Insects in literature

Insects have appeared in literature from classical times to the present day, an aspect of the role played by insects in culture. Among the insects treated are the ant, bee, butterfly, dragonfly, fly, grasshopper and locust, horsefly and wasp.

Overview

Insects play important roles in around one hundred novels and a hundred short stories in English literature. They are used to portray both positive and negative qualities, more usually negative, including entrapment, stinging, being rapacious, and swarming. They are common in fantasy and especially in science fiction, often as the earthly or alien villains. Detective novels sometimes use insects as unexpected murder weapons. A fly on the wall is used as a voyeur to tell erotic stories in R. Chopping's The Fly, and the anonymous Autobiography of a Flea. Franz Kafka made use of the strangeness of insect metamorphosis in his story called "The Metamorphosis", as have several authors since.[1]

Ant

Anthropomorphised ants have often been used in fables, children's stories, and religious texts to represent industriousness and cooperative effort.[2] In the Book of Proverbs, ants are held up as a good example for humans for their hard work and cooperation. Aesop did the same in his fable "The Ant and the Grasshopper". In the Quran, Sulayman is said to have heard and understood an ant warning other ants to return home to avoid being accidentally crushed by Sulayman and his marching army.[3][4] Mark Twain wrote about ants in his 1880 book A Tramp Abroad.[5] Some modern authors have used ants to comment on the relationship between society and the individual, as with Robert Frost in his poem "Departmental" and T. H. White in his fantasy novel The Once and Future King. The plot in the French entomologist and writer Bernard Werber's Les Fourmis science-fiction trilogy is divided between the worlds of ants and humans; ants and their behaviour are described using contemporary scientific knowledge. H.G. Wells wrote about intelligent ants destroying human settlements in Brazil and threatening human civilization in his 1905 science-fiction short story, The Empire of the Ants. The myrmecologist E. O. Wilson wrote a short story, "Trailhead" in 2010 for The New Yorker magazine, describing the life and death of an ant-queen and the rise and fall of her colony, from an ants' point of view.[6]

Bee

Beatrix Potter's illustrated children's book The Tale of Mrs Tittlemouse (1910) features the bumblebee Babbity Bumble and her brood (pictured).

The poet W. B. Yeats wrote The Lake Isle of Innisfree (1888) with the honey bee couplet "Nine bean rows will I have there, a hive for the honey bee, / And live alone in the bee loud glade", while he was living in Bedford Park, London.[7]

Butterfly

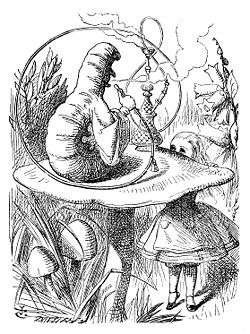

Sir John Tenniel drew a famous illustration of Alice meeting a caterpillar for Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland, c. 1865. The caterpillar is seated on a toadstool and is smoking a hookah pipe; the image can be read as showing either the forelegs of the larva, or as suggesting a face with protruding nose and chin.[8][9] Eric Carle's children's book The Very Hungry Caterpillar portrays the larva as an extraordinarily hungry animal, while also teaching children how to count (to five) and the days of the week.[8]

A. S. Byatt's 1992 novella Morpho Eugenia[lower-alpha 1] (published in Angels and Insects) tells of the shipwreck of a young naturalist, William, on his way back from studying insects in the Amazon.[lower-alpha 2] He is rescued by the Alabaster family, and marries their daughter Eugenia: but she turns out to have a different obsession from his Morpho butterflies.[10]

Vladimir Nabokov was the son of a professional lepidopterist,[11] and became an expert on butterflies himself. He wrote his novel Lolita while travelling on his annual butterfly-collection trips in the western United States.[12]

Lafcadio Hearn's essay Butterflies analyses the treatment of the butterfly in Japanese literature, both prose and poetry. He notes that these often allude to Chinese tales, such as of the young woman that the butterflies took to be a flower. Among the brief 17-syllable Japanese Haiku poems about butterflies, of which he translates 22, one by the Haiku master Matsuo Bashō is said to suggest happiness in springtime: "Wake up! Wake up!—I will make thee my comrade, thou sleeping butterfly." Another compares the butterfly's shape to a Japanese silk upper-dress, the haori, "being taken off". A third says they look to be girls of "about seventeen or eighteen years old." Hearn retells, too, the old story of a man who dies after 50 years alone, having mourned his sweetheart Akiko daily all that time. As he dies, "a very large white butterfly entered the room, and perched upon the sick man's pillow." The man smiles in death. "Then it must have been Akiko!", says an old woman who knew him.[13]

