American Legion

|

| |

| Motto | "For God and Country" |

|---|---|

| Established | March 16, 1919 |

| Founder | Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. |

| Type | Veterans' organization |

| 35-0144250 | |

| Legal status | Federally chartered corporation |

| Headquarters | 700 N. Pennsylvania St., Indianapolis, Indiana |

Region served | Worldwide |

Membership (2014) | 2,400,000 |

National Commander | Charles E. Schmidt |

National Vice Commanders |

|

| National Executive Committee | |

| Publication | The American Legion |

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Secessions | 40 and 8 |

| Affiliations | Patriot Guard Riders |

| Website |

legion |

The American Legion, Inc., is a wartime veterans' organization formed in Paris on March 16, 1919, by members of the American Expeditionary Forces.[1] It was chartered by Congress on September 16, 1919. The veterans' organization is headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana, and also has offices in Washington, D.C.[2]

In addition to organizing commemorative events, volunteer veterans operating through The American Legion support activities and provide assistance at Veterans Administration hospitals and clinics. The American Legion is active in issue-oriented U.S. politics. Its primary political activity is lobbying on behalf of interests of veterans and service members, including support for veterans benefits such as pensions and the Veterans Health Administration. The veterans' organization has also historically promoted Americanism and opposed Communism in the United States, providing names of persons and organizations to the Hollywood blacklist.

Eligibility

American veterans who served at least one day of active federal duty during wartime, or are serving now, are potentially eligible for membership in The American Legion. Members must have been honorably discharged or still serving honorably. United States Merchant Marines who served from December 7, 1941, to December 31, 1946, are also eligible.[3]

Veterans who served during the following wars are eligible:

| War or conflict | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Southwest Asia and Global War on Terrorism | August 2, 1990 | Present day |

| Panama | December 20, 1989 | January 31, 1990 |

| Lebanon and Grenada | August 24, 1982 | July 31, 1984 |

| Vietnam War | February 28, 1961 | May 7, 1975 |

| Korean War | June 25, 1950 | January 31, 1955 |

| World War II | December 7, 1941 | December 31, 1946 |

Veterans of World War I were also eligible during their lifetimes; the last American World War I veteran, Frank Buckles, died in 2011.

| War or conflict | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| World War I | April 6, 1917 | November 11, 1918 |

History

Membership peaked for The American Legion right after World War II, when enrollments doubled from 1.7 million to 3.3 million. After the Korean War, there were 2.5 million Legionnaires. As baby boomers joined, membership increased to 3.1 million in 1992. However, membership has slowly been decreasing since then. In 2013, the Legion reported 2.3 million members.[4]

19th century

The aftermath of two American wars in the second half of the 19th century had seen the formation of several ex-soldiers' organizations. Former Union Army soldiers of the American Civil War of 1861–65 established a fraternal organization called the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), while their Southern brethren would join together in the United Confederate Veterans (UCV).[5] Both organizations emerged as powerful political entities, with the GAR serving as a mainstay of the Republican Party, which controlled the Presidency from the Civil War through Theodore Roosevelt's administration except for the two terms of office of Grover Cleveland.[5] In Southern politics the UCV maintained an even more dominant position as a bulwark of the Democratic Party which dominated there.[5] The conclusion of the brief Spanish–American conflict of 1898 ushered in another soldiers' organization, the American Veterans of Foreign Service, today known as the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW).[6]

1915 American Legion

"The Legion believes in making instantly available to our country, in case of war, all men who already have military or technical training valuable in modern warfare by land or sea. Members of the Legion enroll themselves in advance for this purpose to be used as the Government (not they themselves) may see fit, according to their qualifications."

Concerned about the United States' absence from the world war and the preparedness of its army and navy, magazine editor Arthur Sullivant Hoffman and writer Stephen Allan Reynolds founded the American Legion in February 1915, inspired by a letter from reader E. D. Cook.[8][9] They lobbied government to strengthen the military. They held a preparedness parade in New York City and made a film America Prepare [7] Officers included Theodore Roosevelt, Arthur S. Hoffman, William Howard Taft, Elihu Root Jacob M. Dickinson, Henry L. Stimson and Luke E. Wright, George von L. Meyer, Truman H. Newberry and Charles J. Bonaparte. Its officers were at 10 Bridge Street, New York City.[10]

In 1917, when war was declared the legion had 23,000 members[7] skilled in 77 professions[8] pledged to fight. Their pledge cards were shared with the government and ultimately used to raise two regiments of air mechanics. The legion was discorporated in 1917.[11][12]

Post World War I

With the termination of hostilities in World War I in November 1918, some American officers who had been participants in the conflict began to think about creating a similar organization for the two million men who had been on European duty.[6] The need for an organization for former members of the AEF was pressing and immediate. With the war at an end, hundreds of thousands of impatient draftees found themselves trapped in France and pining for home, certain only that untold weeks or months lay ahead of them before their return would be logistically possible.[13] Morale plummeted.[13] Cautionary voices were raised about an apparent correlation between disaffected and discharged troops and the Bolshevik uprisings taking place in Russia, Finland, Germany, and Hungary.[13]

This situation was a particular matter of concern to Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., eldest son of the 26th President. One day in January 1919, Roosevelt had a discussion at General Headquarters with a mobilized National Guard officer named George A. White, a former newspaper editor with the Portland Oregonian.[14] After long discussion, Roosevelt suggested the establishment at once of a new servicemen's organization including all members of the AEF, as well as those soldiers who remained stateside as members of the army, navy, and Marine Corps during the war without having been shipped abroad.[14] Roosevelt and White advocated ceaselessly for this proposal until ultimately they found sufficient support at headquarters to move forward with the plan. General John J. Pershing issued orders to a group of 20 non-career officers to report to the YMCA headquarters in Paris on February 15, 1919.[15] The selection of these individuals had been made by Roosevelt.[15] They were joined with a number of regular Army officers Pershing selected himself.[16]

The session of reserve and regular officers was instructed to provide a set of laws to curb the problem of declining morale.[15] After three days, the officers presented a series of proposals, including eliminating restrictive regulations, organizing additional athletic and recreational events, and expanding leave time and entertainment programs.[17] At the end of the first day, the officers retired to the Inter-Allied Officers Club, a converted home across the street from the YMCA building.[16] There Lt. Col. Roosevelt told them his proposal for a new veterans' society.[18] Most of those present were rapidly won to Roosevelt's plan.[19] The officers decided to make all of their actions provisional until an elected convention of delegates could be convened and did not predetermine a program for the unnamed veterans organization.[19] Instead, they chose to expand their number with a large preliminary meeting which would consist of an equal number of elected delegates to represent both enlisted men and commissioned officers.[20]

A provisional executive committee of four people emerged from the February 15 "Roosevelt dinner": Roosevelt in the first place, who was to return to the United States and obtain his military discharge when able, and then to gather assistants and promote the idea of the new veterans' organization among demobilized troops there; George White, who was to travel France touring the camps of the AEF explaining the idea in person; Secretary of the group was veteran wartime administrator Eric Fisher Wood, together with former Ohio Congressman Ralph D. Cole, Wood was to establish a central office and to maintain contact by mail and telegram with the various combat divisions and headquarters staffs, as well as to publicize activities to the press.[21]

Preparations for a convention in Paris began apace. A convention call was prepared by Wood and "invitations" distributed to about 2,000 officers and enlisted men and publicized in the March 14, 1919 issue of Stars and Stripes.[22] The convention call expressed the desire to form "one permanent nation-wide organization...composed of all parties, all creeds, and all ranks who wish to perpetuate the relationships formed while in military service."[23] In addition to the personal invitations distributed, the published announcement indicated that "any officer or enlisted man not invited who is in Paris at the time of the meeting is invited to be present and to have a voice in the meeting."[23] The conclave was slated to begin on March 15.

