Hatay Province

| Hatay Province Hatay ili | |

|---|---|

| Province of Turkey | |

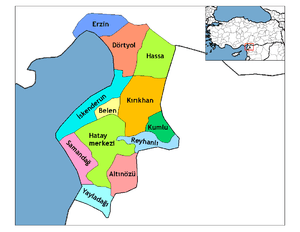

Location of Hatay Province in Turkey | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Region | Mediterranean |

| Subregion | Hatay |

| Government | |

| • Electoral district | Hatay |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5,831.36 km2 (2,251.50 sq mi) |

| Population (2010-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 1,480,571 |

| • Density | 250/km2 (660/sq mi) |

| Area code(s) | 0326 |

| Vehicle registration | 31 |

Hatay Province (Turkish: Hatay ili, pronounced [ˈhataj]) is a province in southern Turkey, on the Mediterranean coast. The administrative capital is Antakya (Antioch), and the other major city in the province is the port city of İskenderun (Alexandretta). It is bordered by Syria to the south and east and the Turkish provinces of Adana and Osmaniye to the north. The province is part of Çukurova (Cilicia), a geographical, economical and cultural region that covers the provinces of Mersin, Adana, Osmaniye, and Hatay. There are border crossing points with Syria in the district of Yayladağı and at Cilvegözü in the district of Reyhanlı. Sovereignty over the province remains disputed with neighbouring Syria, which claims that the province was separated from itself against the stipulations of the French Mandate of Syria in the years following Syria's independence from the Ottoman Empire after World War I. Although the two countries have remained generally peaceful in their dispute over the territory, Syria has never formally renounced its rights to it.

History

Antiquity

Settled since the early Bronze Age, Hatay was once part of the Akkadian Empire, then the Amorite Kingdom of Yamhad an Mitannis, then a succession of Hittites, the Neo-Hittite "Hattena" people that later gave the modern province of Hatay its name, then the Assyrians (except a brief occupation by Urartu) and Persians. The region was the center of the Hellenistic Seleucid empire, home to the four Greek cities of the Syrian tetrapolis (Antioch, Seleucia Pieria, Apamea, and Laodicea). From 64 BC onwards the city of Antioch became an important regional centre of the Roman Empire.

Islamic era

The area was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate in 638 and later it came under the control of the Ummayad and Abbasid Arab dynasties. From the 11th century onwards, the region was controlled by the Aleppo-based Hamdanids after a brief rule of Ikhshidids. In 969 the city of Antioch was recaptured by the Byzantine Empire. It was conquered by Philaretos Brachamios, a Byzantine general in 1078. He founded a principality from Antioch to Edessa. It was captured by Suleiman I, who was Sultan of Rum (ruler of Anatolian Seljuks), in 1084. It passed to Tutush I, Sultan of Aleppo (ruler of Syria Seljuks), in 1086. Seljuk rule lasted 14 years until Hatay's capture by the Crusaders in 1098, when it became the centre of the Principality of Antioch. Hatay was captured from the Crusaders by the Mameluks in 1268.

Sanjak of Alexandretta

By the time it was taken from the Mameluks by the Ottoman Sultan Selim I in 1516, Antakya was a medium-sized town on 2 km² of land between the Orontes River and Mount Habib Neccar. Under the Ottomans the area was known as the sanjak (or governorate) of Alexandretta. Gertrude Bell in her book Syria The Desert & the Sown published in 1907 wrote extensively about her travels across Syria including Antioch & Alexandretta and she noted the heavy mix between Turks and Arabs in the region at that time. A map published circa 1911 highlighted that the ethnic make up (Alexandretta) was majority Arab with smaller communities of Armenians and Turks.

Many consider that Alexandretta had been traditionally part of Syria. Maps as far back as 1764 confirm this.[2] During the First World War in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated most of Syria was occupied by the British forces. But when the armistice of Mudros was signed at the end of the war, Hatay was a still part of the Ottoman Empire. Nevertheless, after the armistice it was occupied by the British forces an operation which was never accepted by the Ottoman side. Later like the rest of Syria it was handed to France by the British Empire.