Dragonfly

Lafcadio Hearn wrote in his 1901 book A Japanese Miscellany that Japanese poets had created dragonfly haiku "almost as numerous as are the dragonflies themselves in the early autumn."[14] The poet Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694) wrote haiku such as "Crimson pepper pod / add two pairs of wings, and look / darting dragonfly", relating the autumn season to the dragonfly.[15] Hori Bakusui (1718–1783) similarly wrote "Dyed he is with the / Colour of autumnal days, / O red dragonfly."[14]

The poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, described a dragonfly splitting its old skin and emerging shining metallic blue like "sapphire mail" in his 1842 poem "The Two Voices", with the lines "An inner impulse rent the veil / Of his old husk: from head to tail / Came out clear plates of sapphire mail."[16]

The novelist H. E. Bates described the rapid, agile flight of dragonflies in his 1937 nonfiction book[17] Down the River:[18]

I saw, once, an endless procession, just over an area of water-lilies, of small sapphire dragonflies, a continuous play of blue gauze over the snowy flowers above the sun-glassy water. It was all confined, in true dragonfly fashion, to one small space. It was a continuous turning and returning, an endless darting, poising, striking and hovering, so swift that it was often lost in sunlight.[19]

Fly

In the Biblical fourth plague of Egypt, flies represent death and decay. Myiagros was a god in Greek mythology who chased away flies during the sacrifices to Zeus and Athena; Zeus sent a fly to bite Pegasus, causing Bellerophon to fall back to Earth when he attempted to ride the winged steed to Mount Olympus. In the traditional Navajo religion, Big Fly is an important spirit being.[20][21][22]

The Impertinent Insect is a group of five fables, sometimes ascribed to Aesop, concerning an insect which may be a fly, gnat, or flea, and which puffs itself up to seem important.

In the 15th-century trompe l'oeil painting Portrait of a Carthusian (1446) by Petrus Christus, a fly sits on a fake frame.[23]

Emily Dickinson's 1855 poem "I Heard a Fly Buzz When I Died" also makes reference to flies in the context of death. In fact, flies such as the genus Hydrotaea are used in forensic cases to determine time of death for corpses. In William Golding's 1954 novel Lord of the Flies, the fly is a symbol of the children involved.

Grasshopper, locust

Although grasshoppers and locusts are closely related, locusts being the migratory forms of certain grasshoppers, they are treated very differently in literature. One of Aesop's Fables, already mentioned under "Ant", later retold by La Fontaine, is the tale of The Ant and the Grasshopper. The ant works hard all summer, while the grasshopper plays. In winter, the ant is ready but the grasshopper starves. Somerset Maugham's short story "The Ant and the Grasshopper" explores the fable's symbolism via complex framing.[24] The Canadian philosopher Bernard Suits retells the story with the grasshopper as "the exemplification of the life most worth living."[25] Other human weaknesses besides improvidence have become identified with the grasshopper's behaviour.[26] So an unfaithful woman (hopping from man to man) is "a grasshopper" in "Poprygunya", an 1892 short story by Anton Chekhov,[27] and in Jerry Paris's 1969 film The Grasshopper.[28][29]

Plagues of locusts, the migratory forms of certain grasshoppers, are mentioned in literature throughout history. The insects arrived unexpectedly, often after a change of wind direction or weather, and the consequences were devastating. The Ancient Egyptians carved locusts on tombs in the period 2470 to 2220 BC, and a devastating plague is mentioned in the Book of Exodus in the Bible, as taking place in Egypt around 1300 BC.[30][31] Plagues of locusts are also mentioned in the Quran.[32]

Horsefly

The Ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus has a gadfly pursue and torment Io, a maiden associated with the moon, watched constantly by the eyes of the herdsman Argus, associated with all the stars: "Io: Ah! Hah! Again the prick, the stab of gadfly-sting! O earth, earth, hide, the hollow shape—Argus—that evil thing—the hundred-eyed." William Shakespeare, inspired by Aeschylus, has Tom o'Bedlam in King Lear, "Whom the foul fiend hath led through fire and through flame, through ford and whirlpool, o'er bog and quagmire", driven mad by the constant pursuit.[33] In Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare likens Cleopatra's hasty departure from the Actium battlefield to that of a cow chased by a gadfly: "The breeze [gadfly] upon her, like a cow in June / hoists sail and flies", where "June" may allude not only to the month but also to the goddess Juno who torments Io; and the cow in turn may allude to Io, who is changed into a cow in Ovid's Metamorphoses.[34]