The site of Ferdinand Branstetter Post No. 1 of The American Legion is a vacant lot in Van Tassell, Wyoming, where the first American Legion post in the United States was established in 1919. The post was named after Ferdinand Branstetter, a Van Tassell resident who died in World War I. The structure housing the post has since been demolished. The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969. In 1969, it was hoped that an interpretative sign would be put up, and also possibly that a restored post building would be constructed.[24]

The first post of The American Legion, General John Joseph Pershing Post Number 1 in Washington, D.C., was organized on March 7, 1919, and obtained the first charter issued to any post of the Legion on May 19, 1919. The St. Louis caucus that same year decided that Legion posts should not be named after living persons, and the first post changed its name to George Washington Post 1. The post completed the constitution and made plans for a permanent organization. It set up temporary headquarters in New York City and began its relief, employment, and Americanism programs.

Congress granted The American Legion a national charter in September 1919.

American Legion China Post One, formed in 1919 one year after the "great war" and chartered by The American Legion on April 20, 1920, was originally named the General Frederick Townsend Ward Post No. 1, China.[25] It is the only Post nominally headquartered in a Communist country, and has been operating in exile since 1948 – presently in Fate, Texas.[26]

The Paris Caucus (March 15–17, 1919)

Having immediately received a blizzard of acceptances to attend the opening of the "Liberty League Caucus", as he had begun to refer to it, Temporary Secretary Eric Fisher Wood began to search for use of a room of sufficient size to contain the gathering.[28] The Cirque de Paris had been retained, a large, multisided amphitheater sufficient to accommodate a crowd of about 2,000.[29] Delegates began to assemble from all over France. The 10:00 am scheduled start was delayed due to various logistical problems, with a beginning finally made shortly after 2:45 pm.[30]

As "Temporary Chairman" Teddy Roosevelt, Jr. had already departed for America, the session was gaveled to order by Eric Wood, who briefly recounted Roosevelt's idea and the story of the 20 AEF officers who had jointly helped to give the new organization form.[30] In his keynote opening remarks Wood recommended to the delegates of the so-called Paris Caucus that they do three things: first, set up an apparatus to conduct a formal founding conference in the United States sometime in the winter; second, the body should draft a tentative name for the organization; and finally, the body should compose a provisional constitution to be submitted to the founding convention for its acceptance or rejection.[31]

Convention rules were decided upon and four 15-member committees were chosen.[32] The Committee on Name reported back that they had considered a dozen potential names, including Veterans of the Great War, Liberty League, American Comrades of the Great War, Legion of the Great War, and The American Legion, among others.[33] This list was whittled down to five ranked choices for the consideration of the Caucus, with "The American Legion" the preferred option.[33] It was noted in passing during the course of debate on the topic that Teddy Roosevelt, Jr. had been responsible for an earlier organization called "The American Legion" in 1914, a "preparedness" society with a claimed membership of 35,000 which had been absorbed into the Council of National Defense in 1916.[34]

The Committee on Constitution reported with a report containing the draft of a Preamble for the organization, specifying organizational objectives.[33] This document stated that the group

... desiring to perpetuate the principles of Justice, Freedom, and Democracy for which we have fought, to inculcate the duty and obligation of the citizen to the State; to preserve the history and incidents of our participation in the war; and to cement the ties of comradeship formed in service, do propose to found and establish an Association for the furtherance of the foregoing purposes.[35]

The majority report of the Committee on Convention recommended that 11 am on November 11, 1919—one year to the hour after the termination of hostilities in World War I—be selected as the date and time for the convocation of a national convention.[35] No location was specified.[35]

The Committee on Permanent Organization recommended an organization based upon territorial units rather than those based upon military organizations, governed by an Executive Committee of 50, with half of these coming from the officer corps and the other half coming from the ranks of enlisted men.[36]

The St. Louis Caucus (May 8–10, 1919)

The Paris Caucus in March was by its nature limited to soldiers of the AEF who remained in Europe; a parallel organizational meeting for those who had returned to the American preparatory to a formal organizational convention was deemed necessary. This was a conclave dominated by the presence of Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., who called the convention to order amidst mass chanting akin to that of a Presidential nominating convention—"We Want Ted-dy! We Want Ted-dy!"[37]

A minor crisis followed when Roosevelt twice declined nomination for permanent chairman of the session, to the consternation of many overwrought delegates, who sought to emphasize the symbolism of President Theodore Roosevelt's son maintaining the closest of connections with the organization.[38]

The work of the St. Louis Caucus was largely shaped by the fundamental decisions made by the earlier Paris Caucus. Its agenda was in addition carefully prepared by a 49-member "Advance Committee", which included at least one delegate from each fledgling state organization and which drew up a draft program for the organization in advance of the convention's opening.[39]

As time before the scheduled start of the convention was short, delegation to the assembly was highly irregular. On April 10, 1919, Temporary Secretary Eric Fisher Wood mailed a letter to the Governor of every state, informing them of the forthcoming gathering and making note of the non-partisan and patriotic nature of the League.[40] Follow-up cables by Roosevelt and Wood encouraged the organization of state conventions to select delegates.[40] This was, however, largely a failed formality, as states lacked sufficient time to organize themselves and properly elect delegates to St. Louis.[40] In practice, the fledgling organization's provisional Executive Committee decided to allow each state delegation twice as many votes at that state had in the United States House of Representatives and left it to each to determine how those votes were apportioned.[40]

Participants at the St. Louis Caucus were enthusiastic although the session was not a productive one. Fully two days were invested choosing ceremonial officers and selecting Minneapolis as the site for the organization's formal Founding Convention in the fall.[41] Over 1100 participants competed to gain the floor to speechify, leading one historian to describe the scene as a "melee" in which "disorder reigned supreme."[42] Consequently, passage of the program by the gathering was largely a pro forma exercise, rushed through during the session's last day, with the actual decision-making process involving such matters as the constitution and publications of the organization being done in committee at night.[41]

The preamble of the constitution adopted in St. Louis became one of the seminal statements of the Legion's orientation and objectives:[43]

For God and Country we associate ourselves together for the following purposes:

To uphold and defend the Constitution of the United States of America; to maintain law and order; to foster and perpetuate a 100 Percent Americanism; to preserve the memories and incidents of our association in the Great War; to inculcate a sense of individual obligation to the community, state, and nation; to combat the autocracy of both the classes and the masses; to make right the master of might; to promote peace and good will on earth; to safeguard and transmit to prosperity the principles of justice, freedom, and democracy; to consecrate and sanctify our comradeship by devotion to mutual helpfulness.

