Molluscs in culture

Molluscs play a variety of roles in culture, including as food, as shell money, as dyestuffs, as musical instruments, for personal adornment with seashells, pearls, or mother-of-pearl, as items to be collected, as fictionalised sea monsters, and as raw materials for craft items such as Sailor's Valentines.

Practical uses

Adornment

Seashells are admired and collected by conchologists and others for scientific purposes and for their decorative qualities.[1]

Seashells have been used for personal adornment, such as the strings of cowries in the traditional dress of the Kikuyu people of Kenya,[2] and the formal dress of the Pearly Kings and Queens of London.[3]

Most molluscs with shells can produce pearls, but only the pearls of bivalves and some gastropods, whose shells are lined with nacre, are valuable.[4][5] The best natural pearls are produced by marine pearl oysters, Pinctada margaritifera and Pinctada mertensi, which live in the tropical and subtropical waters of the Pacific Ocean. Natural pearls form when a small foreign object gets stuck between the mantle and shell.

Pearls for use as jewellery are cultured by inserting either "seeds" or beads into oysters. The "seed" method uses grains of ground shell from freshwater mussels, and overharvesting for this purpose has endangered several freshwater mussel species in the southeastern United States.[5] The pearl industry is so important in some areas, significant sums of money are spent on monitoring the health of farmed molluscs.[6]

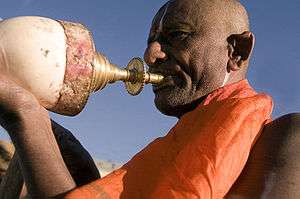

Musical instruments

Seashells including the sacred chank or shankha Turbinella pyrum; "Triton's trumpet" Charonia tritonis; and the Queen Conch Strombus gigas have been used as musical instruments around the world.[7][8][9]

For craft items

Seashells have been made into craft items such as Sailor's Valentines in the 19th century. Souvenir items, now considered as serious art, are made by Aboriginal women from La Perouse in Sydney.[10]

As food

Many species of molluscs, including gastropods such as whelks, bivalves such as scallops, cockles, mussels, and clams, and cephalopods such as octopuses and squids are collected or hunted for food.[11][12] Oysters[13] abalone,[14][15] and several species of mussels are widely farmed; oyster farming began in Roman times.[16][17][18][19]

Terrestrial snails are items of diet in French cuisine.[20]

Imperial purple

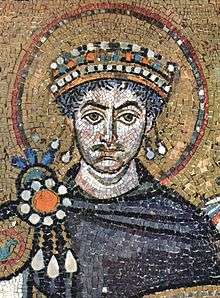

Tyrian or imperial purple, made from the ink glands of murex shells, "... fetched its weight in silver" in the fourth century BC, according to Theopompus.[21] The discovery of large numbers of Murex shells on Crete suggests the Minoans may have pioneered the extraction of "imperial purple" during the Middle Minoan period in the 20th–18th centuries BC, centuries before the Tyrians.[22][23]

Sea silk

Sea silk is a fine, rare, and valuable fabric produced from the long silky threads (byssus) secreted by several bivalve molluscs, particularly Pinna nobilis, to attach themselves to the sea bed.[24] Procopius, writing on the Persian wars circa 550 CE, "stated that the five hereditary satraps (governors) of Armenia who received their insignia from the Roman Emperor were given chlamys (or cloaks) made from lana pinna. Apparently, only the ruling classes were allowed to wear these chlamys."[25]

Shell money

Peoples of the Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean, North America, Africa and the Caribbean have used shells as money, including Monetaria moneta, the money cowrie[26] in preindustrial societies. However, these were not necessarily used for commercial transactions, but mainly as social status displays at important occasions, such as weddings.[27] When used for commercial transactions, they functioned as commodity money, as a tradable commodity whose value differed from place to place, often as a result of difficulties in transport, and which was vulnerable to incurable inflation if more efficient transport or "goldrush" behaviour appeared.[28]

Symbolic uses

Snails

The snail features in an animal epithet for its stereotypical slowness.[29]

Monsters of the deep

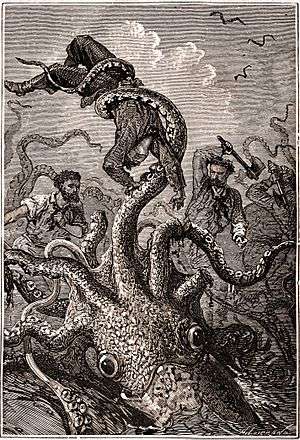

Cephalopod molluscs including the octopus and giant squid have featured as monsters of the deep since classical times. Giant squid are described by Aristotle (4th century BC) in his History of Animals[30] and Pliny the Elder (1st century AD) in his Natural History.[31][32][33] The Gorgon of Greek mythology may have been inspired by the octopus or squid, the octopus itself representing the severed head of Medusa, the beak as the protruding tongue and fangs, and its tentacles as the snakes.[34] The six-headed sea monster of the Odyssey, Scylla, may have had a similar origin. The Nordic legend of the kraken may also have derived from sightings of large cephalopods; the science fiction writer Jules Verne told a tale of a kraken-like monster in his 1870 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.[35]

The Venus shell

In his 1758 Systema Naturae, and then in his 1771 Fundamenta Testaceologiae, the pioneering taxonomist Carl Linnaeus used a series of "disquieting[ly]"[36] sexual terms to describe the Venus shell: vulva, anus, nates (buttocks), pubis, mons veneris, labia, hymen.[36][37][38] Further, he named the species Venus dione, for Venus, the goddess of love, and Dione, her mother. The evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould called Linnaeus's description "one of the most remarkable paragraphs in the history of systematics".[36][39] Some later naturalists found the terms used by Linnaeus uncomfortable; an 1803 review commented that "a few of these terms however strongly they may be warranted by the similitudes and analogies which they express, ... are not altogether reconcilable with the delicacy proper to be observed in ordinary discourse",[36] while the 1824 Supplement to the Encyclopaedia Britannica criticised Linnaeus for "indulg[ing] in obscene allusions."[36]

See also

- Category:Molluscs in popular culture

References

- ↑ "Home page". The Conchological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ White, Stewart Edward (2015). African Camp Fires. Read Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4733-7064-7.