After World War I and the Turkish War of Independence, the Ottoman Empire was disbanded and the modern Republic of Turkey was created, and Alexandretta was not part of the new republic, it was put within the French mandate of Syria after a signed agreement between the Allies and Turkey, the Treaty of Sèvres, which was neither ratified by the Ottoman parliament nor by the Turkish National Movement in Ankara.[3] The subsequent Treaty of Lausanne also put Alexandretta within Syria. The document detailing the boundary between Turkey and Syria around 1920 and subsequent years is presented in a report by the Official Geographer of The Bureau of Intelligence and Research of the US Department of State.[4] A French-Turkish treaty of 20 October 1921 rendered the Sanjak of Alexandretta autonomous, and remained so from 1921 to 1923. Out of 220,000 inhabitants in 1921, 87,000 were Turks.[5] Along with Turks the population of the Sanjak included: Arabs of various religious denominations (Sunni Muslims, Alawites, Greek Orthodox); Greek Catholics, Syriac-Maronites; Jews; Syriacs; Kurds; and Armenians. In 1923 Hatay was attached to the State of Aleppo, and in 1925 it was directly attached to the French mandate of Syria, still with special administrative status.

Despite this, a Turkish community remained in Alexandretta, and Mustafa Kemal said that Hatay had been a Turkish homeland for 4,000 years. This was due to the contested nationalist pseudoscientific Sun Language Theory prevalent in the 1930s in Turkey, which presumed that some ancient peoples of Anatolia and the Middle East such as the Sumerians and Hittites, hence the name Hatay, were related to the Turks. In truth, the Turks first appeared in Anatolia during the 11th century when the Seljuk Turks occupied the eastern province of the Abbasid Empire and captured Baghdad.[6] Resident Arabs organised under the banner of Arabism, and in 1930, Zaki Alarsuzi, a teacher and lawyer from Arsuz on the coast of Alexandretta published a newspaper called 'Arabism' in Antioch that was shut down by Turkish and French authorities.

The 1936 elections returned two MPs favouring the independence of Syria from France, and this prompted communal riots as well as passionate articles in the Turkish and Syrian press. This then became the subject of a complaint to the League of Nations by the Turkish government concerning alleged mistreatment of the Turkish populations. Atatürk demanded that Hatay become part of Turkey claiming that the majority of its inhabitants were Turks. The French High Commission estimated that the population of 220,000 inhabitants was made up of 39% Turks, 11% Armenians, 46% Arabs (28% Alawites, 10% Sunni, 8% Christians),[7] while the remaining 4% was made up of Circassians, Jews, and Kurds.[8] The sanjak was given autonomy in November 1937 in an arrangement brokered by the League. Under its new statute, the sanjak became 'distinct but not separated' from the French mandate of Syria on the diplomatic level, linked to both France and Turkey for defence matters.

Republic of Hatay

On 2 September 1938, as the Second World War loomed over Europe, the assembly proclaimed the Republic of Hatay. The Republic lasted for one year under joint French and Turkish military supervision. The name "Hatay" itself was proposed by Atatürk, and the government was under Turkish control. The president Tayfur Sökmen was a member of Turkish parliament elected in 1935 (representing Antalya), and the prime minister Abdurrahman Melek was also elected to the Turkish parliament (representing Gaziantep) in 1939 while still holding the prime-ministerial post.

Hatay Province of Turkey

On 29 June 1939, following a referendum, Hatay became a Turkish province. This referendum has been labelled both "phoney" and "rigged", and a way for the French to let Turks take over the area, hoping that they would turn on Hitler.[9][10] For the referendum, Turkey crossed tens of thousands of Turks into Alexandretta to vote.[11] These were Turks born in Hatay who were now living elsewhere in Turkey. In two government communiqués in 1937 and 1938, the Turkish government asked all local government authorities to make lists of their employees originally from Hatay. Those who listed were then sent to Hatay to register as citizens and vote.[12]

Syrian President Hashim al-Atassi resigned in protest at continued French intervention in Syrian affairs, maintaining that the French were obliged to refuse the annexation under the Franco-Syrian Treaty of Independence of 1936.