The St. Louis Caucus spent much of its time discussing resolutions: whether a stand should be taken on the League of Nations, Prohibition, or the implementation of universal military service, whether posts composed of Negro soldiers should be established, and whether Secretary of War Newton D. Baker should be impeached for his apparent leniency towards conscientious objectors in the months after the war.[44]

A particularly hard line was taken towards the American radical movement, with one resolution passed on the final day calling on Congress to "pass a bill or immediately deporting every one of those Bolsheviks or Industrial Workers of the World."[45] Minneapolis, Minnesota was chosen for the site of the founding convention of the organization in November over the more centrally-located Chicago after much acrimonious debate about the perceived political transgressions of the Chicago city administration.

Founding Convention (November 10–12, 1919)

The formal founding convention was held in Minneapolis, Minnesota from November 10 to 12, 1919. It was attended by 684 delegates from around the United States.[47]

From the outset The American Legion maintained a strictly nonpartisan orientation towards electoral politics. The group wrote a specific prohibition of the endorsement of political candidates into its constitution,[48] declaring:

...this organization shall be absolutely non-political and shall not be used for the dissemination of partisan principles or for the promotion of the candidacy of any person seeking public office or preferment; and no candidate for or incumbent of a salaried elective public office shall hold any office in The American Legion or in any branch or post thereof.

One semi-official historian of the organization has noted the way that this explicit refusal to affiliate with one or another political party had the paradoxical effect of rapidly building great political power for the organization, as politicians from both of the "old parties" competed for the favor of the Legion's massive and active membership.[49]

One of the gathering's primary accomplishment was the establishment of a permanent National Legislative Committee to advance the Legion's political objectives as its lobbying arm.[50] The first iteration of this official Washington, DC-based lobby for the Legion included only four members—two Republicans and two Democrats.[51] After 1920 the National Legislative Committee was expanded to consist of one member from each state, with additional effort made at the state level to exert pressure upon various state legislatures.[51]

Chief on the Legion's legislative agenda was a dramatic improvement of the level of compensation for soldiers who suffered permanent disability during the war. At the time of the end of World War I, American law stated that soldiers who suffered total disability were to receive only the base pay of a Private—$30 per month.[52] The Legion concentrated its lobbying effort in 1919 on passage of legislation increasing payment for total disability suffered in the war to $80 a month—a sum roughly sufficient in dollars of the day to provide a living wage.[52] Those partially disabled by their wounds were to receive lesser payments.[52] A flurry of lobbying by the Legion's National Legislative Committee in conjunction with cables sent to Congressional leaders by National Commander Franklin D'Olier helped achieve passage of this legislation by the end of 1919.[52]

The American Legion's chief base of support during its first years was among the officers corps of the reserves and the National Guard.[53] The size of the regular army was comparatively small and its representation in the League in its earliest days was even more limited. Consequently, for nearly two decades The American Legion maintained a largely isolationist perspective, best expressed in three resolutions passed by the Minneapolis founding convention:

1. That a large standing army is uneconomic and un-American. National safety with freedom from militarism is best assured by a national citizen army and navy based on the democratic principles of equality of obligation and opportunity for all.

2. That we favor universal military training and the administration of such a policy should be removed from the complete control of any exclusively military organization or caste.

3. That we are strongly opposed to compulsory military service in time of peace.[54]

Additional resolutions passed by the founding convention emphasized the need for military preparedness, albeit maintained through a citizens' army of reservists and National Guardsmen rather than through the costly and undemocratic structure of a vast standing army led by a professional military caste.[54] This nationalist isolationism would remain in place until the very eve of American entry into the Second World War.

Departments and posts overseas

On November 9, 1919, the National Headquarters of The American Legion accredited Lt. Col. Francis E. Drake as the Commander of The Department of France; on February 7, 1921, in the National Executive Committee meeting held at Washington D.C., the Department of France was created with Posts in Belgium, France, Germany, Poland, and Turkey.[55] On April 20, 1920, American Legion China Post One, originally formed in 1919 and named General Frederick Townsend Ward Post No. 1, was chartered in Shanghai. During the lead up to World War II, members assisted retired US Army Captain Claire Lee Chennault in formation of the American "Flying Tigers" and the Republic of China Air Force.[25] The Post has been operating in exile since 1948—presently in Fate, Texas.[26]

Centralia Massacre of 1919

November 11, 1919, the first anniversary of Armistice Day and the occasion of the American Legion's formal launch at its Minneapolis Founding Convention, was also a historical moment of violence and controversy. On that day a parade of Legionnaires took place in the mill town of Centralia, located in Southwestern Washington.[56] Plans were made by some of the marchers at the conclusion of their patriotic demonstration to storm and ransack the local hall maintained by the Industrial Workers of the World, a labor union which had been the target of multiple arrests, large trials, and various incidents of mob violence nationally during the months of American participation in World War I.[56] Plans for this less-than-spontaneous act of violence had made their way to the ears of the union members (commonly referred to as Wobblies), however, and 30 or 40 IWW members had been seen coming and going at their hall on the day of the march—some of whom were observed carrying guns.[56]

At 2 pm the march began at the city park, led by a marching band playing "Over There."[57] Marchers included Boy Scouts, members of the local Elks Lodge, active-duty sailors and marines, with about 80 members of the newly established Centralia and Chehalis American Legion posts bringing up the rear.[57] As the parade turned onto Tower Avenue and crossed Second Street, it passed IWW Hall on its left.[57] The parade stopped and Legionnaires surrounded the hall.[57]

Parade Marshal Adrian Cormier rode up on horseback and, according to some witnesses, blew a whistle giving the signal to the Legionnaires to charge the IWW headquarters building.[57] A group of marchers rushed the hall, smashing the front plate glass window and attempting to kick in the door.[57] Just as the door gave way, shots were fired from within at the intruders.[57] This provided the signal to other armed IWW members, who were stationed across the street to set up a crossfire against potential invaders and they also began firing on the Legionnaires.[58] In less than a minute the firing was over, with three AL members left dead or dying and others wounded.[59]

Taken by surprise by the armed defense of IWW headquarters, many Legionnaires rushed home to arm themselves, while others broke into local hardware stores to steal guns and ammunition.[59] Now armed, a furious mob reassembled and charged the IWW Hall again, capturing six IWW members inside.[59] The mob proceeded to destroy the front porch of the hall and a large bonfire was built, upon which were torched the local Wobblies' official records, books, newspapers, and mattresses.[59]