The physician and naturalist Thomas Muffet wrote that the horse-fly "carries before him a very hard, stiff, and well-compacted sting, with which he strikes through the Oxe his hide; he is in fashion like a great Fly, and forces the beasts for fear of him only to stand up to the belly in water, or else to betake themselves to wood sides, cool shades, and places where the wind blowes through."[35] The "Blue Tail Fly" in the eponymous song was probably the mourning horsefly (Tabanus atratus), a tabanid with a blue-black abdomen common to the southeastern United States.[36]

Wasp

The Ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes wrote the comedy play Σφῆκες (Sphēkes), The Wasps, first put on in 422 BC. The "wasps" are the chorus of old jurors.[37]

The fantasy and science fiction author H. G. Wells made use of giant wasps in his 1904 novel The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth:[38]

It flew, he is convinced, within a yard of him, struck the ground, rose again, came down again perhaps thirty yards away, and rolled over with its body wriggling and its sting stabbing out and back in its last agony. He emptied both barrels into it before he ventured to go near. When he came to measure the thing, he found it was twenty-seven and a half inches across its open wings, and its sting was three inches long. ... The day after, a cyclist riding, feet up, down the hill between Sevenoaks and Tonbridge, very narrowly missed running over a second of these giants that was crawling across the roadway.[38]

In 1917 the ghost story author Algernon Blackwood wrote An Egyptian Hornet, about a beast at once alarming and beautiful: "From a distance he examined this intrusion of the devil. It was calm and very still. It was wonderfully made, both before and behind. Its wings were folded upon its terrible body. Long, sinuous things, pointed like temptation, barbed as well, stuck out of it. There was poison, and yet grace, in its exquisite presentment." The story contrasts the reactions to the threat of the churchman, the Reverend James Milligan, and the "depraved" Mr. Mullins.[39]

The science fiction writer Eric Frank Russell's 1957 Wasp, generally considered his best novel, has its protagonist, James Mowry, as a "wasp" terrorist, a small but deadly Terran (human) force in the Sirian Empire's midst.[40]

See also

- Cockchafer (May bug)

Notes

- ↑ The title puns on the name of the Eugene Morpho, a neotropical butterfly from French Guiana.

- ↑ In this, William resembles the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who was shipwrecked on his way home from the Amazon, losing his entire collection when his ship caught fire.

References

- ↑ Hogue, Charles (1987). "Cultural Entomology". Annual Review of Entomology. Insects.org. 32. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ "Vol 4, Book 54, Number 536". Sahih Bukhari.

- ↑ [Quran 27:18]

- ↑ Deen, Mawil Y. Izzi (1990). "Islamic Environmental Ethics, Law, and Society". In Engel, J.R.; Engel, J.G. Ethics of Environment and Development (PDF). Bellhaven Press.

- ↑ Twain, Mark (1880). "22 The Black Forest and Its Treasures". A Tramp Abroad. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510137-5.

- ↑ Wilson, E.O. (25 January 2010). "Trailhead". The New Yorker. pp. 56–62.

- ↑ Deering, Chris. "Yeats in Bedford Park". ChiswickW4.com. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- 1 2 Marren, Peter; Mabey, Richard (2010). Bugs Britannica. Chatto and Windus. pp. 196–205. ISBN 978-0-7011-8180-2.

- ↑ Donald A. Ringe, A Linguistic History of English: From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (Oxford: Oxford, 2003), 232.

- ↑ Byatt, A. S. (1993) [1992]. Morpho Eugenia. Angels and Insects. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-099-22431-0.

- ↑ Nabokov, Vladimir (April 2000). "Father's Butterflies". The Atlantic online. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ Amis, Martin (1994) [1993]. Visiting Mrs Nabokov: And Other Excursions. Penguin Books. pp. 115–18. ISBN 0-14-023858-1.

- ↑ Hearn, 2015. Pages 1–18

- 1 2 Waldbauer, Gilbert; Waldbauer, Gilbert (30 June 2009). A Walk around the Pond: insects in and over the water. Harvard University Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-674-04477-7.

- ↑ Mitchell, Forrest Lee; Lasswell, James (2005). A Dazzle Of Dragonflies. Texas A&M University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-58544-459-5.

- ↑ Tennyson, Alfred, Lord (17 November 2013). Delphi Complete Works of Alfred, Lord Tennyson (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. pp. 544–545. ISBN 978-1-909496-24-8.