The Hassa district of Gaziantep, Dörtyol district of Adana and Erzin were then incorporated into Hatay. As a result of the annexation, a number of demographic changes occurred in Hatay. During the six months following the annexation, inhabitants over the age of 18 were given the right to choose between staying and becoming Turkish citizens, or emigrate to and acquire citizenship of French mandated Syria or Greater Lebanon. If choosing emigration, they were given 18 months to bring in their movable assets and establish themselves in their new states. Almost half of the Sunni Arabs left. Many Armenians also left and 1,068 Armenian families were relocated from the six Armenian villages of Musa Dagh to Beqaa Valley in Lebanon. Many of the Armenians had been prior victims to the Armenian Genocide committed by Turkey that had fled for their lives to the French Mandate of Syria. The total number of people who left for Syria is estimated at 50,000 including 22,000 Armenians, 10,000 Alawites, 10,000 Sunni Arabs and 5,000 Arab Christians.[13][14]

Turkish–Syrian dispute

In Ottoman times, Hatay was part of the Vilayet of Aleppo in Ottoman Syria. After World War I, Hatay (then known as Alexandretta) became part of the French Mandate of Syria. Unlike other regions historically belonging to Syrian provinces (such as Aintab, Kilis and Urfa), Alexandretta was confirmed as Syrian territory in the Treaty of Lausanne agreed upon by Kemal Atatürk; although it was granted a special autonomous status because it contained a large Turkish minority. However, culminating a series of border disputes with France-mandated Syria, Atatürk obtained in 1937 an agreement with France recognizing Alexandretta as an independent state, and in 1939 this state, called the Republic of Hatay, was annexed to Turkey as the 63rd Turkish province following a controversial referendum. Syria bitterly disputed both the separation of Alexandretta and its subsequent annexation to Turkey.

Syria maintains that the separation of Alexandretta violated France's mandatory responsibility to maintain the unity of Syrian lands (article 4 of the mandate charter). It also disputes the results of the referendum held in the province because, according to a League of Nations commission that registered voters in Alexandretta in 1938, Turkish voters in the province represented no more than 46% of the population.[15] Syria continues to consider Hatay part of its territory, and shows it as such on its maps.[16][17] However, Turkey and Syria have strengthened their ties and opened the border between the two countries.

Syrians hold the view that this land was illegally ceded to Turkey by France, the mandatory occupying power of Syria in the late 1930s. Syria still considers it an integral part of its own territory. Syrians call this land Liwa' aliskenderun (Arabic: لواء الاسكندرون) rather than the Turkish name of Hatay. Official Syrian maps still show Hatay as part of Syria.[16][17]

Under the leadership of Syrian President Bashar al Assad from 2000 onwards there was a lessening of tensions over the Hatay issue. Indeed, in early 2005, when visits from Turkish President Ahmet Necdet Sezer and Turkish prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan opened a way to discussions between two states, it was claimed that the Syrian government announced it had no claims to sovereignty concerning Hatay any more. On the other hand, there has been no official announcement by the Syrians relinquishing their rights of sovereignty.

Following changes to Turkish land registry legislation in 2003 a large number of properties in Hatay were purchased by Syrian nationals, mostly people who had been residents of Hatay since the 1930s but had retained their Syrian citizenship and were buying the properties that they already occupied. By 2006 the amount of land owned by Syrian nationals in Hatay exceeded the legal limit for foreign ownership of 0.5%, and sale of lands to foreigners was prohibited.[18]

There has been a policy of cross border co-operation, on the social and economic level, between Turkey and Syria in the recent years. This allowed families divided by the border to freely visit each other during the festive periods of Christmas and Eid. In December 2007 up to 27,000 people crossed the border to visit their brethren on the other side.[19] In the wake of an agreement in the autumn of 2009 to lift visa requirements, nationals of both countries can travel freely.[20] However, out of 50 agreements signed between Turkey and Syria in December 2009, the Hatay dispute stalled a water agreement over the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Turkey asked Syria to publicly recognize Hatay as a Turkish territory before signing on to the agreement.[21]