One local Wobbly named Wesley Everest escaped through a back door when he saw the mob approaching the hall.[59] He fled into nearby woods, exchanging gunshots with his pursuers.[59] One of those chasing the fleeing IWW man was hit in the chest several times with bullets and was killed, running the death count of Legionnaires to four.[59] Everest was taken alive, kicked and beaten, and a belt wrapped around his neck as he was dragged back to the town to be lynched.[59] Local police intervened, however, and Everest was taken to jail, where he was thrown down on the concrete floor.[59] At 7:30 pm, on cue, all city lights in town went out for 15 minutes and Legionnaires stopped cars and forced them to turn out their headlights.[60] The Elks Hall gathering entered the jail without meeting resistance and took Wesley Everest, dragging him away to a waiting car but leaving other incarcerated Wobblies in jail cells unhindered.[61] A procession of six cars drove west to a railroad bridge across the Chehalis River.[62]

A rope was attached to Everest's neck and he was pushed off the bridge, but the lynching attempt was bungled and Everest's neck was not snapped by the fall.[62] Everest was hauled up again, a longer rope was substituted, and Everest was pushed off the bridge again.[62] The lynch mob then shined their car headlights on the hanging form of Everest and shot him for good measure.[62]

Although a mob milled around the jail all night, terrorizing the occupants, no further acts of extra-legal retribution were taken.[62] Everest's body was cut down the next morning, falling into the riverbed below, where it remained all day.[63] As night fell Everest's body was hauled back to town, the rope still around his neck, where it was refused by local undertakers and left on the floor of the jail in sight of the prisoners all night.[63] No charges were ever filed in connection with the lynching.[64]

Twelve IWW members were ultimately indicted by a grand jury for first degree murder in connection with the killing of the four Legionnaires and a local left wing lawyer was charged as an accessory to the crime.[64] A January 1920 trial resulted in the conviction of six defendants on charges of second degree murder.[65]

1920s

The American Legion was very active in the 1920s. The organization was formally non-partisan, endorsing candidates of no political party. Instead the group worked to the spread of the ideology of Americanism and acted as an lobbying organization on behalf of issues of importance to veterans, with particular emphasis on winning a "soldier's bonus" payment from the government and for the alleviation of the unemployment to which many soldiers returned. The Legion also served a strong social function, building and buying "clubhouses" in communities across America at which its members could gather, reflect, network, and socialize.

The Legion's efforts to promote Americanism during the 1920s included urging its members to report on the publication materials perceived to be subversive, left-wing, or reflective of radical foreign political views, and established a National Americanism Commission to oversee its actions related to subversive activities.[66] It commissioned the development of textbooks that promoted American patriotism, worked with members of the National Education Association to promote the teaching of history from an American perspective, and sought the removal of textbooks it saw as "un-American".[67] It also supported legislation restricting immigration and seditious speech,[68] and used its influence in an effort to deny public forums to speakers whose views it opposed.[69]

In 1924, the Legion and other veterans organizations won their battle for additional compensation for World War I veterans with the passage of the World War Adjusted Compensation Act. Most payments were scheduled to be paid in 1945.[70]

In 1923, American Legion Commander Alvin Owsley cited Italian Fascism as a model for defending the nation against the forces of the left.[71] Owsley said:

If ever needed, The American Legion stands ready to protect our country's institutions and ideals as the Fascisti dealt with the destructionists who menaced Italy!... The American Legion is fighting every element that threatens our democratic government—Soviets, anarchists, IWW, revolutionary socialists and every other red.... Do not forget that the Fascisti are to Italy what The American Legion is to the United States.[72]

The Legion invited Mussolini to speak at its convention as late as 1930.[72]

The American Legion was instrumental in the creation of the U.S. Veterans' Bureau, now known as the Department of Veterans Affairs. The Legion also created its own American Legion Baseball Program, hosting national tournaments annually from 1926.

Commander Travers D. Carmen awarded Charles Lindbergh its "Distinguished Service Medal", the medal's first recipient, on July 22, 1927. American Legion national convention was held in Paris, France in September 1927. A major part of this was drum and bugle corps competition in which approximately 14,000 members took part.

1930s to 1950s

The American Legion Memorial Bridge in Traverse City, Michigan, was completed in 1930.[73] The Traverse City city commission decided to purchase dedication plaques for $100 at the request of The American Legion in 1930.[73]

The Sons of the American Legion formed at the American Legion's 14th National Convention in Portland, Oregon, on September 12–15, 1932. Membership is limited to the male descendants of members of The American Legion, or deceased individuals who served in the armed forces of the United States during times specified by The American Legion.[74]

In the spring of 1933, at the very beginning of his presidency, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sought to balance the federal budget by sharp reductions in veterans benefits, which constituted one quarter of the federal budget. The Economy Act of 1933 cut disability pensions and established strict new guidelines for proving disabilities. The American Legion generally supported the FDR administration and the Act, while the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) was loudly opposed. After a VFW convention heard speeches denouncing FDR's programs, The American Legion invited Roosevelt to speak and he won the convention's support. Nevertheless, the Legion's stance was unpopular with its membership and membership plummeted in 1933 by 20% as 160,000 failed to renew their memberships. The VFW then campaigned for a "Bonus Bill" that would immediately pay World War I veterans what they were due in 1945 under the 1924 World War Adjusted Compensation Act. The Legion's failure to take a similar position allowed the much smaller, less prestigious VFW to rally support while accusing the Legion of ties to the FDR Administration and business interests.

In December 1933, retired General Smedley Butler, a popular and colorful speaker, toured the country on behalf of the VFW, calling on veterans to organize politically to win their benefits.[75] Butler believed The American Legion was controlled by banking interests. On December 8, 1933, explaining why he believed veterans' interests were better served by the VFW than The American Legion, he said: "I said I have never known one leader of The American Legion who had never sold them out–and I mean it."[76] In November 1934, Butler told the New York Evening Post and a congressional subcommittee that representatives of powerful industrial interests and The American Legion were trying to induce him to lead the Legion in a campaign to preserve the gold standard and to engineer a coup against President Roosevelt with Butler's aid in marshaling the support of veterans. Everyone implicated denied involvement and the press gave the story little credence.

Nevertheless, Butler's charges, elaborated by articles in the Communist newspaper New Masses, gave birth to an enduring conspiracy theory, known as the Business Plot, that powerful business interests in alliance with the Legion planned to overthrow the federal government.[77]

In 1935, the first Boys' State convened in Springfield, Illinois. The American Legion's first National High School Oratorical Contest was held in 1938.

In 1942, the Legion adopted the practice of the VFW to become a perpetual organization, rather than die off as its membership aged as that of the Grand Army of the Republic was rapidly doing. The Legion's charter was changed to allow veterans of World War II to join. Throughout the 1940s, The American Legion was active in providing support for veterans and soldiers who fought in World War II. The American Legion wrote the original draft of the Veterans Readjustment Act, which became known as the *GI Bill. The original draft is preserved at the Legion's National Headquarters. The American Legion vigorously campaigned for the G.I. Bill, which was signed into law in June 1944.

The first Boys Nation program was held in 1946.

