Bell

|

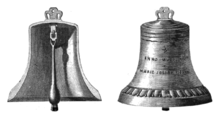

Parts of a typical tower bell hung for swinging: 1. yoke, or headstock 2. canons, 3. crown, 4. shoulder, 5. waist, 6. sound bow, 7. lip, 8. mouth, 9. clapper, 10. bead line | |

| Percussion instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | struck idiophone |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification |

111.242 (Bells: Percussion vessels with the vibration weakest near the vertex) |

| Playing range | |

| From very high to very low | |

| Related instruments | |

| Chimes, Cowbell, Handbell, Gong | |

A bell is a simple idiophone percussion instrument. Although bells come in many forms, most are made of metal cast in the shape of a hollow cup, whose sides form a resonator which vibrates in a single tone upon being struck. The strike may be made by a "clapper" or "uvula" suspended within the bell, by a separate mallet or hammer, or—in small bells—by a small loose sphere enclosed within the body of the bell.

Bells are usually made by casting metal, but small bells can also be made from ceramic or glass. Bells range in size from tiny dress accessories to church bells 5 metres tall, weighing many tons.

Historically, bells have been associated with religious rituals, and are still used to call communities together for religious services.[1] Later, bells were made to commemorate important events or people and have been associated with the concepts of peace and freedom. The study of bells is called campanology.

A set of bells, hung in a circle for change ringing, is known as a ring or peal of bells.

A set of 23 bells spanning at least two octaves is a carillon.

Name

Bell is a word common to the Low German dialects, cognate with Middle Low German belle and Dutch bel but not appearing among the other Germanic languages except the Icelandic bjalla which was a loanword from Old English.[2] It is popularly[3] but not certainly[2] related to the former sense of to bell (Old English: bellan, "to roar, to make a loud noise") which gave rise to bellow.[4]

History

The earliest archaeological evidence of bells dates from the 3rd millennium BC, and is traced to the Yangshao culture of Neolithic China.[5] Clapper-bells made of pottery have been found in several archaeological sites.[6] The pottery bells later developed into metal bells. In West Asia, the first bells appear in 1000 BC.[5]

The earliest metal bells, with one found in the Taosi site and four in the Erlitou site, are dated to about 2000 BC.[7] Early bells not only have an important role in generating metal sound, but arguably played a prominent cultural role. With the emergence of other kinds of bells during the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600 – c. 1050 BC), they were relegated to subservient functions; at Shang and Zhou sites, they are also found as part of the horse-and-chariot gear and as collar-bells of dogs.[8]

See also Klang Bell (Malaysia, 2 c. BC) of the British Museum collection.

Methods of ringing

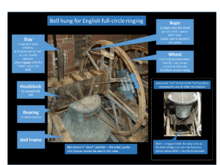

In the western world, the common form of bell is a church bell or town bell, which is hung within a tower or bell cote. Such bells are either fixed in position ("hung dead") or mounted on a beam (the "headstock") so they can swing to and fro. Bells that are hung dead are normally sounded by hitting the sound bow with a hammer or occasionally by pulling an internal clapper against the bell.

Where a bell is swung it can either be swung over a small arc by a rope and lever or by using a rope on a wheel to swing the bell higher. As the bell swings higher the sound is projected outwards rather than downwards.

Bells hung for full circle ringing are swung through just over a complete circle from mouth uppermost. A stay (the wooden pole seen sticking up when the bells are down) engages a mechanism to allow the bell to rest just past its balance point. The rope is attached to one side of a wheel so that a different amount of rope is wound on and off as it swings to and fro. The bells are controlled by ringers (one to a bell) in a chamber below, who rotate the bell to through a full circle and back, and control the speed of oscillation when the bell is mouth upwards at the balance-point, when little effort is required.

Swinging bells are sounded by an internal clapper. The clapper may have a longer period of swing than the bell. In this case the bell will catch up with the clapper and if rung to or near full circle will carry the clapper up on the bell's trailing side. Alternatively, the clapper may have a shorter period and catch up with the bell's leading side, travel up with the bell coming to rest on the downhill side. This latter method is used in English style full circle ringing.