Apart from maps showing Hatay as Syrian territory, the Syrian policy has been to avoid discussing Hatay and giving evasive answers when asked to specify Syrian future goals and ambitions with regard to the area. This has included a complete media silence on the issue.[22] In February 2011 the dispute over Hatay was almost solved. The border separating Syria from Hatay was going to be blurred by a shared Friendship Dam on the Orontes river and as part of this project the two states had agreed on the national jurisdiction on each side of the border. Only weeks before the outbreak of the Syrian uprising and later war, groundbreaking ceremonies were held in Hatay and Idlib. As a result of the Syrian war and the extremely tense Turkish-Syrian relations it brought, construction was halted. As part of the ongoing war, the question of the sovereignty of Hatay has resurfaced in Syria and the Syrian media silence has been broken. Syrian media began broadcasting documentaries on the history of the area, the Turkish annexation and "Turkification" policies. Syrian newspapers have also reported on demonstrations in Hatay and on organizations and parties in Syria demanding an "end to the Turkish occupation".[23] However, although the Syrian government has repeatedly criticized the Turkish policies towards Syria and the armed rebel groups operating on Syrian territory, it has not officially brought up the question of Hatay.[24]

Geography

Hatay is traversed by the north-easterly line of equal latitude and longitude. 46% of the land is mountain, 33% plain and 20% plateau and hillside. The most prominent feature is the north-south leading Nur Mountains and the highest peak is Mığırtepe (2240m), other peaks include Ziyaret dağı and Keldağ (Jebel Akra or Casius) at 1739 m. The folds of land that make up the landscape of the province were formed as the land masses of Arabian-Nubian Shield and Anatolia have pushed into each other, meeting here in Hatay, a classic example of the Horst–graben formation. The Orontes River rises in the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon and runs through Syria and Hatay, where it reserves the Karasu and the Afrin River. It flows into the Mediterranean at its delta in Samandağ. There was a lake in the plain of Amik but this was drained in the 1970s, and today Amik is now the largest of the plains and an important agricultural center. The climate is typical of the Mediterranean, with warm wet winters and hot, dry summers. The mountain areas inland are drier than the coast. There are some mineral deposits, İskenderun is home to Turkey's largest iron and steel plant, and the district of Yayladağı produces a colourful marble called Rose of Hatay.

Climate

Hatay has a Mediterranean climate which has very hot, long and dry summers with cool rainy winters.

| Climate data for Hatay | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.3 (54.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.2 (84.6) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.1 (88) |

27.6 (81.7) |

20.1 (68.2) |

13.9 (57) |

23.28 (73.92) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.2 (54) |

16.3 (61.3) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

21.1 (70) |

15.4 (59.7) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

13.98 (57.15) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 172.7 (6.799) |

156.8 (6.173) |

141.3 (5.563) |

101.5 (3.996) |

90.4 (3.559) |

20.4 (0.803) |

21.9 (0.862) |

5.9 (0.232) |

39.8 (1.567) |

74.0 (2.913) |

114.2 (4.496) |

172.1 (6.776) |

1,111 (43.739) |

| Average rainy days | 14.2 | 13.5 | 12.8 | 9.8 | 5.8 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 3.8 | 7.5 | 9.7 | 13.3 | 96.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 105.4 | 123.2 | 186 | 225 | 297.6 | 330 | 356.5 | 337.9 | 291 | 220.1 | 147 | 102.3 | 2,722 |

| Source: Devlet Meteoroloji İşleri Genel Müdürlüğü [25] | |||||||||||||

Demography

Majority of population adheres to Islam belonging to either Alawi branch of Shia Islam or Sunni Islam. But other minorities are also found including Syriac Orthodox, Syriac Catholics, Maronites, Antiochian Greeks and Armenian communities. The village of Vakıflı in the district of Samandağ is Turkey's last remaining rural Armenian community while Arabs form the majority in three districts out of the twelve: Samandağ (Suwaidiyyah) (Alawi), Altınözü (Qusair) and Reyhanlı (Rihaniyyah) (Sunni). Unlike most Mediterranean provinces, Hatay has not experienced mass migration from other parts of Turkey in recent decades and has therefore preserved much of its traditional culture; for example, Arabic is still widely spoken in the province.[26] To celebrate this cultural mix, in 2005 "Hatay Meeting of Civilisations" congress was organised by Dr Aydın Bozkurt of Mustafa Kemal University and his "Hatay Association for the Protection of Universal Values".[27]

During the Syrian Civil War, the province experienced an influx of refugees. According to official figures, as of 21 April 2016, 408,000 Syrian refugees lived in the province.[28]

Education

Mustafa Kemal University is one of Turkey's newer tertiary institutions, founded in İskenderun and Antakya in 1992.

