Battle of Pilckem Ridge

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

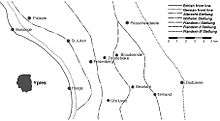

The Battle of Pilckem Ridge, 31 July – 2 August 1917, was the opening attack of the main part of the Third Battle of Ypres in the First World War. The British Fifth Army and Second Army and the French First Army on the northern flank, attacked the German 4th Army which defended the Western Front from Lille, to the Ypres Salient in Belgium and on to the North Sea coast. On 31 July the Anglo-French armies attacked the Ypres Salient and captured Pilckem (Flemish: Pilkem) Ridge and areas either side, the French attack being a great success. After several weeks of changeable weather, heavy rain began during the afternoon of 31 July. British observers in the XIX Corps area in the centre, lost sight of the troops that had advanced to the main objective at the green line and three reserve brigades pressing on towards the red line. The weather changed just as German regiments from specialist counter-attacking Eingreif divisions intervened. The three British reserve brigades were forced back through the green line to the intermediate black line, which the British artillery-observers could still see and the German counter-attack was stopped by massed artillery and small-arms fire.

The attack had mixed results; a substantial amount of ground was captured by the British and French, except on the Gheluvelt Plateau on the right flank, where only the blue line (first objective) and part of the black line (second objective) were captured. A large number of casualties were inflicted on the German defenders and 5,626 German prisoners were taken and the German Eingreif divisions managed to recapture some ground on the XIX Corps front, from the Ypres–Roulers railway, northwards to St. Julien. For the next few days both sides made local attacks to improve their positions, much hampered by the wet weather. The rains had a serious effect on operations in August, causing more problems for the British and French, who were advancing into the area devastated by artillery fire and partly flooded by the unseasonable rain. A local British attack on the Gheluvelt Plateau on 2 August, was postponed because of the weather until 10 August and the second big general attack due on 4 August, could not begin until 16 August. The 3rd Battle of Ypres became controversial while it was being fought and has remained so, with disputes about the predictability of the August deluges and for its mixed results, which in much of the writing in English, is blamed on misunderstandings between Gough and Haig and on faulty planning, rather than on the resilience of the German defence.

Background

Strategic background

Operations in Flanders, Belgium had been desired by the British Cabinet, Admiralty and War Office since 1914. Douglas Haig succeeded John French as Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force on 19 December 1915. A week after his appointment, Haig met Vice-Admiral Reginald Bacon, who emphasised the importance of obtaining control of the Belgian coast, to end the threat from German naval forces based in Bruges. In January 1916, Haig ordered General Henry Rawlinson to plan an attack in the Ypres Salient. The need to support the French army during the Battle of Verdun 21 February – 18 December 1916 and the demands of the Somme battles 1 July – 18 November 1916, absorbed the British Expeditionary Force's offensive capacity for the rest of the year.[1]

On 22 November Haig, Chief of the Imperial General Staff William Robertson, First Sea Lord Admiral Henry Jackson and Dover Patrol commander Vice-Admiral Reginald Bacon, wrote to General Joffre urging that the Flanders operation be undertaken in 1917, which Joffre accepted.[2] In late 1916 and early 1917, military leaders in Britain and France were optimistic that the casualties they had inflicted on the German army at the Battle of Verdun, the Battle of the Somme and on the Eastern Front had brought the German army close to exhaustion, although the effort had been immensely costly. At the conference in Chantilly in November 1916 and a series of subsequent meetings, the Entente agreed on an offensive strategy to overwhelm the Central Powers by means of simultaneous attacks on the Western, Eastern and Italian Fronts.[3]

The Prime Minister David Lloyd George, sought to limit British casualties and proposed an offensive on the Italian front. British and French artillery would be transferred to Italy to add weight to the offensive.[4] This suggestion was opposed by the French and Italian delegations and the British General Staff, at least covertly and was discarded.[5] The new French Commander-in-Chief, Robert Nivelle, believed that a concentrated attack by French forces on the Western Front during the spring of 1917, could break the German front and lead to a decisive victory. The Nivelle plan was welcomed by the British, despite many in the Cabinet and War Office being sceptical, because a French attack would mean a lesser burden falling on the British.[6] Haig was ordered to co-operate with Nivelle but secured French agreement that in the event the offensive failed, the British would attack in Flanders with French support.[7]

On 9 April, British and Empire forces undertook a preliminary attack at the Battle of Arras and the Nivelle Offensive began on 16 April. The French attack gained ground at great cost but no breakthrough leading to open warfare and the decisive defeat of the German army occurred, leading to Nivelle being replaced by Philippe Petain, a collapse in morale and mutinies in the French armies.[8] While the French recuperated, offensive action on the Western Front could only come from the BEF. It was not until June 1917 that the principle of a Flanders campaign was approved by the British Cabinet and more grudgingly by the Prime Minister, against his preference for an Italian campaign.[9]

British plans 1916–1917

Haig ordered General Herbert Plumer, the commander of the Second Army which occupied the Ypres Salient, to produce a plan in late 1916. Haig was dissatisfied with the limited scope of Plumer's plan for the capture of Messines Ridge and Pilkem Ridge – the name used in military circles for the higher ground around the small hamlet of Pilckem (Pilkem), within the dorp (village) of Boesinghe (Flemish: Boezinge). By early 1917, Haig felt that Nivelle's ambitious attempt at a decisive battle would either force the Germans to abandon the Belgian coast or that the German 4th Army in Flanders, would have divisions taken away to replace losses further south. Plumer produced a revised plan, in which in the first stage, Messines and Pilckem ridges would be captured, with an advance some distance onto the Gheluvelt Plateau; soon afterwards, an attack would be made across the Gheluvelt Plateau, to Passchendaele and beyond. Plumer believed that a force of 35 divisions and 5,000 guns would be necessary, which was far greater than the amount of artillery in the BEF.[10]

Haig also asked for an assessment from Colonel Macmullen on the General Headquarters staff, who proposed that the Gheluvelt Plateau be taken by a massed tank attack, reducing the need for artillery. In April, a reconnaissance by Captain Giffard LeQuesne Martel found that the area was unsuitable for tanks, because of narrow defiles between the three woods obstructing the approaches on the high ground and the broken state of the terrain. The tanks would have to detour north of Bellewaarde lake to Westhoek then wheel right at the German Albrecht Stellung.[11] From mid-1917, the area east of Ypres was defended by six German defensive positions: the front line, Albrecht Stellung (second line), Wilhelm Stellung (third line), Flandern I Stellung (fourth line), Flandern II Stellung (fifth line) and Flandern III Stellung (under construction). In between the German defence positions lay the Belgian villages of Zonnebeke and Passchendaele.[12] Plumer produced a second revision of his plan; Messines Ridge and the west end of the Gheluvelt Plateau would be attacked first and then Pilckem Ridge a short while later. The Fourth Army commander, General Henry Rawlinson proposed a plan to take Messines Ridge, then the Gheluvelt Plateau and Pilckem Ridge within 47–72 hours.[13]

