United Kingdom–United States relations

|

|

United Kingdom |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic Mission | |

| United Kingdom Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, London |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Kim Darroch | Ambassador Matthew Barzun |

British–American relations, also referred to as Anglo-American relations, encompass many complex relations ranging from two early wars to competition for world markets. Since 1940 they have been close military allies enjoying the Special Relationship built as wartime allies, and NATO partners.

The two nations are bound together by shared history, an overlap in religion and a common language and legal system, and kinship ties that reach back hundreds of years, including kindred, ancestral lines among English Americans, Scottish Americans, Welsh Americans, Scotch-Irish Americans and American Britons respectively. Today large numbers of expatriates live in both countries.

Through times of war and rebellion, peace and estrangement, as well as becoming friends and allies, Britain and the US cemented these deeply rooted links during World War II into what is known as the "Special Relationship", described in 2009 by British political commentator Christiane Amanpour as "the key trans-Atlantic alliance",[1] which the U.S. Senate Chair on European Affairs acknowledged in 2010 as "one of the cornerstones of stability around the world."[2] In broader historic perspective, the Special Relationship has been called the "cornerstone of the modern, democratic world order".[3]

Today, the United Kingdom affirms its relationship with the United States as its "most important bilateral partnership" in the current British foreign policy,[4] and the American foreign policy also affirms its relationship with Britain as its most important relationship,[5][6] as evidenced in aligned political affairs, mutual cooperation in the areas of trade, commerce, finance, technology, academics, as well as the arts and sciences; the sharing of government and military intelligence, and joint combat operations and peacekeeping missions carried out between the United States Armed Forces and the British Armed Forces. Canada has historically been the largest importer of U.S. goods and the principal exporter of goods to the USA. As of January 2015 the UK was fifth in terms of exports and seventh in terms of import of goods.[7]

The two countries combined make up a huge percentage of world trade, a significant impact of the cultures of many other countries and territories, and are the largest economies and the most populous nodes of the Anglosphere, with a combined population of around 385 million in 2015. Together, they have given the English language a dominant role in many sectors of the modern world. In addition to the Special Relationship between the two countries, most British people perceive the U.S. positively, with the U.S. coming in the top three of polls consistently;[8][9] according to a 2015 Gallup poll, 90% of Americans view Great Britain favorably.[10]

Country comparison

| |

| |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 64,511,000 | 321,034,355 |

| Area | 243,610 km2 (94,060 sq mi) | 9,629,091 km2 (3,717,813 sq mi) |

| Population density | 255.6/km2 (98.7/sq mi) | 34.2/km2 (13.2/sq mi) |

| Capital city | London | Washington, D.C. |

| Largest city | London – 8,630,000 (14,614,409 Metro) | New York City – 8,491,079 (20,092,883 Metro) |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | Federal presidential constitutional republic |

| First leader | George III | George Washington |

| Current leader | Theresa May (Prime Minister)

Queen Elizabeth II (Constitutional Monarch) |

Barack Obama (President)

Donald Trump (President-elect) |

| Main language | English | English |

| Main religions | 60% Christian 30% Non-Religious 10% Other |

74% Christian 20% Non-Religious 6% Other |

| Ethnic groups | 87.1% White British 7.0% British Asian 3.0% Black British 2.0% Multiracial 0.9% Other |

77.7% White American 16.4% Hispanic 13.2% African American 5.3% Asian American 2.4% Multiracial 1.2% American Indian or Alaska Native 0.2% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander 0.2% Native Puerto Rican or Caribbean Islander |

| GDP (nominal) | US$3.001 trillion | $17.528 trillion |

| GDP (nominal) per capita | US$43,830 | $54,980 |

| GDP (PPP) | $2.897 trillion | $17.528 trillion |

| GDP (PPP) per capita | US$37,711 | $54,980 |

| Real GDP growth rate | 2.5% | 1.9% |

| Military expenditure | $72.9 billion | $640.0 billion |

| Military personnel | 300,000 | 2,927,754 |

| English speakers | 60,895,000 | 294,469,560 |

| Labor force | 30,643,000 | 156,080,000 |

| Mobile phones | 75,750,000 | 327,577,529 |

Special Relationship

The Special Relationship characterizes the exceptionally close political, diplomatic, cultural, economic, military and historical relations between the two countries. It is specially used for relations since 1940.

History

Origins

After several failed attempts, the first permanent English settlement in mainland North America was established in 1607 at Jamestown in the Colony and Dominion of Virginia. By 1624, the Colony and Dominion of Virginia ceased to be a charter colony administered by the Virginia Company of London and became a crown colony. The Pilgrims were a small Protestant sect based in England and Amsterdam; they sent a group of settlers on the Mayflower. After drawing up the Mayflower Compact by which they gave themselves broad powers of self-governance, they established the small Plymouth Colony in 1620. In 1630 the Puritans established the much larger Massachusetts Bay Colony; they sought to reform the Church of England by creating a new and "more pure" church in the New World.

Other colonies followed in Province of Maine (1622), Province of Maryland (1632), Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (1636) and Connecticut Colony (1636). Later came the founding of Province of Carolina (1663) (divided in 1729 into the Province of North Carolina and the Province of South Carolina). The Province of New Hampshire was founded in 1691. Next came the Province of Georgia in 1732.

The Province of New York was formed from the conquered Dutch colony of New Netherland. In 1674, the Province of New Jersey was split off from New York. In 1681 William Penn was awarded a royal charter in 1681 by King Charles II to found Province of Pennsylvania.

The colonies each reported separately to London. There was a failed effort to group the colonies into the Dominion of New England, 1686-89.

Migration

During the 17th century, an estimated 350,000 English and Welsh migrants arrived as permanent residents in the Thirteen Colonies. In the century after the Acts of Union 1707 this was surpassed in rate and number by Scottish and Irish migrants.[11]

During British settler colonization, liberal administrative, juridical, and market institutions were introduced, positively associated with socioeconomic development.[12] At the same time, colonial policy was also quasi-mercantilist, encouraging trade within the Empire, discouraging trade with other powers, and discouraging the rise of manufacturing in the colonies, which had been established to increase the trade and wealth of the mother country. Britain made much greater profits from the sugar trade of its commercial colonies in the Caribbean.

The introduction of coercive labor institutions was another feature of the colonial period.[12] All of the Thirteen Colonies were involved in the slave trade. Slaves in the Middle Colonies and New England Colonies typically worked as house servants, artisans, laborers and craftsmen. Early on, slaves in the Southern Colonies worked primarily in agriculture, on farms and plantations growing indigo, rice, cotton, and tobacco for export.

The French and Indian War, fought between 1754 and 1763, was the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War. The conflict, the fourth such colonial war between France and Britain in North America, resulted in the British acquisition of New France, with its French Catholic population. Under the Treaty of Paris signed in 1763, the French ceded control of French Louisiana east of the Mississippi River to the British, which became known as the Indian Reserve.