Transport

The province is served by Hatay Airport, as well as inter-city buses.

Languages

Until annexation, Turkish and Arabic were both spoken, after Ataturk's Reforms, however, the use of Arabic began to decline. Less than a generation ago, a child of an Arabic-speaking family would start school unable to speak Turkish; these days, most children of Arabic families start school unable to speak much, if any, Arabic. Some Arabic speakers will deny being "Arab," a term that can be derogatory in Turkey.[29]

Turkey's policies on language have focused on imposing homogeneity. The degree of imposition peaked in 1983, when the military government introduced a law prohibiting (to varying degrees) languages other than Turkish. For speakers of some languages (those not using a first official language of a country recognized by Turkey), the law forbade the use of those languages, even during private conversation. (Rumpf, 1989) Although the law was repealed in 1991, the Constitution still prohibits any institution from teaching a language other than Turkish as a mother tongue (Article 42.9; provisions in international treaties are ostensibly upheld even today).[29]

85% of Arabs in Hatay believe that the use of Arabic is decreasing, however, 15% who hear it on a daily basis, disagree that such is happening in the region. The Arab Christian minority has the right to teach Arabic under the Treaty of Lausanne, however they tend to refrain from doing so in order to avoid sectarian tensions as the treaty does not apply to the Muslim majority.[29]

Districts

Hatay province was divided into 12 districts: Altınözü, Antakya, Belen, Dörtyol, Erzin, Hassa, İskenderun, Kırıkhan, Kumlu, Reyhanlı, Samandağ and Yayladağı.

In 2014, 3 more districts were created: Defne, Arsuz and Payas.

Cuisine

Hatay is warm enough to grow tropical crops such as sweet potato and sugar cane, and these are used in the local cuisine, along with other local specialities including a type of cucumber/squash called kitte. Well-known dishes of Hatay include the syrupy-pastry künefe, squash cooked in onions and tomato paste (sıhılmahsi), the aubergine and yoghurt paste (Baba ghanoush), and the chickpea paste hummus as well as dishes such as kebab which are found throughout Turkey. In general the people of Hatay produce many spicy dishes including the walnut and spice paste muhammara), the spicy köfte called oruk, the thyme and parsley paste Za'atar and the spicy sun-dried cheese called Surke. Finally, syrup of pomegranate (nar ekşisi) is a popular salad dressing particular to this area.

Landmarks

- World's second-largest collection of Roman mosaics in Antakya museum

- Rock-carved Church of St Peter in Antakya, a site of Christian pilgrimage.

- Gündüz cinema, once parliament building of the Republic of Hatay.

- Titus Tunnel of Vespasian, in Samandağı, built as a water channel in the 2nd century.

- Castles: Koz Castle, Bakras Castle, Payas Castle, Mancınık Castle, Cin Castle, Darbısak Castle[30]

Notable residents

- Mehmet Aksoy - sculptor (b. Antakya 1939 - )

- Gökhan Zan - Galatasaray footballer, (b. Antakya 1981 )

- Selçuk İnan - Galatasaray footballer, (b. İskenderun 1985 )

- İsmail Köybaşı - Beşiktaş footballer, (b. İskenderun 1989 )

- Yasin Özdenak - Retired Galatasaray footballer, (b. İskenderun 1948 )

- Selami Şahin - musician, composer and actor (b. Yayladağı 1948 )

Films

- Hatay figured in the Indiana Jones movie Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, where it was portrayed as the final resting place of the Holy Grail in the "canyon of the crescent moon" outside of Alexandretta. In the movie, the Nazis offer the "sultan of Hatay" precious valuables to compensate for removing the Grail from his borders. He ignores the valuables, but accepts their Rolls-Royce Phantom II.

- The Turkish film Propaganda (1999) by Sinan Çetin, portrays the difficult materialisation of the Turkish-Syrian border in 1948, cutting through villages and families.

- The 2001 film Şelale by local director Semir Aslanyürek was filmed in Hatay.

See also

- List of populated places in Hatay Province

- Çukurova

- Harbiye

- Kışlak

- Payas

- Baku–Supsa Pipeline

- Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline

References

- ↑ Turkish Statistical Institute, MS Excel document – Population of province/district centers and towns/villages and population growth rate by provinces

- ↑ Map from 1764 of Alexandrette

- ↑ William M. Hale Turkish Foreign Policy, 1774-2000 p.45 Routledge, 2000 ISBN 0714650714, 9780714650715

- ↑

- ↑ Khater, Akram Fouad (2010). Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East. Cengage Learning. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-11178-485-0.