Occasionally the clappers have leather pads (called muffles) strapped around them to quieten the bells when practice ringing to avoid annoying the neighbourhood. Also at funerals, half-muffles are often used to give a full open sound on one round, and a muffled sound on the alternate round – a distinctive, mournful effect.

Church and temple bells

In the Eastern world, the traditional forms of bells are temple and palace bells, small ones being rung by a sharp rap with a stick, and very large ones rung by a blow from the outside by a large swinging beam. (See images of the great bell of Mii-dera below.)

The striking technique is employed worldwide for some of the largest tower-borne bells, because swinging the bells themselves could damage their towers.

In the Roman Catholic Church and among some High Lutherans and Anglicans, small hand-held bells, called Sanctus or sacring bells,[9] are often rung by a server at Mass when the priest holds high up first the host and then the chalice immediately after he has said the words of consecration over them (the moment known as the Elevation). This serves to indicate to the congregation that the bread and wine have just been transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ (see transubstantiation), or, in the alternative Reformation teaching, that Christ is now bodily present in the elements, and that what the priest is holding up for them to look at is Christ himself (see consubstantiation).

In Russian Orthodox bell ringing the entire bell never moves, only the clapper. A complex system of ropes is developed and used uniquely for every bell tower. Some ropes (the smaller ones) are played by hand, the bigger ropes are played by foot.

Bells in Japanese religion

Japanese Shintoist and Buddhist bells are used in religious ceremonies. Suzu, a homophone meaning both "cool" and "refreshing", are spherical bells which contain metal pellets that produce sound from the inside. The hemispherical bell is the Kane bell, which is struck on the outside. Large suspended temple bells are known as bonshō. (See also ja:鈴, ja:梵鐘).

Bells in Buddhism and Hinduism

Hindu and Buddhist bells, called "Ghanta" in Sanskrit, are used in religious ceremonies. See also singing bowls. A bell hangs at the gate of many Hindu temples and is rung at the moment one enters the temple.[10]

Bellfounding

The process of casting bells is called bellfounding, and in Europe dates to the 4th or 5th century.[12] The traditional metal for these bells is a bronze of about 23% tin.[13] Known as bell metal, this alloy is also the traditional alloy for the finest Turkish and Chinese cymbals. Other materials sometimes used for large bells include brass and iron. Steel was tried during the busy church-building period of mid-19th-century England, because it was more economical than bronze, but was found not to be durable and manufacture ceased in the 1870s.[14]

Casting

Small bells were originally made with the lost wax process but large bells are cast mouth downwards by filling the air space in a two-part mould with molten metal. Such a mould has an outer section clamped to a base-plate on which an inner core has been constructed.[15]

The core is built on the base-plate using porous materials such as coke or brick and then covered in loam well mixed with straw and horse manure. This is given a profile corresponding to the inside shape of the finished bell, and dried with gentle heat. Graphite and whiting are applied to form the final, smooth surface.

The outside of the mould is made within a perforated cast iron case, larger than the finished bell, containing the loam mixture which is shaped, dried and smoothed in the same way as the core. The case is inverted (mouth down), lowered over the core and clamped to the base plate. The clamped mould is supported, usually by being buried in a casting pit to bear the weight of metal and to allow even cooling.[16]

In historical times, before road, rail transport of large bells was possible, a "bell pit" was often dug in the grounds of the building where the bell was to be installed. Molten bell metal is poured into the mould through a box lined with foundry sand. The founder would bring his casting tools to the site, and a furnace would be built next to the pit.

Tuning

Bell shape and tuning

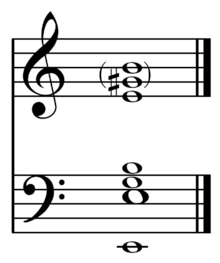

"A bell is divided into the body or barrel, the ear or cannon, and the clapper or tongue. The lip or sound bow is that part where the bell is struck by the clapper."[19] The traditional profile (or shape), hollow cup with wide flaring lip, of a bell is determined by the acoustic properties sought.