Late in 1950, at least some local Legion organizations began to support Senator Joe McCarthy, sponsoring his appearance at an "Americanism" rally in Houston. During his speech, the senator falsely claimed there were 205 Communists in the State Department.[78] The Legion also took a McCarthyist stance on film, threatening to boycott any theater that screened director Edward Dmytryk's Salt to the Devil (also known as Give Us This Day) (1949) because of Dmytryk's involvement with the blacklist.[79]

At the Legion's 1951 convention at Miami, Florida, it formally endorsed its "Back to God" movement.[80] When launching the program in 1953 with a national television broadcast that included speeches by President Eisenhower and Vice-President Nixon, the Legion's National Commander Lewis K. Gough said it promoted "regular church attendance, daily family prayer, and the religious training of children."[81]

The Legion's Americanism activities continued through the 1930s to the 1950s. It promoted the passage of state bills requiring loyalty oaths of school teachers, and supported the activities of anti-Communist newspaper publishers, including William Randolph Hearst, in identifying Communist sympathizers in academic institutions.[82] It was also influential in the creation of state-level legislative investigations into communist or un-American activities,[83] and staged a mock Communist takeover of Mosinee, Wisconsin that garnered national headlines.[84] Its programs were rejuvenated by increased membership after World War II, and in its 1950 convention called for members of the American Communist Party to be tried for treason. Along with the Veterans of Foreign Wars, it maintained files on supposed Communist sympathizers, and it shared the fruits of its research with government investigators.[85] Local posts picketed films they perceived as anti-American, and the national organization was formally involved in Hollywood's efforts to clear films of such influence.[86] The list of names and organizations the Legion provided to movie studios formed the basis for the Hollywood blacklist, and supported the work of the House Un-American Activities Committee and its predecessors before and during the Cold War. It was unsuccessful in applying pressure to the movie studios when the blacklist began to crumble in the late 1950s.[87]

The Legion's political activities were opposed from an early date by organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which characterized them as a danger to political and civil rights. In a report issued in 1921, the ACLU documented 50 instances of what it described as illegal acts of violence by Legionnaires.[69] In 1927, the ACLU reported that the Legion "had replaced the [Ku Klux] Klan as the most active agent of intolerance and repression in the country.[69] The Legion, for its part, branded the ACLU as a un-American organization at every convention it held between 1920 and 1962.[88] In 1952, the Legion asked for a congressional investigation into the ACLU to determine if it was a communist or communist front organization.[89]

Veterans of the Korean War were approved for membership in The American Legion in 1950, and the American Legion Child Welfare Foundation was formed in 1954.

1960s to 1980s

On May 30, 1969, the Cabin John Bridge, which carried the Capital Beltway (I-495) across the Potomac River northwest of Washington, D.C., was officially renamed to the "American Legion Memorial Bridge" in a ceremony led by Lt. Gen. Lewis B. Hershey, director of the U.S. Selective Service System.[90]

In 1976, an outbreak of bacterial pneumonia occurred in a convention of The American Legion at The Bellevue Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia. This pneumonia killed 34 people at the convention and later became known as Legionnaires' disease (Legionellosis). The bacterium that causes the illness was later named Legionella.

In 1988, after over 44 years of opposing U.S. Merchant seamen from receiving benefits under the G.I. Bill, they allowed Merchant seamen to join The American Legion.[91][92] This followed Merchant seamen being granted limited veterans status by the United States Secretary of the Air Force on January 19, 1988.[93]

After a 1989 U.S. Supreme Court decision (Texas v. Johnson), The American Legion launched and funded an unsuccessful campaign to win a constitutional amendment against harming the flag of the United States. The Legion formed the Citizens' Flag Honor Guard and it later became the Citizens Flag Alliance.[94]

1990s to present

In 1993, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts renamed a bridge in the city of Chicopee to the "American Legion Memorial Bridge".[95]

Also in 1993, two members of Garden City, Michigan American Legion Post 396 shared an idea that would bond motorcycle enthusiasts in the Legion from the idea of Chuck Dare and post commander Bill Kaledas, creating the American Legion Riders. Joined by 19 other founding members, the group soon found itself inundated with requests for information about the new group. As a source of information a website was set up, and it continues to be a source of information worldwide. By 2009, the American Legion Riders program had grown to over 1,000 chapters and 100,000 members in the United States and overseas.

In a letter to U.S. President Bill Clinton in May 1999, The American Legion urged the immediate withdrawal of U.S. troops from Operation Allied Force in Yugoslavia. The National Executive Committee of The American Legion met and adopted a resolution unanimously that stated, in part, that they would only support military operations if "Guidelines be established for the mission, including a clear exit strategy" and "That there be support of the mission by the U.S. Congress and the American people."[96]

In 2006, the Chairman of the House Veterans Affairs Committee, Steve Buyer (R-Ind.), announced that he planned to eliminate the annual congressional hearings for Veterans Service Organizations that was established by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. In response, National Commander of The American Legion Thomas L. Bock said, "I am extremely disappointed in Chairman Buyer's latest effort to ignore the Veterans Service Organizations. Eliminating annual hearings before a joint session of the Veterans Affairs Committees will lead to continued budgetary shortfalls for VA resulting in veterans being underserved."[97]

According to The American Legion, the ACLU has used the threat of attorney fees to intimidate cities, counties, school boards and other locally elected bodies into surrendering to its demands to remove religion from the public square.[98] As such The American Legion states that it "is leading a nationwide effort to combat the secular cleansing of our American heritage",[98] stating that the phrase "separation of church and state" is nowhere mentioned in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution[98] The American Legion released a document titled "In The Footsteps Of The Founders – A Guide To Defending American Values" to be available to the citizens of The United States of America.[98] The veteran's organization has done this to curtail religious-establishment cases against the Boy Scouts and the official display of the Ten Commandments and other religious symbols on public property,[98] in coordination with other Christian Dominionists.

In October 2011, National Commander Jimmie L Foster objected to courts allowing homosexuals to serve openly in the military.[99]

On March 25, 2014, The American Legion testified before Congress in favor of the bill "To amend title 38, United States Code, to reestablish the Professional Certification and Licensure Advisory Committee of the Department of Veterans Affairs (H.R. 2942; 113th Congress)." They argued that the legislation would "benefit service members, as well as those who eventually employ veterans in civilian work-force easing the placement of qualified veterans in civilian careers, and matching civilian employers with skilled veteran employees."[100] The American Legion argued that this committee was important to the process of matching military certifications with their corresponding civilian ones, smoothing that transition for veterans, and that the committee provided much needed expertise on these matters to the VA. The American Legion said that "there is a definite need to resume this independent body with expertise in matters relating to licensing and credentialing which can present new solutions to VA's senior leadership and congressional members as well as other stakeholders."[100]

Also in 2014, Verna L. Jones was appointed as the first female executive director of The American Legion.[101]

Programs

At the state level, The American Legion is organized into "departments", which run annual civic training events for high school juniors called Boys State. Two members from each Boys State are selected for Boys Nation. The American Legion Auxiliary runs Girls State and Girls Nation. In addition to Boys State, The American Legion features numerous programs including American Legion Baseball, Scouting, Oratorical Contests, Junior Shooting Sports, Youth Alumni, Sons of the American Legion, American Legion Riders, and Scholarships at every level of the organization.