Religion

The religious ties between the metropole and the colonies were pronounced. Most of the churches were transplants from England (or Germany). The Puritans of New England seldom kept in touch with nonconformists in England. Much closer were the transatlantic relationships maintained by the Quakers, especially in Pennsylvania. The Methodists also maintained close ties.[13][14]

The Anglican Church was officially established in the Southern colonies, which meant that local taxes paid the salary of the minister, the parish had civic responsibilities such as poor relief, and the local gentry controlled the parish. The church was disestablished during the American Revolution. The Anglican churches in America were under the authority of the Bishop of London, and there was a long debate over whether to establish an Anglican bishop in America. The other Protestants blocked any such appointment. After the Revolution the newly formed Episcopal Church selected its own bishop and kept its distance from London.[15]

Proportions of English ancestry

Proportions of English ancestry Proportions of Scots ancestry

Proportions of Scots ancestry Proportions of Scots-Irish ancestry

Proportions of Scots-Irish ancestry Proportions of Welsh ancestry

Proportions of Welsh ancestry

American Revolution

The Thirteen Colonies gradually obtained more, albeit limited, self-government.[16] British mercantilist policies became more stringent, benefiting the mother country which resulted in trade restrictions, thereby limiting the growth of the colonial economy and artificially constraining colonial merchants' earning potential. The American Colonies were expected to help repay debt that had accrued during the French and Indian War. Tensions escalated from 1765 to 1775 over issues of taxation without representation and control by King George III. Stemming from the Boston Massacre of 1770 when British Redcoats opened fire on civilians, rebellion consumed the outraged colonists. The British Parliament had imposed a series of taxes such as the Stamp Act of 1765, and later the Tea Act of 1773, against which an angry mob of colonists protested in the Boston Tea Party by dumping chests of tea into Boston Harbor. The British Parliament responded to the defiance of the colonists by passing what the colonials called the Intolerable Acts in 1774. This course of events ultimately triggered the first shots fired in the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775 and the beginning of the American War of Independence. A British victory at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775 agitated tensions even further. While the goal of attaining independence was sought by a majority known as Patriots, a minority known as Loyalists wished to remain as British subjects indefinitely. When the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in May 1775, deliberations conducted by notable figures such as Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and John Adams eventually resulted in seeking full independence from the mother country. Thus, the Declaration of Independence, unanimously ratified on July 4, 1776, was a radical and decisive break. The United States of America became the first colony in the world to successfully achieve independence in the modern era.

In early 1775 the Patriots forced all the British officials and soldiers out of the new nation. The British returned in force in August 1776, and captured New York City, which became their base until the war ended in 1783. The British, using their powerful navy, could capture major ports, but 90% of the Americans lived in rural areas where they had full control. After the Patriots captured a British invasion force moving down from Canada in the Saratoga campaign of 1777, France entered the war as an ally of the US, and added the Netherlands and Spain as French allies. Britain lost naval superiority and had no major allies and few friends in Europe. The British strategy was then refocused on the South, where they expected large numbers of Loyalists would fight alongside the redcoats. Far fewer Loyalists took up arms than Britain needed; royal efforts to control the countryside in the South failed. When the British army tried to return to New York, its rescue fleet was turned back by the French fleet and its army was captured by combined French-American forces under General George Washington at the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781. That effectively ended the fighting.

Peace treaty

The Treaty of Paris ended the war in 1783 on terms quite favorable to the new nation.[17]

The key events were in September 1782, when the French Foreign Minister Vergennes proposed a solution that was strongly opposed by his ally the United States. France was exhausted by the war, and everyone wanted peace except Spain, which insisted on continuing the war until it captured Gibraltar from the British. Vergennes came up with a deal that Spain would accept instead of Gibraltar. The United States would gain its independence but be confined to the area east of the Appalachian Mountains. Britain would take the area north of the Ohio River. In the area south of that would be set up an independent Indian state under Spanish control. It would be an Indian barrier state. The Americans realized that French friendship was worthless during these negotiations: they could get a better deal directly from London. John Jay promptly told the British that he was willing to negotiate directly with them, cutting off France and Spain. The British Prime Minister Lord Shelburne agreed. He was in full charge of the British negotiations and he now saw a chance to split the United States away from France and make the new country a valuable economic partner.[18] The western terms were that the United States would gain all of the area east of the Mississippi River, north of Florida, and south of Canada. The northern boundary would be almost the same as today.[19] The United States would gain fishing rights off Canadian coasts, and agreed to allow British merchants and Loyalists to try to recover their property. It was a highly favorable treaty for the United States, and deliberately so from the British point of view. Shelburne foresaw a highly profitable two-way trade between Britain and the rapidly growing United States, which indeed came to pass.[20]

End of the Revolution

The treaty was finally ratified in 1784. The British evacuated their soldiers and civilians in New York, Charleston and Savannah in late 1783. Over 80 percent of the half-million Loyalists remained in the United States and became American citizens. The others mostly went to Canada, and referred to themselves as the United Empire Loyalists. Merchants and men of affairs often went to Britain to reestablish their business connections.[21][22] Rich southern Loyalists, taking their slaves with them, typically headed to plantations in the West Indies. The British also took away about 3000 free blacks, former slaves who fought the British army; they went to Nova Scotia. Many found it inhospitable and went to Sierra Leone, the British colony in Africa.[23]

The new nation gained control of nearly all the land east of the Mississippi and south of the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. The British colonies of East and West Florida were given to Spain as its reward. The Native American tribes allied with Britain struggled in the aftermath; the British ignored them at the Peace conference, and most came under American control unless they moved to Canada or to Spanish territory. The British kept forts in the American Midwest (especially in Michigan and Wisconsin), where they supplied weapons to Indian tribes.[24]

1783–1807: Role of Jay Treaty

Trade resumed between the two nations when the war ended. The British allowed all exports to America but forbade some American food exports to its colonies in the West Indies. British exports reached £3.7 million, compared to imports of only £750,000. The imbalance caused a shortage of gold in the US.

In 1785, John Adams became the first American plenipotentiary minister, now known as an ambassador, to the Court of St James's. King George III received him graciously. In 1791, Great Britain sent its first diplomatic envoy, George Hammond, to the United States.

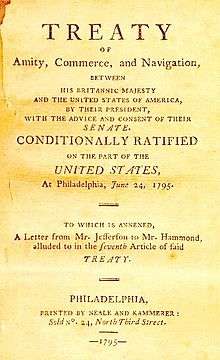

When Great Britain and France went to war in 1793, relations between the United States and Great Britain also verged on war. Tensions were subdued when the Jay Treaty was signed in 1794, which established a decade of peace and prosperous trade relations.[25] The historian Marshall Smelser argues that the treaty effectively postponed war with Britain, or at least postponed it until the United States was strong enough to handle it.[26]

Bradford Perkins argued that the treaty was the first to establish a special relationship between Britain and the United States, with a second installment under Lord Salisbury. In his view, the treaty worked for ten years to secure peace between Britain and America: "The decade may be characterized as the period of "The First Rapprochement." As Perkins concludes,

"For about ten years there was peace on the frontier, joint recognition of the value of commercial intercourse, and even, by comparison with both preceding and succeeding epochs, a muting of strife over ship seizures and impressment. Two controversies with France… pushed the English-speaking powers even more closely together."[27]

Starting at swords' point in 1794, the Jay treaty reversed the tensions, Perkins concludes: "Through a decade of world war and peace, successive governments on both sides of the Atlantic were able to bring about and preserve a cordiality which often approached genuine friendship."[28]

Historian Joseph Ellis finds the terms of the treaty "one-sided in Britain's favor", but asserts a consensus of historians agrees that it was

"a shrewd bargain for the United States. It bet, in effect, on England rather than France as the hegemonic European power of the future, which proved prophetic. It recognized the massive dependence of the American economy on trade with England. In a sense it was a precocious preview of the Monroe Doctrine (1823), for it linked American security and economic development to the British fleet, which provided a protective shield of incalculable value throughout the nineteenth century. Mostly, it postponed war with England until America was economically and politically more capable of fighting one."[29]

The US proclaimed its neutrality in the wars between Britain and France (1793–1815), and profited greatly by selling food, timber and other supplies to both sides.

Thomas Jefferson had bitterly opposed the Jay Treaty because he feared it would strengthen anti-republican political enemies. When Jefferson became president in 1801, he did not repudiate the treaty. He kept the Federalist minister, Rufus King in London to negotiate a successful resolution to outstanding issues regarding cash payments and boundaries. The amity broke down in 1805, as relations turned increasingly hostile as a prelude to the War of 1812. Jefferson rejected a renewal of the Jay Treaty in the Monroe–Pinkney Treaty of 1806 as negotiated by his diplomats and agreed to by London; he never sent it to the Senate.

The legal international slave trade was largely suppressed after Great Britain passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in 1807. At the urging of President Jefferson, the United States passed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves in 1807, to take effect 1 January, 1808.

