Battersea

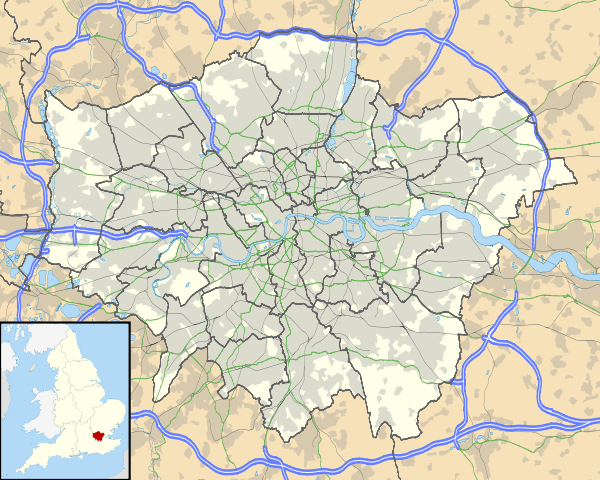

Coordinates: 51°27′50″N 0°10′04″W / 51.46377°N 0.16771°W

Battersea is a largely residential inner-city district of south London in the London Borough of Wandsworth, England. It has Battersea Park, one of southwest London's main parks, and is on the south side of the River Thames, 2.9 miles (4.8 km) south-west of Charing Cross.

Noted for the long-awaited bringing of the London Underground in the 21st century, two main railway lines cross here at what was the country's busiest station. In all directions along these lines are several of the borough's council estates which replaced some of the severely overcrowded housing serving its former Power Station, its locomotive, carriage and heavy industrial works, with interpretations and variants ranging from brutalist to spacious garden courtyards. Elsewhere in Battersea are a growing proportion of private architecturally-acclaimed riverside, parkside and typical London homes. In 2001, Battersea had a population of 75,651 people. Landmarks include New Covent Garden Market and the Royal Academy of Dance. Wandsworth Common and Clapham Common border parts of this large district, which traditionally also includes Nine Elms. Railway stations in Battersea are in fare zone 2.

History

Historically a part of Surrey, Battersea was centred on a church established on an island at the mouth of the Falconbrook; a small river that rises in Tooting Bec Common and flowed underground through south London to the River Thames.[1]

Battersea is mentioned in Anglo-Saxon times as Badrices īeg = "Badric's Island" and later "Patrisey". As with many former parishes beside major rivers some land was reclaimed by draining marshland and building culverts for streams.

The original village nucleus is marked by St. Mary's Church, which is on a site that has featured churches since the 9th Century. (The present church, which was completed in 1777, hosted the marriage of William Blake and Catherine Blake née Boucher in 1782; Benedict Arnold, his wife, Peggy Shippen and their daughter were buried in its crypt.)

The settlement appears in the Domesday Book as Patricesy, held by St Peter's Abbey, Westminster. Its Domesday Assets were: 18 hides and 17 ploughlands of cultivated land; 7 mills worth £42 9s 8d per year, 82 acres (33 ha) of meadow, woodland worth 50 hogs. It rendered (in total): £75 9s 8d.[2]

The former parish of Battersea included, in a detached part, a few hundred acres at Penge (and/or Crystal Palace).

The borough dates from the London Government Act of 1899, and includes the greater part of the original ecclesiastical parish of St. Mary Battersea. Under the same Act Penge, formerly a hamlet of Battersea, was constituted a separate urban district...the curious anomalies of [Battersea's] local government led to its formation as a separate urban district and its transfer to the county of Kent in 1900. Penge was a wooded district, over which the tenants of Battersea Manor had common of pasture.[3]

Agriculture

Before the Industrial Revolution, much of the large parish was farmland, providing food for the City of London and surrounding population centres; and with particular specialisms, such as growing lavender on Lavender Hill (nowadays denoted by the road of the same name), asparagus (sold as "Battersea Bundles") or pig breeding on Pig Hill (later the site of the Shaftesbury Park Estate). At the end of the 18th century, above 300 acres (1.2 km2) of land in the parish of Battersea were occupied by some 20 market gardeners, who rented from five to near 60 acres (240,000 m2) each.[4] Villages in the wider area: Wandsworth, Earlsfield (hamlet of Garratt), Tooting, Balham - were separated by fields; in common with other suburbs the wealthy of London and the traditional manor successors built their homes in Battersea and neighbouring areas.[5]

