds and animals.

Bird species include prairie falcon, great horned owl, short-eared owl, American kestrel, cliff swallow and the introduced ring-necked pheasant and grey partridge.

The prairie surrounding the park is a habitat for pronghorn antelope, and other species inhabiting the park include mule deer, northern pocket gophers, skunks, raccoons, yellow-bellied marmots, and bobcat. Tiger salamanders, boreal chorus frogs and leopard frogs, and plains spadefoot toads represent the amphibians, and garter snakes, bull snakes and prairie rattlesnakes can be found.

The coulee environment is optimal for tree species such as balsam poplar and narrow leaf cottonwood. Peachleaf willow and plains cottonwood are also found here. A large number of shrubs grow here, including chokecherry, juniper, saskatoon, sandbar willow, and two varieties of wild rose. Some of the most northern species of cactus, including Opuntia (prickly pear) and Pediocactus (pincushion) are found in the park as well.

Prehistory

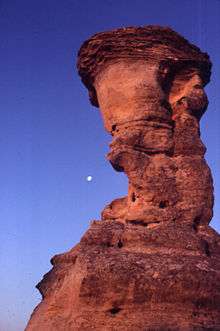

The location where the park now sits was, 85 million years ago, the coastal shelf of a large inland sea. Sand deposited in the Late Cretaceous Period compacted over time and became sandstone. With the melting of the ice sheets at the end of the last Ice Age, water, ice and wind eroded the sandstone to produce the hoodoos and cliffs that are part of the park today.

History

There is evidence that the Milk River Valley was inhabited by native people as long ago as 9000 years. Native tribes such as the Blackfoot probably created much of the rock carvings (petroglyphs) and paintings (pictographs). Other native groups such as the Shoshone also travelled through the valley and may have also created some of the art. These carvings and paintings tell not only of the lives and journeys of those who created them, but also of the spirits they found here. The towering cliffs and hoodoos had a powerful impact on the native visitors, who believed these were the homes of powerful spirits. The shelter of the coulees and the abundance of game and berries made the area that is now the park an excellent location for these nomadic people to stop on their seasonal migrations. While the greatest use of the area was made by those in transit, there is some evidence, including tipi rings and a medicine wheel, that there was some permanent settlement here.

Beginning about 1730, large numbers of horses, metal goods, and guns began to appear on the Western plains. This signified not only a change in the native lifestyle, but a change in the content of the rock art. Pictures of hunters on horseback, and warriors without body shields began to be created.

In 1887 a North-West Mounted Police (the precursor to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police) camp was set up at Writing-On-Stone to attempt to curtail cross-border whiskey smuggling, which was devastating the native population, and to put a stop to native horse-raiding parties. But in fact neither problem ever became serious at this outpost, and the NWMP spent most of their time fighting summer grass fires, herding stray American cattle back across the border, and riding hundreds of uneventful kilometres on border patrol. In the period immediately preceding World War I, settlers began to arrive in the area, which helped to alleviate some of the boredom and isolation the NWMP officers faced. In 1918, the outpost was closed, as Canadian authorities felt little possibility of criminal activity along the border, and shortly thereafter, the outpost fell victim to arson by persons unknown.

The park was created in 1957 and was designated an archaeological preserve in 1977. As part of the NWMP centennial celebrations, the outpost was reconstructed between 1973 and 1975, and is now one of the attractions in the park. Archaeologists from the Alberta Provincial Parks Department surveyed and catalogued numerous petroglyph and pictograph sites within the park in 1973. In 1981, a portion of the park was named a Provincial Historic Resource to protect this rock art from increasing impact from vandalism and graffiti. The most sensitive areas are now set aside in areas designated for guided tours only. In 1977, the park preserved the archaeology of the pictographs and petroglyphs. This protection makes the park one of the largest concentrations of rock art in the North American Plains.[4] In 2004 Parks Canada added the park to Canada's tentative list of possible world heritage sites. The application indicated that the Blackfoot people would also like the Kátoyissiksi or Sweetgrass Hills of Montana included as part of the world heritage site. In March 2005, the park was designated a National Historic Site. On June 20, 2007, the park's new visitor centre, with views of the valley from the north rim, was officially opened.

See also

References

- ↑ Alberta Culture. "Writing-on-Stone, Glyphs". Alberta Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ↑ http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/1935/

- ↑ http://www.pc.gc.ca/docs/r/ab/sites/writing-on-stone_E.asp

- ↑ Writing-On-Stone Provincial Park, Park Research and Management Retrieved August 3, 2015

Further reading

- Bouchet-Bert, Lus. "From Spiritual and Biographic to Boundary-Marking Deterrent Art: A Reinterpretation of Writing-on-Stone". Plains Anthropologist 44.167 (1999): 27-46.

External links

- Alberta: How the West was Young - Archaeology and Pre-contact - Writing-On-Stone

- Elders' Voices - Writing-On-Stone