War of 1812

The United States imposed a trade embargo, namely the Embargo Act of 1807, in retaliation for Britain's blockade of France, which involved the visit and search of neutral merchantmen, and resulted in the suppression of Franco-United States trade for the duration of the Napoleonic Wars.[30] The Royal Navy also boarded American ships and impressed sailors suspected of being British deserters.[31] Western expansion into the American Midwest (Ohio to Wisconsin) was hindered by Indian tribes given munitions and support by British agents. Indeed, Britain's goal was the creation of an independent Indian state to block American expansion.[32]

After diplomacy and the boycott had failed, the issue of national honour and independence came to the fore.[33] Brands says, "The other war hawks spoke of the struggle with Britain as a second war of independence; [Andrew] Jackson, who still bore scars from the first war of independence held that view with special conviction. The approaching conflict was about violations of American rights, but it was also vindication of American identity."[34]

Finally in June 1812 President James Madison called for war, and overcame the opposition of Northeastern business interests. The American strategy called for a war against British shipping and especially cutting off food shipments to the British sugar plantations in the West Indies. Conquest of Canada was a tactic designed to give the Americans a strong bargaining position.[35] The main British goal was to defeat France, so until that happened in 1814 the war was primarily defensive. To enlist allies among the Indians, led by Tecumseh, the British promised an independent Indian state would be created in American territory. Repeated American invasions of Canada were fiascoes, because of inadequate preparations, very poor generals, and the refusal of militia units to leave their home grounds. The Americans took control of Lake Erie in 1813 and destroyed the power of the Indian allies of the British in the Northwest and Southeast. The British invasion of the Chesapeake Bay in 1814 culminated in the "Burning of Washington", but the subsequent British attack on Baltimore was repelled. The British invasion of New York state in 1814 was defeated at the Battle of Plattsburgh, and the invasion of Louisiana that launched before word of a ceasefire had reached General Andrew Jackson was decisively defeated at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. Negotiations began in 1814 and produced the Treaty of Ghent, which restored the status quo ante bellum. No territorial gains were made by either side, and the British plan to create an Indian nation was abandoned. The United Kingdom retained the theoretical right of impressment, but stopped impressing any sailors, while the United States dropped the issue for good.[36] The US celebrated the outcome as a victorious "second war of independence." The British, having finally defeated Napoleon at Waterloo, celebrated that triumph and largely forgot the war with America. Tensions between the US and Canada were resolved through diplomacy. The War of 1812 marked the end of a long period of conflict (1775–1815) and ushered in a new era of peace between the two nations.

Disputes 1815–60

The Monroe Doctrine, a unilateral response in 1823 to a British suggestion of a joint declaration, expressed American hostility to further European encroachment in the Western hemisphere. Nevertheless, the United States benefited from the common outlook in British policy and its enforcement by the Royal Navy. In the 1840s several states defaulted on bonds owned by British investors. London bankers avoided state bonds afterwards, but invested heavily in American railroad bonds.[37]

In several episodes the American general Winfield Scott proved a sagacious diplomat by tamping down emotions and reaching acceptable compromises.[38] Scott handled the Caroline affair in 1837. Rebels from British North America (now Ontario) fled to New York and used a small American ship called the Caroline to smuggle supplies into Canada after their rebellion was suppressed. In late 1837, Canadian militia crossed the border into the US and burned the ship, leading to diplomatic protests, a flare-up of Anglophobia, and other incidents.

stretched from 42N to 54 40'N. The most heavily disputed portion is highlighted

Tensions on the vague Maine–New Brunswick boundary involved rival teams of lumberjacks in the bloodless Aroostook War of 1839. There was no shooting but both sides tried to uphold national honor and gain a few more miles of timber land. Each side had an old secret map that apparently showed the other side had the better legal case, so compromise was easily reached in the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842, which settled the border in Maine and Minnesota.[39][40] In 1859, the bloodless Pig War determined the position of the border in relation to the San Juan Islands and Gulf Islands. But the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty proved an important step in improving relations.

Relations with the United States were often strained, and even verged on war when Britain almost supported the Confederacy in the early part of the American Civil War. British leaders were constantly annoyed from the 1840s to the 1860s by what they saw as Washington's pandering to the democratic mob, as in the Oregon boundary dispute in 1844-46. However British middle-class public opinion sensed a "special relationship" between the two peoples based on language, migration, evangelical Protestantism, liberal traditions, and extensive trade. This constituency rejected war, forcing London to appease the Americans. During the Trent affair of late 1861, London drew the line and Washington retreated.[41]

In 1844-48 the two nations had overlapping claims to Oregon. The area was largely unsettled, making it easy to end the crisis in 1848 by a compromise that split the region evenly, with British Columbia to Great Britain, and Washington, Idaho, and Oregon to America. The US then turned its attention to Mexico, which threatened war over the annexation of Texas. Britain tried without success to moderate the Mexicans, but when the war began it remained neutral. The US gained California, in which the British had shown only passing interest.[42]

American Civil War

In the American Civil War a major Confederate goal was to win recognition from Britain and France, which it expected would lead them to war with the US and enable the Confederacy to win independence. Because of the astute American diplomacy, no nation ever recognized the Confederacy and war with Britain was averted. Nevertheless, there was considerable British sentiment in favor of weakening the US by helping the South win.[43] At the beginning of the war Britain issued a proclamation of neutrality. The Confederate States of America had assumed all along that Britain would surely enter the war to protect its vital supply of cotton. This "King Cotton" argument was one reason the Confederates felt confident in the first place about going to war, but the Southerners had never consulted the Europeans and were tardy in sending diplomats. Even before the fighting began in April 1861 Confederate citizens (acting without government authority) cut off cotton shipments in an effort to exert cotton diplomacy. It failed because Britain had warehouses filled with cotton, whose value was soaring; not until 1862 did shortages become acute.[44]

The Trent Affair in late 1861 nearly caused a war. A warship of the U.S. Navy stopped the British civilian vessel RMS Trent and took off two Confederate diplomats, James Murray Mason and John Slidell. Britain prepared for war and demanded their immediate release. President Lincoln released the diplomats and the episode ended quietly.[45]

Britain realized that any recognition of an independent Confederacy would be treated as an act of war against the United States. The British economy was heavily reliant on trade with the United States, most notably cheap grain imports which in the event of war, would be cut off by the Americans. Indeed, the Americans would launch all-out naval war against the entire British merchant fleet.

Despite outrage and intense American protests, London allowed the British-built CSS Alabama to leave port and become a commerce raider under the naval flag of the Confederacy. The war ended in 1865; arbitration settled the issue in 1871, with a payment of $15.5 million in gold for the damages caused.[46]

In January 1863 Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which was strongly supported by liberal elements in Britain. The British government predicted that emancipation of the slaves would create a race war, and that intervention might be required on humanitarian grounds. There was no race war, and the declining capabilities of the Confederacy—such as loss of major ports and rivers—made its likelihood of success smaller and smaller.[47]

Late 19th century

Relations were chilly during the 1860s as Americans resented British and Canadian roles during the Civil War. After the war American authorities looked the other way as Irish "Fenians" plotted and even attempted an invasion of Canada.[48] The Fenians proved a failure but Irish American politicians, a growing power in the Democratic Party demanded more independence for Ireland and made anti-British rhetoric—called "twisting the lion's tail"—a staple of election campaign appeals to the Irish vote.[49]

Britain persisted in its free trade policy even as its major rivals, the US and Germany, turned to high tariffs (as did Canada). American heavy industry grew faster than Britain, and by the 1890s was crowding British machinery and other products out of the world market.[50] London, however, remained the world's financial center, even as much of its investment was directed toward American railways. The Americans remained far behind the British in international shipping and insurance.[51]

The American "invasion" of the British home market demanded a response.[52] Tariffs, although increasingly under consideration, were not imposed until the 1930s. Therefore, British businessmen were obliged to lose their market or else rethink and modernize their operations. The boot and shoe industry faced increasing imports of American footwear; Americans took over the market for shoe machinery. British companies realized they had to meet the competition so they re-examined their traditional methods of work, labor utilization, and industrial relations, and to rethink how to market footwear in terms of the demand for fashion.[53]

