Arthropods in culture

.jpg)

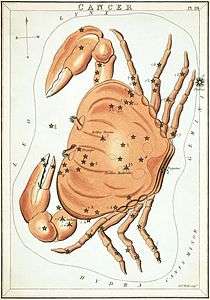

Arthropods play many roles in culture. Many of these concern insects, which are important both economically and symbolically, from the work of honeybees to the scarabs of Ancient Egypt. Other arthropods with cultural significance include crustaceans such as crabs, lobsters, and crayfish, which are popular subjects in art, especially still lifes, and arachnids such as spiders and scorpions, whose venom has medical applications. The crab and the scorpion are astrological signs of the zodiac.

Insects

Insects play many roles in culture including their direct use as food,[1][2][3] in medicine,[2][4][5][6][7][8][9] for dyestuffs,[10] and in science, where the common fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster serves as a model organism for work in genetics and developmental biology.[11]

Indirect uses include appearances in mythology,[12]:9[13] in religion,[14][15] in biomimicry,[16][17][18][19][20] in art,[21][22][23][24][25][26] in literature and film,[27] and in music.[28][29][30]

Crustaceans

Crustaceans are an important source of food, providing nearly 10,700,000 tons in 2007; the vast majority of this output is of decapods: crabs, lobsters, shrimps, crayfish, and prawns. Over 60% by weight of all crustaceans caught for consumption are shrimp and prawns, and nearly 80% is produced in Asia, with China alone producing nearly half the world's total. Non-decapod crustaceans are not widely consumed, with only 118,000 tons of krill being caught, despite krill having one of the greatest biomasses on the planet.[31][32]

Crab

Crabs make up 20% of all marine crustaceans caught, farmed, and consumed worldwide, amounting to 1.5 million tonnes annually. One species, Portunus trituberculatus, accounts for one-fifth of that total. Other commercially important taxa include Portunus pelagicus, several species in the genus Chionoecetes, the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus), Charybdis spp., Cancer pagurus, the Dungeness crab (Metacarcinus magister), and Scylla serrata, each of which yields more than 20,000 tonnes annually.[33]

Both the constellation Cancer and the astrological sign Cancer are named after the crab, and depicted as a crab. William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse drew the Crab Nebula in 1848 and noticed its similarity to the animal; the Crab pulsar lies at the centre of the nebula.[34] The Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped nature, especially the sea,[35] and often depicted crabs in their art.[36] In Greek mythology, Karkinos was a crab that came to the aid of the Lernaean Hydra as it battled Heracles. One of Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories, The Crab that Played with the Sea, tells the story of a gigantic crab who made the waters of the sea go up and down, like the tides.[37]

Lobster

Lobsters are caught using baited, one-way traps with a colour-coded marker buoy to mark cages. Lobster is fished in water between 2 and 900 metres (1 and 500 fathoms), although some lobsters live at 3,700 metres (2,000 fathoms). Cages are of plastic-coated galvanised steel or wood. A lobster fisher may tend as many as 2,000 traps. Around 2000, owing to overfishing and high demand, lobster aquaculture expanded.[38] As of 2008, no lobster aquaculture operation had achieved commercial success, mainly because lobsters eat each other (cannibalism) and the growth of the species is slow.[39]

The "Lobster Quadrille", also known as "The Mock Turtle's Song", is a song recited by the Mock Turtle in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, chapters 9 and 10, accompanied by a dance.[40]

The surrealist artist Salvador Dali created a sculpture called Lobster Telephone with the crustacean in place of the traditional handset, resting in the cradle above the dial.[41]

Arachnids

Spider

Spider venoms may be a less polluting alternative to conventional pesticides, as they are deadly to insects but the great majority are harmless to vertebrates. Australian funnel web spiders are a promising source, as most of the world's insect pests have had no opportunity to develop any immunity to their venom, and funnel web spiders thrive in captivity and are easy to "milk". It may be possible to target specific pests by engineering genes for the production of spider toxins into viruses that infect species such as cotton bollworms.[42]

The Ch'ol Maya use a beverage created from the tarantula species Brachypelma vagans for the treatment of a condition they term 'tarantula wind', the symptoms of which include chest pain, asthma and coughing.[43]

Possible medical uses for spider venoms are being investigated, for the treatment of cardiac arrhythmia,[44] Alzheimer's disease,[45] strokes,[46] and erectile dysfunction.[47] The peptide GsMtx-4, found in the venom of Brachypelma vagans, is being researched for possible use in cardiac arrhythmia, muscular dystrophy or glioma.[48] Because spider silk is both light and strong, attempts are being made to produce it in goats' milk and in the leaves of plants, by means of genetic engineering.[49][50]