Industry

Industry in the area was concentrated to the north west just outside the Battersea-Wandsworth boundary, at the confluence of the River Thames, and the River Wandle which gave rise to the village of Wandsworth. This was settled from the 16th century by Protestant craftsmen - Huguenots - fleeing religious persecution in Europe, who planted lavender and gardens and established a range of industries such as mills, breweries and dyeing, bleaching and calico printing.[5] Industry developed eastwards along the bank of the Thames during the industrial revolution from 1750s onwards; the Thames provided water for transport, for steam engines and for water-intensive industrial processes. Bridges erected across the Thames encouraged growth; Putney Bridge, a mile to the west, was built in 1729, and Battersea Bridge in the centre of the north boundary in 1771. Inland from the river, the rural agricultural community persisted.[5]

Along the Thames, a number of large and, in their field, pre-eminent firms grew; notably the Morgan Crucible Company, which survives to this day and is listed on the London Stock Exchange; Price's Candles, which also made cycle lamp oil; and Orlando Jones' Starch Factory. The 1874 Ordnance Survey map of the area shows the following factories, in order, from the site of the as yet unbuilt Wandsworth Bridge to Battersea Park: Starch manufacturer; Silk manufacturer; (St. John's College); (St. Mary's Church); Malt house; Corn mill; Oil and grease works (Prices Candles); Chemical works; Plumbago Crucible works (later the Morgan Crucible Company); Chemical works; Saltpetre works; Foundry. Between these were numerous wharfs for shipping.

In 1929, construction started on Battersea Power Station, being completed in 1939. From the late 18th century to comparatively recent times Battersea, and certainly north Battersea, was established as an industrial area with all of the issues associated with pollution and poor housing affecting it.

Industry declined and moved away from the area in the 1970s, and local government sought to address chronic post-war housing problems with large scale clearances and the establishment of planned housing. Some decades after the end of large scale local industry, resurgent demand among magnates and high income earners for parkside and riverside property close to planned Underground links has led to significant construction. Factories have been demolished and replaced with modern apartment buildings. Some of the council owned properties have been sold off and several traditional working men's pubs have become more fashionable bistros. Battersea neighbourhoods close to the railway have some of the most deprived local authority housing in the Borough of Wandsworth. An area which saw condemned slums after their erection in the Victoria era.[6]

Railway age

Battersea was radically altered by the coming of railways. The London and Southampton Railway Company engineered their railway line from east to west through Battersea, in 1838, terminating at the original Nine Elms railway station at the north west tip of the area. Over the next 22 years five other lines were built, across which all trains from London's Waterloo and Victoria termini would as today travel. An interchange station was built in 1863 towards the north west of the area, at a junction of the railway. Taking the name of a fashionable village a mile and more away, the station was named 'Clapham Junction': a campaign to rename it "Battersea Junction" fizzled out as late as the early twentieth century. During the latter decades of the nineteenth century Battersea had developed into a major town railway centre with two locomotive works at Nine Elms and Longhedge and three important motive power depots (Nine Elms, Stewarts Lane and Battersea) all situated within a relatively small area in the north of the district. The effect was precipitate: a population of 6,000 people in 1840 was increased to 168,000 by 1910; and save for the green spaces of Battersea Park, Clapham Common, Wandsworth Common and some smaller isolated pockets, all other farmland was built over, with, from north to south, industrial buildings and vast railway sheds and sidings (much of which remain), slum housing for workers, especially north of the main east–west railway, and gradually more genteel residential terraced housing further south.

The railway station encouraged the government to site its buildings in the area surrounding Clapham Junction, where a cluster of new civic buildings including the town hall, library, police station, court and post office was developed along Lavender Hill in the 1880s and 1890s. The Arding and Hobbs department store, diagonally opposite the station, was the largest of its type at the time of its construction in 1885; and the streets near the station developed as a regional shopping district. The area was served by a vast music hall - The Grand - opposite the station (nowadays serving as a nightclub and venue for smaller bands) as well as a large theatre next to the Town Hall (the Shakespeare Theatre, later redeveloped following bomb damage). All this building around the station shifted the focus of the area southwards, and marginalised Battersea High Street (the main street of the original village) into no more than an extension of Falcon Road.