On 14 February after discussions with Rawlinson, Plumer and Haig, Macmullen submitted a memorandum which became the GHQ 1917 plan. On 7 May, Haig set the timetable for the preliminary attack on Messines Ridge (7 June) and the Flanders offensive some weeks later. A week after the Battle of Messines Ridge, Haig informed his army commanders that his objectives were to wear down the German army, secure the Belgian coast and connect with the Dutch frontier. The armies were to capture Passchendaele Ridge and advance on Roulers and Thourout, to cut the railway supplying the German garrisons holding the Western Front north of Ypres and the Belgian coast. An attack by the Fourth Army would then begin on the coast, combined with Operation Hush (including an amphibious landing) in support of the main advance to the Netherlands frontier.[14] On 13 May, Haig appointed General Hubert Gough to command the Ypres operation and the coastal force; Macmullen gave Gough the GHQ 1917 plan the next day.[15]

Prelude

Entente offensive preparations

Gough held meetings with his Corps commanders on 6 and 16 June where the third objective of the GHQ 1917 plan, which included the German Wilhelm Stellung (third line), was added to the first and second objectives to be taken on the first day. A fourth objective was also given for the first day but was only to be attempted opportunistically, in places where the German defence had collapsed.[16] Gough intended to use five divisions from the Second Army, nine divisions and one brigade from the Fifth Army and two divisions from the French First Army (1re Armée).[17] Gough planned a preparatory bombardment from 16–25 July. The Second Army was to create the impression of a more ambitious attack beyond Messines Ridge, by capturing outposts in the Warneton line.[18] The Fifth Army was to attack along a front of approximately 14,000 yards (13,000 m), running from Klein Zillebeke in the south to the Ypres–Staden railway in the north, with the French First Army on the northern flank attacking with two divisions, from the boundary with the XIV Corps north to the flooded area just beyond Steenstraat. The infantry trained on a replica of the German trench system, built using information from aerial photographs and trench raids. Specialist platoons were given additional training on methods to destroy German pillboxes and blockhouses.[19]

The attack was not a breakthrough attempt, for the German fourth-line defensive position (the Flandern I Stellung), lay 10,000–12,000 yards (9,100–11,000 m) behind the front line, well beyond the fourth objective (red line).[20] Behind the Flandern I Stellung were the Flandern II Stellung and the Flandern III Stellung (still under construction).[21] In his Operation Order of 27 June to the Fifth Army corps commanders, Gough gave the green line (third objective) as the main objective. Advances towards the red line, (fourth objective) were to be made by patrols of fresh troops, to take vacant ground that was tactically valuable, exploiting any German disorganisation in the first 24 hours.[22][23] The Fifth Army plan was more ambitious than Plumer's version, which had involved a shallower advance of 1,000–1,750 yards (910–1,600 m) on the first day. Major-General John Davidson, Director of Operations at General Headquarters expressed concern that there was "ambiguity as to what was meant by a step-by-step attack with limited objectives".[24] Davidson suggested reverting to an advance of no more than 1,500–3,000 yards (1,400–2,700 m), to increase the concentration of British artillery.[25] Gough's reply stressed the need to plan for opportunities to take ground left temporarily undefended and that this was more likely in the first attack, that would have the benefit of a longer period of preparation.[26] After discussions at the end of June, Haig endorsed the Fifth Army plan, as did Plumer the Second Army commander.[27]

The front held by the French extended 4.3 miles (7 km) from Boesinghe (Boezinge) to the north of Nordschoote (Noordschote), the ground to the north being a morass created by the Belgians, when they flooded the area during the Battle of the Yser in 1914. A paved road between Reninghe, Nordschoote and Drie Grachten ran on a bank just above the water level. Into the inundations ran the Kemmelbeek, Yperlee (Yser Canal) and Martjevaart. Between Nordschoote and the Maison du Passeur pillbox, the opposing lines were separated by a wide stretch of ground, which was mostly flooded. At the Maison du Passeur there was a French outpost on the east side of the Yperlee, connected with the west bank by a footbridge. From this point to Steenstraat, no man's land was about 200–300 yards (180–270 m) wide. From Boesinghe to Steenstraat the Yperlee running from Ypres, formed the front line. The German trenches were on drier ground but barely above water level and parapets and breastworks had been built up, rather than trenches dug. It had proved impossible to build concrete artillery-observation posts, which left the position vulnerable to a surprise attack.[28]

The intended slow build-up of Allied air activity over the Ypres salient was changed to a maximum effort, after a weather delay on 11 July, due to the extent of the opposition of the Luftstreitkräfte.[29] The Germans had been sending larger formations into action and on 12 July, the greatest amount of air activity occurred since the beginning of the war. Thirty German fighters engaged Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and French fighters of the Service Aéronautique in a dogfight lasting an hour, the RFC losing nine aircraft and the Luftstreitkräfte fourteen. The Germans resisted the British and French air effort until the end of July, when their losses forced a change to more defensive tactics.[30] The attack was delayed on 1 July, at the request of Anthoine as the French needed more time to prepare artillery emplacements.[31] On 7 July, Gough asked for another postponement of five days. Some British heavy artillery had been lost to the German counter-bombardment, some had been delayed and bad weather had hampered the programme of counter-battery fire.[32] Haig agreed to delay until the 28 July. Anthoine then requested another delay because the poor weather had slowed his artillery preparation and after Gough supported Anthoine, Haig reluctantly agreed to delay to 31 July, even though this meant postponing Operation Hush from 7–8 August, to the next period of high tides.[33]

Plan of attack

The first of a series of set-piece attacks was to begin with an advance to three objectives, the blue, black and green lines, through the German front line system and then the Albrecht Stellung (second line) and Wilhelm Stellung (third line), which were approximately 1,000, 2,000 and 3,500 yards (910, 1,830 and 3,200 m) from the British front line, at any of which a halt could be called if necessary.[34][35] Local advances to the red line (fourth objective) 1,000–1,500 yards (910–1,370 m) further forward, by patrols from the reserve brigades into undefended ground, were left to the discretion of divisional commanders.[36] The Fifth Army had 752 heavy guns and 1,442 field guns, with support from 300 heavy guns and 240 field guns belonging to the French First Army in the north and 112 heavy guns and 210 field guns of the Second Army to the south. Gough also intended to use 120 tanks to support the attack, with another 48 held in reserve.[lower-alpha 1] Gough had five divisions of cavalry in reserve, a brigade of which was to be deployed if XIV Corps reached its objectives.[38]

The preliminary bombardment was intended to destroy German strong-points and trenches, cut barbed wire entanglements around German positions and to suppress German artillery with counter-battery fire. The first wave of infantry would advance under a creeping barrage moving at 100 yards (91 m) every four minutes, followed by more infantry advancing in columns or in artillery formation.[39] British intelligence expected the Germans to make the Albrecht Stellung their main line of resistance and to hold back counter-attacks until the British advance reached it, except on the Gheluvelt plateau where British intelligence expected the Germans to counter-attack quickly, given the importance of this commanding ground to both sides.[40][41] II Corps faced the Gheluvelt plateau and was given closer objectives than the other Fifth Army corps, 1,000 yards (910 m) forward at Klein Zillebeke in the south and 2,500 yards (2,300 m) at the junction with XIX Corps, on the Ypres–Roulers railway to the north.[42]