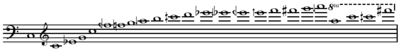

According to Fuller-Maitland writing in Grove's dictionary of music and musicians: "Good tone means that a bell must be in tune with itself."[20] A bell is generally considered well-tuned if it corresponds to certain standards regarding its partials and thus proportions. These partials or elements of the sound of a bell are split up into hum (an octave below the named note, see subharmonic), strike tone (tap note, named note), tierce (minor third), quint (fifth), and nominal (octave). Further notes include the major third and perfect fifth in the second octave. "Whether a founder tunes the nominal or the strike note makes little difference, however, because the nominal is one of the main partials that determines the tuning of the strike note."[21] A heavy clapper brings out lower partials (clappers often being about 3% of a bell's mass), while a higher clapper velocity strengthens higher partials (0.4 m/s being moderate). The relative depth of the "bowl" or "cup" part of the bell also determines the number and strength of the partials in order to achieve a desired timbre.

Bells are generally around 80% copper and 20% tin (bell metal), with the tone varying according to material. Tone and pitch is also affected by the method in which a bell is struck. It will be noticed that Asian large bells are often bowl shaped but lack the lip and are often not free-swinging. Also note the special shape of Bianzhong bells, allowing two tones. The scaling or size of most bells to each other may be approximated by the equation for circular cylinders: f=Ch/D2, where h is thickness, D is diameter, and C is a constant determined by the material and the profile.[22] Previously tuned through chipping, bells are now tuned after casting with vertical lathes by paring out the inside to flatten or edge to sharpen, with sharpening best being avoided.[23]

On the theory that pieces in major keys may better be accommodated, after many unsatisfactory attempts, in the 1980s, using computer modeling for assistance in design by scientists at the Technical University in Eindhoven, bells with a major-third profile were created by the Eijsbouts Bellfoundry in the Netherlands,[21] being described as resembling old Coke bottles[25] in that they have a bulge around the middle;[26] and in 1999 a design without the bulge was announced.[22] Although bells are cast to accurate patterns, variations in casting mean that a final operation of tuning is undertaken as the shape of the bell is critical in producing the desired strike note and associated harmonics. Tuning is undertaken by clamping the bell on a large rotating table, and using a cutting tool to remove metal. Much experimentation and research has been devoted to determining the exact shape that will give the best tone.

The thickness of a church bell at its thickest part, called the "sound bow", is usually one thirteenth its diameter. If the bell is mounted as cast, it is called a "maiden bell". "Tuned bells" are worked after casting to produce a precise note. The elements of the sound of a bell are split up into hum (see subharmonic), second partial, tierce, quint and nominal/naming note. The bell's strongest overtones are tuned to be at octave intervals below the nominal note, but other notes also need to be brought into their proper relationship.[27] Bells are usually tuned via tuning forks and electronic stroboscopic tuning devices commonly called strobe tuners.

Clocks and chimes

Bells are also associated with clocks, indicating the hour by ringing. Indeed, the word clock comes from the Latin word cloca, meaning bell. Bells in clock towers or bell towers can be heard over long distances, which was especially important in the time when clocks were too expensive for widespread use. In many languages the same word can mean both clock and bell.

In the case of clock towers and grandfather clocks, a particular sequence of tones may be played to distinguish between the hour, half-hour, quarter-hour, or other intervals. One common pattern is called "Westminster Quarters," a sixteen-note pattern named after the Palace of Westminster which popularized it as the measure used by Big Ben.

Notable bells

- The Great Bell of Dhammazedi (1484) may have been the largest bell ever made. It was lost in a river in Burma after being removed from a temple by the Portuguese in 1608. It is reported to have weighed about 300 tonnes (330 tons).

- The Tsar Bell by the Motorin Bellfounders is the largest bell still in existence. It weighs 160 tonnes (180 tons), but it was never rung and broke in 1737. It is on display in Moscow, Russia, inside the Kremlin.