Venezuelan and Alaska border disputes

In 1895 the Venezuela Crisis with the United States erupted. A border dispute between a British colony and Venezuela caused a major Anglo-American crisis when the United States intervened to take Venezuela's side. Propaganda sponsored by Venezuela convinced American public opinion that the British were infringing on Venezuelan territory. The United States demanded an explanation and Prime Minister Salisbury refused. The crisis escalated when President Grover Cleveland, citing the Monroe Doctrine, issued an ultimatum in late 1895. Salisbury's cabinet convinced him he had to go to arbitration. Both sides calmed down and the issue was quickly resolved through arbitration which largely upheld the British position on the legal boundary line. Salisbury remained angry but a consensus was reached in London, led by Lord Landsdowne, to seek much friendlier relations with the United States.[54][55] By standing with a Latin American nation against the encroachment of the British, the US improved relations with the Latin Americans, and the cordial manner of the procedure improved diplomatic relations with Britain.[56]

The Olney-Pauncefote Treaty of 1897 was a proposed treaty between the United States and Britain in 1897 that required arbitration of major disputes. Despite wide public and elite support, the treaty was rejected by the U.S. Senate, which was jealous of its prerogatives, and never went into effect.[57]

Arbitration was used to settle the dispute over the boundary between Alaska and Canada, but the Canadians felt betrayed by the result. The Alaska Purchase of 1867 drew the boundary between Canada and Alaska in ambiguous fashion. With the gold rush into the Yukon in 1898, miners had to enter through Alaska and Canada wanted the boundary redrawn to obtain its own seaport. Canada rejected the American offer of a long-term lease on an American port. The issue went to arbitration and the Alaska boundary dispute was finally resolved by an arbitration in 1903. The decision favoured the US when the British judge sided with the three American judges against the two Canadian judges on the arbitration panel. Canadian public opinion was outraged that their interests were sacrificed by London for the benefit of British-American harmony.[58]

The Great Rapprochement

The Great Rapprochement is a term used to describe the convergence of social and political objectives between the United Kingdom and the United States from 1895 until World War I began in 1914. The large Irish Catholic element in the US provided a major base for demands for Irish independence, and occasioned anti-British rhetoric, especially at election time.[59]

The most notable sign of improving relations during the Great Rapprochement was Britain's actions during the Spanish–American War (started 1898). Initially Britain supported the Spanish Empire and its colonial rule over Cuba, since the perceived threat of American occupation and a territorial acquisition of Cuba by the United States might harm British trade and commercial interests within its own imperial possessions in the West Indies. However, after the United States made genuine assurances that it would grant Cuba's independence (which eventually occurred in 1902 under the terms dictated in the Platt Amendment), the British abandoned this policy and ultimately sided with the United States, unlike most other European powers who supported Spain. In return the US government supported Britain during the Boer War, although many Americans favored the Boers.[60]

Victory in the Spanish–American War had given the United States its own rising empire. This new status was demonstrated in 1900–01, when the US and Britain, as part of the Eight-Nation Alliance, suppressed the Boxer Rebellion and maintained foreign Concessions (colonies) in Qing Dynasty China.

In 1907–09, President Theodore Roosevelt sent the "Great White Fleet" on an international tour, to demonstrate the power projection of the United States' blue-water navy, which had become second only to the Royal Navy in size and firepower.[61][62]

World War I

The United States had a policy of strict neutrality. The United States was willing to export any product to any country. Germany could not import anything due to the British blockade, so the American trade was with the Allies. It was financed by the sale of American bonds and stocks owned by the British. When that was exhausted the British borrowed heavily from New York banks. When that credit ran dry in late 1916, a financial crisis was at hand for Britain.[63]

American public opinion moved steadily against Germany, especially in the wake of the Belgian atrocities in 1914 and the sinking of the RMS Lusitania in 1915. The large German American and Irish Catholic element called for staying out of the war, but the German Americans were increasingly marginalized. The Germans renewed unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917 knowing it would lead to war with the US. Germany's invitation to Mexico to join together in war against the US in the Zimmermann Telegram was the last straw, and the US declared war in April 1917. The Americans planned to send money, food and munitions, but it soon became clear that millions of soldiers would be needed to decide the war on the Western Front.[64]

The US sent two million soldiers to Europe under the command of General John J. Pershing, with more on the way as the war ended.[65] Many of the Allied forces were skeptical of the competence of the American Expeditionary Force, which in 1917 was severely lacking in training and experience. By summer 1918, the American doughboys were arriving at 10,000 a day, as the German forces were shrinking because they had run out of manpower.

Although Woodrow Wilson had wanted to wage war for the sake of humanity, the negotiations over the Treaty of Versailles underlined in his Fourteen Points for Peace made it plainly clear that his diplomatic position had weakened with victory. The borders of Europe were redrawn on the basis of national self-determination, with the exception of Germany under the newly formed Weimar Republic. Financial reparations were imposed on the Germans, despite British reservations and American protests, largely because of France's desire for punitive peace[66] and, in what many at the time deemed revenge, for previous conflicts with Germany in the 19th century.

Inter-war years

By 1921 a cardinal principle of British foreign-policy was to "cultivate the closest relations with the United States." As a result, Britain decided not to renew its military alliance with Japan, which was becoming a major rival to the United States in the Pacific.[67]

The US sponsored a successful Washington Naval Conference in 1922 that largely ended the naval arms race for a decade. World War I marked the end of the Royal Navy's superiority, an eclipse acknowledged in the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, when the United States and Britain agreed to equal tonnage quotas on warships. By 1932, the 1922 treaty was not renewed and Britain, Japan and the US were again in a naval race.[68]

In the 1920s, bilateral relations were generally friendly. In 1923 London renegotiated its ₤978 million war debt to the U.S. Treasury by promising regular payments of ₤34 million for ten years then ₤40 million for 52 years. The idea was for the US to loan money to Germany, which in turn paid reparations to Britain, which in turn paid off its loans from the US government. In 1931 all German payments ended, and in 1932 Britain suspended its payments to the US. The debt was finally repaid after 1945.[69]

The US refused to join the League of Nations, but its absence made little difference to British policy. While the United States participated in functional bodies of the League —to the satisfaction of Britain— it was a delicate issue linking the US to the League in public. Thus, major conferences, especially the Washington Conference of 1922 occurred outside League auspices. The US refused to send official delegates to League committees, instead sending unofficial "observers."

During the Great Depression, the United States was preoccupied with its own internal affairs and economic recovery, espousing an isolationist policy. When the US raised tariffs in 1930, the British retaliated by raising their tariffs against outside countries (such as the US) while giving special trade preferences inside the Commonwealth. The US demanded these special trade preferences be ended in 1946 in exchange for a large loan.[70]

The overall world total of all trade plunged by over two-thirds, while trade between the US and Britain shrank from $848 million in 1929 to $288 million in 1932, a decline of almost two-thirds (66%).[71]

When Britain in 1933 called a worldwide London Economic Conference to help resolve the depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt killed it by refusing to cooperate.[72]

Tensions over the Irish question faded with the independence of the Irish Free State in 1922. The American Irish had achieved their goal, and in 1938 its leader Joseph P. Kennedy became ambassador to the Court of St. James's. He moved in high London society and his daughter married into the aristocracy. Kennedy supported the Neville Chamberlain policy of appeasement toward Germany, and when the war began he advised Washington that prospects for Britain's survival were bleak. When Winston Churchill came to power in 1940, Kennedy lost all his influence in London and Washington.[73][74]

World War II

Although many of the American people were sympathetic to Britain during the war with Nazi Germany, there was widespread opposition to American intervention in European affairs. This was reflected in a series of Neutrality Acts ratified by the United States Congress in 1935, 1936, and 1937. However, President Roosevelt's policy of cash-and-carry still allowed Britain and France to order munitions from the United States and carry them home.