II Corps had five divisions at its disposal, compared to four each in the XIX, XVIII and XIV Corps. Three divisions and a brigade from one of the two divisions in reserve, would attack with support from approximately 43 percent of the Fifth Army artillery and the artillery of X Corps on the left flank of the Second Army.[lower-alpha 2] Footnotes and appendices in the History of the Great War, show that far from neglecting Haig's desire to concentrate on the Gheluvelt plateau, Gough put a disproportionate amount of the Fifth Army artillery at the disposal of II Corps for the 3 1⁄3 divisions engaged on 31 July, compared to four divisions with two engaged and two in reserve in the other corps, with an average of 19 percent of the Fifth Army artillery each. The green line for II Corps was the shallowest, from a depth of 1,000 yards (910 m) on the southern flank at Klein Zillibeke, to 2,500 yards (2,300 m) on the northern flank along the Ypres–Roulers railway.[44] The green line from the southern flank of XIX Corps to the northern flank of XIV Corps required an advance of 2,500–3,500 yards (2,300–3,200 m).[45]

The French First Army had the 29th Division and 133rd Division of the XXXVI Corps (Lieutenant-General Charles Nollet) and the 1st Division, 2nd Division, 51st Division and 162nd Division of I Corps (Lieutenant-General Paul Lacapelle). The I Corps had suffered many casualties in the Nivelle Offensive but had been recruited mainly from northern France and had been rested from 21 April until 20 June. The XXXVI Corps had garrisoned the North Sea coast since 1915 and had not been involved in the mutinies that took place on the Aisne front. The First Army was given 240 × 75 mm field guns, 277 trench artillery pieces (mostly 58 mm mortars), 176 heavy howitzers and mortars, 136 heavy guns and 64 super-heavy guns and howitzers, 22 being of 305 mm or more, 893 guns and mortars for 4.3 miles (7 km) of front.[46]

The 1re Armée had relieved the Belgian 4th Division and 5th Division from Boesinghe to Nordschoote from 5–10 July.[47] The 1re Armée was to advance with the 1st and 51st divisions of I Corps on the left of the Fifth Army as flank protection against a German counter-attack from the north.[48] The operation involved a substantial advance over difficult country, to capture the peninsula between the floods at the Martjevaart/St. Jansbeek stream and the land between there and the Yser Canal south of Noordshoote. The advance was to be by bounds to objective lines behind a creeping barrage moving at 90 m (98 yd) every four minutes, with pauses to make sure that the French barrage kept pace with the British barrage. The first objective was the two German lines east of the Yser Canal and the second objective was the German third line.[49]

A total advance of 5,000 yards (4,600 m) to the red line was not fundamental to the plan, being an attempt to provide enough discretion to the divisional commanders to make local advances without the need to request permission, based on the extent of local German resistance, in accordance with the manual SS 135. This was intended to avoid situations that had occurred in previous offensives, when vacant ground had not been promptly occupied and had then to be fought for in later attacks. Had the German defence collapsed and the red line been reached, the German Flandern I, II and III Stellungen would have been intact, except for Flandern I Stellung for a mile south of Broodseinde.[50] On 10 August, II Corps was required to reach the black line of 31 July, an advance of 400–900 yards (370–820 m) and at the Battle of Langemarck on 16 August, the Fifth Army was to advance 1,500 yards (1,400 m).[51]

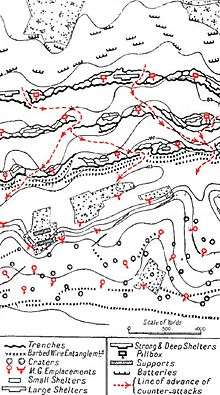

German defensive preparations

The German 4th Army operation order for the defensive battle was issued on 27 June.[52] The German 4th Army had about 600 aircraft of the Luftstreitkräfte, 200 being single-seat fighters; eventually eighty German air units operated over the Flanders front.[53][54] German defences had been arranged as a forward zone, main battle zone and rearward battle zone.[55] The defence in depth began with a front system of three breastworks each about 200 yards (180 m) apart, garrisoned by the four companies of each front battalion, with listening-posts in no man's land. About 2,000 yards (1,800 m) behind these works was the Albrecht Stellung (second line), a secondary or artillery protective line that marked the rear boundary of the forward zone. Companies of the support battalions were located at the back of the forward zone with half in the pillboxes of the Albrecht Stellung. Dispersed in front of the Albrecht Stellung were divisional sharpshooter machine-gun nests.[56]

The Albrecht Stellung marked the front of the main zone with the Wilhelm Stellung (third line), located a further 2,000 yards (1,800 m) away, marking the rear of the main zone. This zone contained most of the field artillery supporting the front divisions. In pillboxes of the Wilhelm Stellung were reserve battalions of the front-line regiments in divisional reserve. The rearward zone, located between the Wilhelm Stellung and the Flandern I Stellung, contained the support and reserve assembly areas for the Eingreif divisions. The German failures at the Battle of Verdun in December 1916 and at the Battle of Arras in April 1917 had given more importance to these areas, since the forward zones had been overrun and the garrisons lost. It was anticipated that the main defensive engagement would take place in the main battle zone, against attackers who had been slowed and depleted by the forward garrisons, reinforced if need be by the Eingreif divisions.[57]

The Germans planned a rigid defence of the front system and forward zone supported by counter-attacks. Local withdrawals according to the concept of elastic defence, was rejected by Lossberg the new 4th Army Chief of Staff, who believed that they would disorganise troops moving forward to counter-attack. Front line troops were not expected to cling to shelters, which were man traps but evacuate them as soon as the battle began and move forward and to the flanks to avoid British fire and to counter-attack. A small number of machine-gun nests and permanent garrisons were separate from the counter-attack organisation, to provide a framework for the re-establishment of defence in depth once an attack had been repulsed. German infantry equipment had recently been improved by the arrival of thirty-six MG08/15 machine-guns per regiment, which gave German units more means for fire and manoeuvre.[58]

Battle

Second Army

Due to the excellent observation possessed by the Germans, zero hour had been chosen for dawn at 3:50 a.m. but with mist and unbroken cloud at 500–800 feet (150–240 m), it was still dark when the British bombardment began. The shelling was maintained for six minutes, while the British infantry crossed the 200–300 yards (180–270 m) of no man's land, then the barrage began to creep forward at a rate of 100 yards (91 m) in four minutes. The attack extended from opposite Deûlémont in the Second Army area, to the boundary with the Fifth Army, to convince the Germans that a serious effort was being made to capture the Warneton–Zandvoorde line. The II Anzac Corps took the German outpost line west of the Lys river. The New Zealand Division captured La Basseville, south-west of Warneton, in street fighting with the German garrison, who eventually withdrew towards Warneton and the 3rd Australian Division captured outposts and strong points of the Warneton line near Gapaard.[59]