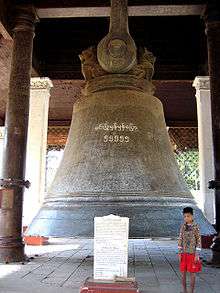

- The Great Mingun Bell is the largest functioning bell. It is located in Mingun, Burma, and weighs 90 tonnes (100 tons).

- The Gotenba Bell is the largest functioning swinging bell, weighing 79,900 pounds (36,200 kg). It is located in a tourist resort in Gotenba, Japan. Hung in a freestanding frame, it is rung by hand. It was cast by Eijsbouts in 2006.

- The World Peace Bell was the largest functioning swinging bell until 2006. It is located in Newport, Kentucky, United States, and was cast by the Paccard Foundry of France. The bell itself weighs 66,000 pounds (30,000 kg); with clapper and supports, the total weight which swings when the bell is rung is 89,390 pounds (40,550 kg).

- The Bell of King Seongdeok is the largest extant bell in Korea. The full Korean name means "Sacred Bell of King Seongdeok the Great." It was also known as the Bell of Bongdeoksa Temple, where it was first housed. The bell weighs about 25 tons and was originally cast in 771 CE. It is now stored in the National Museum of Gyeongju.

- Pummerin in Vienna's Stephansdom is the most famous bell in Austria and the fifth largest in the world.

- The St. Petersglocke, in the local dialect of Cologne also called dä Dicke Pitter ("fat Peter", [ˌdekə.ˈpitˑɐ]), is a bell in Germany's Cologne Cathedral. It weighs 24 tons and was cast in 1922. It is the largest functioning free-swinging bell in the world that swings around the top. (The Gotenba Bell and the World Peace Bell swing around their center of gravity, which is more like turning than swinging. So, depending on the point of view, the St. Petersglocke may be considered up to now the largest free-swinging bell in the world.)

- Maria Dolens, the bell for the Fallen in Rovereto (Italy) weighs 22.6 tons.

- The South West tower of St Paul's Cathedral in London, England, houses Great Paul, the second largest bell at 16.5 tons in the British Isles. One can hear Great Paul booming out over Ludgate Hill at 1300 every day.

- Big Ben is the fourth largest bell in the British Isles, after The Olympic Bell (used at the opening of the 2012 Olympic Games), Great Paul (St Paul's Cathedral, City of London) and Great George (Anglican Cathedral, Liverpool). It is the hour bell of the Great Clock in the Elizabeth Tower (formerly called the Clock Tower) at the Palace of Westminster, the home of the Houses of Parliament in the United Kingdom.

- The Dom Tower in the city of Utrecht, the Netherlands, houses the second largest free-swinging bell of Europe, the Salvator, weighing 8.2 tons and cast in 1505 by Geert van Wou.

- Great Tom is the bell that hangs in Tom Tower (designed by Christopher Wren) of Christ Church, Oxford. It was cast in 1680 and weighs over 6 tons. Great Tom is still rung 101 times at 21:05 every night to signify the 101 original scholars of the college.

- The Liberty Bell is a 2,080 pounds (940 kg)[28] American bell of great historic significance, located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It previously hung in Independence Hall.

- Little John, named after the character from the legends of Robin Hood, is the bell within the Clock Tower of Nottingham Council House. It was the deepest toned clock bell in the United Kingdom until Great Peter of York Minster was incorporated into a new clock chime to celebrate the Queen Mother's centenary. Great Peter is deeper than Little John by only a few Hz. The sound of Little John is said to be heard over the greatest distance of any bell in the UK, occasionally on quiet days being heard in Derby.

- Sigismund is a bell in the Wawel Cathedral in Kraków, Poland, cast in 1520. It is rung only on very significant national occasions.

- The Maria Gloriosa in Erfurt, cast by Geert van Wou, is considered to be one of Germany's, and also Europe's, most beautiful medieval bells, serving as a model for many other bells.