(In 1921 there were only 87,000 Turks amid a population of 220,000 that was primarily Arab)

- ↑ Duiker & Spielvogel 2012, 192.

- ↑ Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2006). Turkey Beyond Nationalism: Towards Post-Nationalist Identities. I.B.Tauris. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-84511-141-0.

According to official French statistics of 1936 the total population (219,080) was made up as follows: Turks 38% Alawite Arabs 28% Sunni Arabs 10 Christians Arabs 8%

- ↑ Brandell, Inga (2006). State Frontiers: Borders and Boundaries in the Middle East. I.B.Tauris. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-84511-076-5. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

According to estimates provided by the French High Commission in 1936, out of a population of 220,000 39 per cent were Turks, 28 per cent Alawites, 11 per cent Armenians, 10 per cent Sunni Arabs, 8 per cent other Christians, while Circassians, Jews and Kurds made up the remaining 4 per cent.

- ↑ Jack Kalpakian (2004). Identity, Conflict and Cooperation in International River Systems (Hardcover ed.). Ashgate Publishing. p. 130. ISBN 0-7546-3338-1.

- ↑ Robert Fisk (19 March 2007). "Robert Fisk: US power games in the Middle East". The Independent. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ Robert Fisk (2007). The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East (Paperback ed.). Vintage. p. 335. ISBN 1-4000-7517-3.

- ↑ Çağatay, Soner. Islam, secularism, and nationalism in modern Turkey: who is a Turk? Volume 4 of Routledge studies in Middle Eastern history. p. 119-120. Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 0-415-38458-3, ISBN 978-0-415-38458-2

- ↑ Emma Jorum (2014). Beyond Syria's Borders: A History of Territorial Disputes in the Middle East. I.B. Tauris. pp. 92, 93.

- ↑ "ARMENIA AND KARABAGH" (PDF). Minority Rights Group. 1991. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ↑ Arnold Twinby, 1938 Survey of International Affairs p. 484

- 1 2 parliament.gov.sy - معلومات عن الجمهورية العربية السورية

- 1 2 "The Alexandretta Dispute", American Journal of International Law

- ↑ Hürriyet - Hatay'da yabancılara gayrimenkul satışı durduruldu

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ PM vows to build model partnership with Syria Today's Zaman 23 December 2010

- ↑ Lundgren Jörum, Emma: "The Importance of the Unimportant" in Hinnebusch, Raymond & Tür, Özlem: Turkey-Syria Relations: Between Enmity and Amity (Farnham: Ashgate), p 114-122.

- ↑ http://carnegieendowment.org/syriaincrisis/?fa=54340

- ↑ Lundgren Jörum, Emma: Beyond Syria's Borders: A history of territorial disputes in the Middle East (London & New Yor: I.B. Tauris), p 108

- ↑ http://www.dmi.gov.tr/veridegerlendirme/il-ve-ilceler-istatistik.aspx?m=HATAY

- ↑ Radikal-çevrimiçi / Türkiye / Samandağ'da 'Alluş'la dans

- ↑ Spiritual leaders speak up in Hatay for global peace - Turkish Daily News Sep 27, 2005

- ↑ ""Mültecilerin Şartları Kötü, Hatay'da Herkes Tedirgin"" (in Turkish). Bianet. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 http://www.culturalsurvival.org/ourpublications/csq/article/for-reasons-out-our-hands-a-community-identifies-causes-language-shift

- ↑ "Kaleler" (in Turkish). Hatay Directorate of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hatay Province. |

- Hatay News

- pictures Photo Gallery

- the provincial governor's website

- Pictures of Antakya

- Pictures of Antakya Museum

- Pictures of Hatay

- Flag and info of the Republic of Hatay

- Hatay Weather Forecast Information

- Hatay Radio Stations

- Tourist Information and pictures about Hatay/Antakya with Webcams and weather information

- Hatay Radio Station

- Turkish

Coordinates: 36°25′49″N 36°10′27″E / 36.43028°N 36.17417°E