Housing estates

Battersea has a large area of mid-20th century public housing estates, almost all located north of the main railway lines and spanning from Fairfield in the west to Queenstown in the east.[7]

There are four particularly large estates. The Winstanley Estate, perhaps being the most renowned of them all, is known as being the birthplace to the garage collective So Solid Crew.[8] Winstanley is close to Clapham Junction railway station in the northern perimeter of Battersea, and is currently being considered for comprehensive redevelopment as one of the London Mayor's new Housing Zones.[9] Further north towards Chelsea is the Surrey Lane Estate, and on Battersea Park Road is the Doddington and Rollo Estate. East, toward Vauxhall, is the Patmore Estate which is in close proximity to the Battersea Power Station.

Other smaller estates include York Road, Somerset, Savona, Badric Court, the Peabody Estate, Wynter Street Estate, Ethelburga Estate, Kambala Estate and Carey Gardens.

Governance

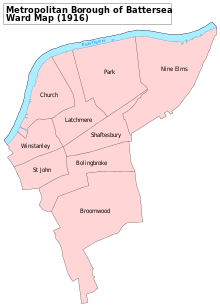

The tradition of local government in England was based on the Parish. Population growth in London during the 19th century demanded new arrangements, and the Metropolitan Borough of Battersea was created in 1899, with the boundaries described above. It was in 1965 combined with the neighbouring Metropolitan Borough of Wandsworth to form the London Borough of Wandsworth. The former Battersea Town Hall, opened in 1893, is now the Battersea Arts Centre.

In the period from 1880 onwards, Battersea was known as a centre of radical politics in the United Kingdom. John Burns founded a branch of the Social Democratic Federation, Britain's first organised socialist political party, in the borough and after the turmoil of dock strikes affecting the populace of north Battersea, was elected to represent the borough in the newly formed London County Council. In 1892, he expanded his role, being elected to Parliament for Battersea North as one of the first Independent Labour Party member of Parliament.

Battersea's radical reputation gave rise to the Brown Dog affair, when in 1904 the National Anti-Vivisection Society sought permission to erect a drinking fountain celebrating the life of a dog killed by vivisection. The fountain, forming a plinth for the statue of a brown dog, was installed near in the Latchmere Recreational Grounds, became a cause célèbre, fought over in riots and battles between medical students and the local populace until its removal in 1910.

The borough elected the first black mayor[10] in 1913 when John Archer took office, and in 1922 elected the Bombay-born Communist Party member Shapurji Saklatvala as MP for Battersea; one of only two communist members of Parliament.[10]

Battersea is currently divided into five Wandsworth wards. The Member of Parliament for the Battersea constituency since 6 May 2010 has been the Conservative Jane Ellison.

In 2009, it was announced that a new US embassy would be constructed at Nine Elms. This development would also see the building of luxury apartments in the area.

Geography

Battersea is part of London on the south bank of the River Thames. A cross between a square and a triangle in shape,[3] its northern boundary is the Thames, as it runs first north-east, and then east, before turning north again to pass Westminster. Its north-eastern corner is one mile (1.6 km) due south of the Palace of Westminster; the north-western corner is demarcated by Wandsworth Bridge and Battersea tapers south to a point roughly three miles (5 km) from the north-eastern corner and two miles (3 km) from the north-west. To the east is Lambeth and Stockwell; on the south are Camberwell and Streatham, on the south-east is Clapham and on the west Wandsworth.

Nearby places

|

Fulham | Chelsea | Pimlico |  |

| Wandsworth | |

Nine Elms and Stockwell | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Wandsworth and Balham | Balham and Clapham | Clapham |

Crime

Some parts of Battersea have become known for drug-dealing. The Winstanley and York Road council estates have developed a reputation for such offences and were included in a zero-tolerance "drug exclusion zone" in 2007.[11]

Demography

In 2011, Battersea had a population of 73,345.[12] The district was also 52.2% of White British origin,[13] as against an average for Wandsworth of 53.3%.

Landmarks

Within the bounds of modern Battersea are (from east to west):

- New Covent Garden Market, a major fruit and vegetable wholesale market, resited from Covent Garden in 1974. (Also considered by many to be in Nine Elms).