- The Lutine Bell, named after HMS Lutine, weighs 106 pounds (48 kg) and bears the inscription "ST. JEAN – 1779". It rests in Lloyd's of London Underwriting Room where it used to be struck when news of an overdue ship arrived—once for the loss of a ship (i.e., bad news, last in 1979), and twice for her return (i.e., good news, last in 1989).

- The tenor (heaviest bell) of the change-ringing peal at Liverpool Cathedral is the heaviest bell hung for full-circle ringing.

Usage as musical instruments

Some bells are used as musical instruments, such as carillons, (clock) chimes, agogô, or ensembles of bell-players, called bell choirs, using hand-held bells of varying tones. A "ring of bells" is a set of four to twelve or more bells used in change ringing, a particular method of ringing bells in patterns. A peal in changing ringing may have bells playing for several hours, playing 5,000 or more patterns without a break or repetition. They have also been used in many kinds of popular music, such as in AC/DC's "Hells Bells" and Metallica's "For Whom the Bell Tolls".

Ancient Chinese bells

The ancient Chinese bronze chime bells called bianzhong or zhong / zeng (鐘) were used as polyphonic musical instruments and some have been dated at between 2000 and 3600 years old. Tuned bells have been created and used for musical performance in many cultures but zhong are unique among all other types of cast bells in several respects and they rank among the highest achievements of Chinese bronze casting technology. However, the remarkable secret of their design and the method of casting—known only to the Chinese in antiquity—was lost in later generations and was not fully rediscovered and understood until the 20th century.

In 1978 a complete ceremonial set of 65 zhong bells was found in a near-perfect state of preservation during the excavation of the tomb of Marquis Yi, ruler of Zeng, one of the Warring States. Their special shape gives them the ability to produce two different musical tones, depending on where they are struck. The interval between these notes on each bell is either a major or minor third, equivalent to a distance of four or five notes on a piano.[29]

The bells of Marquis Yi—which were still fully playable after almost 2500 years—cover a range of slightly less than five octaves but thanks to their dual-tone capability, the set can sound a complete 12-tone scale—predating the development of the European 12-tone system by some 2000 years—and can play melodies in diatonic and pentatonic scales.[30]

Another related ancient Chinese musical instrument is called qing (磬 pinyin qìng) but it was made of stone instead of metal.

In more recent times, the top of bells in China was usually decorated with a small dragon, known as pulao; the figure of the dragon served as a hook for hanging the bell.

Konguro'o

Konguro'o is a small bell which, like the Djalaajyn, was first used for utilitarian purposes and only later for artistic ones. Konguro'o rang when moving to new places. They were fastened to the horse harnesses and created a very specific "smart" sound background. Konguro'o also hung on the neck of the leader goat, which the sheep herd followed. This led to the association in folk memory between the distinctive sound of konguro'o and the nomadic way of life.

To make this instrument, Kyrgyz foremen used copper, bronze, iron and brass. They also decorated it with artistic carving and covered it with silver. Sizes of the instruments might vary within certain limits, what depended on its function. Every bell had its own timbre.

Chimes

A variant on the bell is the tubular bell. Several of these metal tubes which are struck manually with hammers, form an instrument named tubular bells or chimes. In the case of wind or aeolian chimes, the tubes are blown against one another by the wind.

Lithuanian Skrabalai

The skrabalai is a traditional folk instrument in Lithuania which consists of wooden bells of various sizes hanging in several vertical rows with one or two wooden or metal small clappers hanging inside them. It is played with two wooden sticks. When the skrabalai is moved a clapper knocks at the wall of the trough. The pitch of the sound depends on the size of the wooden trough. The instrument developed from wooden cowbells that shepherds would tie to cows' necks.

Farm bells

Whereas the church and temple bells called to mass or religious service, bells were used on farms for more secular signaling. The greater farms in Scandinavia usually had a small bell-tower resting on the top of the barn. The bell was used to call the workers from the field at the end of the day's work.

In folk tradition, it is recorded that each church and possibly several farms had their specific rhymes connected to the sound of the specific bells. An example is the Pete Seeger and Idris Davies song "The Bells of Rhymney".