Churchill, who had long warned against Germany and demanded rearmament, became prime minister after Chamberlain's policy of appeasement had totally collapsed and Britain was unable to reverse the German invasion of Norway in April 1940. After the fall of France in June 1940, Roosevelt gave Britain and (after June 1941) the Soviet Union all aid short of war. The Destroyers for Bases Agreement which was signed in September 1940, gave the United States a 99-year rent-free lease of numerous land and air bases throughout the British Empire in exchange for the Royal Navy receiving 50 old destroyers from the United States Navy. Beginning in March 1941, the United States enacted Lend-Lease in the form of tanks, fighter airplanes, munitions, bullets, food, and medical supplies. Britain received $31.4 billion out of a total of $50.1 billion sent to the Allies.[75][76]

In December 1941 at the important Arcadia Conference in Washington, top British and American leaders agreed on strategy. They set up the Combined Chiefs of Staff to plot and coordinate strategy and operations. Military cooperation was close and successful.[77]

Technical collaboration was even closer, as the two nations shared secrets and weapons regarding the proximity fuze (fuse) and radar, as well as airplane engines, Nazi codes, and the atomic bomb.[78][79][80]

Millions of American servicemen were based in Britain during the war. Americans were paid five times more than comparable British servicemen, which led to a certain amount of friction with British men and intermarriage with British women.[81]

In 1945 Britain sent a portion of the British fleet to assist the planned October invasion of Japan by the USA, but this was cancelled when Japan was forced to surrender unconditionally in August.

India

Serious tension erupted over American demands that India be given independence, a proposition Churchill vehemently rejected. For years Roosevelt had encouraged Britain's disengagement from India. The American position was based on principled opposition to colonialism, practical concern for the outcome of the war, and the expectation of a large American role in a post-colonial era. In 1942 when the Congress Party launched a Quit India movement, the British authorities immediately arrested tens of thousands of activists (including Gandhi). Meanwhile, India became the main American staging base for aid to China. Churchill threatened to resign if Roosevelt pushed too hard, so Roosevelt backed down.[82][83]

Cold War

In the aftermath of the war Britain faced a financial crisis, whereas the United States was in the midst of an economic boom. The process of de-colonization accelerated with the independence Britain granted to India, Pakistan and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1947. The Labour government, which was alarmed at the threat of Communism in the Balkans, implored the US to take over the British role in Greece, which led to the Truman Doctrine in 1947, with financial and military aid to Greece and Turkey as Britain withdrew from the region.[84]

The US provided financial aid in the form of the Anglo-American loan of 1946, a 50-year loan with a low 2% interest rate starting in 1950. A more permanent solution was the Marshall Plan of 1948–51, which poured $13 billion into western Europe, of which $3.3 billion went to Britain to help modernize its infrastructure and business practices. The aid was a gift and carried requirements that Britain balance its budget, control tariffs and maintain adequate currency reserves.[85]

The need to form a united front against the Soviet threat compelled the US and Britain to cooperate in helping to form the North Atlantic Treaty Organization with their European allies. NATO is a mutual defense alliance whereby an attack on one member country is deemed an attack on all members.

The United States had an anti-colonial and anti-communist stance in its foreign policy throughout the Cold War. Military forces from the United States and the United Kingdom were heavily involved in the Korean War, fighting under a United Nations mandate. Military forces withdrew when a stalemate was implemented in 1953. When the Suez Crisis erupted in October 1956, the United States feared a wider war, after the Soviet Union threatened to intervene on the Egyptian side. Thus the United States applied sustained econo-financial pressure to encourage and ultimately force the United Kingdom, Israel and France to end their invasion of Egypt. British post-war debt was so large that economic sanctions could have caused a devaluation of sterling. This was something the UK government intended to avoid at all costs, and when it became clear that the international sanctions were serious, the British and their French allies withdrew their forces back to pre-war positions. The following year saw the resignation of Sir Anthony Eden.

Dwight D. Eisenhower's victory in the American presidential election in 1952 might have been expected to guarantee a continuance of good United States-United Kingdom relations, if not a period of even closer collaboration. Anglo-American cooperation during Eisenhower's presidency was troubled, approaching in 1956 a complete breakdown that represented the lowest point in the relations between the two countries since the 1920s.

Through the US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement signed in 1958, the United States assisted the United Kingdom in their own development of a nuclear arsenal. In April 1963, John F. Kennedy and Harold Macmillan signed the Polaris Sales Agreement to the effect of the United States agreeing to supply the UGM-27 Polaris ballistic missile to the United Kingdom for use in the Royal Navy's submarine fleet starting in 1968.[86]

The United States gradually became involved in the Vietnam War in the early 1960s, but this time received no support from the United Kingdom. Anti-Americanism due to the Vietnam War and a lack of American support for France and the United Kingdom over the Suez Crisis weighed heavily on the minds of many in Europe. Harold Wilson refused to send British troops to Indochina.

Edward Heath and Richard Nixon maintained a close relationship throughout their terms in office.[87] Heath deviated from his predecessors by supporting Nixon's decision to bomb Hanoi and Haiphong in Vietnam in April 1972.[88] Despite this personal affection, Anglo-American relations deteriorated noticeably during the early 1970s. Throughout his premiership, Heath insisted on using the phrase "natural relationship" instead of "special relationship" to refer to Anglo-American relations, acknowledging the historical and cultural similarities but carefully denying anything special beyond that.[89] Heath was determined to restore a measure of equality to Anglo-American relations which the USA had increasingly dominated as the power and economy of the United Kingdom flagged in the post-colonial era.[90]

Heath's renewed push for British admittance to the European Economic Community (EEC) brought new tensions between the United Kingdom and the United States. French President Charles De Gaulle, who believed that British entry would allow undue American influence on the organization, had vetoed previous British attempts at entry. Heath's final bid benefited from the more moderate views of Georges Pompidou, De Gaulle's successor as President of France, and his own Eurocentric foreign policy schedule. The Nixon administration viewed this bid as a pivot away from close ties with the United States in favor of continental Europe. After Britain's admission to the EEC in 1973, Heath confirmed this interpretation by notifying his American counterparts that the United Kingdom would henceforth be formulating European policies with other EEC members before discussing them with the United States. Furthermore, Heath indicated his potential willingness to consider a nuclear partnership with France and questioned what the United Kingdom got in return for American use of British military and intelligence facilities worldwide.[91] In return, Nixon and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger briefly cut off the Anglo-American intelligence tap in August 1973.[92] Kissinger then attempted to restore American influence in Europe with his abortive 1973 "Year of Europe" policy plan to update the NATO agreements. Members of the Heath administration, including Heath himself in later years, regarded this announcement with derision.[93]

In 1973, American and British officials disagreed in their handling of the Arab-Israeli Yom Kippur War. While the Nixon administration immediately increased military aid to Israel, Heath maintained British neutrality in the conflict and imposed a British arms embargo on all combatants, which mostly hindered the Israelis by preventing them obtaining spares for their Centurion tanks. Anglo-American disagreement intensified over Nixon's unilateral decision to elevate American forces, stationed at British bases, to DEFCON 3 status on October 25 in response to the breakdown of the United Nations ceasefire.[94] Heath disallowed American intelligence gathering, resupplying, or refueling from British bases in Cyprus, which greatly limited the effective range of American reconnaissance planes.[95] In return, Kissinger imposed a second intelligence cutoff over this disagreement and some in the administration even suggested that the United States should refuse to assist in the British missile upgrade to the Polaris system.[96] Tensions between the United States and United Kingdom relaxed as the second ceasefire took effect. Wilson's return to power in 1974 helped to return Anglo-American relations to normality.