Spiders can also be used as food. Cooked tarantula spiders are considered a delicacy in Cambodia,[51] and by the Piaroa Indians of southern Venezuela – provided the highly irritant hairs, the spiders' main defence system, are removed first.[52]

Arachnophobia is the abnormal fear of spiders. It is a common phobia,[53][54] and some statistics show that 50% of women and 10% of men show symptoms.[55] It may be an exaggerated form of an instinctive response that helped early humans to survive,[56] or a cultural phenomenon that is most common in predominantly European societies.[57]

Spiders have been the focus of stories and mythologies in many cultures for centuries.[58] They have symbolized patience due to their hunting technique of setting webs and waiting for prey, as well as mischief and malice due to their venomous bites.[59] The Italian tarantella is a dance supposedly to rid the young woman of the lustful effects of a bite by the tarantula wolf spider, Lycosa tarantula.[60]

Web-spinning caused the association of the spider with creation myths, as they seem to produce their own worlds.[61] Dreamcatchers are depictions of spiderwebs. The Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped nature.[62] They placed emphasis on animals and often depicted spiders in their art.[63]

Scorpion

One of earliest occurrences of the scorpion in culture is its inclusion, as the astrological sign Scorpio, in the twelve signs of the Zodiac by Babylonian astronomers during the Chaldean period, around 600 BC.[64]

In South Africa and South Asia, the scorpion is a significant animal culturally, appearing as a motif in art, especially in Islamic art in the Middle East.[65] A scorpion motif is often woven into Turkish kilim flatweave carpets, for protection from their sting.[66] The scorpion is perceived both as an embodiment of evil and a protective force that counters evil, such as a dervish's powers to combat evil.[65] In another context, the scorpion portrays human sexuality.[65] Scorpions are used in folk medicine in South Asia especially in antidotes for scorpion stings.[65]

In ancient Egypt the goddess Serket was often depicted as a scorpion, one of several goddesses who protected the Pharaoh.[67]

The Surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel makes notable symbolic use of scorpions in his 1930 classic L'Age d'or (The Golden Age).[68]

In art

-

Still life with silver-gilt tazza (and crayfish), Clara Peeters, c. 1600

-

Still Life with Crab, Shrimps and Lobster, Clara Peeters, c. 1600

-

Fish, oysters, a crab and a lobster with cats..., Jan Fyt, c. 1650

-

Pronk Still life with lobster, Jasper Geeraerts, 1650–1654

-

Le Crabe by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1869

-

The Lobster by Samuel Peploe, c. 1903

-

Illustration from The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley, illustrated by Warwick Goble (d. 1943)

References

- ↑ Meyer-Rochow V.B., Nonaka K., Boulidam S (2008) More feared than revered: Insects and their impacts on human societies (with specific data on the importance of entomophagy in a Laotian setting. Entomologie Heute 20: 3-25

- 1 2 Chakravorty, J., Ghosh, S., and V.B. Meyer-Rochow. (2011). Practices of entomophagy and entomotherapy by members of the Nyishi and Galo tribes, two ethnic groups of the state of Arunachal Pradesh (North-East India). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 7(5)

- ↑ Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno (1975). "Can insects help to ease the problem of world food shortage?". ANZAAS Journal: "Search". 6(7):: 261–262.

- ↑ Ratcliffe, N.A. et al. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 41 (2011) 747e769

- ↑ Yang, X., Hu, K., Yan, G., et al., 2000. Fibrinogenolytic components in Tabanid, an ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine and their properties. J. Southwest Agric. Univ. 22, 173e176 (Chinese).

- ↑ Sun, Xinjuan; Jiang, Kechun; Chen, Jingan; Wu, Liang; Lu, Hui; Wang, Aiping; Wang, Jianming (2014). "A systematic review of maggot debridement therapy for chronically infected wounds and ulcers". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 25: 32–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.03.1397. PMID 24841930.

- ↑ Feng, Y., Zhao, M., He, Z., Chen, Z., and L. Sun. (2009). Research and utilization of medicinal insects in China. Entomological Research, 39: 313-316.

- ↑ Srivastava, S.K., Babu, N., and H. Pandey. (2009). Traditional insect bioprospecting--As human food and medicine. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, 8(4): 485-494.