Dead bell

In Scotland up until the 19th century it was the tradition to ring a Dead bell, a form of hand bell, at the death of an individual and at the funeral.

Bell organizations

The following organizations promote the study, music, collection and/or preservation and restoration of bells.[31] Nation(s) covered are given in parenthesis.

- The American Bell Association International (United States with foreign chapters)

- Association Campanaire Wallonne asbl (Belgium)

- Associazione Suonatori di Campane a Sistema Veronese (Italy)

- The Australian and New Zealand Association of Bellringers (Australia, New Zealand)

- Beratungsausschuss für das Deutsche Glockenwesen (Germany)

- British Carillon Society (United Kingdom)

- The Central Council of Church Bell Ringers (United Kingdom)

- Handbell Musicians of America (United States, chapter of English Handbell Ringers Association)

- Handbell Ringers of Great Britain (United Kingdom)

- Société Française de Campanologie (France)

- Verband Deutscher Glockengießereien e.V. (Germany)

- World Carillon Federation (multinational)

Gallery

-

The bell within the Clock Tower colloquially known as Big Ben.

-

Mingun Bell weighs 55,555 viss, or 90 tonnes.

-

The World Peace Bell in Kentucky.

-

St. Petersglocke (with person for scale).

-

Bronze jingyun bell cast in the year 711 AD, Xi'an.

-

Chinese bells from the ancient Warring States, Hubei Provincial Museum, Wuhan, China.

-

St. Ulrich, Memmingen

-

Japanese temple bell of the Ryōanji Temple, Kyoto

-

Yongle Bell

-

St Cuileain's Bell from Ireland, 7th-8th Century AD (British Museum)

-

Fire Bell, Glendale, Arizona.

See also

Note, see above: Compare this 19th-century woodblock print with the 21st-century photo-image.

- American Bell Association International

- Bellhop

- Cat bell

- Electronic tuners, used to tune bells

- Glockenspiel

- Handbell

- John Taylor Bellfounders

- Ship's bell

- Veronese bellringing art

- Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Notes

- ↑ "Bell". Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th Edition. 3. University Press. 1910. pp. 687–691. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- 1 2 "bell, n.1", Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1887.

- ↑ EB (1878), p. 536.

- ↑ "bell, v.4", Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1887.

- 1 2 Falkenhausen, Lothar Von (1993). Suspended Music: Chime Bells in the Culture of Bronze Age China. University of California Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-520-07378-4. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

China seems to have produced the earliest bells anywhere in the world... the earliest metal bells may have been derived from pottery prototypes, which seem to go back to the late stage of the Yang-Shao culture (early third millennium BC)

- ↑ Huang, Houming. "Prehistoric Music Culture of China," in Cultural Relics of Central China, 2002, No. 3:18–27. ISSN 1003-1731. pp. 20–27.

- ↑ Falkenhausen (1994), p. 132, Appendix I pp. 329, 342.

- ↑ Falkenhausen (1994), 134.

- ↑ Herrera, Matthew D.Sanctus Bells: Their History and Use in the Catholic Church. San Luis Obispo: Tixlini Scriptorium, 2004. http://www.ewtn.com/library/liturgy/sanctusbells.pdf

- ↑ "Why do Hindus ring bell in temple". Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ "Bell with Saints Peter, Paul, John, and Thomas". The Walters Art Museum.

- ↑ Milham, Willis I. (1945). Time and Timekeepers, pp. 313–18.

- ↑ Cubberly, William H. (1989). "Metals". In Bakerjian, Ramon. Tool and manufacturing engineers handbook. Dearborn, MI: Society of Manufacturing Engineers. pp. 15–38. ISBN 978-0-87263-351-3.

- ↑ Jennings, Trevor (1988). Bellfounding. Princes Risborough, England: Shire. p. 8. ISBN 0-85263-911-2.