- Battersea Power Station an iconic edifice designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, built between 1929 and 1939 (featured, with flying pig, on the sleeve art of Pink Floyd's album Animals). There have been a number of failed regeneration projects since the late 1980s. The current proposals are to convert the disused shell into a mass entertainments and commercial complex, with dedicated transport links (a proposed extension of the Northern line from Kennington could be complete by 2020[14]).

- Battersea Dogs and Cats Home, formerly Battersea Dogs Home and prior to that the Temporary Home for Lost and Starving Dogs, established in Holloway in 1860 and moved to Battersea in 1871. It is the United Kingdom's most famous refuge for stray dogs. Also the main location for ITV 1's Paul O'Grady: For the Love of Dogs[10]

- Battersea Park, an 83 hectare green space laid out by Sir James Pennethorne between 1846 and 1864 and opened in 1858, and home to a zoo and the London Peace Pagoda.

- Shaftesbury Park Estate, conservation area consisting of over a thousand Victorian houses preserved in their original style.

- Battersea Arts Centre, in the former Battersea Town Hall

- Northcote Road, a bustling and famous local shopping street with its own market at the centre of the so-called Nappy Valley.

- Clapham Junction railway station, by at least one measure — passenger interchanges[15]— the busiest station in the United Kingdom and named after the neighbouring town of Clapham although it lies in the geographic heart of Battersea, SW11.

- Arding & Hobbs building, completed in 1912, now occupied by Debenhams.

- Large 24-hour Asda supermarket, adjacent to Clapham Junction station.

- St Mary's Church, Battersea. Benedict Arnold is buried here. Four stained glass windows celebrate Arnold, William Blake, William Curtis and J. M. W. Turner.

- Sir Walter St John's School, now Thomas's day school, was founded in 1700. Parts of the present building date back to 1859.

- Royal Academy of Dance, containing several studios and associated with the University of Surrey.

- The London Heliport, London's busiest heliport, sited on the Thames a half mile north of Clapham Junction station.

- Price's Candles on York Road, was the largest manufacturers of candles in the UK; now it has been converted into residential flats.

- Newton Preparatory School, in an Edwardian building (with modern extension) formerly occupied by Clapham College, Notre Dame School and Raywood Street School.

Transport

.jpg)

Railway stations

- Clapham Junction, Europe's busiest railway station.

- Battersea Park

- Queenstown Road

Proposed stations on the London Underground

- Battersea tube station (a station on the Northern line extension to Battersea)

- Clapham Junction (suggested Northern Line further extended from Battersea)

Former railway stations

- Battersea (closed 1940)

- Battersea Park Road (closed 1916)

In popular culture

Battersea features in the books of Michael de Larrabeiti, who was brought up in the area: A Rose Beyond the Thames recounts the working-class Battersea of the 1940s and 1950s; The Borrible Trilogy presents a fictional Battersea, home to fantasy creatures known as the Borribles. Battersea is also the setting for Penelope Fitzgerald's 1979 Booker Prize-winning novel, Offshore. Kitty Neale's Nobody's Girl is set ina fictional café and the surrounding Battersea High Street Market. Nell Dunn's 1963 novel Up the Junction (later adapted for both television and cinema) depicts contemporary life in the industrial slums of Battersea near Clapham Junction.

Michael Flanders, half of the 1960s comedy duo Flanders and Swann, often made fun of Donald Swann for living in Battersea. Morrissey mentions Battersea in his song "You're the One for Me, Fatty". Babyshambles recorded the song "Bollywood to Battersea" for a 2005 charity album Help!: A Day in the Life.

Prominent people

The following people have lived, or currently live, in Battersea:

- Ben Adams – musician from the group a1

- James Aldridge – writer

- Monie Love – mc and radio personality

- L. S. Bevington – anarchist poet and essayist, was born and grew up in a Quaker family on St Johns Hill.