- ↑ Ramos-Elorduy de Concini, J. and J.M. Pino Moreno. (1988). The utilization of insects in the empirical medicine of ancient Mexicans. Journal of Ethnobiology, 8(2), 195-202.

- ↑ "Cochineal and Carmine". Major colourants and dyestuffs, mainly produced in horticultural systems. FAO. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ↑ Pierce, BA (2006). Genetics: A Conceptual Approach (2nd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. p. 87. ISBN 0-7167-8881-0.

- ↑ Gullan, P.J.; Cranston, P.S. (2005). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology (3rd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1113-5.

- ↑ Gullan, P. J.; Cranston, P. S. (2009). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 9–13. ISBN 978-1-4051-4457-5.

- ↑ William Balée (2000), "Antiquity of Traditional Ethnobiological Knowledge in Amazonia: a Tupí–Guaraní Family and Time" Ethnohistory 47(2):399-422.

- ↑ Groark, Kevin. Taxonomic Identity of "Hallucinogenic" Harvester Ant (Pogonomyrmex californicus) Confirmed. 2001. Journal of Ethnobiology 21(2):133-144

- ↑ "Biomimetic Building Uses Termite Mound As Model". Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ↑ "Termite research". esf.edu. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ↑ Pappagallo, Linda. "Termite Mounds Inspire Energy Neutral Buildings". Green Prophet. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ↑ "Namib Desert beetle inspires self-filling water bottle". BBC. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ Trivedi, Bijal P. "Beetle's Shell Offers Clues to Harvesting Water in the Desert". National Geographic Today. Retrieved November 1, 2001.

- ↑ Gough, Andrew. "The Bee Part 2 Beewildered". Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ↑ "A Beetle-Wing Tea-Cosy". Hampshire Cultural Trust. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ↑ Rivers, Victoria. "Beetles in Textiles". Cultural Entomology Digest February. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ↑ Nabokov, Vladimir (1989). Speak, Memory. New York: Vintage International. p. 129.

- ↑ French, Anneka. "Stirring the Swarm". Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ "Stirring the Swarm". Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ "Ladybug Ladybug (1963)". Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ↑ "Rimsky-Korsakov - The Flight of the Bumblebee (Homeschool Music Appreciation)". Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ "David Rothenberg: "Bug Music: How Insects Gave Us Rhythm and Noise"". The Diana Rehm Show. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ "From the Diary of a Fly, for piano (Mikrokosmos Vol. 6/142), Sz.107/6/142, BB 105/142". Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ "FIGIS: Global Production Statistics 1950–2007". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ↑ Steven Nicol; Yoshinari Endo (1997). Krill Fisheries of the World. Fisheries Technical Paper. 367. Food and Agriculture Organization. ISBN 978-92-5-104012-6.

- ↑ "Global Capture Production 1950-2004". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved August 26, 2006.

- ↑ B. B. Rossi (1969). The Crab Nebula: Ancient History and Recent Discoveries. Center for Space Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. CSR-P-69-27.

- ↑ Elizabeth Benson (1972). The Mochica: A Culture of Peru. New York, NY: Praeger Press. ISBN 978-0-500-72001-1.

- ↑ Katherine Berrin; Larco Museum (1997). The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-500-01802-6.

- ↑ Kipling, Rudyard (1902). "The Crab that Played with the Sea". Just So Stories. Macmillan.

- ↑ Asbjørn Drengstig; Tormod Drengstig & Tore S. Kristiansen. "Recent development on lobster farming in Norway – prospects and possibilities". UWPhoto ANS.

- ↑ "Riddles, Trivia and More". Gulf of Maine Research Institute. February 24, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ↑ "The Lobster-quadrille". The LIterature Network. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ↑ Lobster Telephone in the collection of Tate Liverpool, London. Accessed 27-01-2010.

- ↑ "Spider Venom Could Yield Eco-Friendly Insecticides". National Science Foundation (USA). Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ↑ Salima Machkour M'Rabet; Yann Hénaut; Peter Winterton & Roberto Rojo (2011). "A case of zootherapy with the tarantula Brachypelma vagans Ausserer, 1875 in traditional medicine of the Chol Mayan ethnic group in Mexico". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine.

- ↑ Novak, K. (2001). "Spider venom helps hearts keep their rhythm". Nature Medicine. 7 (155): 155. doi:10.1038/84588. PMID 11175840.

- ↑ Lewis, R. J. & Garcia, M. L. (2003). "Therapeutic potential of venom peptides" (PDF). Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2 (10): 790–802. doi:10.1038/nrd1197. PMID 14526382.

