Canada–United Kingdom relations

|

|

Canada |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic Mission | |

| Canadian High Commission, London | British High Commission, Ottawa |

| Envoy | |

| High Commissioner Janice Charette | High Commissioner Howard Drake |

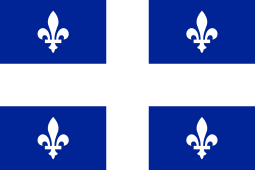

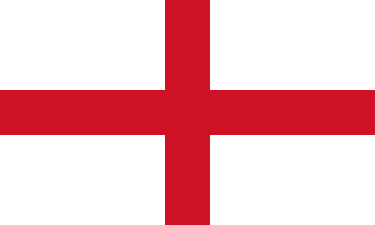

British–Canadian relations are the relations between Canada and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, being bilateral relations between their governments and wider relations between the two societies. The two countries have intimate and frequently cooperative contact; they are related through mutual migration, through shared military history, through a shared system of government, through language, through the Commonwealth of Nations, and their sharing of the same Head of State and monarch. Despite this shared legacy, the two nations have grown apart economically and politically: Britain has not been Canada's largest trading partner since the nineteenth century. Currently Canada and Britain are in different trade blocs, such as NAFTA and the European Union respectively, as well as Britain's independent trade negotiations due to its process of leaving the EU after Brexit.

History

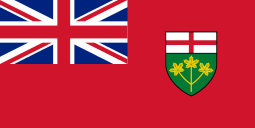

The long-standing relationship between the United Kingdom and Canada formally began in 1867 when the Canadian Confederation fused together the North American British crown colonies of the Province of Canada, Province of New Brunswick and the Province of Nova Scotia. The Dominion of Canada was formed as a Dominion of the British Empire.

The history of relations between Canada and Britain well into the 20th Century is really the story of Canada's slow evolution towards full sovereignty.

British Empire

In 1759, Britain conquered New France, and, after the Treaty of Paris (1763), began to populate formerly-French Canada with English-speaking settlers. British governors ruled these new territories absolutely until the Constitutional Act of 1791, which created the first Canadian legislatures. These weak bodies were still inferior to the governors until the granting of responsible government in 1848. With their new powers, the colonies chose to federate in 1867, creating a new state, Canada, with the new title of Dominion.

The constitution of the new Canadian federation left foreign affairs to the Imperial Parliament in Westminster, but the leaders of the federal parliament in Ottawa soon developed their own viewpoints on some issues, notably relations between the British Empire and the United States. Stable relations and secure trade with the United States were becoming increasingly vital to Canada, — so much so that historians have said that Canada's early diplomacy constituted a "North Atlantic triangle".

Most of Canada's early attempts at diplomacy necessarily involved the "mother country". Canada's first (informal) diplomatic officer was Sir John Rose, who was sent to London by Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. George Brown was subsequently dispatched to Washington by Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie to influence British-American trade talks. The British government desired to formalise Canada's representation abroad rather than deal with so many informal lobbyists, and so, in 1880, Alexander Tilloch Galt became the first High Commissioner sent from a Dominion to Britain.

When it came time to respond to imperial conflicts, Canada maintained a low profile, especially during the Sudan Campaign. When Britain sided with the US during the Alaska boundary dispute, it marked a low point in pro-British sentiment in Canada. By the time of the Boer War, however, Canadians volunteered to fight for the Empire in large numbers despite the lukewarm support of the government of Wilfrid Laurier, the first French-Catholic prime minister.

Economically, Canadian governments were interested in free trade with the United States; however, since this was difficult to negotiate and politically divisive, they became leading advocates of imperial preference, which met with limited enthusiasm in Britain.

First and Second World Wars

At the outbreak of World War I, the Canadian government and millions of Canadian volunteers enthusiastically joined Britain's side, but the sacrifices of the war, and the fact they were made in the name of the British Empire, caused domestic tension in Canada, and awakened a budding nationalism in Canadians. At the Paris Peace Conference, Canada demanded the right to sign treaties without British permission and to join the League of Nations. By the 1920s, Canada was taking a more independent stance on world affairs.

In 1926, through the Balfour Declaration, Britain declared that she would no longer legislate for the Dominions, and that they were now fully independent states with the right to conduct their own foreign affairs. This was later formalised by the Statute of Westminster 1931.