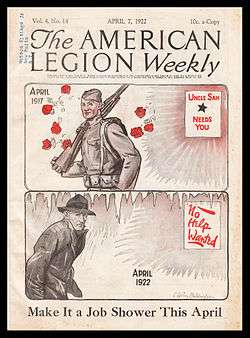

Publications

The organization's official publication in its initial phase was a magazine called The American Legion Weekly, launched on July 4, 1919.[102] This publication switched its frequency and renamed itself The American Legion Monthly in 1926.[103] In 1936 the publication's name and volume numbering system changed again, this time to American Legion Magazine.[104]

Organization

National

The main American Legion Headquarters is located on the Indiana World War Memorial Plaza in Indianapolis. It is the primary office for the National Commander and also houses the historical archives, library, Membership, Internal Affairs, Public Relations, and the Magazine editorial offices.[105] The Legion also owns a building in Washington D.C. that contains many of the operation offices such as Economics, Legislative, Veterans Affairs, Foreign Relations, National Security, and Media Relations. A National Officer or National Executive Committee Representative is distinguished by a red garrison cap with gold piping.

Departments

The head department for each state is located in that states capital. There is a total of 55 lodges; one for each of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, France, Mexico, and the Philippines. The departments located overseas are intended to allow active duty military stationed and veterans living overseas to be actively involved with The American Legion similar to as if they were back in the United States. The main Department of France consists of 29 posts located in 10 European counties, the Department of Mexico consists of 22 posts located in Central America, and the Department of Philippines covers Asia and the Pacific Islands. A department officer or department executive committee representative is distinguished by a white garrison cap with gold piping.

Districts

Each Department is divided into Divisions and/or Districts. Each District oversees several Posts, generally about 20, to help each smaller group have a larger voice. Divisions are even larger groups of about four or more Districts. The main purpose of these "larger" groups (Districts and Divisions) is to allow one or two delegates to represent an area at conferences, conventions, and other gatherings, where large numbers of Legionnaires may not be able to attend. A District Commander is distinguished by a navy blue garrison cap with a white crown and gold piping.

Counties

Each U.S. county comprises several Posts and oversees their operations, led by a County Council of elected officers. The County Commander performs annual inspections of the Posts within their jurisdiction and reports the findings to both the District and the Department level. A County Commander is distinguished by a navy blue garrison cap with white piping.

Posts

The Post is the basic unit of the Legion and usually represents a small geographic area such as a single town or part of a county. There are roughly 14,900 posts in the United States. The Post is used for formal business such as meetings and a coordination point for community service projects. Often the Post will host community events such as bingo, Hunter breakfasts, holiday celebrations, and available to the community, churches in time of need. It is also not uncommon for the Post to contain a bar open during limited hours. A Post member is distinguished by a navy blue garrison cap with gold piping.

Notable members

Notable members of The American Legion have included:[106][107][108]