To the north, IX Corps with the 39th and 19th divisions, advanced 500 yards (460 m) astride the Wambeke and Roosebeke streams and down the Oosttaverne spur between them, to the blue line (first objective) 1,000–1,500 yards (910–1,370 m) forward. The 19th Division attacked from Bee Farm in the south to Forret in the north. Two battalions of the 37th Division were attached to the right flank of the 19th Division to capture the blue line, from July to Bee Farms and revert to the command of the 37th Division for the next phase, for an attack south of July Farm. The 19th Division attack was conducted by the 56th Brigade, with three attacking battalions and one in reserve. Each battalion assembled in the front line and the support battalions took post in the old British front line, which had been made redundant by the Battle of Messines in June, then advanced to occupy the vacated front-line positions, when the attack began. Artillery support came from the 19th divisional artillery, the left group of the 37th divisional artillery and two 6-inch batteries of the IX Corps heavy artillery; a machine-gun barrage was to be fired by about 30 machine-guns. The right battalion reached the objective very quickly, capturing Junction Buildings, Tiny and Spider farms, as the 63rd Brigade battalions of the 37th Division formed a defensive flank by 4:10 a.m. One of the 37th Division battalions had gained touch with the rest of their division on the right but a gap of 300 yards (270 m) had opened between Wasp Farm and Fly Buildings. Further to the left a 19th Division battalion had reached the blue line but further on the left, companies of the next attacking battalion has been pushed back south and south-west of Forret Farm. Prisoners claimed that the attack was expected later in the day and that a measure of surprise was obtained. Mopping up and consolidation began, although the unexpected darkness made this difficult.[60]

At about 5:30 a.m. German artillery fire increased and German soldiers were seen dribbling forward near Pillegrem's Farm, east of the junction with the 37th Division. Engineers and pioneers had begun work on strong points and communication trenches, despite the interference of the German barrage and by 11:00 a.m. had turned Tiny Farm into a strong point and completed communication trenches back to the old front line. More Germans were seen dribbling forward and small-arms fire became intense, when at 6:40 a.m. a smoke screen rose at the junction of the 19th and 37th divisions; the Germans attacked at 7:40 a.m. and overran some of the 63rd Brigade troops on the far right, only a small number getting back to Tiny Farm. Reinforcements from the 19th Division, were prevented from reaching the old front line by German machine-gun fire. More reinforcements arrived and defensive flanks were formed, until a counter-attack on Rifle Farm was organised at 8:00 p.m., which succeeded until a fresh German attack moments later forced it back again. A second attack in the north on Forret Farm was repulsed late in the day and the division was ordered to consolidate.[61]

X Corps attacked with the 41st Division on either side of the Comines canal, captured Hollebeke village and dug in 500–1,000 yards (460–910 m) east of Battle Wood. Much of the X Corps artillery was used to help the Fifth Army by counter-battery fire on the German artillery concentration behind Zandvoorde.[59] The 41st Division attack was hampered by frequent German artillery bombardments, in the days before the attack and the officers laying out markings for the assembly tapes during the night of 30 July, exchanged fire with a German patrol. High explosive and gas shelling never stopped and one battalion lost 100 casualties in the last few days before the attack. At zero hour the attack began and the division advanced down the hill to the first German outposts. At one part of the battlefield German pillboxes had been built in lines from the front-line to the rear, from which machine-gunners kept up a steady fire. The strong points on the left were quickly suppressed but those on the right held out for longer and caused many casualties, before German infantry sallied from shelters, between the front and support lines on the right, to be repulsed by British small arms fire and that of a Vickers machine-gun, fired by the Colonel in command of the battalion. Mopping-up the remaining pillboxes failed, due to the number of casualties and a shortage of ammunition. It began to rain and at 4:00 a.m. many Germans were seen massing for a counter-attack. Reinforcements were called for and rapid fire opened on the German infantry but the attack succeeded in reaching the pillboxes still holding out on the right. The British artillery began firing as reinforcements arrived, the Germans were forced back and the last pillboxes captured. The front line had been advanced about 600–650 yards (550–590 m) on a front of 2,500 yards (2,300 m), from south of Hollebeke north to the area east of Klein Zillebeke.[62]

Fifth Army

| Date | Rain mm |

Temp (°F) |

Outlook |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | 21.7 | 69 | overcast |

| 1 | 5.3 | 59 | — |

| 2 | 5.3 | 59 | — |

| 3 | 9.9 | 59 | — |

| 4 | 4.9 | 66 | overcast |

| 5 | 0.0 | 73 | clear |

| 6 | 0.1 | 71 | cloud |

| 7 | 0.0 | 69 | cloud |

| 8 | 10.2 | 71 | cloudy |

| 9 | 0.2 | 68 | clear |

| 10 | 1.5 | 69 | clear |

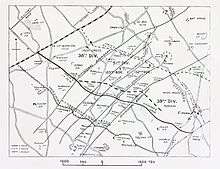

The attack began at 3:50 a.m., which was intended to coincide with dawn but low cloud meant that it was still dark.[64] The main British effort was made by II Corps across the Ghelveult Plateau, on the southern flank of the Fifth Army. II Corps had the most difficult task, advancing against the principal German defensive concentration of artillery, ground-holding and Eingreif divisions.[lower-alpha 3] The 17th Brigade on the right of 24th Division reached its objective 1,000 yards (910 m) east of Klein Zillebeke. The 73rd Brigade in the centre was stopped by German pillboxes at Lower Star Post and 72nd Brigade on the left reached the Bassevillebeek but then had to withdraw to a line south from Bodmin Copse, a few hundred yards short of the blue line (first objective).[65]

The 30th Division with an attached brigade of the 18th Division, had to advance across the Gheluvelt plateau to Glencorse Wood.[65] The 21st Brigade on the right lost the barrage as it crossed the wreckage of Sanctuary Wood and took until 6:00 a.m. to capture Stirling Castle Ridge. Attempts to advance further were stopped by German machine-gun fire. The 90th Brigade to the left was stopped on the first objective. German artillery fire fell on Sanctuary Wood and Chateau Wood from 5:00 a.m. and succeeded in stopping the advance, except for a short move forward of about 300 yards (270 m) south of Westhoek.[66] In the dark an 8th Division battalion had veered left into Château Wood and reported mistakenly that it had captured Glencorse Wood. The attached 53rd Brigade of 18th Division moved forward into ground that both divisions believed to be clear of German defenders. It was not until 9:00 a.m. that the mistake became known to the divisional commanders and the 53rd Brigade spent the rest of the day attacking an area that 30th Division had been intended to clear.[43] The 30th Division and 24th Division failed to advance far due to the boggy ground, loss of direction in the dark and because much of the German machine-gun defence on this section of the front remained intact.[67]

The 8th Division advanced towards Westhoek and took the Blue and Black lines relatively easily. The southern flank then became exposed to the concentrated fire of German machine-guns from Nonne Boschen and Glencorse Wood in the area to be taken by the 30th Division.[68] The difficulties of the 30th Division further south were unknown to the 8th Division until just before the 25th Brigade was due to advance over Westhoek Ridge. Brigadier-General Coffin decided that it was too late to stop the attack and sent a company of the reserve battalion to fill the gap to the south, which was not enough to stop German enfilade fire, so the Brigade consolidated on the reverse slope and held the crest with Lewis-gun posts. Pockets of ground lost to German counter-attacks were regained by British counter-attacks.[69] British artillery barrages made it impossible for German infantry advance further in this area.[70]