On July 23, 1977, officials from the United Kingdom and the United States renegotiated the previous Bermuda I Agreement, and signed the Bermuda II Agreement under which only four airlines, two from the United Kingdom and two from the United States, were allowed to operate flights between London Heathrow Airport and specified "gateway cities" in the United States. The Bermuda II Agreement was in effect for nearly 30 years until it was eventually replaced by the EU-US Open Skies Agreement, which was signed on April 30, 2007 and entered into effect on March 30, 2008.

Throughout the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher was strongly supportive of Ronald Reagan's unwavering stance towards the Soviet Union. Often described as "political soulmates" and a high point in the "Special Relationship", Reagan and Thatcher met many times throughout their political careers, speaking in concert when confronting Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev.

In 1982, the British Government made a request to the United States, which the Americans agreed upon in principle, to sell the Trident II D5 ballistic missile, associated equipment, and related system support for use on four Vanguard class nuclear submarines in the Royal Navy. The Trident II D5 ballistic missile replaced the United Kingdom's previous use of the UGM-27 Polaris ballistic missile, beginning in the mid-1990s.[86]

In the Falklands War in 1982, the United States initially tried to mediate between the United Kingdom and Argentina, but ended up supporting the United Kingdom's counter-invasion. The United States Defense Department, under Caspar Weinberger, supplied the British military with equipment as well as logistical support.[97]

In October 1983, the United States and a coalition of Caribbean nations undertook Operation Urgent Fury, codename for the invasion of the Commonwealth to the island nation of Grenada. A bloody Marxist coup had overrun Grenada, and neighboring countries in the region asked the United States to intervene militarily, which it did successfully despite having made assurances to a deeply resentful British Government.

On April 15, 1986, the United States Air Force with elements of naval and marine forces launched Operation El Dorado Canyon from RAF Fairford, RAF Upper Heyford, RAF Lakenheath, and RAF Mildenhall in England. Despite firm opposition from within the Conservative Party, Margaret Thatcher allowed Ronald Reagan to use Royal Air Force stations in the United Kingdom during the bombings of Tripoli and Benghazi in Libya, a counter-attack by the United States in response to Muammar Gaddafi's export of state-sponsored terrorism directed towards civilians and American servicemen stationed in West Berlin.

On December 21, 1988, Pan American Worldways' Flight 103 from London Heathrow Airport to New York's John F. Kennedy International Airport exploded over the town of Lockerbie, Scotland, killing 169 Americans and 40 Britons on board. The motive that is generally attributed to Libya can be traced back to a series of military confrontations with the United States Navy in the 1980s in the Gulf of Sidra, the whole of which Libya claimed as its territorial waters. Despite a guilty verdict on January 31, 2001 by the Scottish High Court of Justiciary which ruled against Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, the bomber, on charges of murder and conspiracy to commit murder, Libya never formally admitted carrying out the 1988 bombing over Scotland until 2003.

During the Soviet war in Afghanistan, the United States and the United Kingdom throughout the 1980s provided arms to the Mujahideen rebels in Afghanistan until the last troops from the Soviet Union left Afghanistan on February 15, 1989.

Post-Cold War

When the United States became the world's lone superpower after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, new threats emerged which confronted the United States and its NATO allies. With military build-up beginning in August 1990 and the use of force beginning in January 1991, the United States, followed at a distance by Britain, provided the two largest forces respectively for the coalition army which liberated Kuwait from Saddam Hussein's regime during the Persian Gulf War.

In 1997, the British Labour Party was elected to office for the first time in eighteen years. The new prime minister, Tony Blair, and Bill Clinton both used the expression "Third Way" to describe their centre-left ideologies. In August 1997, the American people expressed solidarity with the British people, sharing in their grief and sense of shock on the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, who perished in a car crash in Paris, France.

Throughout 1998 and 1999, the United States and Britain sent troops to impose peace during the Kosovo War.

War on Terror and Iraq War

.jpg)

67 Britons were among the 2,977 victims killed during the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City, the Pentagon in Arlington County, Virginia, and in an open field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, on September 11, 2001, which were orchestrated by Al-Qaeda. Following the September 11, 2001 attacks, there was an enormous outpouring of sympathy from the United Kingdom for the American people, and Tony Blair was one of George W. Bush's strongest international supporters for bringing al-Qaeda and the Taliban to justice. Indeed, Blair became the most articulate spokesman. He was the only foreign leader to attend an emergency joint session of Congress called immediately after the attacks (and remains the only foreign leader ever to attend such a session), where he received two standing ovations from members of Congress.

The United States declared a War on Terror following the attacks. British forces participated in NATO's war in Afghanistan. Blair took the lead (against the opposition of France, Canada, Germany, China, and Russia) in advocating the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Again Britain was second only to the US in sending forces to Iraq. Both sides wound down after 2009, and withdrew their last troops in 2011. President Bush and Prime Minister Blair provided sustained mutual political and diplomatic support and won votes in Congress and parliament against their critics at home.[98]

The July 7, 2005 London bombings emphasized the difference in the nature of the terrorist threat to both nations. The United States concentrated primarily on global enemies, like the al-Qaeda network and other Islamic extremists from the Middle East. The London bombings were carried out by homegrown extremist Muslims, and it emphasized the United Kingdom's threat from the radicalization of its own people.

By 2007, support amongst the British public for the Iraq war had plummeted.[99] Despite Tony Blair's historically low approval ratings with the British people, mainly due to allegations of faulty government intelligence of Iraq possessing weapons of mass destruction, his unapologetic and unwavering stance for the British alliance with the United States can be summed up in his own words. He said, "We should remain the closest ally of the US ... not because they are powerful, but because we share their values."[100] The alliance between George W. Bush and Tony Blair seriously damaged the prime minister's standing in the eyes of many British citizens.[101] Tony Blair argued it was in the United Kingdom's interest to "protect and strengthen the bond" with the United States regardless of who is in the White House.[102] A perception that the relationship was unequal led to use of the term"Poodle-ism" in the British media, that Britain and its leaders were lapdogs to the Americans.[103]

All British servicemen were withdrawn with the exception of 400 who remained in Iraq until July 31, 2009.[104]

On June 11, 2009, the British Overseas Territory of Bermuda accepted four Chinese Uighurs from the United States' detainment facility known as Guantanamo Bay detention camp located on the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba. At the request of the United States Government, Bermudan officials agreed to host Khaleel Mamut, Hozaifa Parhat, Salahidin Abdulahat, and Abdullah Abdulqadirakhun as guest workers in Bermuda who seven years ago, were all captured by Pakistani bounty hunters during the United States-led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001. This decision agreed upon by American and Bermudan officials drew considerable consternation and contempt by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office as it was viewed by British officials in London that they should have been consulted on whether or not the decision to take in four Chinese Uighurs was a security and foreign issue of which the Bermudian government does not have delegated responsibility over.[105]

Release of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi

On August 20, 2009, The Scottish government headed by Alex Salmond announced that it would release Abdelbaset al-Megrahi on medical grounds. He was the only person convicted of the terrorist plot which killed 169 Americans and 40 Britons on Pan American Worldways' Flight 103 over the town of Lockerbie, Scotland on December 21, 1988. He was sentenced to life in prison in 2001, but was released after being diagnosed with terminal cancer, with around three months to live. Americans said the decision was uncompassionate and insensitive to the memory of the victims of the 1988 Lockerbie bombing. President Barack Obama said that the decision was "highly objectionable."[106] U.S. Ambassador Louis Susman said that although the decision made by Scotland to release Abdelbaset al-Megrahi was seen by the United States as extremely regrettable, relations with the United Kingdom would remain fully intact and strong.[107] The British government led by Gordon Brown was not involved in the release and Gordon Brown stated at a press conference that they had played 'no role' in the decision.[108] Abdelbaset al-Megrahi died May 20, 2012 at the age of 60.

