Beauvais Cathedral

| Cathedral of Saint Peter of Beauvais Cathédrale Saint Pierre | |

|---|---|

Beauvais Cathedral from SE. | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Beauvais, France |

| Geographic coordinates | 49°25′57″N 2°04′53″E / 49.4326°N 2.0814°ECoordinates: 49°25′57″N 2°04′53″E / 49.4326°N 2.0814°E |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Province | Diocese of Beauvais |

| Region | Picardy |

| Year consecrated | 1272[1] |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Cathedral |

| Status | Active |

| Heritage designation | 1840 |

| Leadership | Jacques Benoit-Gonnin[2] |

| Website |

www |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) |

Enguerrand Le Riche Martin Chambiges[1] |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Architectural style | French Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1225[1] |

| Completed | Never completed. Works halted in 1600.[1] |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 72.5 metres (238 ft) |

| Width | 67.2 metres (220 ft) |

| Width (nave) | 16 metres (52 ft) |

| Height (max) | 48.5 metres (159 ft) (nave) |

| Official name: Cathédrale Notre-Dame | |

| Designated | 1840 |

| Reference no. | PA00114502[1] |

| Denomination | Église |

The Cathedral of Saint Peter of Beauvais (French: Cathédrale Saint-Pierre de Beauvais) is an incomplete Roman Catholic cathedral in Beauvais, in northern France. Constructed from the 13th-century onwards, it is the seat of the Bishop of Beauvais, Noyon and Senlis. Of the Gothic style, it consists only of a transept (16th-century) and choir, with apse and seven polygonal apsidal chapels (13th-century), which are reached by an ambulatory.

A small Romanesque church dating back to the 10th-century, known as the Basse Œuvre, still occupies the site destined for the nave of the Beauvais Cathedral.

History

%2C_Beauvais%2C_France%2C_n.d.._(2788174368).jpg)

Work was begun in 1225 under count-bishop Milo of Nanteuil, with funding of his family, immediately after the third in a series of fires in the old wooden-roofed basilica, which had reconsecrated its altar only three years before the fire; the choir was completed in 1272, in two campaigns, with an interval (1232–38) owing to a funding crisis provoked by a struggle with Louis IX. The two campaigns are distinguishable by a slight shift in the axis of the work and by what Stephen Murray characterizes as "changes in stylistic handwriting."[3] Under Bishop Guillaume de Grez,[4] an extra 4.9 m was added to the height, to make it the highest-vaulted cathedral in Europe. The vaulting in the interior of the choir reaches 48 m (157.48 feet) in height, far surpassing the concurrently constructed Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Amiens, with its 42-metre (138 ft) nave. (A formerly often-quoted beginning date of 1247 was based on an error made by an early historian of Beauvais.[5])

The work was interrupted in 1284 by the collapse of some of the vaulting of the recently completed choir. This collapse is often seen as a disaster that produced a failure of nerve among the French masons working in Gothic style; modern historians have reservations about this deterministic view. Stephen Murray notes that the collapse also "ushers in the age of smaller structures associated with demographic decline, the Hundred Years War, and of the thirteenth century."[6]

However, large-scale Gothic design continued, and the choir was rebuilt at the same height, albeit with more columns in the chevet and choir, converting the vaulting from quadripartite vaulting to sexpartite vaulting.[7] The transept was built from 1500 to 1548. In 1573, the fall of a too-ambitious 153-m (502 feet) central tower stopped work again. The tower would have made the church the tallest structure in the world at the time. Afterwards little structural addition was made.

The choir has always been wholeheartedly admired: Eugène Viollet-le-Duc called the Beauvais choir "the Parthenon of French Gothic."

Its façades, especially that on the south, exhibit all the richness of the late Gothic style. The carved wooden doors of both the north and the south portals are masterpieces, respectively, of Gothic and Renaissance workmanship. The church possesses an elaborate astronomical clock in neo-Gothic taste (1866) and tapestries of the 15th and 17th centuries, but its chief artistic treasures are stained glass windows of the 13th, 14th, and 16th centuries, the most beautiful of them from the hand of Renaissance artist Engrand Le Prince, a native of Beauvais. To him also is due some of the stained glass in St-Etienne, the second church of the town, and an interesting example of the transition stage between the Gothic and the Renaissance styles.

During the Middle Ages, on January 14, the Feast of Asses was annually celebrated in Beauvais cathedral, in commemoration of the Flight into Egypt.