Loyalty to Britain still existed, however, and during the darkest days of the Second World War for Britain, after the fall of France and before the entry of the Soviet Union or the USA, Canada was Britain's principal ally in the North Atlantic, and a major source of weapons and food. However, the war showed that the Imperial alliance between Britain, Canada, and the other Dominions was no longer a dominant global power, not being able to prevent Hong Kong from being overrun by Japan, and narrowly avoiding a German invasion of Britain itself.

Owing to the destruction of much of Europe, Canada's relative economic and military importance was at a peak in the late 1940s, just as Britain's was declining. Both were dwarfed by the new superpowers, however, policymakers in both Britain and Canada were eager to participate in a lasting alliance with the United States for protection from the Soviet Union, which resulted in the creation of NATO in 1949. So while Britain and Canada were allies both before 1949 and after, before this it was part of a British-dominated Imperial alliance, whereas after it has always been a small part of a much broader Western Bloc where the United States is by far the most powerful member. This means that the strategic and political importance of military ties between the UK and Canada are much lower than British-American or Canadian-American ties. This is easily observed by Canada's participation in the NORAD scheme with the US for the common defence of North American airspace.

Constitutional independence

The definitive break in Canada's loyalist foreign policy came during the Suez Crisis of 1956 when the Canadian government flatly rejected calls from the British government for support of the latter's invasion of Egypt. Eventually, Canada helped the British (and their French and Israeli allies) to save face while extracting themselves from a public relations disaster. The Canadian delegation to the UN, led by future prime minister Lester B. Pearson, proposed a peacekeeping force to separate the two warring sides. For this he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Meanwhile, Canada's legal separation from Britain continued. Until 1946, Britain and Canada shared a common nationality code. The Canadian Citizenship Act 1946 gave Canadians a separate legal nationality from Britain. Canadians could no longer appeal court cases to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London after 1949.

The final constitutional ties between United Kingdom and Canada ended in 1982 with the passing of the Canada Act 1982. An Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that was passed at the request of the Canadian federal government to "patriate" Canada's constitution, ending the necessity for the country to request certain types of amendment to the Constitution of Canada to be made by the British parliament. The Act also formally ended the "request and consent" provisions of the Statute of Westminster 1931 in relation to Canada, whereby the British parliament had a general power to pass laws extending to Canada at its own request.

Formal economic relations between the two countries declined following Britain's accession to the European Economic Community in 1973. In both countries, regional economic ties loomed larger than the historical trans-Atlantic ones. In 1988, Canada signed a free trade agreement with the United States, which became the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 with the addition of Mexico. Thus, the two nations are now in separate trade blocs, the European Union and North American Free Trade Agreement respectively. Nevertheless, Britain remains the fifth largest overall foreign investor in Canada. In turn, Canada is the third largest foreign direct investor in Britain.

Trade and investment

.jpg)

Despite Canada's long-term shift towards proportionally more trade with the US, Canada–UK trade has continued to grow in absolute numbers. The UK is by far Canada’s most important commercial partner in Europe and, from a global perspective, ranks third after the United States and China. In 2010 total bilateral trade reached over C$27.1 billion, and over the last five years the UK has been Canada’s second- largest goods export market. The UK is an important source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Canada, ranking third after the United States and the Netherlands, and Canadian companies invest heavily in the UK. In 2010, the two-way stock of investment stood at almost CDN$115 billion.[1]

On 9 February 2011, the boards of the London Stock Exchange and the Toronto Stock Exchange agreed to a deal in which both holding companies for the stock exchanges would merge, creating a leading exchange group with the largest number of listed companies in the world, and a combined market capitalisation of £3.7 trillion (C$5.8 trillion). The merger was ultimately cancelled on 29 June 2011 when it became obvious TMX shareholders would not give the needed two-thirds approval.[2]

Canada and the UK – as members of the North American Free Trade Agreement and the European Union respectively – are working together on negotiations towards a Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada and the European Union. If approved, the agreement will begin to come into effect in 2016.[1]

In 2013, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of Canada resigned in order to take up a position as Governor of the Bank of England.