XIX Corps attacked with 15th Division on the right, next to the II Corps boundary along the Ypres–Roulers railway and 55th Division north to just short of St Julien. Their objective was the black line up the bare slope of Frezenberg Ridge, then across the valley of the Steenbeek to the green line on the far side. If German resistance collapsed, reserve brigades were to advance to the red line beyond Gravenstafel. The advance went well but then increasing resistance from fortified farms caused delays. Several tanks managed to follow the British infantry and attack strong-points like Bank Farm and Border House, allowing the advance to continue.[71] After a pause for consolidation on the black line, the reserve brigades of the XIX Corps divisions began their advance to the green line a mile beyond, as the sun came out and a mist formed. On the right the advance encountered enfilade fire, from the area not occupied by 8th Division beyond the Ypres–Roulers railway. The 164th Brigade of 55th Division had a hard fight through many German strong-points but took Hill 35 and crossed the Wilhelm (second) line, an eventual advance of about 4,000 yards (3,700 m).[72] Patrols pressed beyond the Zonnebeek–Langemarck road, one platoon taking fifty prisoners at Aviatik Farm on Gravenstafel spur.[73]

XVIII Corps reached the first objective and after an hour moved down to the Steenbeek, one of the muddiest parts of the battlefield, behind a smoke and shrapnel barrage. The 39th and 51st Divisions then established themselves on the stream for 3,000 yards (2,700 m), from St Julien to the Pilckem–Langemarck road. Several tanks were able to help capture strong-points delaying the advance and outposts were established across the stream.[74]

The attack had most success in the north, in the area of XIV Corps, with the Guards Division and 38th Division and I Corps of the French First Army. A lack of German activity east of the Yser canal, had led to the Guards Division crossing it without artillery preparation in the afternoon of 27 July. The German front line was found to be empty so the Guards lurked forward 500–700 yards (460–640 m) beyond the canal, as did the French 1st Division on the left. The 38th Division front line was on the east side and it moved forward slightly, against German small-arms and artillery-fire.[75] On this section of the front, the Entente forces advanced 3,000–3,500 yards (2,700–3,200 m) to the line of the Steenbeek river.[76] The preliminary bombardment had destroyed the front line of the German position and the creeping barrage supported the infantry attack at least as far as the first objective.[77] The infantry and some tanks dealt with German strong points, which were encountered after the first line and forward battle zone had been penetrated, pushing on towards the further objectives.[78] A number of field batteries moved forward once the black line had been captured, to join those established there before the attack, which had remained silent to avoid detection. Small cavalry probes were also carried out but German fire stopped them before they reached the green line.[79]

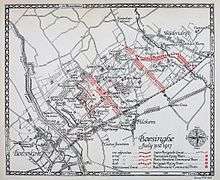

Première Armée

Two divisions of I Corps advanced at 3:50 a.m. on 31 July in a thick overcast, on a 3,000-yard (2,700 m) front, using 39 bridges thrown over the Yser canal since its occupation on 27 July. The German first line north to Steenstraat was taken easily and then the advance began on the second position.[80] The French kept pace with the Guards Division to the south, after a delay until 2:30 p.m. on the right at Colonel's Wood, caused by fire from German pillboxes, reached the final objectives then pressed on to take Bixschoote and Kortekeer Kabaret. In the early afternoon a German counter-attack at the junction of the Entente armies on the Steenbeek was repulsed. The position gained by the French was not easily defensible, consisting of craters half-full of water, which dissolved into rivulets when connected. Contact with the rear was difficult to maintain over the moonscape of shell-holes, many of them wide and of great depth but the French infantry had been issued supplies for four days to minimise the difficulty. The German 2nd Guard Reserve Division advanced through Houthoulst Forest towards the junction of the Fifth and French First armies but the attack bogged down in deep mud.[81] A prisoner said that in his company of about 150 men, barely fifty reached attacking distance and most of those took cover in shell-holes.[82] The first four days of August were exceptionally rainy, which added to the difficulty of maintaining troops in the ground captured on 31 July.[83] On 4 August despite the mud, the First Army advanced east of Kortekeer Kabaret and took two farms west of the road from Woumen to Steenstraat.[84]

Air operations

On 26 July 37 British fighters engaged fifty Albatros scouts near Polygon Wood. During the mêlée, four German reconnaissance aircraft were able to slip over the line and reconnoitre. Next evening eight British aircraft over Menin lured about twenty Albatros scouts to Polygon Wood, where 59 British fighters were waiting. Allied and German aircraft in the vicinity joined in the dogfight and after an hour the surviving German aircraft withdrew. The British decoys shot down six German aircraft and the ambushers another three while the British lost two aircraft.[85] On 27 July a British reconnaissance aircraft detected an apparent German tactical withdrawal, which enabled XIV Corps to occupy 3,000 yards (2,700 m) of the German front line. Next day the fine weather allowed the British to conduct a large amount of air observation for counter-battery fire and to detect numerous German batteries which had been moved.[86] By 31 July, the Allied air concentration from the Lys River to the sea consisted of 840 aircraft, 330 being fighter aircraft.[53] The French contribution comprised three Groupes de Chasse (fighter groups) including Groupe de Combat 12 (Les Cigognes) of four escadrilles, two bomber squadrons, three artillery observation squadrons and seven observation balloons.[54] Operations to deprive the Germans of air observation over the attack front were curtailed by poor weather on 29 and 30 July. On 31 July, low cloud returned and stopped the air operation in support of the ground offensive. Small numbers of aircraft were sent out to seek targets of opportunity and a small amount of contact patrolling was managed at very low level, giving some information about the progress of the ground battle and leaving thirty British aircraft damaged by bullets and shells.[87]

German 4th Army

At noon the advance on the II Corps front had been stopped by the local German defenders and their artillery. The arrival of the British advance further north on the green line, 500 yards (460 m) beyond the Steenbeek on the XIX Corps front at about 11:00 a.m. took a long time to be communicated to the British divisional headquarters because of mist, slow going by runners, cut signal cables and poor reconnaissance results from contact-patrol aircraft, caused by troops being unwilling to light flares while overlooked by German defences. Around 3:00 p.m. Gough ordered all XIX Corps troops to advance to the green line, in support of the three brigades which had reached it. Delays persisted and a German force approaching from behind the Broodseinde–Passchendaele ridge was not seen by British aircraft. A message from a ground observer did not reach 15th Division headquarters until 12:53 p.m. and rain began soon after, cutting off the view of advanced British troops by artillery observers.[88]

A German creeping barrage began at 2:00 p.m. along XIX Corps front, then German troops attacked the flanks of the most advanced British positions. The 39th Division was pushed back to St Julien, exposing the left of the 55th Division, just as it was attacked frontally over the Zonnebeke spur by six waves of German infantry, preceded by a barrage and three aircraft which bombed and machine-gunned British troops. Attempts to hold the ground between the black and green lines failed due to the communication breakdown, the speed of the German advance and worsening visibility as the rain increased during the afternoon. The 55th and 15th division brigades beyond the black line, were rolled up from north to south and either retreated or were overrun. It took until 6:00 p.m. for the Germans to reach the Steenbeek, as the downpour added to the mud and flooding in the valley. When the Germans were 300 yards (270 m) from the black line, the British stopped the German advance with artillery and machine-gun fire.[89]