- ↑ Jennings (1988: 3; 10)

- ↑ Jennings (1988: 11)

- ↑ Roads, Curtis, ed. (1992). Harvey Jonathan. "Moruos Plango, Vivos Voco: A Realization at IRCAM", The Music Machine, p.92. ISBN 978-0-262-68078-3. Harvey added, "a clearly audible, slow-decaying partial at 347 Hz with a beating component in it. It is a resultant of the various F harmonic series partials that can be clearly seen in the spectrum (5, [6], 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, etc.) beside the C-related partials."

- ↑ Downes, Michael (2009). Jonathan Harvey: Song offerings and White as jasmine, p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7546-6022-4.

- ↑ Beach, Frederick Converse and Rines, George Edwin (eds.) (1907). The Americana, p.BELL-SMITH—BELL. Scientific American. .

- 1 2 John Alexander Fuller-Maitland (1910). Grove's dictionary of music and musicians, p. 615. The Macmillan company. Strike note shown on C. Hemony appears to be the first to propose this tuning.

- 1 2 Neville Horner Fletcher, Thomas D. Rossing (1998). The Physics of Musical Instruments, p. 685. ISBN 978-0-387-98374-5. Cites Schoofs et al., 1987 for major-third bell.

- 1 2 Rossing, Thomas D. (2000). Science of Percussion Instruments, p. 139. ISBN 978-981-02-4158-2.

- ↑ Musical Association (1902), p. 30.

- ↑ Musical Association (1902). Proceedings of the Musical Association, Volume 28, p. 32. Whitehead & Miller, ltd.

- ↑ http://www.cs.yale.edu/~douglas-craig/bells/Basic/what-is-a-carillon.pdf

- ↑ "Major third bell", Andrelehr.nl.

- ↑ Jennings (1988: 21)

- ↑ "The Liberty Bell" (pdf). National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ↑ Alan Thorne & Robert Raymond, Man on the Rim: The Peopling of the Pacific (ABC Books, 1989), pp. 166–67

- ↑ Cultural China website – "Bronze Chime Bells of Marquis Yi"

- ↑ Rama, Jean-Pierre (1993). Cloches de France et d’ailleurs, Le Temps Apprivoisé, pp.229-230. Paris, France. ISBN 2283581583.

References

- Milham, Willis Isbister. (1944). Time and Timekeepers: Including the History, Construction, Care, and Accuracy of Clocks and Watches. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 23271006

- Murdoch, James. (1903). 0-415-15416-2&lr=&client=firefox-a A History of Japan. London: Paul, Trech, Trubner. [re-issued by Routledge, London, 1996. ISBN 978-0-415-15416-1]

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard A. B. (1956). Kyoto: The Old Capital of Japan, 794–1869. Kyoto: The Ponsonby Memorial Society.

- Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). [Siyun-sai Rin-siyo/Hayashi Gahō (1652)]. Nipon o daï itsi ran; ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland.

- http://www.towerbells.org/data/GBGreatBells.html

Further reading

- Fadul, Jose A. Fadul's Encyclopedia of Bells. 2015. Lulu Press. ISBN 978-131-260-110-9

- Willis, Stephen Charles. Bells through the Ages: from the Percival Price Collection = Les Cloches à travers les siècles: provenant du fonds Percival Price. Ottawa: National Library of Canada, 1986. 34 p., ill. with b&w photos. N.B.: Prepared on the occasion of an exhibition of the same title, based on the collection of bell and carillon related material and documentation, of former Dominion Carilloneur (of Canadian Parliament, Ottawa), Percival Price, held at the National Library of Canada (as then named), 12 May to 14 Sept. 1986; some copies come with the guide to the taped dubbings of the recordings played as background music to the displays, as technically prepared by Gilles Saint-Laurent and listed by Stephen Charles Willis, both of the library's Music Division; English and French texts respectively divided into upper and lower portions of each page. ISBN 0-662-54295-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bells. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bells |

| Look up bell in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article Bells. |

- Bells at DMOZ

- Bell recordings of the Basque Country

- 'Bells in Aragón: a traditional means of communication' thesis (Spanish)

-

Haweis, H. R. (1878). "Bell". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (9th ed.).

Haweis, H. R. (1878). "Bell". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (9th ed.).