Tourism

In 2004, about 800,000 British residents visited Canada, making the United Kingdom, Canada's second-largest source of tourists after the United States. That same year, British visitors spent almost C$1 billion while visiting Canada. Britain was the third most-popular international destination for Canadian tourists in 2003, after the United States and Mexico – with some 700,000 visitors spending over C$800 million.[3]

Defence and security

The two countries have a long history of close collaboration in military affairs. Canada fought alongside Britain and its Allies in World War I. Canadians of British descent—the majority—gave widespread support arguing that Canadians had a duty to fight on behalf of their Motherland. Indeed, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, although French-Canadian, spoke for the majority of English-Canadians when he proclaimed: "It is our duty to let Great Britain know and to let the friends and foes of Great Britain know that there is in Canada but one mind and one heart and that all Canadians are behind the Mother Country."[4] It fought with Britain and its allies again in World War II.

Until 1972, the highest military decoration awarded to members of the British and Canadian Armed Forces, was the Victoria Cross. 81 members of the Canadian military (including those from Newfoundland) and 13 Canadians serving in British units had been awarded the Victoria Cross. In 1993, Canada created its own Victoria Cross.

In modern times they are members of the AUSCANNZUKUS military alliance including the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing alliance with the US, Australia and New Zealand. Both countries are members of NATO and participate in UN peacekeeping operations . Before 2011, the two countries' main areas of defense cooperation was in Afghanistan, where both were involved in the dangerous southern provinces. Both have provided air power to the NATO-led mission over Libya. Though still close allies militarily, it is no longer a given that Canada will follow Britain's lead in international conflicts.

Migration

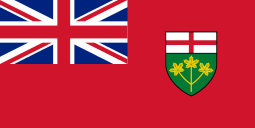

From the conquest of New France until 1966, Britain remained one of Canada's largest sources of immigrants, usually the largest. Since 1967, when Canadian laws were changed to remove preferences that had been given to Britons and other Europeans, British migration to Canada has continued at a lower level. When the constituent nations of the UK (England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland) are taken together, people of British ancestry still form Canada's largest ethnic group. In 2005, there were 579,620 UK-born people living in Canada, making up 1.9% of population of Canada.[5][6]

Historically, Canadians have travelled to Britain to advance their careers or studies to higher levels than could be done at home. Britain acted as the metropole, to which Canadians gravitated; this function has to a large extent been reduced as the Canadian economy and institutions have developed. The Office for National Statistics estimates that, in 2009, 82,000 Canadian-born people were living in the UK.[7] In 2012 this was the third largest community in the Canadian diaspora after Canadians in the United States, and Canadians in Hong Kong.

In recent years there has been growing support for the idea of freedom of movement between the UK, Canada and Australia, New Zealand with citizens able to live and work in any of the four countries - similar to the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement between Australia and New Zealand.[8][9]

Twinnings

-

Bala, Gwynedd and

Bala, Gwynedd and  Bala, Ontario

Bala, Ontario -

Blairgowrie and Rattray, Perth and Kinross and

Blairgowrie and Rattray, Perth and Kinross and  Fergus, Ontario

Fergus, Ontario -

Comrie, Perth and Kinross and

Comrie, Perth and Kinross and  Carleton Place, Ontario

Carleton Place, Ontario -

Coventry, West Midlands and

Coventry, West Midlands and  Cornwall, Ontario

Cornwall, Ontario -

Coventry, West Midlands and

Coventry, West Midlands and  Granby, Québec

Granby, Québec -

Coventry, West Midlands and

Coventry, West Midlands and  Windsor, Ontario

Windsor, Ontario -

Edinburgh, Lothian and

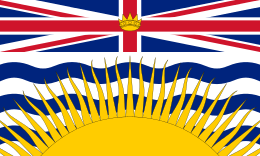

Edinburgh, Lothian and  Vancouver, British Columbia

Vancouver, British Columbia -

Halifax, West Yorkshire and

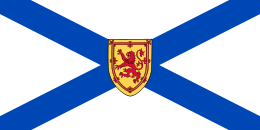

Halifax, West Yorkshire and  Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax, Nova Scotia -