The success of the British advance in the centre of the front caused serious concern to the Germans.[90] The defensive system was designed to deal with some penetration but it was meant to prevent the 4,000-yard (3,700 m) advance that XVIII and XIX Corps had achieved. German reserves from the vicinity of Passchendaele, had been able to begin their counter-attack at 11:00–11:30 a.m. when the three British brigades facing the counter-attack by regiments of the German 221st and 50th Reserve Divisions of Group Ypres, were depleted and thinly spread. The British brigades could not communicate with their artillery due to the rain and because the Germans also used smoke shell in their creeping barrage. The German counter-attack was able to drive the British back from the green line along the Zonnebek–Langemarck road, pushing XIX Corps back to the black line. The Germans also recaptured St Julien just west of the green line on the XVIII Corps front,[76] where the counter-attack was stopped by mud, artillery and machine-gun fire.[91] The three most advanced British brigades had lost 70 percent casualties by the time they had withdrawn from the green line.[92]

On the flanks of the Entente attack, German counter-attacks had little success. In the XIV Corps area, German attacks made no impression against British troops, who had had time to dig in but managed to push back a small bridgehead of the 38th Division from the east bank of the Steenbeek, after having suffered heavy losses from British artillery, when advancing around Langemarck. The Guards Division north of the Ypres–Staden railway held its ground; the French repulsed the Germans around St Janshoek and followed up to capture Bixschoote.[93] German counter-attacks in the afternoon against II Corps on the Gheluvelt plateau, intended to recapture Westhoek Ridge, were able to advance a short distance from Glencorse Wood, before the 18th Division artillery and a counter-attack pushed them back again. In the Second Army area south of the plateau at La Basse Ville, a powerful attack at 3:30 p.m. was repulsed by the New Zealand Division. X Corps also managed to hold its gains around Klein Zillibeke against a big German attack at 7:00 p.m.[94]

Aftermath

Analysis

On 4 August, Haig claimed to the Cabinet that the attack was a success and that casualties had been low for such a big battle, 31,850 men from 31 July – 2/3 August, compared to 57,540 losses on 1 July 1916. An advance of about 3,000 yards (2,700 m) had been achieved, German observation areas on the highest part of the Gheluvelt Plateau near "Clapham Junction", the ridge from Bellewaarde to Pilckem had been captured and nine German divisions had been "shattered" and hurriedly relieved by the first echelon of Eingreif Divisions, implying that fresh divisions had replaced them in turn, beginning the process of drawing German divisions to Flanders, away from the bulk of the French armies. An unusually large number of German dead were counted, more than 6,000 prisoners and 25 guns had been taken. The nine attacking Fifth Army divisions, had been intended to gain the green line and possibly parts of the red line and then be capable of pressing on to the Passchendaele–Staden Ridge in a later attack, before needing to be relieved. The green line had been reached in the north but only part of the black line in the south on the Gheluvelt Plateau, at a cost of 30–60 percent casualties and about half of the tanks engaged had been knocked out or bogged down.[95]

The defensive power of the German Eingreif Divisions had been underestimated and the attacking divisions, having easily advanced for 1 mi (1.6 km) in three hours, had been exposed to observed machine-gun and artillery-fire for the rest of the day, most of the British casualties being incurred after the advance. The postponements of the attack prolonged the preliminary bombardment for six days and wet ground, particularly in the Bassevillebeeek, Hanebeek and Steeenbeek valleys had become crater-fields that filled with water when it rained. The German artillery concentration behind the Gheluvelt Plateau had been most effective against the artillery of the II and XIX corps, firing high-explosive and mustard gas bombardments, which caused many casualties to the British gunners, who could not be rested during the preparatory period, firing a record amount of ammunition but having to distribute it as far back as Flandern I.[96][lower-alpha 4]

In 1996, Prior and Wilson wrote that the French First Army, XIV Corps, XVIII Corps and XIX Corps advanced about 3,000 yards (2,700 m) took two German defensive positions and deprived the Germans of their observation posts on Pilckem Ridge, a "substantial achievement" despite the later repulse of the XVIII and XIX corps from the areas of the green and red lines. II Corps on the Gheluvelt Plateau had only advanced about 1,000 yards (910 m) beyond the Albrecht Stellung but took Bellewaarde Ridge and Stirling Castle. The training of the Fifth Army troops had enabled them to use Lewis guns, rifle grenades, trench mortars and tanks to overwhelm German pill boxes, where the artillery had managed to neutralise the defenders of a sufficient number in advance. Casualties were about the same, unlike 1 July 1916 when the British had only inflicted a few thousand on the Germans. The Fifth Army captured about 18 square miles (47 km2) on 31 July compared to only 3.5 square miles (9.1 km2) on the First day of the Somme.[98]

The German defensive success on the Gheluvelt Plateau left the British in the centre open to enfilade-fire from the right, that contributed to the higher number of losses after the advance had stopped and Gough was criticised for setting objectives that were too ambitious, causing the infantry to lose the barrage and become vulnerable to the German afternoon counter-attacks. Prior and Wilson wrote that the failure had deeper roots, since successive attacks could only be spasmodic, as guns were moved forward, a long process that would only recover the ground lost in 1915. This was far less than the results Haig had used to justify the offensive, in which great blows would be struck, the German defences would collapse and the British would be able safely to advance beyond the range of supporting artillery to the Passchendaele and Klercken ridges, towards Roulers and Thourout and the Belgian coast. The German counter-bombardments and Eingreif divisions had not crumpled, leaving only the possibility of a slow tactical success, rather than a strategic triumph.[99]

In 2008, Harris called the attack on 31 July a remarkable success compared to 1 July 1916, with only about half the casualties and far fewer fatalities, inflicting about the same number on the Germans, prisoner interrogations convincing Haig that the German army had deteriorated. The relative failure on the Gheluvelt Plateau and the repulse in the centre from the red line and parts of the green line by German counter-attacks did not detract from this, other counter-attacks being defeated. Had the weather been dry during August the German defence might have collapsed and the geographical objective of the offensive, to re-capture the Belgian coast might have been achieved. Much rain fell on the afternoon of 31 July and the rain in August was unusually severe, having a worse effect on the British, who had more artillery and a greater need to get artillery-observation aircraft into action in the conditions of rain and low cloud. Mud paralysed manoeuvre and the Germans were trying to hold ground rather than advance, that was an easier task regardless of the weather.[100]

Casualties

The British Official History recorded Fifth Army casualties for 31 July – 3 August as 27,001, of whom 3,697 were killed.[101] Second Army casualties 31 July – 2 August were 4,819 with, 769 killed. The 19th Division lost 870 casualties.[102] German 4th Army casualties for 21–31 July were c. 30,000 men. J. E. Edmonds the British official historian, added another 10,000 lightly wounded to the total, practice which has been questioned ever since.[101][103][104] in 2014, Greenhalgh recorded 1,300 French losses in I Corps.[49] According to Albrecht von Thaer, a staff officer at Group Wytschaete, units may have survived physically but no longer had the mental ability to continue.[105] In 1931, Gough wrote that 5,626 prisoners had been taken.[106]

Subsequent operations

German artillery kept up a heavy fire on the new British front line and along with the rain caused great difficulty in consolidating the captured ground.[94] In the Second Army area, on 1 August, a German counter-attack on the front of the 3rd Australian Division reached the Warneton Line, before being stopped by artillery and machine-gun fire. A planned attack by the 19th and 39th divisions on 3 August, to regain the portion of the first objective (blue line) was cancelled when a battalion moved forward and occupied the ground unopposed. The 41st Division captured Forret Farm on the night of 1/2 August and the 19th Division pushed observation posts forward to the blue line.[102] Operation Sommernacht, a German Stormtroop (Stoßtrupp) attack, took place on 5 August at 5:00 a.m., on the front of the 41st Division in the X Corps area. Hollebeke village was captured and posts established near Forret Farm, under cover of a heavy and accurate artillery bombardment in thick mist. British SOS flares were too wet to light, the barrage cut the telephone lines and visual signalling failed.[107]