- ↑ Swinnerton, Jo (2004). The London Companion. Robson. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-861-05799-0.

- ↑ Ruppert, pp. 300–343

- 1 2 Ruppert, pp. 367–403

- ↑ Jones, J.B.; Creeper, J. (April 2006). "Diseases of Pearl Oysters and Other Molluscs: a Western Australian Perspective". Journal of Shellfish Research. 25 (1): 233–238. doi:10.2983/0730-8000(2006)25[233:DOPOAO]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Novella, R. "SHELL TRUMPETS FROM WESTERN MEXICO". Institute of Archaeology, University College London: 42–51.

- ↑ "Conch Shell Trumpet (Davui)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ Montagu, Jeremy (2007). Origins and Development of Musical Instruments. Scarecrow Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8108-7770-2.

- ↑ "Shellwork Sydney Harbour Bridge". National Museum of Australia Collections. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ Garrow, J.S., Ralph, A., and James, W.P.T. (2000). Human Nutrition and Dietetics. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 370. ISBN 0-443-05627-7.

- ↑ "China catches almost 11m tonnes of molluscs in 2005". FAO. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ James Arnold Higginbotham, Piscinae: artificial fishponds in Roman Italy (University of North Carolina Press, 1997), p. 247, note 44 online; Cynthia J. Bannon, "Servitudes for Water Use in the Roman Suburbium," Historia 50 (2001), pp. 47–50. For more on these early efforts, see Sergius Orata.

- ↑ Taggart, Stewart (25 January 2002). "Abalone Farming on a Boat". Wired. Archived from the original on 16 August 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ Westaway, Cameron; Norriss, Jeff (October 1997). "Abalone Aquaculture in Western Australia" (PDF). Fisheries Management Paper. Fisheries Western Australia. ISSN 0819-4327.

- ↑ "Mussel Culture in British Columbia". BC Shellfish Growers Association.

- ↑ Calta, Marialisa (28 August 2005). "Mussels on Prince Edward Island". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ↑ Northern Economics. "The Economic Impact of Shellfish Aquaculture in Washington, Oregon and California" (PDF). Pacific Shellfish Institute. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ Kurlansky, Mark (2006). The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell. Ballantine Books. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-345-47638-8.

- ↑ "Snails as Food". Snail World. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ The fourth-century BC historian Theopompus, cited by Athenaeus (12:526) around 200 BC, according to Gulick, C.B. (1941). Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-99380-2.

- ↑ Reese, D.S. (1987). "Palaikastro Shells and Bronze Age Purple-Dye Production in the Mediterranean Basin". Annual of the British School of Archaeology at Athens. 82: 201–6. doi:10.1017/s0068245400020438.

- ↑ Stieglitz, R.R. (1994). "The Minoan Origin of Tyrian Purple". Biblical Archaeologist. 57 (1): 46–54. doi:10.2307/3210395. JSTOR 3210395.

- ↑ Webster's Third New International Dictionary (Unabridged) 1976. G. & C. Merriam Co., p. 307.

- ↑ Turner, R.D.; Rosewater, J. (June 1958). "The Family Pinnidae in the Western Atlantic". Johnsonia. 3 (38): 294.

- ↑ van Damme, Ingrid. "Cowry Shells, a trade currency". Museum of the National Bank of Belgium. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ Maurer, B. (October 2006). "The Anthropology of Money" (PDF). Annual Review of Anthropology. 35: 15–36. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123127. Archived from the original on August 16, 2007.

- ↑ Hogendorn, J.; Johnson, M. (2003). The Shell Money of the Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521541107. Particularly chapters "Boom and slump for the cowrie trade" (pages 64–79) and "The cowrie as money: transport costs, values and inflation" (pages 125–147)

- ↑ Pamatier, Robert Allen (1995). Speaking of Animals: A Dictionary of Animal Metaphors. Greenwood. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-313-29490-7.

- ↑ Aristotle. N.d. Historia animalium.

- ↑ Ellis, R. 1998. The Search for the Giant Squid. Lyons Press (London).

- ↑ Pliny the Elder. n.d. Naturalis historia.

- ↑ The Search for the Giant Squid: Chapter One. The New York Times.

- ↑ Wilk, Stephen R. (2000). Medusa:Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019988773X.

- ↑ Hogenboom, Melissa (12 December 2014). "Are massive squid really the sea monsters of legend?". BBC. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Da Costa and the Venus dione: The Obscenity of Shell Description". Retrieved 19 May 2015. From the Encyclopædia Romana by James Grout.

- ↑ Linnaeus (1758). Systema Naturae (10th ed.). pp. 684–685.

- ↑ Linnaeus (1767). Systema Naturae (12th ed.). pp. 1128–1129.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay (1995). "The Anatomy Lesson: The Teachings of Naturalist Mendes da Costa, a Sephardic Jew in King George's Court". Natural History. 104 (12): 10–15, 62–63.

Sources

Ruppert, E.E., Fox, R.S., and Barnes, R.D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7 ed.). Brooks / Cole. ISBN 0-03-025982-7.