-

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, Medal of Honor recipient

-

General George Patton, Jr., Two-time Distinguished Service Cross recipient

-

Sergeant Alvin York, Medal of Honor recipient

-

Humphrey Bogart, Academy Award winner

-

Clark Gable, Academy Award winner

List of Past National Commanders

- Franklin D'Olier, Pennsylvania, 1919–1920

- Frederic W. Galbraith, Jr., Ohio, 1920–1921

- John G. Emery, Michigan, June 14, 1921 – November 2, 1921

- Hanford MacNider, Iowa, 1921–1922

- Alvin M. Owsley, Texas, 1922–1923

- John R. Quinn, California, 1923–1924

- James A. Drain, Washington, 1924–1925

- John R. McQuigg, Ohio, 1925–1926

- Howard P. Savage, Illinois, 1926–1927

- Edward E. Spafford, New York, 1927–1928

- Paul V. McNutt, Indiana, 1928–1929

- O. L. Bodenhamer, Arkansas, 1929–1930

- Ralph T. O'Neil, Kansas, 1930–1931

- Henry L. Stevens, Jr., North Carolina, 1931–1932

- Louis A. Johnson, West Virginia, 1932–1933

- Edward A. Hayes, Illinois, 1933–1934

- Frank N. Belgrano, California, 1934–1935

- Ray Murphy, Iowa, 1935–1936

- Harry W. Colmery, Kansas, 1936–1937

- Daniel J. Doherty, Massachusetts, 1937–1938

- Stephen F. Chadwick, Washington, 1938–1939

- Raymond J. Kelly, Michigan, 1939–1940

- Milo J. Warner, Ohio, 1940–1941

- Lynn U. Stambaugh, North Dakota, 1941–1942

- Roane Waring, Tennessee, 1942–1943

- Warren H. Atherton, California, 1943–1944

- Edward N. Scheiberling, New York, 1944–1945

- John Stelle, Illinois, 1945–1946

- Paul H. Griffith, Pennsylvania, 1946–1947

- James F. O'Neal, New Hampshire, 1947–1948

- S. Perry Brown, Texas, 1948–1949

- George N. Craig, Indiana, 1949–1950

- Erle Cocke, Jr., Georgia, 1950–1951

- Donald R. Wilson, West Virginia, 1951–1952

- Lewis K. Gough, California, 1952–1953

- Arthur J. Connell, Connecticut, 1953–1954

- Seaborn P. Collins, New Mexico, 1954–1955

- J. Addington Wagner, Michigan, 1955–1956

- Dan Daniel, Virginia, 1956–1957

- John S. Gleason, Jr., Illinois, 1957–1958

- Preston J. Moore, Oklahoma, 1958–1959

- Martin B. McKneally, New York, 1959–1960

- William R. Burke, California, 1960–1961

- Charles L. Bacon, Missouri, 1961–1962

- James E. Powers, Georgia, 1962–1963

- Daniel F. Foley, Minnesota, 1963–1964

- Donald E. Johnson, Iowa, 1964–1965

- L. Eldon James, Virginia, 1965–1966

- John E. Davis, North Dakota, 1966–1967

- William E. Galbraith, Nebraska, 1967–1968

- William C. Doyle, New Jersey, 1968–1969

- J. Milton Patrick, Oklahoma, 1969–1970

- Alfred P. Chamie, California, 1970–1971

- John H. Geiger, Illinois, 1971–1972

- Joe L. Matthews, Texas, 1972–1973

- Robert E. L. Eaton, Maryland, 1972–1973

- James M. Wagonseller, Ohio, 1974–1975

- Harry G. Wiles, Kansas, 1975–1976

- William J. Rogers, Maine, 1976–1977

- Robert C. Smith, Louisiana, 1977–1978

- John M. Carey, Michigan, 1978–1979

- Frank I. Hamilton, Indiana, 1979–1980

- Michael J. Kogutek, New York, 1980–1981

- Jack W. Flynt, Texas, 1981–1982

- Al Keller, Jr., Illinois, 1982–1983

- Keith A. Kreul, Wisconsin, 1983–1984

- Clarence M. Bacon, Maryland, 1984–1985

- Dale L. Renaud, Iowa, 1985–1986

- James P. Dean, Mississippi, 1986–1987

- John P. Comer, Massachusetts, 1987–1988

- H. F. Gierke III, North Dakota, 1988–1989

- Miles S. Epling, West Virginia, 1989–1990

- Robert S. Turner, Georgia, 1990–1991

- Dominic D. DiFrancesco, Pennsylvania, 1991–1992

- Roger A. Munson, Ohio, 1992–1993

- Bruce Thiesen, California, 1993–1994

- William M. Detweiler, Louisiana, 1994–1995

- Daniel A. Ludwig, Minnesota, 1995–1996

- Joseph J. Frank, Missouri, 1996–1997

- Anthony G. Jordan, Maine, 1997–1998

- Harold L. Miller, Virginia, 1998–1999

- Alan G. Lance, Sr., Idaho, 1999–2000

- Ray G. Smith, North Carolina, 2000–2001

- Richard J. Santos, Maryland, 2001–2002

- Ronald F. Conley, Pennsylvania, 2002–2003

- John A. Brieden III, Texas, 2003–2004

- Thomas P. Cadmus, Michigan, 2004–2005

- Thomas L. Bock, Colorado, 2005–2006

- Paul A. Morin, Massachusetts, 2006–2007

- Martin F. Conatser, Illinois, 2007–2008

- David K. Rehbein, Iowa, 2008–2009

- Clarence E. Hill, Florida, 2009–2010

- Jimmie L. Foster, Alaska, 2010–2011

- Fang A. Wong, New York, 2011–2012

- James E. Koutz, Indiana, 2012–2013

- Daniel Dellinger, Virginia, 2013–2014

- Michael D. Helm, Nebraska, 2014–2015

- Dale Barnett, Georgia, 2015–2016

List of Past National Commanders by Vote of National Conventions

- Henry D. Lindsley, Texas, 1919

- Milton J. Foreman, Illinois, 1921

- Bennett Champ Clark, Missouri, 1926

- Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., New York, 1949

- Eric Fisher Wood, Pennsylvania, 1955

- Thomas W. Miller, Nevada, 1968

- Maurice Stember, New York, 1975

- Hamilton Fish III, New York, 1979

- E. Roy Stone, Jr., South Carolina, 1987[109][110]

- Robert W. Spanogle, Michigan, 2008

List of Honorary National Commanders

See also

- Armed Forces Day

- Flag Day

- Memorial Day

- Memorial Poppy

- Royal British Legion

- Royal Canadian Legion

- South African Legion

- SS American Legion

- Veterans Day

Notes

- ↑ Wheat 1919, p. 18.

- ↑ "American Legion Day". The American Legion Magazine. Indianapolis, Indiana. September 2016. p. 8. ISSN 0886-1234.

- ↑ "Membership in The American Legion". The American Legion Magazine. Indianapolis, Indiana. September 2016. p. 5. ISSN 0886-1234.

- ↑ Carney, Timothy. "Changing of the Guard". Philanthropy Roundtable. Philanthropy.

- 1 2 3 Marquis James, A History of The American Legion. New York: William Green, 1923; p. 77.

- 1 2 Rumer 1990, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Bleiler, Richard. "A History of Adventure Magazine". Philsp. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- 1 2 (via Google News)"Patriotic Founders Invite". The Spokesman-Review. Cowles Publishing Company. July 25, 1915. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ↑ (via Google News)Doenecke, Justus D. (2011). Nothing Less Than War: A New History of America's Entry into World War I. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3002-6.

- ↑ "American Legion of Honor Doing Big Work". The Harvard Crimson. October 1, 1915. Retrieved March 13, 2016./

- ↑ (via Google News)"Nation gets Roster of American Legion". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. December 26, 1916. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ↑ (via Google News)"The Passing of the American Legion". The Day. The Day Publishing Company. December 26, 1916. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- 1 2 3 James, A History of The American Legion, p. 14.

- 1 2 James, A History of The American Legion, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 James, A History of The American Legion, pg. 16.

- 1 2 Rumer 1990, p. 13.

- ↑ James, A History of The American Legion, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ James, A History of The American Legion, pp. 17–18.

- 1 2 James, A History of The American Legion, p. 18.

- ↑ James, A History of The American Legion, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ James, A History of The American Legion, p. 20.

- ↑ Rumer 1990, p. 15.

- 1 2 Rumer 1990, p. 16.

- ↑ "An interpretative sign exists at the site, in 2009". warmonument.blogspot.com. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- 1 2 "History Part I – 1919–1959". chinapost1.org. July 1, 1988. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- 1 2 "China Post One". chinapost1.org. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ Wheat 1919, p. 19.

- ↑ Rumer 1990, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Rumer 1990, p. 19.

- 1 2 Rumer 1990, p. 21.

- ↑ Rumer 1990, p. 23.

- ↑ Rumer 1990, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 Rumer 1990, p. 25.

- ↑ Rumer 1990, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Rumer 1990, p. 26.

- ↑ Rumer 1990, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ James, A History of The American Legion, pg. 44.

- ↑ James, A History of The American Legion, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ James, A History of The American Legion, pp. 47–48.

- 1 2 3 4 William Pencak, For God and Country: The American Legion, 1919–1941. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1989; p. 58.

- 1 2 Pencak, For God and Country, p. 59.

- ↑ The words are those of Dorothy R. Harper, "Hawaii – Department History", quoted in Pencak, For God and Country, p. 59.

- ↑ Wheat 1919, p. 193.

- ↑ Pencak, For God and Country, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Pencak, For God and Country, pg. 60.

- ↑ Jones, A History of The American Legion, p. 349.

- ↑ Richard Seely Jones, A History of The American Legion. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1946; p. 44.

- ↑ Quoted in Jones, A History of The American Legion, p. 49.

- ↑ Jones, A History of The American Legion, p. 45.

- ↑ Jones, A History of The American Legion, p. 46.

- 1 2 Jones, A History of The American Legion, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 4 Jones, A History of The American Legion, p. 48.

- ↑ Jones, A History of The American Legion, p. 85.

- 1 2 Jones, A History of The American Legion, p. 86.

- ↑ "Department History". amerlegiondeptfrance.org. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Tom Copeland, The Centralia Tragedy of 1919: Elmer Smith and the Wobblies. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1993; p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Copeland, The Centralia Tragedy of 1919, p. 51.

- ↑ Copeland, The Centralia Tragedy of 1919, pp. 51–52.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Copeland, The Centralia Massacre of 1919, p. 52.

- ↑ Copeland, The Centralia Tragedy of 1919, p. 53.

- ↑ Copeland, The Centralia Tragedy, pp. 53–54.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Copeland, The Centralia Tragedy of 1919, p. 54.

- 1 2 Copeland, The Centralia Tragedy of 1919, p. 55.