About 100 Stormtroops rushed Forret Farm and a nearby trench. Three posts were organised by the neighbouring 19th Division battalion, that counter-attacked the Germans from three directions, despite the Germans getting a machine-gun into action. As the British approached the farm, about fifty of the Germans tried to surrender but then lay down and resumed firing. The Germans retreated as the farm was rushed and some prisoners were taken; patrols then followed the German troops and took more prisoners. At about 9:00 a.m. the mist had suddenly lifted and revealed a force of about 200 German Stoßtruppen near "The Twins", which was engaged with small-arms fire and then scattered by artillery-fire. The position was handed over to the 41st Division by 11:00 a.m. and more German attacks on 6 August, failed to reach the village.[108]

On the Fifth Army front, a German counter-attack on the boundary of the II and XIX Corps, managed to push back the 8th Division for a short distance, south of the Ypres–Roulers railway. North of the line the 15th Division stopped the attack with artillery-fire and two battalions of the 8th Division counter-attacked and restored the original front line by 9:00 p.m. The Germans renewed the attack on the 15th and 55th divisions in the afternoon of 2 August and were repulsed from the area around Pommern Redoubt. A second attempt at 5:00 p.m. was "crushed" by artillery-fire, the Germans retiring behind Hill 35. German troops reported in Kitchener's Wood opposite the 39th Division were bombarded, St. Julien was occupied and posts established across the Steenbeek, north of the village; more advanced posts were established by the 51st Division on 3 August.[107]

A German attack on 5 August recaptured part of Jehovah Trench from the 24th Division in the II Corps area, before being pushed out next day. On 7 August, the Germans managed to blow up a bridge over the Steenbeek, at Chien Farm in the 20th Division area. On the night of 9 August, the 11th Division in the XVIII Corps area, took the Maison Bulgare and Maison du Rasta pillboxes unopposed and pushed posts on the far side of the Steenbeek another 150 yards (140 m) forward.[109] An attempt by the 11th Division to gain more ground was stopped by fire from Knoll 12 and the 29th Division in the XIV Corps area, took Passerelle Farm and established posts east of the Steenbeek, building twelve bridges across the river. The neighbouring 20th Division, inched forward on 13 August and attacked again on 14 August across the Steenbeek. Mill Mound and four "Mebu" (Mannschafts–Eisenbeton–Unterstände) shelters were captured but the attacking troops had to dig in short of the Au Bon Gite blockhouse, repulsing a German counter-attack next day.[110]

Capture of Westhoek

The preliminary operation on the Gheluvelt Plateau intended for 2 August was delayed by rain until 10 August and the general offensive due on 4 August was postponed to 16 August.[lower-alpha 5] II Corps attacked on 10 August, to take the part of the black line not captured on 31 July. British artillery-fire was distributed across the battlefront for the general attack of the Fifth and First French armies, to the green line just east of the German Wilhelm (third) line, between Polygon Wood and Langemarck and for the crossing of the Steenbeek further north. The German artillery could concentrate on the II and XIX Corps fronts and ignore the threat further north. British counter-battery efforts were hampered by low cloud and rain, that made air observation extremely difficult. Much of the British counter-battery effort was wasted, because German artillery shifted position and bombardments fell on empty emplacements.[lower-alpha 6] The 8th and 30th Divisions had been relieved by 25th and 18th Divisions by 4 August but postponements caused by the rain, meant that reliefs of the front-line troops every 48 hours exhausted all of the battalions in the divisions by 10 August.[111]

On 10 August, an attack by the 24th Division on Lower Star Post failed, after German sentries caught sight of the British troops assembling in the moonlight.[112] The principal advance was made by the 18th Division in the centre and succeeded quickly but German artillery began a SOS barrage at 6.00 a.m., from Stirling Castle to Westhoek, that isolated the foremost infantry beyond Inverness Copse and in Glencorse Wood, as local German reserves began immediate counter-attacks. Around 7:00 p.m., German infantry advanced behind a smokescreen and recaptured the Copse and all but the north-west corner of Glencorse Wood.[113] The 74th Brigade of the 25th Division advanced at 4:25 a.m., fast enough to evade the German barrage on the British front line and reached its objectives by 5:30 a.m., assisted by the fire power of five Royal Field Artillery brigades.[114] The German garrison of Westhoek was rushed, while on the right flank, sniping and attacks by German aircraft caused a considerable number of casualties during the day. The division held its gains around Westhoek but lost 158 killed, 1,033 wounded and more than 100 missing. The difficulties encountered by the 18th Division in Glencorse Wood on the right, as it was pushed back towards its start line, allowed German snipers and machine-gun fire to obstruct consolidation in the 25th Division area, particularly on the right flank, as the German troops reoccupied positions lost earlier in the day.[114]

During the day and night of 10/11 August, the Germans made several attempts to counter-attack the 25th Division. Excellent liaison by SOS signal, daylight lamps, pigeons and runners, made British artillery-fire highly accurate on the German counter-attack troops in their assembly positions, preventing the attacks, except for one at 7:15 p.m. that was repulsed by rifle and machine-gun fire.[115] The 25th Division gains on Westhoek Ridge were held and by 14 August, the attacking troops had been relieved by the 56th and 8th divisions.[116] Next day a small German attack at 4:30 a.m. retook a pillbox from the 8th Division, which was recaptured shortly after.[110] At dawn on 10 August, the French First Army attacked in the Bixschoote area and advanced between the Yser Canal and the lower reaches of the Steenbeek. The west bank of the inundations was occupied and in several places the Steenbeek was crossed. Five guns were captured and with the French close to Merckem and over the Steenbeek near St. Janshoek, the German defences at Drie Grachten and Langemarck were outflanked from the north-west.[117]

Notes

- ↑ The ground conditions were such that only 19 tanks reached the German second line.[37]

- ↑ Twelve brigades of field artillery supported each division, that brought the artillery support available to II Corps to approximately 1,000 guns.[43]

- ↑ The Eingreif divisions were not needed.

- ↑ Major-General Hugh Trenchard, commander of the RFC, wrote to the ground commanders after the battle, that a study of low-flying attacks on German troops concluded that the effect was short-lived, though highly demoralising for the victims and equally stimulating to friendly infantry in the vicinity. Trenchard wrote that such attacks would have best effect when co-ordinated with ground operations.[97] Trenchard emphasised that the infantry should be told that much of the air effort took place out of sight and that absence of British aircraft over the battlefield should not be taken for inactivity. Rain continued until 5 August and seriously interrupted artillery observation flying.[97]

- ↑ 59.1 mm of rain fell from 1–10 August, including 8 mm in a thunderstorm on 8 August.[63]

- ↑ The state of the ground, German artillery-fire and British artillery losses foreshadowed the situation in late October opposite Passchendaele ridge.[111]

Footnotes

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 12–15.