- Ronnie Biggs – thief who took part in the Great Train Robbery

- Johnny Briggs – actor, best known as Mike Baldwin in Coronation Street

- Kathleen Byron – actress

- Emma Chambers – actress, known for her role as 'Alice' in "The Vicar of Dibley"

- Adrian Chiles – television presenter

- Brian Cox – physicist, host of science shows for BBC

- Colin Douglas – stage and television actor

- Nell Dunn – playwright

- Howard Eastman – boxer

- Craig Eastmond – footballer

- Freddie Foreman – criminal and associate of the Kray Twins, born in Sheepcote Lane

- Bob Geldof – singer and songwriter

- Pixie Geldof – socialite and model

- Graham Greene – writer, playwright, critic

- Rich Hall – comedian

- Harry Hill – comedian

- G. K. Chesterton – writer

- Simon Le Bon – musician

- Katie Leung – actress, best known as Cho Chang in Harry Potter films

- Kate Maberly – actress

- Terry Manning – music producer

- Noel McKoy – singer and songwriter

- Buster Merryfield – actor, best known as Uncle Albert in Only Fools and Horses

- Dannii Minogue – musician

- Seán O'Casey – writer

- John O'Farrell – writer[16]

- William Henry Page – historian and general editor of the Victoria County History

- Rick Parfitt – singer with Status Quo

- Polly Paulusma – musician

- Mervyn Peake – author[17]

- Rupert Penry-Jones – actor

- Debbie "MC Remedee" Pryce and Susan "Susie Q" Banfield of Cookie Crew – rappers

- Gordon Ramsay – chef

- Joely Richardson – actress

- J.K. Rowling – author[18]

- Greg Rusedski – tennis player

- John Scott – sociologist and Fellow of the British Academy

- Peter Serafinowicz – comedian

- George Shearing – Jazz pianist

- Ed Sheeran – musician

- Timothy Spall – actor[19]

- Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke

- Donald Swann – musician – of Flanders and Swann

- Gabriel Thomson – stars in My Family

- Baroness Trumpington – member of the House of Lords

- Vivienne Westwood – fashion designer

- William Wilberforce – prominent campaigner against the slave trade

- Edward Adrian Wilson – English physician, polar explorer, natural historian, painter and ornithologist

- Bob Marley – reggae artist

See also

References

- ↑ London Under London: A subterranean guide: Richard Trench and Ellis Hillman: ISBN 0-7195-5288-5

- ↑ Domesday Book for Surrey Archived 30 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Map Victoria County History, London, H.E. Malden (Ed), 1911

- ↑ 'Battersea', The Environs of London: volume 1: County of Surrey (1792), pp. 26-48.

- 1 2 3 [H.E. Malden (editor) (1912). "Parishes: Battersea with Penge". A History of the County of Surrey: Volume 4. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ↑ Booth's Poverty Map London School of Economics archive. Retrieved 4 November 2014

- ↑ Battersea Profile Archived 29 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine., from Wandsworth Primary Care Trust, citing Census 2001

- ↑ Mark Blunden (20 February 2014). "London housing estate where So Solid Crew formed set for demolition". London Evening Standard.

- ↑ Mayor names London's first Housing Zones - Clapham Junction to Battersea Riverside zone Archived 25 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 Chris Roberts, Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: The Reason Behind Rhyme, Thorndike Press,2006 (ISBN 0-7862-8517-6)

- ↑ 'Battersea', Special report: Class B for Battersea (2007), pp.1.

- ↑ "Battersea - Hidden London".

- ↑ Good Stuff IT Services. "Wandsworth". UK Census Data.

- ↑ "Northern line extension". tfl.gov.uk.

- ↑ Delta Rail, 2008-09 station usage report, Office of the Rail Regulation website

- ↑ ""Rebels don't make jokes about how excellent it is to have bishops in the House of Lords": An interview with John O'Farrell". The Croydon Citizen.

- ↑ "Literary Review – Fergus Fleming on Mervyn Peake". literaryreview.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013.

- ↑ Name of Asda store rekindles the ‘Clapham or Battersea’ row – News – London Evening Standard. Standard.co.uk (29 October 2010). Retrieved on 2013-08-24.

- ↑ "Timothy Spall: 'Turner had a god-given genius'". Telegraph.co.uk. 18 October 2014.

Further reading

- Patrick Loobey, Battersea Past. Historical Publications Ltd., 2002. ISBN 0-948667-76-1

- Peter Mason, The Brown Dog Affair. Two Sevens Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-9529854-0-3

- Martin Knight, Battersea Girl. Mainstream Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1-84596-150-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battersea. |