Deepwater Horizon oil spill

In April 2010, the explosion, sinking and resultant oil spill from the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig led to diplomatic friction and populist anti-British sentiment, even though the rig was owned and operated by the Swiss company Transocean and the cement work carried out by the US company Halliburton . Commentators referred to "British Petroleum" even though the company had been known as "BP" since 1998.[109][110] UK politicians expressed concerns about anti-British rhetoric in the US.[111][112] BP's CEO Tony Hayward was called "the most hated man in America".[113] Conversely, the widespread public demonisation of BP and the effects on the company and its image, coupled with Obama's statements with regard to BP caused a degree of anti-American sentiment in the UK. This was particularly evidenced by the comments of the Business Secretary Vince Cable, who said that "It's clear that some of the rhetoric in the US is extreme and unhelpful",[114] for reasons of British pension funds, loss of revenues for the exchequer and the adverse effect such the rhetoric was having on the share price of one of the UK's largest companies. The meeting between Barack Obama and David Cameron in July somewhat helped strained diplomatic relations, and President Obama stated that there lies a "truly special relations" between the two countries. The degree to which anti-British or anti-American hostilities continue to exist, remains to be seen.

Present status

Present British policy is that the relationship with the United States represents the United Kingdom's "most important bilateral relationship" in the world.[4] United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton paid tribute to the relationship in February 2009 by saying, "it stands the test of time".[115]

On March 3, 2009, Gordon Brown made his first visit to the Obama White House. During his visit, he presented the president a gift in the form of a pen holder carved from HMS Gannet, which served anti-slavery missions off the coast of Africa. Barack Obama's gift to the prime minister was a box of 25 DVDs with movies including Star Wars and E.T. The wife of the prime minister, Sarah Brown, gave the Obama daughters, Sasha and Malia, two dresses from British clothing retailer Topshop, and a few unpublished books that have not reached the United States. Michelle Obama gave the prime minister's sons two Marine One helicopter toys.[116] During this visit to the United States, Gordon Brown made an address to a joint session of the United States Congress, a privilege rarely accorded to foreign heads of government.

In March 2009, a Gallup poll of Americans showed 36% identified Britain as their country's "most valuable ally", followed by Canada, Japan, Israel, and Germany rounding out the top five.[117] The poll also indicated that 89% of Americans view the United Kingdom favorably, second only to Canada with 90%.[117] According to the Pew Research Center, a global survey conducted in July 2009 revealed that 70% of Britons who responded had a favorable view of the United States.[118]

In February 2011, The Daily Telegraph, based on evidence from Wikileaks, reported that the United States had tendered sensitive information about the British Trident nuclear arsenal (whose missile delivery systems are manufactured and maintained in the United States) to the Russian Federation as part of a deal to encourage Russia to ratify the New START Treaty. Professor Malcolm Chalmers of the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies speculated that serial numbers could undermine Britain's non-verification policy by providing Russia "with another data point to gauge the size of the British arsenal".[119]

On May 25, 2011, during his official visit to the UK, President Barack Obama reaffirmed the relationship between the United Kingdom and the United States of America in an address to Parliament at Westminster Hall. Amongst other points, Obama stated: "I've come here today to reaffirm one of the oldest; one of the strongest alliances the World has ever known. It's long been said that the United States and The United Kingdom share a special relationship."[120]

In the final days before the Scottish independence referendum in September 2014, President Barack Obama announced in public the vested interest of the United States of America in enjoying the continued partnership with a 'strong and united' UK which he described as "one of the closest allies we will ever have."[121]

Trade, investment and the economy

The United States accounts for the United Kingdom's largest single export market, buying $57 billion worth of British goods in 2007.[122] Total trade of imports and exports between the United Kingdom and the United States amounted to the sum of $107.2 billion in 2007.[123]

The United States and the United Kingdom share the world's largest foreign direct investment partnership. In 2005, American direct investment in the United Kingdom totaled $324 billion while British direct investment in the United States totaled $282 billion.[124]

In a press conference that made several references to the special relationship, US Secretary of State John Kerry, in London with UK Foreign Secretary William Hague on 9 September 2013, said

"We are not only each other's largest investors in each of our countries, one to the other, but the fact is that every day almost one million people go to work in America for British companies that are in the United States, just as more than one million people go to work here in Great Britain for American companies that are here. So we are enormously tied together, obviously. And we are committed to making both the U.S.-UK and the U.S.-EU relationships even stronger drivers of our prosperity."[125]

Tourism

More than 4.5 million Britons visit the United States every year, spending approximately $14 billion. Around 3 million Americans visit the United Kingdom every year, spending approximately $10 billion.[126]

Transportation

New York's John F. Kennedy International Airport is the most popular international destination for people flying out of London Heathrow Airport. Approximately 2,802,870 people on multiple daily non-stop flights flew from Heathrow to JFK in 2008.[127] Concorde, British Airway's flagship supersonic airliner, began trans-Atlantic service to Washington Dulles International Airport in the United States on May 24, 1976. The trans-Atlantic route between London's Heathrow and New York's JFK in under 3½ hours, had its first operational flight between the two hubs on October 19, 1977 and the last being on October 23, 2003.[128]

Cunard Line, a British shipping company which is owned jointly by a British-American-Panamanian parent company, Carnival Corporation, provides seasonal trans-Atlantic crossings aboard the RMS Queen Mary 2 and the MS Queen Victoria between Southampton and New York City.[129]

State and official visits

Reciprocal state and official visits have been made over the years by four Presidents of the United States as well as two British monarchs. Throughout her lifetime, Queen Elizabeth II has met a total of eleven presidents (Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, Bush Sr., Clinton, Bush Jr, and Obama), with the notable exception of Lyndon B. Johnson. She also met ex-President Herbert Hoover in 1957.[130] In addition, the Queen made three private visits in 1984, 1985, and 1991 to see stallion stations and stud farms in the US state of Kentucky.[131]

| Dates | Monarch and Consort | Locations | Itinerary |

| June 7–11, 1939 | King George VI and Queen Elizabeth | Washington D.C., New York City, and Hyde Park (New York) | Paid a state visit to Washington D.C., stayed at the White House, laid a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknowns in Arlington National Cemetery, visited George Washington's Virginian plantation Mount Vernon, made an appearance at the 1939 World's Fair in New York City, and made a private visit to Franklin Roosevelt's upstate New York retreat, Springwood Estate. |

| October 17–20, 1957 | Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh | Jamestown and Williamsburg (Virginia), Washington D.C., and New York City | Paid a state visit to Washington D.C., attended the official ceremonies of the 350th anniversary of the settlement of Jamestown, Virginia, and made a brief stop-over in New York City to address the United Nations General Assembly before sailing to the United Kingdom. |

| July 6–9, 1976 | Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip | Philadelphia, Washington D.C., New York City, Charlottesville (Virginia), Newport and Providence (Rhode Island), and Boston | Paid a state visit to Washington D.C. and toured the United States East Coast in conjunction with the United States Bicentennial celebrations aboard HMY Britannia. |

| February 26 – March 7, 1983 | Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip | San Diego, Palm Springs, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, San Francisco, Yosemite National Park (California), and Seattle (Washington) | Made an official visit to the United States, toured the United States West Coast aboard HMY Britannia, and made a private visit to Ronald Reagan's retreat in the Santa Ynez Mountains, Rancho del Cielo. |

| May 14–17, 1991 | Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip | Washington D.C., Baltimore (Maryland), Miami and Tampa (Florida), Austin, San Antonio, and Houston (Texas), and Lexington (Kentucky) | Paid a state visit to Washington D.C., addressed a joint session of the United States Congress, made a private visit to Kentucky, and toured the Southern United States. |

| May 3–8, 2007 | Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip | Richmond, Jamestown, and Williamsburg (Virginia), Louisville (Kentucky), Greenbelt (Maryland), and Washington D.C. | Paid a state visit to Washington D.C., addressed the Virginia General Assembly, attended the official ceremonies of the 400th anniversary of the establishment of Jamestown, toured NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, visited the National World War II Memorial on the National Mall, and made a private visit to Kentucky to attend the 133rd Kentucky Derby. |