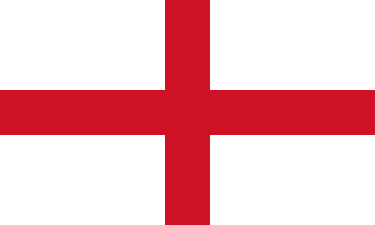

London, England and

London, England and  London, Ontario

London, Ontario -

Perth, Perth and Kinross and

Perth, Perth and Kinross and  Perth, Ontario

Perth, Ontario -

Stirling, Stirlingshire and

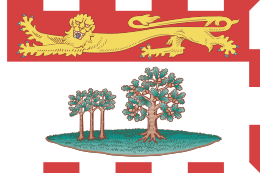

Stirling, Stirlingshire and  Summerside, Prince Edward Island

Summerside, Prince Edward Island -

Truro, Cornwall and

Truro, Cornwall and  Truro, Nova Scotia

Truro, Nova Scotia

Diplomacy

The contemporary political relationship between London and Ottawa is underpinned by a robust bilateral dialogue at head-of-government, ministerial and senior officials level. As Commonwealth realms, the two countries share a monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, and are both active members within the Commonwealth of Nations. In 2011, British Prime Minister David Cameron gave a joint address to the Canadian Parliament and in 2013, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper addressed both Houses of the British Parliament.[10][11]

Canada maintains a High Commission in London. The United Kingdom, in turn, maintains a High Commission in Ottawa, along with Consulates-General in Toronto, Montreal, Calgary, and Vancouver. In recent years Canada has sought closer Commonwealth cooperation, with the announcement in 2012 of joint diplomatic missions with the UK and of the intention of extending the scheme to include Australia and New Zealand, both of whom already share a head of state with Canada. In September 2012, Canada and the United Kingdom signed a Memorandum of Understanding on diplomatic cooperation, which promotes the co-location of embassies, the joint provision of consular services, and common crisis response.[12] The project has been criticised by some Canadian politicians as giving the appearance of a common foreign policy and is seen by many in the UK as an alternative and counterweight to EU integration.

Gallery

Canada House, home of the High Commission of Canada, London.

Canada House, home of the High Commission of Canada, London.- Earnscliffe, residence of the British High Commissioner to Canada.

.jpg) British Foreign Secretary William Hague with Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird, February 2014.

British Foreign Secretary William Hague with Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird, February 2014.

Quotes

- Canada's future first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, speaking in 1865, hoped that, if the Canadian colonies created a new federation, then Britain and Canada would have "a healthy and cordial alliance. Instead of looking upon us as a merely dependent colony, Britain will have in us a friendly nation, a subordinate, but still powerful people to stand by her in North America in peace or in war."[13]

- Speaking many years later at the beginning of the 1891 election (fought mostly over Canadian free trade with the United States), Macdonald said on February 3, 1891: "As for myself, my course is clear. A British subject I was born; a British subject I will die. With my utmost effort, with my latest breath, will I oppose the ‘veiled treason’ which attempts, by sordid means and mercenary proffers, to lure our people from their allegiance."[14]

See also

- High Commission of Canada in London

- High Commission of the United Kingdom in Ottawa

- List of High Commissioners from the United Kingdom to Canada

- List of Canadian High Commissioners to the United Kingdom

- Canada–European Union relations

- Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement

References

- 1 2 "Commercial and Economic Relations". Canadian High Commission. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ http://www.thestar.com/business/article/1016709--toronto-london-stock-exchange-merger-terminated

- ↑ http://www.international.gc.ca/canada-europa/united_kingdom/can_UK-en.asp Canadian High Commission in London

- ↑ Robert Borden (1969). Robert Laird Borden: His Memoirs. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-7735-6055-0.

- ↑ Place of birth for the immigrant population by period of immigration, 2006 counts and percentages

- ↑ Population by immigrant status and period of immigration, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories

- ↑ "Estimated population resident in the United Kingdom, by foreign country of birth (Table 1.3)". Office for National Statistics. September 2009. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ "Australians and New Zealanders should be free to live and work in UK, report says". theguardian.com. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Freedom of Movement Organisation". CFMO. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ "PM gives speech at Canadian Parliament". Gov.uk. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ "Canadian PM Stephen Harper visits UK Parliament". parliament.uk. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ "UK to share embassy premises with 'first cousins' Canada". theguardian.com. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada – Canada and the World: A History – 1867 – 1896: Forging a Nation

- ↑ Histor!ca "Election of 1891: A Question of Loyalty", James Marsh.

External links

- Government

- Visit Britain the British Tourist Board's Canadian site

- British High Commission The British High Commission in Ottawa

- Canadian High Commission Canadian High Commission in London