- ↑ Falls 1940, p. 21.

- ↑ Hart & Steel 2001, p. 30.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, p. 29.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 29.

- ↑ Keegan 1998, pp. 348–349.

- ↑ Sheffield 2011, p. 231.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 9.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 25.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, p. 284.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 45–47.

- ↑ Sheffield 2011, p. 227.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 20, 126–127.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 126–127, 431–432.

- ↑ Greenhalgh 2014, pp. 231–233.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 124.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, p. 80.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, pp. 72–75.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 143–144.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 431–432.

- ↑ Simpson 2001, p. 117.

- ↑ Davidson 1953, p. 29.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 436–439.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 440–442.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 129.

- ↑ The Times 1918, p. 336.

- ↑ Jones 1934, p. 145.

- ↑ Jones 1934, p. 156.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 132.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, p. 86.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 133.

- ↑ Bean 1941, p. 697.

- ↑ Bax & Boraston 1926, p. 127.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 432.

- ↑ Harris 1995, p. 102.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 79–82.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 83, 80.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, pp. 287–299.

- ↑ Beach 2005, pp. 212–213.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 131–132.

- 1 2 Nichols 1922, p. 204.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 153, 433–436.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, map 10.

- ↑ Greenhalgh 2014, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 109.

- ↑ The Times 1918, p. 335.

- 1 2 Greenhalgh 2014, p. 233.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 127, maps 10, 12, 15.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 180, 186, App XVII, map 17; 190 App XVII, maps 18, 19.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 143.

- 1 2 Jones 1934, p. 141.

- 1 2 Greenhalgh 2014, p. 232.

- ↑ Lupfer 1981, p. 14.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, p. 288.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, pp. 288–289.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, p. 292.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1948, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Wyrall 1932, pp. 97–101.

- ↑ Wyrall 1932, pp. 101–104.

- ↑ Miles 1920, pp. 174–176.

- 1 2 McCarthy 1995, pp. 7–39.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 89.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1948, p. 153.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, p. 57.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Bax & Boraston 1926, p. 136.

- ↑ Bax & Boraston 1926, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 154–156.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 92.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 157–169.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Headlam 1924, pp. 239–240.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1948, map 13.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 90.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 163.

- ↑ The Times 1918, p. 337.

- ↑ The Times 1918, p. 339.

- ↑ The Times 1918, p. 340.

- ↑ The Times 1918, p. 351.

- ↑ The Times 1918, p. 353.

- ↑ Jones 1934, p. 158.

- ↑ Jones 1934, pp. 159–162.

- ↑ Jones 1934, pp. 160–162.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 169.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 173.

- ↑ Harris 2008, p. 366.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 173–174.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 174.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1948, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 177–179.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 179–180.

- 1 2 Jones 1934, pp. 167–168.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 96.

- ↑ Harris 2008, pp. 366–368.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1948, p. 178.

- 1 2 Wyrall 1932, p. 104.

- ↑ McRandle & Quirk 2006, pp. 667–701.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, p. 312.

- ↑ Liddle 1998, pp. 45–58.

- ↑ Gough 1968, p. 200.

- 1 2 McCarthy 1995, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ McCarthy 1995, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ McCarthy 1995, pp. 34–36.

- 1 2 McCarthy 1995, pp. 43–45.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1948, p. 184.

- ↑ McCarthy 1995, p. 39.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 188.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1948, p. 189.

- ↑ Kincaid-Smith 1920, pp. 87–93.

- ↑ Kincaid-Smith 1920, p. 93.

- ↑ The Times 1918, p. 354.

References

- Books

- Bax, C. E. O.; Boraston, J. H. (2001) [1926]. Eighth Division in War 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Medici Society. ISBN 1-897632-67-3.

- Bean, C. E. W. (1941). The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. IV (1982 ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 0-70221-710-7.

- Davidson, J. H. (2010) [1953]. Haig: Master of the Field (Pen & Sword ed.). London: Peter Nevill. ISBN 1-84884-362-3.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1992) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-90162-775-5.

- Falls, C. (2001) [1940]. Military Operations: France and Belgium 1917: The German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line and the Battles of Arras. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-180-6.

- Gough, H. de la P. (1968) [1931]. The Fifth Army (repr. Cedric Chivers ed.). London: Hodder & Stoughton. OCLC 59766599.

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth (2014). The French Army and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60568-8.

- Harris, J. P. (1995). Men, Ideas and Tanks: British Military Thought and Armoured Forces, 1903–1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4814-1.

- Harris, J. P. (2008). Douglas Haig and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89802-7.

- Hart, P.; Steel, N. (2001). Passchendaele: the Sacrificial Ground. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35975-0.

- Headlam, C. (2001) [1924]. History of the Guards Division in the Great War 1915–1918. I (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 1-84342-124-0.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1934]. The War in the Air Being the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force (PDF). IV (Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 1-84342-415-0. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- Keegan, J. (1998). The First World War. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6645-1.

- Kincaid-Smith, M. (2001) [1920]. The 25th Division in France and Flanders (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Harrison. ISBN 1-84342-123-2.

- Liddle, P., ed. (1998). Passchendaele in Perspective: the Third Battle of Ypres. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 0-85052-588-8.

- Lupfer, T. (1981). The Dynamics of Doctrine: The Change in German Tactical Doctrine During the First World War (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, KS: U. S. Army Command and General Staff College. OCLC 227541165. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- McCarthy, C. (1995). The Third Ypres: Passchendaele, the Day-By-Day Account. London: Arms & Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-217-0.

- Miles, W. (2009) [1920]. The Durham Forces in the Field 1914–18, The Service Battalions of the Durham Light Infantry (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 1-84574-073-4.

- Nichols, G. H. F. (2004) [1922]. The 18th Division in the Great War (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Blackwood. ISBN 1-84342-866-0.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (1996). Passchendaele: The Untold Story. Cumberland: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07227-9.

- Sheffield, G. (2011). The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-691-8.

- Sheldon, J. (2007). The German Army at Passchendaele. London: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 1-84415-564-1.

- Terraine, J. (1977). The Road to Passchendaele: The Flanders Offensive 1917, A Study in Inevitability. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-436-51732-9.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, NY ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-8371-5029-9.

- Wyrall, E. (2009) [1932]. The Nineteenth Division 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 1-84342-208-5.

- Encyclopaedias

- The Times History of the War (PDF). XV. London: The Times. 1914–1921. OCLC 642276. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- Journals

- McRandle, J. H.; Quirk, J. (July 2006). "The Blood Test Revisited: A New Look at German Casualty Counts in World War I". 70 (3). Lexington Va: The Journal of Military History: 667–701. doi:10.1353/jmh.2006.0180. ISSN 0899-3718. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Theses

- Beach, J. (2005). British Intelligence and the German Army, 1914–1918 (PhD). uk.bl.ethos.416459. London: London University. OCLC 500051492. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- Simpson, A. (2001). The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18 (Thesis). uk.bl.ethos.367588. London: University of London. OCLC 557496951. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Pilckem Ridge. |

- Order of Battle – France and Flanders 1917, Battle # 98 – Order of Battle for the Battle of Pilckem Ridge

- C. E. W. Bean, The Australian Imperial Force Volume IV, 1917 (The Australian Official History)