- ↑ "Down the River". H. E. Bates Companion. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ↑ Powell, Dan (1999). A Guide to the Dragonflies of Great Britain. Arlequin Press. p. 7. ISBN 1-900-15901-5.

- ↑ Bates, H. E. (12 February 1937). "Country Life: Pike and Dragonflies". The Spectator (5668): 269 (online p. 17).

- ↑ Leland Clifton Wyman (1983). "Navajo Ceremonial System". Handbook of North American Indians (PDF). Humboldt State University. p. 539.

Nearly every element in the universe may be thus personalized, and even the least of these such as tiny Chipmunk and those little insect helpers and mentors of deity and man in the myths, Big Fly (Dǫ’ soh) and Ripener (Corn Beetle) Girl (’Anilt’ ánii ’At’ ééd) (Wyman and Bailey 1964:29–30, 51, 137–144), are as necessary for the harmonious balance of the universe as is the great Sun.

- ↑ Leland Clifton Wyman & Flora L. Bailey (1964). Navaho Indian Ethnoentomology. Anthropology Series. University of New Mexico Press. LCCN 64024356.

- ↑ "Native American Fly Mythology". Native Languages of the Americas website.

- ↑ "Portrait of a Carthusian". Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2006.

- ↑ Sopher, H. (1994). "Somerset Maugham's "The Ant and the Grasshopper": The Literary Implications of Its Multilayered Structure". Studies in Short Fiction. 31 (1 (Winter 1994)): 109–. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ Suits, Bernard (2005) The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia. Broadview Press. ISBN 1770480110

- ↑ Klein, Barrett A. (2012). "The Curious Connection Between Insects and Dreams". Insects. 3: 1–17. doi:10.3390/insects3010001.

- ↑ Loehlin, James N. (2010). The Cambridge Introduction to Chekho v. Cambridge University Press. pp. 80–83. ISBN 978-1-139-49352-9.

- ↑ Greenspun, Roger (28 May 1970). "Movie Review: The Grasshopper (1969)". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Aeronca L-3B Grasshopper". The Museum of Flight.

- ↑ Krall, S.; Peveling, R.; Diallo,B.D. (1997). New Strategies in Locust Control. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 453–454. ISBN 978-3-7643-5442-8.

- ↑ Book of Exodus. pp. 10: 13–15.

And Moses stretched forth his rod over the land of Egypt, and the Lord brought an east wind upon the land all that day, and all that night; and when it was morning, the east wind brought the locusts. 14 And the locust went up over all the land of Egypt, and rested in all the coasts of Egypt: very grievous were they; before them there were no such locusts as they, neither after them shall be such. 15 For they covered the face of the whole earth, so that the land was darkened; and they did eat every herb of the land, and all the fruit of the trees which the hail had left: and there remained not any green thing in the trees, or in the herbs of the field, through all the land of Egypt.

- ↑ Showler, Allan T. (2008). "Desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria Forskål (Orthoptera: Acrididae) plagues". In John L. Capinera. Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer. pp. 1181–1186. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- ↑ Stagman, Myron (11 August 2010). Shakespeare's Greek Drama Secret. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 205–208. ISBN 978-1-4438-2466-8.

- ↑ Walker, John Lewis (2002). Shakespeare and the Classical Tradition: An Annotated Bibliography, 1961–1991. Taylor & Francis. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-8240-6697-0.

- ↑ Marren, Peter; Mabey, Richard (2010). Bugs Britannica. Chatto & Windus. pp. 310–312. ISBN 978-0-7011-8180-2.

- ↑ Eaton, Eric R.; Kaufman, Kenn (2007). "Deer flies and horse flies". Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Hillstar Editions. p. 284. ISBN 0-618-15310-1.

- ↑ "Ancient Greece – Aristophanes – The Wasps". Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- 1 2 Wells, H. G. (1904). Food of the Gods. Macmillan.

- ↑ Blackwood, Algernon. "An Egyptian Hornet". Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ Russell, Eric Frank (1957). Wasp. Gollancz Science Fiction. ISBN 0-575-07095-1.

Sources

- Hearn, Lafcadio (2015). Insect Literature (Limited (300 copies) ed.). Dublin: Swan River Press. ISBN 978-1-78380-009-4.

- Morris, Brian (2006) [2004]. Cultural Entomology. Insects and Human Life. Berg. pp. 181–216. ISBN 978-1-84520-949-0.