Structural condition

|

Beauvais Cathedral from the east. |

Plan image of Beauvais Cathedral, derived from laser scan data collected in 2007 by nonprofit CyArk to assist in stabilization of the building |

Lateral supports of flying buttresses. |

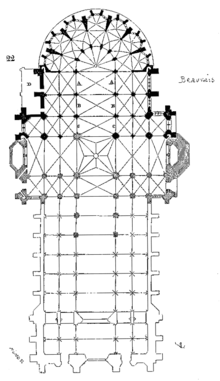

Floorplan; lightest section, nave (never constructed). |

In the race to build the tallest cathedral in the 13th century, the builders of Saint-Pierre de Beauvais pushed the technology to the limits. Even though the structure was to be taller, the buttresses were made thinner in order to pass maximum light into the cathedral. In 1284, only twelve years after completion, part of the choir vault collapsed, along with a few flying buttresses. It is now believed that the collapse was caused by resonant vibrations due to high winds.[8]

The accompanying photograph shows lateral iron supports between the flying buttresses; it is not known when these external tie rods were installed. The technology would have been available at the time of the initial construction, but the extra support might not have been considered necessary until after the collapse in 1284, or even later. In the 1960s, the tie rods were removed; the thinking was that they were disgraceful and unnecessary. However, the oscillations created by the wind became amplified, and the choir partially disassociated itself from the transept. Subsequently, the tie rods were reinstalled, but this time with rods made of steel. Since steel is less ductile than iron, the structure became more rigid, possibly causing additional fissures.[9]

As the floor plan shows, the original design included a nave that was never built. Thus, the absence of shouldering support that would have been contributed by the nave contributes to the structural weakness of the cathedral.

With the passage of time, other problems surfaced, some requiring more drastic remedies. The north transept now has four large wood-and-steel lateral trusses at different heights, installed during the 1990s to keep the transept from collapsing (see photograph). In addition, the main floor of the transept is interrupted by a much larger brace that rises out of the floor at a 45-degree angle.[10] This brace was installed as an emergency measure to give additional support to the pillars that, until now, have held up the tallest vault in the world.

These temporary measures will remain in place until more permanent solutions can be determined. Various studies are under way to determine with more assurance what can be done to preserve the structure. Columbia University is performing a study on a three-dimensional model constructed using laser scans of the building in an attempt to determine the weaknesses in the building and remedies.[11]

Interior

Several of the chapels contain medieval stained glass windows made during the 13th through 15th centuries. In a chapel close to the northern entrance, there is a medieval clock (14th – 15th century), probably the oldest fully preserved and functioning mechanical clock in Europe. In its vicinity, a highly complicated Beauvais Astronomical clock with moving figures was installed in 1866.

The choir. |

Interior supports of north transept. |

Stained glass windows |

Medieval clock |

Astronomical clock (1866) |

See also

References

- Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mérimée database 1993

- ↑ Catholic-hierarchy.org 2011

- ↑ Murray 1980:547.

- ↑ William of Grez was the first bishop to be buried in the axial Lady Chapel, 1267.

- ↑ Murray 1980:533 note 5.

- ↑ Murray 1980:533.

- ↑ Cruickshank, Dan, ed. (1996). Sir Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture (20th ed.). Architectural Press. p. 436. ISBN 0-7506-2267-9.

- ↑ Découvrir la Cathedrale Saint-Pierre de Beauvais, Philippe Bonnet-Laborderie, 2000

- ↑ Stephen Murray, Beauvais Cathedral, Architecture of Transcendence, Princeton University Press, 1989

- ↑ Structurae [en]: Images: ID 43432

- ↑ The Beauvais Cathedral Project

- Bibliography

- "Monument historique — PA00114502". Mérimée database of Monuments Historiques (in French). France: Ministère de la Culture. 1993. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Cheney, David M. "Diocese of Beauvais (-Noyon-Senlis)". The Hierarchy of the Catholic Church - Current and historical information about its bishops and dioceses. Catholic-hierarchy.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- Murray, Stephen: "The Choir of the Church of St.-Pierre, Cathedral of Beauvais: A Study of Gothic Architectural Planning and Constructional Chronology in Its Historical Context", The Art Bulletin 62.4 (December 1980), pp. 533–551

- Plouvier, Martine, ed. (2000). La cathédrale Saint-Pierre de Beauvais : architecture, mobilier et trésor (in French). Amiens: Association pour la généralisation de l'Inventaire régional en Picardie. ISBN 2-906340-42-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beauvais Cathedral. |

- Cathedral of Beauvais Digital Media Archive (creative commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas), data from a World Monuments Fund/CyArk research partnership

- Becher, Peter Karl; Howland, Matthew Barnett (September 2010). "Completing Beauvais Cathedral" (PDF). Architectural Association School of Architecture.

- 360 degrees panorama virtual tour of some French cathedrals including Beauvais

- Photographs and drawings of the cathedral

- Spectacular views of the inside

- Google Earth view of Beauvais Cathedral from south

- Google Earth view of (truncated) west end of Beauvais Cathedral and Basse Oeuvre