- ↑ Bogin, O. (Spring 2005). "Venom Peptides and their Mimetics as Potential Drugs" (PDF). Modulator (19).

- ↑ Andrade E.; Villanova F.; Borra P.; Leite, Katia; Troncone, Lanfranco; Cortez, Italo; Messina, Leonardo; Paranhos, Mario; Claro, Joaquim; Srougi, Miguel (2008). "Penile erection induced in vivo by a purified toxin from the Brazilian spider Phoneutria nigriventer". British Journal of Urology International. 102 (7): 835–7. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07762.x. PMID 18537953.

- ↑ Salima Machkour-M'Rabet; Yann Hénaut; Peter Winterton & Roberto Rojo (2011). "A case of zootherapy with the tarantula Brachypelma vagans Ausserer, 1875 in traditional medicine of the Chol Mayan ethnic group in Mexico". Journal of ethnobiology and ethno medicine.

- ↑ Hinman, M. B.; Jones J. A. & Lewis, R. W. (2000). "Synthetic spider silk: a modular fiber" (PDF). Trends in Biotechnology. 18 (9): 374–9. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(00)01481-5. PMID 10942961.

- ↑ Menassa, R.; Zhu, H.; Karatzas, C. N.; Lazaris, A.; Richman, A.; Brandle, J. (2004). "Spider dragline silk proteins in transgenic tobacco leaves: accumulation and field production". Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2 (5): 431–8. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7652.2004.00087.x. PMID 17168889.

- ↑ Ray, N. (2002). Lonely Planet Cambodia. Lonely Planet Publications. p. 308. ISBN 1-74059-111-9.

- ↑ Weil, C. (2006). Fierce Food. Plume. ISBN 0-452-28700-6. Retrieved 2008-10-03.

- ↑ "A Common Phobia". phobias-help.com. Archived from the original on 2009-08-02. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

There are many common phobias, but surprisingly, the most common phobia is arachnophobia.

- ↑ Fritscher, Lisa (2009-06-03). "Spider Fears or Arachnophobia". Phobias. About.com. Archived from the original on 2009-08-02. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

Arachnophobia, or fear of spiders, is one of the most common specific phobias.

- ↑ "The 10 Most Common Phobias — Did You Know?". 10 Most Common Phobias. Archived from the original on 2009-08-02. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

Probably the most recognized of the 10 most common phobias, arachnophobia is the fear of spiders. The statistics clearly show that more than 50% of women and 10% of men show signs of this leader on the 10 most common phobias list.

- ↑ Friedenberg, J. & Silverman, G. (2005). Cognitive Science: An Introduction to the Study of Mind. SAGE. pp. 244–245. ISBN 1-4129-2568-1.

- ↑ Davey, G. C. L. (1994). "The "Disgusting" Spider: The Role of Disease and Illness in the Perpetuation of Fear of Spiders". Society and Animals. 2 (1): 17–25. doi:10.1163/156853094X00045.

- ↑ De Vos, Gail (1996). Tales, Rumors, and Gossip: Exploring Contemporary Folk Literature in Grades 7–12. Libraries Unlimited. p. 186. ISBN 1-56308-190-3.

- ↑ Garai, Jana (1973). The Book of Symbols. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-21773-9.

- ↑ Ettlinger, Ellen (1965). Review of "La Tarantella Napoletana" by Renato Penna (Rivista di Etnografia), Man, Vol. 65. (Sep. – Oct., 1965), p. 176.

- ↑ De Laguna, Frederica (2002). American Anthropology: Papers from the American Anthropologist. University of Nebraska Press. p. 455. ISBN 0-8032-8280-X.

- ↑ Benson, Elizabeth. The Mochica: A Culture of Peru. New York: Praeger Press. 1972.

- ↑ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ↑ Gary A. Polis (1990). The Biology of Scorpions. Stanford University Press. p. 462. ISBN 978-0-8047-1249-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Jürgen Wasim Frembgen (2004). "The scorpion in Muslim folklore" (PDF). Asian Folklore Studies. 63 (1): 95–123.

- ↑ Erbek, Güran (1998). Kilim Catalogue No. 1. May Selçuk A. S. Edition=1st.

- ↑ Mark, Joshua J. "Serket". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ↑ Allen S. Weiss (1996). "Between the sign of the scorpion and the sign of the cross: L'Age d'or". In Rudolf E. Kuenzli. Dada and Surrealist Film. MIT Press. pp. 159–175. ISBN 978-0-262-61121-3.