| July 6, 2010 | Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip | New York City | Made a one-day official visit to the United States to address the United Nations General Assembly, visited the World Trade Center site to pay respects to the victims of the September 11 attacks, and paid homage to British victims of the terrorist attack at the Queen Elizabeth II September 11th Garden in Hanover Square. |

| Dates | Administration | Locations | Itinerary |

| December 26–28, 1918 | Woodrow Wilson and Edith Wilson | London, Carlisle, and Manchester | Made an official visit to the United Kingdom, stayed at Buckingham Palace, attended an official dinner, had an audience with King George V and Queen Mary, and made a private visit called the 'pilgrimage of the heart' to the ancestral home of his British-born mother, Janet Woodrow. |

| June 7–9, 1982 | Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan | London and Windsor | Made an official visit to the United Kingdom, stayed at Windsor Castle, attended a state banquet, and addressed the Parliament of the United Kingdom. |

| November 28–December 1, 1995 | Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton | London, Belfast, and Londonderry | Paid a state visit to the United Kingdom and addressed the Parliament of the United Kingdom. |

| November 18–21, 2003 | George W. Bush and Laura Bush | London and Sedgefield | Paid a state visit to the United Kingdom, stayed at Buckingham Palace, attended a state banquet, laid a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey, and made a private visit to Tony Blair's constituency in County Durham, North East England. |

| May 24–26, 2011 | Barack Obama and Michelle Obama | London | Paid a state visit to the United Kingdom, stayed at Buckingham Palace, welcomed during an arrival ceremony in Buckingham Palace Gardens, dined at a state banquet, addressed Parliament in Westminster Hall, presented wedding gifts to Prince William, Duke of Cambridge and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge (donation of MacBook notebook computers to Peace Players International); met with Queen Elizabeth II, Prince Philip, and Prime Minister David Cameron. |

Diplomacy

|

|

Common memberships

Strategic Alliance Cyber Crime Working Group

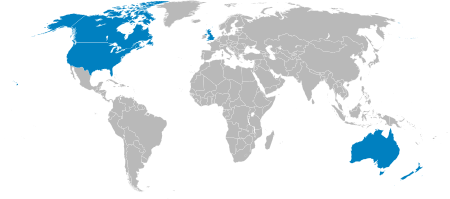

| UKUSA Community |

|---|

|

The Strategic Alliance Cyber Crime Working Group is an initiative by Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and headed by the United States as a "formal partnership between these nations dedicated to tackling larger global crime issues, particularly organized crime." The cooperation consists of "five countries from three continents banding together to fight cyber crime in a synergistic way by sharing intelligence, swapping tools and best practices, and strengthening and even synchronizing their respective laws."[138]

Within this initiative, there is increased information sharing between the United Kingdom's Serious Organised Crime Agency and the United States' Federal Bureau of Investigation on matters relating to serious fraud or cyber crime.

UK-USA Security Agreement

The UK-USA Security Agreement is an alliance of five English-speaking countries; Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States, for the sole purpose of sharing intelligence. The precursor to this agreement is essentially an extension of the historic BRUSA Agreement which was signed in 1943. In association with the ECHELON system, all five nations are assigned to intelligence collection and analysis from different parts of the world. For example, the United Kingdom hunts for communications in Europe, Africa, and Russia west of the Ural Mountains whereas the United States has responsibility for gathering intelligence in Latin America, Asia, Asiatic Russia, and northern mainland China.[139]

Sister-Twinning cities

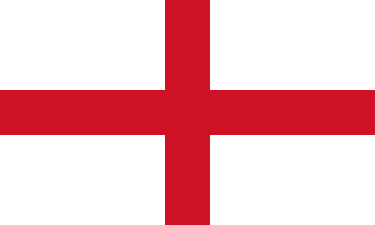

England and the United States

Scotland and the United States

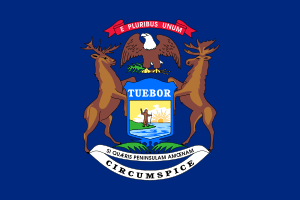

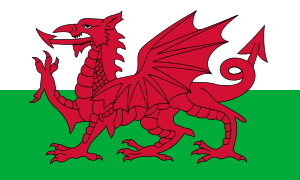

Wales and the United States

-

Brecon and

Brecon and  Saline, Michigan

Saline, Michigan -

Machynlleth and

Machynlleth and  Belleville, Michigan

Belleville, Michigan -

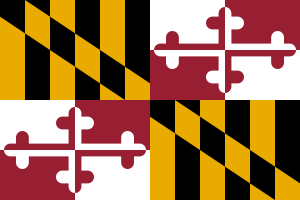

Newport, Pembrokeshire, and

Newport, Pembrokeshire, and  Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis, Maryland

Northern Ireland and the United States

Friendship links

-

Liverpool and

Liverpool and  Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis, Tennessee -

Liverpool and

Liverpool and  New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans, Louisiana -

Newcastle upon Tyne and

Newcastle upon Tyne and  Little Rock, Arkansas

Little Rock, Arkansas -

Wellingborough and

Wellingborough and  Willingboro, New Jersey

Willingboro, New Jersey

Heritage

The United States and Britain share many threads of cultural heritage.

Since English is the main language of both the British and the Americans, both nations belong to the English-speaking world. Their common language comes with (relatively minor) differences in spelling, pronunciation, and the meaning of words.[140]

The American legal system is largely based on English common law. The American system of local government is rooted in English precedents, such as the offices of county courts and sheriffs. Although the US, unlike Britain, remains highly religious,[141] the largest Protestant denominations emerged from British churches brought across the Atlantic, such as the Baptists, Methodists, Congregationalists and Episcopalians.

Britain and the United States practise what is commonly referred to as an Anglo-Saxon economy in which levels of regulation and taxes are relatively low, and government provides a low to medium level of social services in return.[142]

Independence Day, July 4, is a national celebration which commemorates the July 4, 1776 adoption of the Declaration of Independence from the British Empire. American defiance of Britain is expressed in the American national anthem, The Star Spangled Banner, written during the War of 1812 to the tune of a British celebratory song as the Americans beat off a British attack on Baltimore.

It is estimated that between 40.2 million and 72.1 million Americans today have British ancestry, i.e. between 13% and 23.3% of the US population.[143][144][145] In the 1980 US Census, 61,311,449 Americans reported British ancestry reaching 32.56% of the US population at the time which, even today, would make them the largest ancestry group in the United States.[146]

Particular symbols of the close relationship between the two countries are the JFK Memorial and the American Bar Association's Magna Carta Memorial, both at Runnymede in England.

Popular culture

Literature

Literature is transferred across the Atlantic Ocean, as evidenced by the appeal of British authors such as William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, J. R. R. Tolkien, Jackie Collins, and J. K. Rowling in the United States, and American authors such as Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mark Twain, Ernest Hemingway, Stephen King and Dan Brown in Britain. Henry James moved to Britain and was well known in both countries, as was T. S. Eliot. Eliot moved to England in 1914 and became a British subject in 1927. He was a dominant figure in literary criticism and greatly influenced the Modern period of British literature.[147]

Print journalism

British Sunday broadsheet newspaper The Observer includes a condensed copy of The New York Times.[148]

Film

There is much crossover appeal in the modern entertainment culture of the United Kingdom and the United States. For example, Hollywood blockbuster movies made by Steven Spielberg and George Lucas have had a large effect on British audiences in the United Kingdom, while the James Bond and Harry Potter series of films have attracted high interest in the United States. Also, the animated films of Walt Disney as well as those of Pixar, DreamWorks, Don Bluth, Blue Sky, Illumination and others have continued to make an indelible mark and impression on British audiences, young and old, for almost 100 years. Films by Alfred Hitchcock continuously make a lasting impact on a loyal fan base in the United States, as Alfred Hitchcock himself influenced notable American film makers such as John Carpenter, in the horror and slasher film genres.

Production of films are often shared between the two nations, whether it be a concentrated use of British and American actors or the use of film studios located in London or Hollywood.

Theatre