- 1 2 Copeland, The Centralia Tragedy of 1919, p. 59.

- ↑ Copeland, The Centralia Tragedy of 1919, pp. 65, 82–83.

- ↑ Heale, p. 82

- ↑ Heale, p. 86

- ↑ Heale, p. 85

- 1 2 3 Ceplair, p. 38

- ↑ American Red Cross, "World War Adjusted Compensation Act", updated: July 19, 1926, pp. 363–74, Available online", accessed January 10, 2011

- ↑ William Pencak, For God And Country: The American Legion, 1919–1941 Northeastern University Press, 1989; p. 21.

- 1 2 Alec Campbell, "Where Do All the Soldiers Go?: Veterans and the Politics of Demobilization", in Diane E. Davis, Anthony W. Pereira, eds., Irregular Armed Forces and their Role in Politics and State Formation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003; pp. 110–11.

- 1 2 "Information on The American Legion Memorial Bridge". Michigan Department of Transportation Web Site. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ "History of Sons of The American Legion". legion.org/sons. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ Stephen R. Ortiz, "The 'New Deal' for Veterans: The Economy Act, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and the Origins of the New Deal", Journal of Military History, vol. 70 (2006), pp. 417–37

- ↑ "Butler for Bonus out of Wall Street". New York Times. December 10, 1933. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

- ↑ George Wolfskill, The Revolt of the Conservatives: A History of the American Liberty League, 1934–1940 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1962), pp. 81–101. For an extended account of the conspiracy theory, see Jules Archer, The Plot to Seize the White House (NY: Hawthorn Books, 1973)

- ↑ Carelton, Don. Red Scare: Right-Wing Hysteria, Fifties Fanaticism and their Legacy in Texas. 3057: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292758551.

- ↑ Harper, Sue; Porter, Vincent (2003). British Cinema of the 1950s: The Decline of Deference. Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780198159353.

- ↑ Sydney E. Ahlstrom, David D. Hall (2004). A Religious History of the American People. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300100129. Retrieved December 31, 2007.; Gastón Espinosa, ed., Religion and the American Presidency: George Washington to George W. Bush (NY: Columbia University Press, 2009) pages=278–79

- ↑ "'Back to God' Drive Enlists President". New York Times. February 2, 1953. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ↑ Heale, p. 111

- ↑ Ceplair, p. 120

- ↑ Ceplair, p. 121

- ↑ Heale, p. 173

- ↑ Heale, p. 187

- ↑ Ceplair, pp. 28, 33, 38, 121, 123, 198–200

- ↑ Ceplair, p. 241

- ↑ William A. Donohue, The Politics of the American Civil Liberties Union (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1985), p. 182

- ↑ "Cabin John Bridge Given a New Name", Washington Post, Times Herald (Washington, D.C.): City Life Section, May 31, 1969

- ↑ The Boston Globe (December 9, 1987). "American Legion Still Opposes Veteran Status For Merchant Seamen". The Journal of Commerce. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ↑ Brian Herbert, The Forgotten Heroes: The Heroic Story of the United States Merchant Marine (New York: Forge, 2005), p. 201

- ↑ Christine Scott; Douglas Reid Weimer, Veterans Benefits: Merchant Seamen (Washington, DC, Congressional Research Service, May 8, 2007), p. 1

- ↑ "Citizens Flag Alliance". sourcewatch.org. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Archives" (PDF). Library of the State of Massachusetts. Retrieved June 11, 2007.

- ↑ "American Legion Urges Withdrawal of Troops from Yugoslavia". C-SPAN Video Library. May 18, 1999. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Battle between Legion, Buyer Rages On". Army Times. June 12, 2006. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Legion campaign backs anti-ACLU bill" (PDF). American Legion. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

The American Legion family is involved in the effort to have the Veterans' Memorials, Boy Scouts, Public Seals, and Other Public Expressions of Religion Protection Act of 2007 (PERA) passed by Congress because of the clear need to stop the ACLU and other organizations from making enormous profits in lawsuits under the Establishment Clause attacking the Boy Scouts, the public display of the Ten Commandments, the Pledge of Allegiance, and other symbols of our American religious history and heritage, including religious symbols at veterans memorials. Pulling the rug out from under the funding source against American values should significantly curtail the current proliferation of attacks.

- ↑ Foster, Jimmie (October 28, 2011). "Court oversteps its bounds on DADT". American Legion Magazine. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- 1 2 Gonzalez, Steve (March 25, 2014). "Witness Testimony of Mr. Steve Gonzalez, Assistant Director, National Economic Commission, The American Legion". House Committee on Veterans Affairs. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ↑ "American Legion Appoints First Female Executive Director". Military.com. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ The American Legion Weekly, OCLC 1480272. Master negative microfilm held by University Microfilms, now part of ProQuest.

- ↑ The American Legion Monthly, OCLC 1781656.

- ↑ American Legion Magazine, OCLC 1480271.

- ↑ American Legion: "Office Locations, accessed December 30, 2010

- ↑ Wheat 1919, p. 263.

- ↑ Ford 1979, p. 62.

- ↑ York 1930, pp. 290–291.

- 1 2 American Legion 1958, p. 4.

- ↑ Rumer 1990, p. 549.

References

- "American Legion 40th National Convention: official program [1958]". American Legion. 1958.

- Ceplair, Larry (2011). Anti-communism in Twentieth-century America: A Critical History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440800474. OCLC 712115063.

- Ford, Gerald R. (1979). A Time To Heal: The Autobiography of Gerald R. Ford. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-011297-2. OCLC 4835213.

- Heale, M.J. (1990). American Anticommunism: Combating the Enemy Within, 1830-1970. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801840500. OCLC 21483404.

- Rumer, Thomas A. (1990). The American Legion: An Official History, 1919–1989. New York: M Evans & Co. ISBN 978-0871316226. OCLC 22207881.

- Wheat, George Seay (1919). "The Story of The American Legion". The Birth of the Legion. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-1104507251.

- York, Alvin C. (1930). Skeyhill, Tom, ed. His Own Life Story And War Diary. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company.

Further reading

- Littlewood, Thomas B. (2004). Soldiers Back Home: The American Legion in Illinois, 1919–1939. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 080932587X. OCLC 54461886.

- Moley, Raymond (1966). The American Legion Story. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce. ISBN 9780809325870. OCLC 712139.

- Pencak, William (1989). For God & Country: The American Legion, 1919–1941. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1555530508. OCLC 18682663.

- Spencer, Dewey, ed. (1979). History of The American Legion, Department of Arkansas, 1919–1979. Little Rock, Arkansas.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to American Legion. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article American Legion. |

- Official website

- American Legion, Dept. of Washington records, 1919-1920 at the University of Washington Libraries

- "American Legion photographs". University of Missouri–St. Louis.

- American Legion Politician members at The Political Graveyard

- Federal Bureau of Investigation files relating to The American Legion at the Internet Archive

- World War I Centennial Commission at the United States Foundation for the Commemoration of the World Wars